The Story of Your Coat

Item

- Title

- The Story of Your Coat

- Description

-

This first book by Clara Hollos follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Like the Petershams, Hollos offers a global perspective on textiles by following production from wool in Australia to a factory in New York City. The book was published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor and founder of Young World Books, International Publishers’ Children’s Series. Hollos and Kruckman humanize a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Each person involved in making the coat has a names, intelligence, skills, and aspirations. Small portraits of workers and capitalists suggest different races, ethnicities, and cultures for the characters.

Kruckman and Bacon both worked at New York City’s Jefferson School of Social Science, a Communist-affiliated institution, where Hollos wrote this story while taking Bacon’s class. Her picturebook pays tribute to the opening anecdote of Marx’s Capital, on how a coat produced by human hands becomes a commodity (Mickenberg and Nel, p. 67). Such a close relationship between production stories and the literature of political economy, trade, and manufacturing began in the early nineteenth-century, when authors of production stories sought to translate the principles of political economy for a mass audience, including children and self-educating adults. The classical political economist Adam Smith and the inventor and manufacturer Charles Babbage used anecdotes about common objects, such as pins or shirts, to illustrate their economic principles, and these same items, featured in children’s textbooks, made abstract concepts into concrete lessons. The codevelopment of children’s production stories with economic writings may explain why textiles such as wool and cotton are among the most common subjects used in both writings.

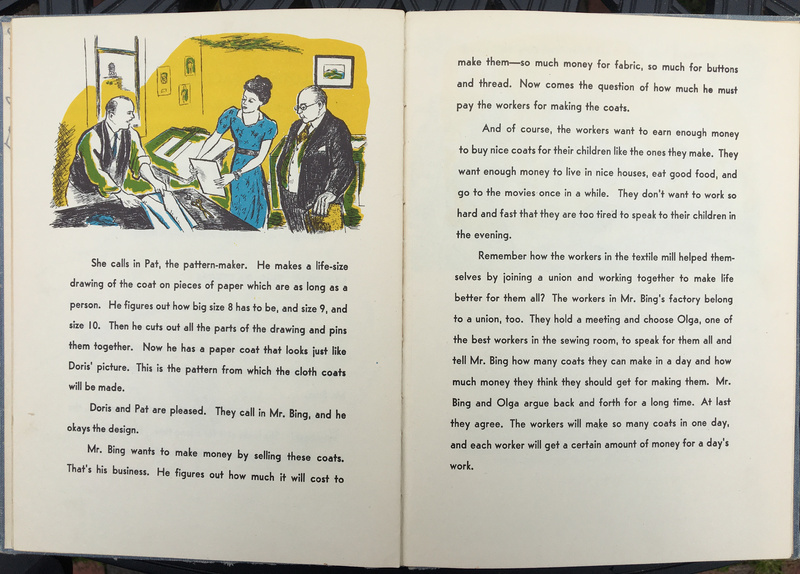

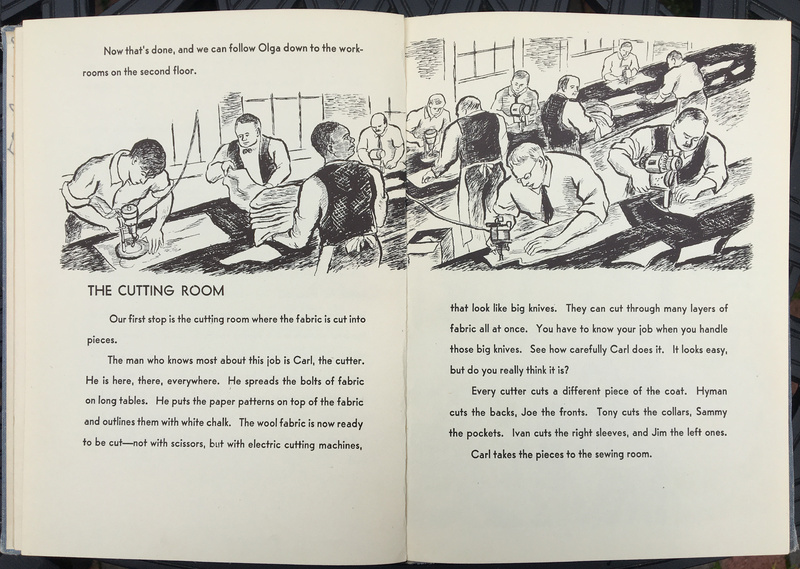

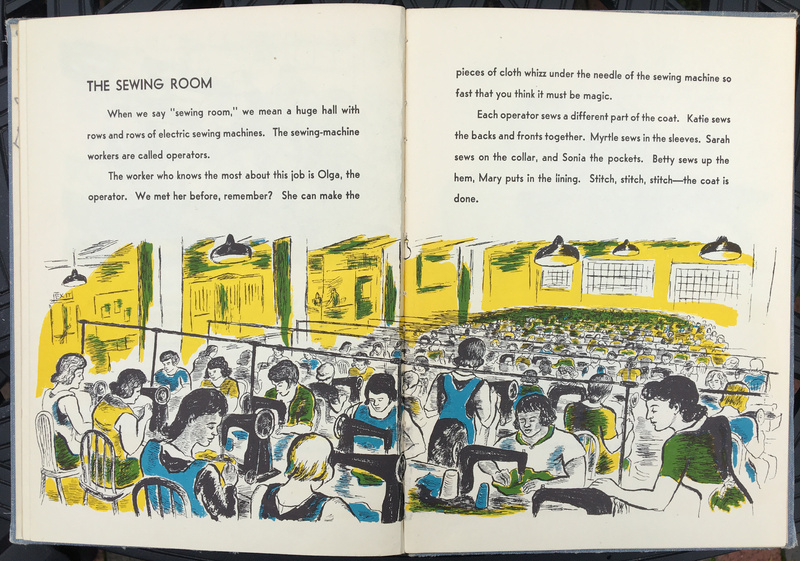

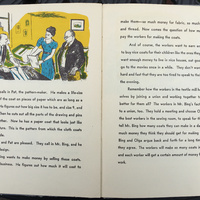

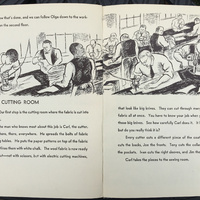

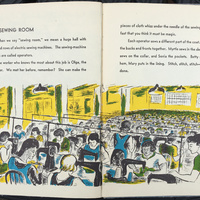

The personal attention given to the different workers appears on every spread, regardless of whether many or few people work together for a given task. The book’s early pages take place on farms and shipyards, where workers learn skills like sheep shearing and wool washing. Their narrative treatment is much the same as for the office and factory workers. Pat the pattern-maker collaboratively works to realize the fashion drawing made by Doris, the designer, before getting approval from Mr. Bing, the factory owner. Likewise, in the Cutting Room, dozens of male workers stand around long tables, drawn with strong diagonal lines that create a sense of energetic motion. The men have easily differentiated features. The text introduces readers to Carl the cutter, along with Hyman, Joe, Tony, Sammy, and Jim, among others, and explains the skill needed to cut wool cloth: “See how carefully Carl does it. It looks easy, but do you really think it is?” On the next spread, the treatment of women in “The Sewing Room” is similar. Dozens of women sew at tables that recede into the distance, filling a large factory floor, yet the first rows present lively faces in detail. The text introduces readers to “Olga, the operator,” mentioned earlier as the elected union representative, who “can make the pieces of cloth whizz under the needle of the sewing machine so fast that you think it must be magic.” Sewers Katie, Myrtle, Sarah, Sonia, Mary each handle a different part of the coat. Their cooperation even extends to Mr. Bing. In addition to paying for materials, Mr. Bing negotiates with the union to decide together how many coats the factory workers can make and how much they will get paid for them. Making coats creates mutual obligations between capitalists, workers, and consumers, with the terms of their social contract renegotiated through collective bargaining.

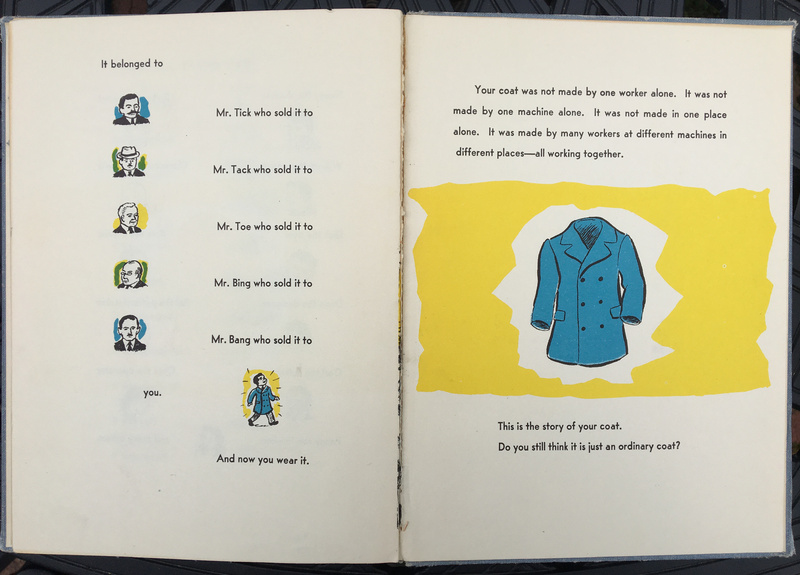

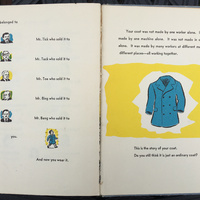

The book’s final pages summarize the coat’s journey from one worker to the next, while a separate page (shown here) summarizes the journey by purchase, from one capitalist to the next: from Mr. Tick, to Mr. Tack, to Mr. Tow, to Mr. Bing, to “Mr. Bang who sold it to you. And now you wear it.” Each person, worker, capitalist, and consumer, has a name and a small color portrait, including a young child at the end, wearing the coat. The right page shows a blue double-breasted wool coat, set off by a vibrant yellow background—an attractive coat that readers may want for themselves. The text on this final page reads: “Your coat was not made by one worker alone. It was not made by one machine alone. It was not made in one place alone. It was made by many workers at different machines in different places—all working together. This is the story of your coat. Do you still think it is just an ordinary coat?”

Celebrating global cooperation may seem in line with Hollos’s Marxist politics, but this message is a common one in production stories written by (or expressing) classical capitalist ideas over the last two centuries. Named characters, however, are highly unusual. Hollos rebels against the production story formula in the way she ties together coats with people. Production stories like to promise readers a surprise revelation. But in Hollos’s books, the surprise is how the ordinary becomes extraordinary. While that revelation applies first to the coat, the individualized attention given to the characters makes everyday people just as special.

- Creator

- Hollos, Clara (author)

- Contributor

- Kruckman, Herbert (illustrator)

- Date

- 1946

- Subject

- production story

- wool

- textiles

- Rights

- Text copyright 1946 Clara Hollos. Illustrations copyright 1946 by Herbert Kruckman. Text and images used under fair use.

- Source

- author's copy

- Bibliographic Citation

- Hollos, Clara and Roth, Lászlo. (1948). The Story of Your Bread. New York: Young World Books.