The Story of Your Bread

Item- Title

- The Story of Your Bread

- Description

-

Since the nineteenth-century, many production story series have included a volume on bread, a food that holds symbolic significance in Christian cultures that associate “daily bread” with both holy communion and basic sustenance. This second book on bread by Clara Hollos, published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor at Young world Books, follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Hollos humanizes a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Alongside technological inventions, Hollos describes the social context of production, including slavery, serfdom, and hunger. Illustrations by Lászlo Roth change style to reflect that “people all through the centuries had their own ways of drawing and painting,” as well as their own ways of making bread, the “king of foods.”

Unlike her first book on wool coats, The Story of Your Bread offers a global historical survey of bread making, from “the Stone Age to our times,” in which farming and baking are indexes of civilization. This pan-historical approach to production stories takes after some of the earliest production stories. The Arts of Life by John Aiken (1803), for example, argues that technology, cooperation, and government initially arose from the desire to provide for three basic human needs: food, clothing, and shelter. Such production stories recapitulate the story of mankind organized around single commodities (sometimes groups of commodities), creating a progressive history that culminates in the modern, technologically enhanced production of the goods enjoyed by the reader.

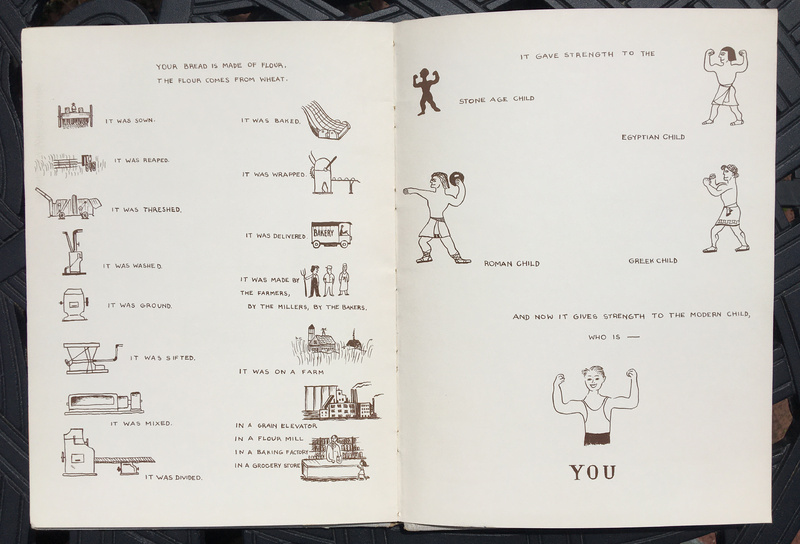

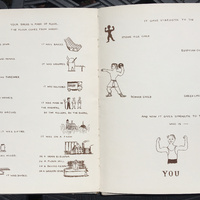

In production stories, this panhistorical approach often naturalizes the economic dominance of Europeans and European Americans. Nowhere is this more clear than in the final spread of The Story of Your Bread. Four human figures represent different phases in history: “Stone age child,” Egyptian child,” “Roman child,” and “Greek child.” Underneath these, the text states, “And now it give strength to the modern child, who is—YOU,” with a picture of a boy flexing his muscles. Although different races and ethnicities appear in Lászlo’s illustrations, history culminates in the strength of this white male child, who represents the book’s reader and bread eater.

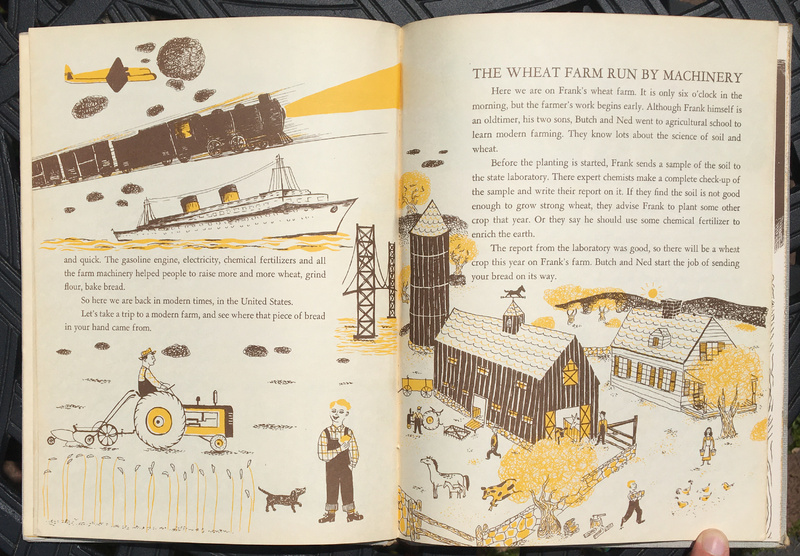

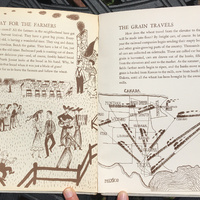

Books for younger readers balance a celebration of modern technology with assurances that things will stay the same. In “The Wheat Farm Run by Machinery,” a family farm relies on tractors and modern chemistry, and the farm is flanked by the transportation network that connects agriculture to the city: planes, trains, steamships, and suspension bridges. The farmer’s sons, Butch and Ned, study chemistry at the university, expertise they apply to test the soil and understand what plants will grow. Yet the emphasis on a generational family unit promises readers that farm life will continue from one generation to the next. New modes of communication and transportation will, the image suggests, actually support cultural continuity for families like this one. Similarly, another image of farming families during the harvest features a nostalgic scene of dancing and feasting, juxtaposed with a roadroad map of the US. Again, the modern family of farmers is predominantly European American, suggesting a racially narrow vision of who uses and prospers from new technologies.

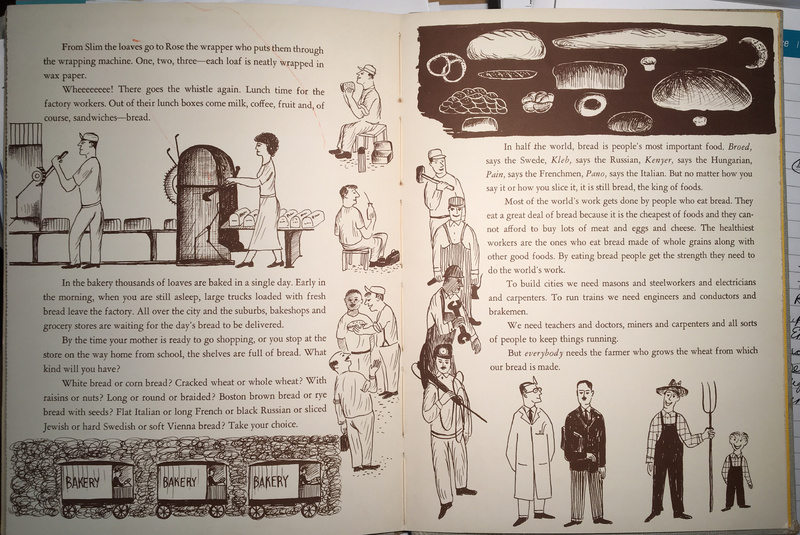

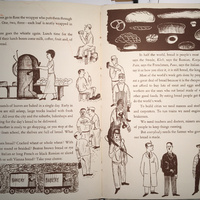

The book is more inclusive where class is concerned. The image of the large factory where people bake bread, for instance, shows workers with distinct faces and appearances, which gives a sense of individuality. The accompanying text describes the many different kinds of bread that bakeries produce for sale at the store and gives words for bread in different languages. Bread is the “king of foods,” not because only kings eat bread, but because everyone eats bread. Bread can feed large populations and keep them strong: “Most of the world’s work gets done by people who eat bread. They eat a great deal of bread because it is the cheapest of foods and they cannot afford to buy lots of meat and eggs and cheese. The healthiest workers are the ones who eat bread made of whole grains along with other good foods. By eating bread people get the strength they need to do the world’s work.” The page concludes by celebrating farmers for their important work, because they grow “the wheat from which our bread is made.”

- Creator

- Hollos, Clara

- Contributor

- Roth, Lászlo (illustrator)

- Date

- 1948

- Subject

- production story

- bread

- Rights

- Text copyright 1948 Clara Hollos. Illustrations copyright 1948 by Lászlo Roth. Text and images used under fair use.

- Source

- author's copy

- Bibliographic Citation

- Hollos, Clara and Roth, Lászlo. (1948). The Story of Your Bread. New York: Young World Books.