Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar

Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar is one of the earliest sugar production stories created for children. Published two years after the abolition of the slave trade in Britain, the book begins by criticizing slavery but ultimately supports its continuation, “for it is now become the interest of the Planter to take more care of his Slaves, to feed them better, and to work them more moderately than he used to do, since he cannot now supply the places of those who die among them, as he could do before the abolition of that wicked Traffic, by the purchase of a fresh parcel, whenever a Slave-ship brought in a Cargo from Africa” (p. 4). Negro Labour shows how the abolition of the slave trade could be used to justify slavery itself. Contrary to the author’s predictions, ending the slave trade did not end overwork, starvation, and torture on plantations. Instead, selling enslaved children became a larger part of the slave plantation economy.

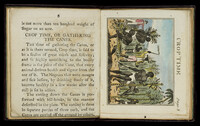

The majority of the text focuses on technical details of sugar production, while avoiding overt acknowledgement of slavery or suggesting any political action on the part of readers. Accompanying illustrations, likely crafted without seeing the text, are often at odds with the apologist tone of the text. The section titled “Crop time, or Gathering the Canes,” for instance, describes the cane harvest as “a season of great mirth and festivity; and so highly nourishing to the bodily frame is the juice of the Cane that every animal derives health and vigour from the use of it. The Negroes that were meagre and sick before, by drinking freely of it, become healthy in a few weeks after the mill is set in action.” The lie that enslaved persons share in the harvest benefits attempts to counter abolitionist accounts of starvation and ignores that enslaved persons worked long hours during harvest and faced dangerous conditions in sugar mills. (A similar depiction of harvest time appears in Cuffy the Negro’s Doggrel Description of the Progress of Sugar.) An accompanying illustration, however, frankly depicts violence. Six black men cut and gather the cane, while two of them look over their shoulder in fear at a black overseer with a whip.

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar Each page of this chapbook features a single illustration depicting one part in the process of making sugar. Readers follow sugar production from slave labor in West Indies plantation cane fields to sugar refineries in British port cities, and finally, to confectioners shops where children purchase sugary treats. John Wallis printed a series of three such production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in contrived dialect and doggerel poetry by the fictional character called Cuffy. Formerly enslaved in the West Indies and recently arrived in London, Cuffy promises to tell audiences what he knows about making these commodities in exchange for coin. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons. Without explicitly supporting slavery, the book effectively defends slavery by depicting work on sugar plantations as so enjoyable that Cuffy regrets leaving. Cane harvesting is a “merry time!” when enslaved persons (denigrated here as livestock) “cut the canes, suck the juice and thrive; / Mule grow fat as hog, though much work he bear-ee; / Horse and cow grow far, starving is no there” (p9). In fact, many enslaved persons starved at harvest time because of the relentless pace of work. The later stages of sugar production in England are shown performed by free white persons. At the conclusion, Cuffy thanks the reader for “kind relief,” or money given to tell his story, directly involving readers in the slave-sugar economy as consumers.

The chapbook is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. Yet the racial context of sugar production makes this process take on metaphorical meanings at every turn. Enslaved Africans created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. Sugar production stories used this language of brown, white, and refined, to continually remind readers of constructed racial hierarchies. Moreover, the process of refining sugar required animal blood, or as Cuffy describes: “To make sugar white (sure he be a ninny!) / Blood, and nasty something, baker now put in-ee” (p.15). Beginning in the 1790s, many abolitionist politicians and poets alluded to this fact to make eating slave sugar disgusting. People should boycott sugar, they argued, because slavery is a cannibalistic institution. Since harvesting cane causes the death of overworked, starved enslaved persons, sugar is essentially refined in human blood (See also Sandiford, 2000, p. 124; Sheller, 2003, pp. 88-97).

This abolitionist interpretation of the material process—what Timothy Morton calls the “blood sugar topos” (1998, p. 88)—was disseminated so widely that Wallis’s readers may recall this message while reading Cuffy’s account. The image of the “Confectioner,” for instance, shows a plump white man boiling a purple-red liquid in a large pan, suspended over an open stove flame. Although the text describes the liquid as “sugar-plum or candy,” the purple-red coloring may remind readers of human blood. Production stories that condone slavery, such as this one, tend to double-down on the literal, material process of refining sugar, as a way to avoid alluding to the blood sugar topos. This strategy is another example of how production stories can use scientific language to try to avoid addressing social conflict.

Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar is one of the earliest sugar production stories created for children. Published two years after the abolition of the slave trade in Britain, the book begins by criticizing slavery but ultimately supports its continuation, “for it is now become the interest of the Planter to take more care of his Slaves, to feed them better, and to work them more moderately than he used to do, since he cannot now supply the places of those who die among them, as he could do before the abolition of that wicked Traffic, by the purchase of a fresh parcel, whenever a Slave-ship brought in a Cargo from Africa” (p. 4). Negro Labour shows how the abolition of the slave trade could be used to justify slavery itself. Contrary to the author’s predictions, ending the slave trade did not end overwork, starvation, and torture on plantations. Instead, selling enslaved children became a larger part of the slave plantation economy. The majority of the text focuses on technical details of sugar production, while avoiding overt acknowledgement of slavery or suggesting any political action on the part of readers. Accompanying illustrations, likely crafted without seeing the text, are often at odds with the apologist tone of the text. The section titled “Crop time, or Gathering the Canes,” for instance, describes the cane harvest as “a season of great mirth and festivity; and so highly nourishing to the bodily frame is the juice of the Cane that every animal derives health and vigour from the use of it. The Negroes that were meagre and sick before, by drinking freely of it, become healthy in a few weeks after the mill is set in action.” The lie that enslaved persons share in the harvest benefits attempts to counter abolitionist accounts of starvation and ignores that enslaved persons worked long hours during harvest and faced dangerous conditions in sugar mills. (A similar depiction of harvest time appears in Cuffy the Negro’s Doggrel Description of the Progress of Sugar.) An accompanying illustration, however, frankly depicts violence. Six black men cut and gather the cane, while two of them look over their shoulder in fear at a black overseer with a whip.

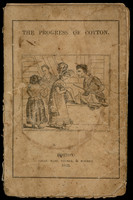

Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar is one of the earliest sugar production stories created for children. Published two years after the abolition of the slave trade in Britain, the book begins by criticizing slavery but ultimately supports its continuation, “for it is now become the interest of the Planter to take more care of his Slaves, to feed them better, and to work them more moderately than he used to do, since he cannot now supply the places of those who die among them, as he could do before the abolition of that wicked Traffic, by the purchase of a fresh parcel, whenever a Slave-ship brought in a Cargo from Africa” (p. 4). Negro Labour shows how the abolition of the slave trade could be used to justify slavery itself. Contrary to the author’s predictions, ending the slave trade did not end overwork, starvation, and torture on plantations. Instead, selling enslaved children became a larger part of the slave plantation economy. The majority of the text focuses on technical details of sugar production, while avoiding overt acknowledgement of slavery or suggesting any political action on the part of readers. Accompanying illustrations, likely crafted without seeing the text, are often at odds with the apologist tone of the text. The section titled “Crop time, or Gathering the Canes,” for instance, describes the cane harvest as “a season of great mirth and festivity; and so highly nourishing to the bodily frame is the juice of the Cane that every animal derives health and vigour from the use of it. The Negroes that were meagre and sick before, by drinking freely of it, become healthy in a few weeks after the mill is set in action.” The lie that enslaved persons share in the harvest benefits attempts to counter abolitionist accounts of starvation and ignores that enslaved persons worked long hours during harvest and faced dangerous conditions in sugar mills. (A similar depiction of harvest time appears in Cuffy the Negro’s Doggrel Description of the Progress of Sugar.) An accompanying illustration, however, frankly depicts violence. Six black men cut and gather the cane, while two of them look over their shoulder in fear at a black overseer with a whip. Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Cotton John Wallis printed three production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in a contrived dialect by the fictional character named Cuffy. Recently arrived in London from the West Indies, Cuffy learned how these commodities are made while enslaved, and he promises to tell audiences what he knows. The frontispiece shows the pleasures of consuming these goods, as ladies select cotton cloth for purchase from a smiling salesperson. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons and encourages consumption of cotton products.

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Cotton John Wallis printed three production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in a contrived dialect by the fictional character named Cuffy. Recently arrived in London from the West Indies, Cuffy learned how these commodities are made while enslaved, and he promises to tell audiences what he knows. The frontispiece shows the pleasures of consuming these goods, as ladies select cotton cloth for purchase from a smiling salesperson. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons and encourages consumption of cotton products. Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar Each page of this chapbook features a single illustration depicting one part in the process of making sugar. Readers follow sugar production from slave labor in West Indies plantation cane fields to sugar refineries in British port cities, and finally, to confectioners shops where children purchase sugary treats. John Wallis printed a series of three such production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in contrived dialect and doggerel poetry by the fictional character called Cuffy. Formerly enslaved in the West Indies and recently arrived in London, Cuffy promises to tell audiences what he knows about making these commodities in exchange for coin. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons. Without explicitly supporting slavery, the book effectively defends slavery by depicting work on sugar plantations as so enjoyable that Cuffy regrets leaving. Cane harvesting is a “merry time!” when enslaved persons (denigrated here as livestock) “cut the canes, suck the juice and thrive; / Mule grow fat as hog, though much work he bear-ee; / Horse and cow grow far, starving is no there” (p9). In fact, many enslaved persons starved at harvest time because of the relentless pace of work. The later stages of sugar production in England are shown performed by free white persons. At the conclusion, Cuffy thanks the reader for “kind relief,” or money given to tell his story, directly involving readers in the slave-sugar economy as consumers. The chapbook is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. Yet the racial context of sugar production makes this process take on metaphorical meanings at every turn. Enslaved Africans created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. Sugar production stories used this language of brown, white, and refined, to continually remind readers of constructed racial hierarchies. Moreover, the process of refining sugar required animal blood, or as Cuffy describes: “To make sugar white (sure he be a ninny!) / Blood, and nasty something, baker now put in-ee” (p.15). Beginning in the 1790s, many abolitionist politicians and poets alluded to this fact to make eating slave sugar disgusting. People should boycott sugar, they argued, because slavery is a cannibalistic institution. Since harvesting cane causes the death of overworked, starved enslaved persons, sugar is essentially refined in human blood (See also Sandiford, 2000, p. 124; Sheller, 2003, pp. 88-97). This abolitionist interpretation of the material process—what Timothy Morton calls the “blood sugar topos” (1998, p. 88)—was disseminated so widely that Wallis’s readers may recall this message while reading Cuffy’s account. The image of the “Confectioner,” for instance, shows a plump white man boiling a purple-red liquid in a large pan, suspended over an open stove flame. Although the text describes the liquid as “sugar-plum or candy,” the purple-red coloring may remind readers of human blood. Production stories that condone slavery, such as this one, tend to double-down on the literal, material process of refining sugar, as a way to avoid alluding to the blood sugar topos. This strategy is another example of how production stories can use scientific language to try to avoid addressing social conflict.

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar Each page of this chapbook features a single illustration depicting one part in the process of making sugar. Readers follow sugar production from slave labor in West Indies plantation cane fields to sugar refineries in British port cities, and finally, to confectioners shops where children purchase sugary treats. John Wallis printed a series of three such production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in contrived dialect and doggerel poetry by the fictional character called Cuffy. Formerly enslaved in the West Indies and recently arrived in London, Cuffy promises to tell audiences what he knows about making these commodities in exchange for coin. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons. Without explicitly supporting slavery, the book effectively defends slavery by depicting work on sugar plantations as so enjoyable that Cuffy regrets leaving. Cane harvesting is a “merry time!” when enslaved persons (denigrated here as livestock) “cut the canes, suck the juice and thrive; / Mule grow fat as hog, though much work he bear-ee; / Horse and cow grow far, starving is no there” (p9). In fact, many enslaved persons starved at harvest time because of the relentless pace of work. The later stages of sugar production in England are shown performed by free white persons. At the conclusion, Cuffy thanks the reader for “kind relief,” or money given to tell his story, directly involving readers in the slave-sugar economy as consumers. The chapbook is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. Yet the racial context of sugar production makes this process take on metaphorical meanings at every turn. Enslaved Africans created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. Sugar production stories used this language of brown, white, and refined, to continually remind readers of constructed racial hierarchies. Moreover, the process of refining sugar required animal blood, or as Cuffy describes: “To make sugar white (sure he be a ninny!) / Blood, and nasty something, baker now put in-ee” (p.15). Beginning in the 1790s, many abolitionist politicians and poets alluded to this fact to make eating slave sugar disgusting. People should boycott sugar, they argued, because slavery is a cannibalistic institution. Since harvesting cane causes the death of overworked, starved enslaved persons, sugar is essentially refined in human blood (See also Sandiford, 2000, p. 124; Sheller, 2003, pp. 88-97). This abolitionist interpretation of the material process—what Timothy Morton calls the “blood sugar topos” (1998, p. 88)—was disseminated so widely that Wallis’s readers may recall this message while reading Cuffy’s account. The image of the “Confectioner,” for instance, shows a plump white man boiling a purple-red liquid in a large pan, suspended over an open stove flame. Although the text describes the liquid as “sugar-plum or candy,” the purple-red coloring may remind readers of human blood. Production stories that condone slavery, such as this one, tend to double-down on the literal, material process of refining sugar, as a way to avoid alluding to the blood sugar topos. This strategy is another example of how production stories can use scientific language to try to avoid addressing social conflict.