The Negro’s Complaint: A Poem. To Which Is Added, Pity for Poor Africans

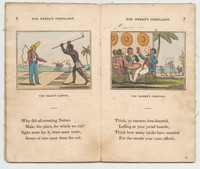

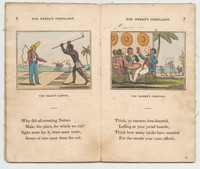

The Negro’s Complaint: A Poem. To Which Is Added, Pity for Poor Africans During the initial rise of the sugar boycotts in Britain, Cooper’s two poems were first printed and widely distributed in 1788 by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. They are not production stories. Nevertheless, this reprint edition by children’s publishers Harvey and Darton uses popular generic conventions for teaching children about commodities. “The Negro’s Complaint” uses the same visual layout as contemporaneous production stories by Opie and Wallis, with a titled illustration and poetry stanzas underneath. One spread shows enslaved Africans planting sugar cane in square holes (p. 6), an illustration nearly identical to those of other sugar production stories (e.g. William Newman, A history of a Pound of Sugar, p. 3). Drawing further parallels, Harvey and Darton used the same illustrator as Amelia Alderson Opie’s The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar, a sugar production story they published the same year.

Because of these editorial choices, Cooper’s poem takes on a new meaning for readers familiar with the production story form. Harvey and Darton draw comparisons between production stories and slave autobiographies, two forms that share narrative similarities. The titles of production stories (e.g. The Progress of Cotton; The Story of Sugar) make a commodity into a protagonist (e.g. sugar, cotton, coal), as if children are reading the commodity’s autobiography, and in fact, some fantastical production stories have commodities that come to life and speak their own life histories to human audiences. Autobiographies of former slaves, on the other hand, feature protagonists who were dehumanized as commodities for trade. When Cooper’s narrator, a fictional enslaved African, tells his own story, he follows in this tradition of abolitionist autobiographies. With their editorial choices, Harvey and Darton question why some production stories give agency to personified commodities while dehumanizing the enslaved persons forced to make them.

Readers familiar with production story conventions would recognize other places where this book plays with the form. The illustration titled “The Master’s Carousal” positions a standard illustration for the cane harvest in the background, in order to focus, instead, on the “jovial” masters drinking and smoking in the foreground. Readers must confront the “iron-hearted” white men, who drink rum and smoke tobacco, and feel shame that they, too, have enjoyed commodities made by enslaved persons.

The second poem in the collection, “Pity for Poor Africans,” has no illustrations, but its effect relies on familiarity with another popular children’s literature genre: the moral tale. The narrator is an Englishman who justifies eating sugar because a boycott would be ineffective, since others eat sugar anyway. He compares his choice to a boy who steals apples from an orchard, after he fails to convince his friends to abstain. Readers familiar with moral tales that warn boys not to steal apples would immediate recognize the speaker’s sophistry, then reevaluate their own choices on sugar consumption. The selection of both poems together suggests that Harvey and Darton considered how to frame abolitionist messages to speak to children, using literary conventions familiar to them.

The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar

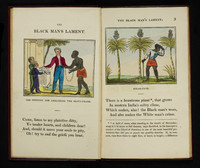

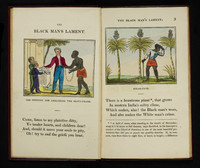

The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar One of the earliest abolitionist books for children, this production story by the Quaker abolitionist novelist and poet, Amelia Alderson Opie is a call to political action that eschews the pleasures of consumption. The copperplate engravings are by an unknown artist, but the style indicates that children’s publishers Harvey and Darton, a prominent abolitionist and Quaker firm, used the same artist for their reprint of William Cowper’s “The Negro’s Complaint” (Cutter, p. 71). According to historian Martha Cutter, the illustrator takes care to represent “distinctive (rather than stereotypical) persons,” who allow for intersubjectivity by meeting the viewer’s gaze (p. 82).

Opie adapts the production story formula to foreground her abolitionist message, by opening her story with a plea to readers “to end the griefs you hear (p.2). The opening illustration shows two children signing a petition in support of abolition of the slave trade. A man in chains on the right resembles Wedgewood’s often circulated abolitionist image of a supplicant slave, but rather than kneeling, he stands and reaches out to the children. The right-hand page introduces sugar cane as a “beauteous plant” that “makes, alas! The Blank man’s woes, / And also makes the White man’s crimes,” with a lengthy small print footnote on sugar cane’s appearance and cultivation (p. 3). Readers accustomed to the scientific language of production stories would be surprised to find the actual process of sugar making relegated to the footnotes. Again, on the next spread, technical detail that would usually occupy a prominent place remains peripheral, while the emotional appeal of a human story dominates (p. 4). At this moment in the story, the enslaved man takes over narration until its conclusion. The accompanying illustration shows him “torn” from his wife and infant by men wielding swords and cudgels (p. 5).

Some of the images, such as “Cutting Down the Sugar-Cane” and “The Bruising-Mill” (pp. 16-17) closely resemble those provided in other sugar production narratives, such as Negro Labour (1809) or William Newman’s A History of a Pound of Sugar (1861). This conformity to generic expectations makes the unique text below the images all the more striking. Harvest time is usually portrayed in sugar production narratives as a joyous, healthful time when harvesters gain weight by chewing the ends of cut cane. But in a departure from this formula, Opie’s speaker describes harvest as the beginning of “our saddest pains; / For then we toil both day and night.” Instead of feeding themselves, they feed an ever-hungry grinding mill.

The Negro’s Complaint: A Poem. To Which Is Added, Pity for Poor Africans During the initial rise of the sugar boycotts in Britain, Cooper’s two poems were first printed and widely distributed in 1788 by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. They are not production stories. Nevertheless, this reprint edition by children’s publishers Harvey and Darton uses popular generic conventions for teaching children about commodities. “The Negro’s Complaint” uses the same visual layout as contemporaneous production stories by Opie and Wallis, with a titled illustration and poetry stanzas underneath. One spread shows enslaved Africans planting sugar cane in square holes (p. 6), an illustration nearly identical to those of other sugar production stories (e.g. William Newman, A history of a Pound of Sugar, p. 3). Drawing further parallels, Harvey and Darton used the same illustrator as Amelia Alderson Opie’s The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar, a sugar production story they published the same year. Because of these editorial choices, Cooper’s poem takes on a new meaning for readers familiar with the production story form. Harvey and Darton draw comparisons between production stories and slave autobiographies, two forms that share narrative similarities. The titles of production stories (e.g. The Progress of Cotton; The Story of Sugar) make a commodity into a protagonist (e.g. sugar, cotton, coal), as if children are reading the commodity’s autobiography, and in fact, some fantastical production stories have commodities that come to life and speak their own life histories to human audiences. Autobiographies of former slaves, on the other hand, feature protagonists who were dehumanized as commodities for trade. When Cooper’s narrator, a fictional enslaved African, tells his own story, he follows in this tradition of abolitionist autobiographies. With their editorial choices, Harvey and Darton question why some production stories give agency to personified commodities while dehumanizing the enslaved persons forced to make them. Readers familiar with production story conventions would recognize other places where this book plays with the form. The illustration titled “The Master’s Carousal” positions a standard illustration for the cane harvest in the background, in order to focus, instead, on the “jovial” masters drinking and smoking in the foreground. Readers must confront the “iron-hearted” white men, who drink rum and smoke tobacco, and feel shame that they, too, have enjoyed commodities made by enslaved persons. The second poem in the collection, “Pity for Poor Africans,” has no illustrations, but its effect relies on familiarity with another popular children’s literature genre: the moral tale. The narrator is an Englishman who justifies eating sugar because a boycott would be ineffective, since others eat sugar anyway. He compares his choice to a boy who steals apples from an orchard, after he fails to convince his friends to abstain. Readers familiar with moral tales that warn boys not to steal apples would immediate recognize the speaker’s sophistry, then reevaluate their own choices on sugar consumption. The selection of both poems together suggests that Harvey and Darton considered how to frame abolitionist messages to speak to children, using literary conventions familiar to them.

The Negro’s Complaint: A Poem. To Which Is Added, Pity for Poor Africans During the initial rise of the sugar boycotts in Britain, Cooper’s two poems were first printed and widely distributed in 1788 by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. They are not production stories. Nevertheless, this reprint edition by children’s publishers Harvey and Darton uses popular generic conventions for teaching children about commodities. “The Negro’s Complaint” uses the same visual layout as contemporaneous production stories by Opie and Wallis, with a titled illustration and poetry stanzas underneath. One spread shows enslaved Africans planting sugar cane in square holes (p. 6), an illustration nearly identical to those of other sugar production stories (e.g. William Newman, A history of a Pound of Sugar, p. 3). Drawing further parallels, Harvey and Darton used the same illustrator as Amelia Alderson Opie’s The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar, a sugar production story they published the same year. Because of these editorial choices, Cooper’s poem takes on a new meaning for readers familiar with the production story form. Harvey and Darton draw comparisons between production stories and slave autobiographies, two forms that share narrative similarities. The titles of production stories (e.g. The Progress of Cotton; The Story of Sugar) make a commodity into a protagonist (e.g. sugar, cotton, coal), as if children are reading the commodity’s autobiography, and in fact, some fantastical production stories have commodities that come to life and speak their own life histories to human audiences. Autobiographies of former slaves, on the other hand, feature protagonists who were dehumanized as commodities for trade. When Cooper’s narrator, a fictional enslaved African, tells his own story, he follows in this tradition of abolitionist autobiographies. With their editorial choices, Harvey and Darton question why some production stories give agency to personified commodities while dehumanizing the enslaved persons forced to make them. Readers familiar with production story conventions would recognize other places where this book plays with the form. The illustration titled “The Master’s Carousal” positions a standard illustration for the cane harvest in the background, in order to focus, instead, on the “jovial” masters drinking and smoking in the foreground. Readers must confront the “iron-hearted” white men, who drink rum and smoke tobacco, and feel shame that they, too, have enjoyed commodities made by enslaved persons. The second poem in the collection, “Pity for Poor Africans,” has no illustrations, but its effect relies on familiarity with another popular children’s literature genre: the moral tale. The narrator is an Englishman who justifies eating sugar because a boycott would be ineffective, since others eat sugar anyway. He compares his choice to a boy who steals apples from an orchard, after he fails to convince his friends to abstain. Readers familiar with moral tales that warn boys not to steal apples would immediate recognize the speaker’s sophistry, then reevaluate their own choices on sugar consumption. The selection of both poems together suggests that Harvey and Darton considered how to frame abolitionist messages to speak to children, using literary conventions familiar to them. The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar One of the earliest abolitionist books for children, this production story by the Quaker abolitionist novelist and poet, Amelia Alderson Opie is a call to political action that eschews the pleasures of consumption. The copperplate engravings are by an unknown artist, but the style indicates that children’s publishers Harvey and Darton, a prominent abolitionist and Quaker firm, used the same artist for their reprint of William Cowper’s “The Negro’s Complaint” (Cutter, p. 71). According to historian Martha Cutter, the illustrator takes care to represent “distinctive (rather than stereotypical) persons,” who allow for intersubjectivity by meeting the viewer’s gaze (p. 82). Opie adapts the production story formula to foreground her abolitionist message, by opening her story with a plea to readers “to end the griefs you hear (p.2). The opening illustration shows two children signing a petition in support of abolition of the slave trade. A man in chains on the right resembles Wedgewood’s often circulated abolitionist image of a supplicant slave, but rather than kneeling, he stands and reaches out to the children. The right-hand page introduces sugar cane as a “beauteous plant” that “makes, alas! The Blank man’s woes, / And also makes the White man’s crimes,” with a lengthy small print footnote on sugar cane’s appearance and cultivation (p. 3). Readers accustomed to the scientific language of production stories would be surprised to find the actual process of sugar making relegated to the footnotes. Again, on the next spread, technical detail that would usually occupy a prominent place remains peripheral, while the emotional appeal of a human story dominates (p. 4). At this moment in the story, the enslaved man takes over narration until its conclusion. The accompanying illustration shows him “torn” from his wife and infant by men wielding swords and cudgels (p. 5). Some of the images, such as “Cutting Down the Sugar-Cane” and “The Bruising-Mill” (pp. 16-17) closely resemble those provided in other sugar production narratives, such as Negro Labour (1809) or William Newman’s A History of a Pound of Sugar (1861). This conformity to generic expectations makes the unique text below the images all the more striking. Harvest time is usually portrayed in sugar production narratives as a joyous, healthful time when harvesters gain weight by chewing the ends of cut cane. But in a departure from this formula, Opie’s speaker describes harvest as the beginning of “our saddest pains; / For then we toil both day and night.” Instead of feeding themselves, they feed an ever-hungry grinding mill.

The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar One of the earliest abolitionist books for children, this production story by the Quaker abolitionist novelist and poet, Amelia Alderson Opie is a call to political action that eschews the pleasures of consumption. The copperplate engravings are by an unknown artist, but the style indicates that children’s publishers Harvey and Darton, a prominent abolitionist and Quaker firm, used the same artist for their reprint of William Cowper’s “The Negro’s Complaint” (Cutter, p. 71). According to historian Martha Cutter, the illustrator takes care to represent “distinctive (rather than stereotypical) persons,” who allow for intersubjectivity by meeting the viewer’s gaze (p. 82). Opie adapts the production story formula to foreground her abolitionist message, by opening her story with a plea to readers “to end the griefs you hear (p.2). The opening illustration shows two children signing a petition in support of abolition of the slave trade. A man in chains on the right resembles Wedgewood’s often circulated abolitionist image of a supplicant slave, but rather than kneeling, he stands and reaches out to the children. The right-hand page introduces sugar cane as a “beauteous plant” that “makes, alas! The Blank man’s woes, / And also makes the White man’s crimes,” with a lengthy small print footnote on sugar cane’s appearance and cultivation (p. 3). Readers accustomed to the scientific language of production stories would be surprised to find the actual process of sugar making relegated to the footnotes. Again, on the next spread, technical detail that would usually occupy a prominent place remains peripheral, while the emotional appeal of a human story dominates (p. 4). At this moment in the story, the enslaved man takes over narration until its conclusion. The accompanying illustration shows him “torn” from his wife and infant by men wielding swords and cudgels (p. 5). Some of the images, such as “Cutting Down the Sugar-Cane” and “The Bruising-Mill” (pp. 16-17) closely resemble those provided in other sugar production narratives, such as Negro Labour (1809) or William Newman’s A History of a Pound of Sugar (1861). This conformity to generic expectations makes the unique text below the images all the more striking. Harvest time is usually portrayed in sugar production narratives as a joyous, healthful time when harvesters gain weight by chewing the ends of cut cane. But in a departure from this formula, Opie’s speaker describes harvest as the beginning of “our saddest pains; / For then we toil both day and night.” Instead of feeding themselves, they feed an ever-hungry grinding mill.