Items

In item set

Article images for "The Progress of Sugar"

-

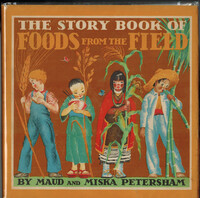

The Story Book of Foods from the Field: Wheat, Corn, Rice, Sugar During the interwar period, author-illustrator team Maud and Miska Petersham created some of the most memorable fiction stories and textbooks for children. With publishers’ renewed interest in children’s books about everyday life, the production story genre was revived in the United States with a series by Janet Smalley, closely followed by the Petersham’s comprehensive series comprised of five schoolbooks: The Story Book of The Things We Use (1933), about houses, food, and transportation; The Story Book of Earth’s Treasures (1935), about gold, coal, oil, iron, and steel; The Story Book of Wheels, Ships, Trains, Aircraft (1935); The Story Book of Foods from the Field (1936), about wheat, corn, rice, sugar; and The Story Book of Things We Wear (1939), about wool, cotton, silk, and rayon. Each of these five covered several commodities that could be purchased as separate volumes (Bader, 93-97). For instance, Foods from the Field includes material on sugar that also appears, with expanded content, in The Storybook of Sugar (1936). The Petersham volume on food thematizes the universal enjoyment of the fruits of the field, captured by the four figures of different cultural and racial appearances on the cover. Production stories favor repetitive formulas, both in text and image, that allow young readers to make interesting comparisons across different time periods, global locations, and human cultures. This cover’s multicultural message helps readers to reflect on our shared humanity, as all people must nourish their bodies with basic food. However, the cane figure placed next to the others also creates equivalency between families whose food access and fair wages may greatly differ. In practice, not all families are allowed to enjoy the products they work to produce, or conversely, families may have limited diets as a result of growing cash crops. A similar tension between the insensitivity of such comparisons and a desire for diverse representation or multicultural perspectives occurs in other production stories. The dust jacket for The Story Book of Foods from the Field shows a child with brown skin chewing cane. The same figure of a cane harvester chewing the cane appears in sugar production stories over the past two hundred years, changing to represent the labor force primarily responsible for sugar production, from enslaved Africans to free workers of different races and ethnicities. One possible cultural function of this perennial figure is to offer a cheerful veneer over questionable labor practices. Such an image reassures privileged consumers who purchase and eat sugar far away from where cane is grown that children involved in the sugar labor force have plenty of food—indeed, they enjoy treats, just like children everywhere. For more information on this figure, see The Story Book of Sugar.

The Story Book of Foods from the Field: Wheat, Corn, Rice, Sugar During the interwar period, author-illustrator team Maud and Miska Petersham created some of the most memorable fiction stories and textbooks for children. With publishers’ renewed interest in children’s books about everyday life, the production story genre was revived in the United States with a series by Janet Smalley, closely followed by the Petersham’s comprehensive series comprised of five schoolbooks: The Story Book of The Things We Use (1933), about houses, food, and transportation; The Story Book of Earth’s Treasures (1935), about gold, coal, oil, iron, and steel; The Story Book of Wheels, Ships, Trains, Aircraft (1935); The Story Book of Foods from the Field (1936), about wheat, corn, rice, sugar; and The Story Book of Things We Wear (1939), about wool, cotton, silk, and rayon. Each of these five covered several commodities that could be purchased as separate volumes (Bader, 93-97). For instance, Foods from the Field includes material on sugar that also appears, with expanded content, in The Storybook of Sugar (1936). The Petersham volume on food thematizes the universal enjoyment of the fruits of the field, captured by the four figures of different cultural and racial appearances on the cover. Production stories favor repetitive formulas, both in text and image, that allow young readers to make interesting comparisons across different time periods, global locations, and human cultures. This cover’s multicultural message helps readers to reflect on our shared humanity, as all people must nourish their bodies with basic food. However, the cane figure placed next to the others also creates equivalency between families whose food access and fair wages may greatly differ. In practice, not all families are allowed to enjoy the products they work to produce, or conversely, families may have limited diets as a result of growing cash crops. A similar tension between the insensitivity of such comparisons and a desire for diverse representation or multicultural perspectives occurs in other production stories. The dust jacket for The Story Book of Foods from the Field shows a child with brown skin chewing cane. The same figure of a cane harvester chewing the cane appears in sugar production stories over the past two hundred years, changing to represent the labor force primarily responsible for sugar production, from enslaved Africans to free workers of different races and ethnicities. One possible cultural function of this perennial figure is to offer a cheerful veneer over questionable labor practices. Such an image reassures privileged consumers who purchase and eat sugar far away from where cane is grown that children involved in the sugar labor force have plenty of food—indeed, they enjoy treats, just like children everywhere. For more information on this figure, see The Story Book of Sugar. -

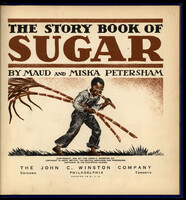

The Story Book of Sugar During the interwar period, author-illustrator team Maud and Miska Petersham created some of the most memorable fiction stories and textbooks for children. With publishers’ renewed interest in children’s books about everyday life, the production story genre was revived in the US with a series by Janet Smalley, closely followed by the Petersham’s comprehensive series comprised of five textbooks: The Story Book of The Things We Use (1933), about houses, food, and transportation; The Story Book of Earth’s Treasures (1935), about gold, coal, oil, iron, and steel; The Story Book of Wheels, Ships, Trains, Aircraft (1935); The Story Book of Foods from the Field (1936), about wheat, corn, rice, sugar; and The Story Book of Things We Wear (1939), about wool, cotton, silk, and rayon. Each of these five contain sections on different commodities that could be purchased as separate volumes. Most of the contents from The Storybook of Sugar (1936) also appear in the volume Foods from the Field (Bader, 93-97). This way of organizing a series by related commodities follows the same marketing strategy used by John Wallis, over a hundred years earlier. The title page for The Story Book of Sugar features a black child chewing cane. Another child chewing cane appears on the dust jacket for The Story Book of Foods from the Field. And a similar boy appears in the corner of an image depicting the cane harvest, titled “In the Sugar-Cane Field.” This cane harvester, chewing cut cane, has a long history. The figure appears in sugar production stories over the past two hundred years, changing to represent the labor force primarily responsible for sugar production, from enslaved Africans to free workers of different races and ethnicities. What is this figure’s perennial appeal? One possibility is that the harvester chewing cane encourages readers’ empathy without challenging their privilege: The image reassures privileged consumers who purchase and eat sugar far away from where cane is grown that children involved in the sugar labor force have plenty of food—indeed, they enjoy treats, just like children everywhere. While encouraging readers to sympathize with producers, such images also spread a cheerful veneer over questionable labor practices. In earlier production stories, the cane chewing figure originated with proslavery literature, which depicted slaves eating cane during harvest to contradict accounts of starvation in cane fields. However, the Petershams partially transform the image by making the cane chewer a child who meets the reader’s gaze. They also feature children eating grains in each segment of The Foods of the Field, where they eat bread, rice, and corn. This suggests that the Petershams are combining two visual tropes: the cane chewing harvester with the child consumer (who generally appears on the final spread of production stories, see for e.g. Hollos’s books). The Storybook of Sugar covers different sweeteners: honey, cane sugar, beet sugar, and maple syrup. Despite this global perspective on sweets, The Story Book of Sugar credits European ingenuity for sugar’s development by focalizing the story through white characters. For instance, the text acknowledges that mass cultivation of sugarcane began in India, yet readers learn about this fact from the perspective of Alexander’s soldier. The tall, armored man dominates the page, as a strong but relatively friendly figure, who “discovers” sugar during an invasion of regions that are now parts of Pakistan and India. Likewise, the section on Spanish sugar cane credits a “negro boy” sent to “the Brothers of the Jesuit Monastery in New Orleans” with figuring out how to cultivate cane, but the text glosses over the child’s enslavement by grouping him with the plants: “Again plants were sent to the Brothers in New Orleans. This time a Negro boy, who knew how to care for them, was sent with them.” The accompanying illustration positions the Spanish overseer in the foreground, his back to readers, which invites viewers to survey the sugar cane plantation from his perspective. The image includes enslaved persons, their bodies bent in labor, but signs of violence and coercion are downplayed. The modern refinery in the final spread captures another visual convention of production stories: the love of modern technology. Factory scenes usually make machinery the star, using repetition to create aesthetic appeal. Wondrous machines draw the viewer’s eye. We admire their size and strength, while human operators seem small and unimportant. In production stories, workers may appear as disembodied hands, or as nearly unrecognizable figures on a massive factory floor. (For a contrasting approach, see the recognizable faces in The Story of Your Coat.) In historical surveys of sugar production, machines capture the imagination after the abolition of slavery in the United States, and texts may even praise machines as “slaves,” as if modern factories ended slavery. However, technological progress does not necessarily coincide with social progress. Sugar production during the time of American slavery also relied on advanced manufacturing technologies and chemical processes. The enslaved persons who worked in mills, refineries, or other manufacturies had to learn specialized engineering knowledge, even though they were not paid or recognized for their skills. Additionally, modern workers may continue to face discrimination or poor working conditions, regardless of whether they use modern machinery.

The Story Book of Sugar During the interwar period, author-illustrator team Maud and Miska Petersham created some of the most memorable fiction stories and textbooks for children. With publishers’ renewed interest in children’s books about everyday life, the production story genre was revived in the US with a series by Janet Smalley, closely followed by the Petersham’s comprehensive series comprised of five textbooks: The Story Book of The Things We Use (1933), about houses, food, and transportation; The Story Book of Earth’s Treasures (1935), about gold, coal, oil, iron, and steel; The Story Book of Wheels, Ships, Trains, Aircraft (1935); The Story Book of Foods from the Field (1936), about wheat, corn, rice, sugar; and The Story Book of Things We Wear (1939), about wool, cotton, silk, and rayon. Each of these five contain sections on different commodities that could be purchased as separate volumes. Most of the contents from The Storybook of Sugar (1936) also appear in the volume Foods from the Field (Bader, 93-97). This way of organizing a series by related commodities follows the same marketing strategy used by John Wallis, over a hundred years earlier. The title page for The Story Book of Sugar features a black child chewing cane. Another child chewing cane appears on the dust jacket for The Story Book of Foods from the Field. And a similar boy appears in the corner of an image depicting the cane harvest, titled “In the Sugar-Cane Field.” This cane harvester, chewing cut cane, has a long history. The figure appears in sugar production stories over the past two hundred years, changing to represent the labor force primarily responsible for sugar production, from enslaved Africans to free workers of different races and ethnicities. What is this figure’s perennial appeal? One possibility is that the harvester chewing cane encourages readers’ empathy without challenging their privilege: The image reassures privileged consumers who purchase and eat sugar far away from where cane is grown that children involved in the sugar labor force have plenty of food—indeed, they enjoy treats, just like children everywhere. While encouraging readers to sympathize with producers, such images also spread a cheerful veneer over questionable labor practices. In earlier production stories, the cane chewing figure originated with proslavery literature, which depicted slaves eating cane during harvest to contradict accounts of starvation in cane fields. However, the Petershams partially transform the image by making the cane chewer a child who meets the reader’s gaze. They also feature children eating grains in each segment of The Foods of the Field, where they eat bread, rice, and corn. This suggests that the Petershams are combining two visual tropes: the cane chewing harvester with the child consumer (who generally appears on the final spread of production stories, see for e.g. Hollos’s books). The Storybook of Sugar covers different sweeteners: honey, cane sugar, beet sugar, and maple syrup. Despite this global perspective on sweets, The Story Book of Sugar credits European ingenuity for sugar’s development by focalizing the story through white characters. For instance, the text acknowledges that mass cultivation of sugarcane began in India, yet readers learn about this fact from the perspective of Alexander’s soldier. The tall, armored man dominates the page, as a strong but relatively friendly figure, who “discovers” sugar during an invasion of regions that are now parts of Pakistan and India. Likewise, the section on Spanish sugar cane credits a “negro boy” sent to “the Brothers of the Jesuit Monastery in New Orleans” with figuring out how to cultivate cane, but the text glosses over the child’s enslavement by grouping him with the plants: “Again plants were sent to the Brothers in New Orleans. This time a Negro boy, who knew how to care for them, was sent with them.” The accompanying illustration positions the Spanish overseer in the foreground, his back to readers, which invites viewers to survey the sugar cane plantation from his perspective. The image includes enslaved persons, their bodies bent in labor, but signs of violence and coercion are downplayed. The modern refinery in the final spread captures another visual convention of production stories: the love of modern technology. Factory scenes usually make machinery the star, using repetition to create aesthetic appeal. Wondrous machines draw the viewer’s eye. We admire their size and strength, while human operators seem small and unimportant. In production stories, workers may appear as disembodied hands, or as nearly unrecognizable figures on a massive factory floor. (For a contrasting approach, see the recognizable faces in The Story of Your Coat.) In historical surveys of sugar production, machines capture the imagination after the abolition of slavery in the United States, and texts may even praise machines as “slaves,” as if modern factories ended slavery. However, technological progress does not necessarily coincide with social progress. Sugar production during the time of American slavery also relied on advanced manufacturing technologies and chemical processes. The enslaved persons who worked in mills, refineries, or other manufacturies had to learn specialized engineering knowledge, even though they were not paid or recognized for their skills. Additionally, modern workers may continue to face discrimination or poor working conditions, regardless of whether they use modern machinery. -

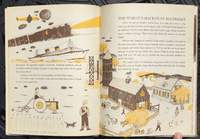

The Story of Your Bread Since the nineteenth-century, many production story series have included a volume on bread, a food that holds symbolic significance in Christian cultures that associate “daily bread” with both holy communion and basic sustenance. This second book on bread by Clara Hollos, published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor at Young world Books, follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Hollos humanizes a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Alongside technological inventions, Hollos describes the social context of production, including slavery, serfdom, and hunger. Illustrations by Lászlo Roth change style to reflect that “people all through the centuries had their own ways of drawing and painting,” as well as their own ways of making bread, the “king of foods.” Unlike her first book on wool coats, The Story of Your Bread offers a global historical survey of bread making, from “the Stone Age to our times,” in which farming and baking are indexes of civilization. This pan-historical approach to production stories takes after some of the earliest production stories. The Arts of Life by John Aiken (1803), for example, argues that technology, cooperation, and government initially arose from the desire to provide for three basic human needs: food, clothing, and shelter. Such production stories recapitulate the story of mankind organized around single commodities (sometimes groups of commodities), creating a progressive history that culminates in the modern, technologically enhanced production of the goods enjoyed by the reader. In production stories, this panhistorical approach often naturalizes the economic dominance of Europeans and European Americans. Nowhere is this more clear than in the final spread of The Story of Your Bread. Four human figures represent different phases in history: “Stone age child,” Egyptian child,” “Roman child,” and “Greek child.” Underneath these, the text states, “And now it give strength to the modern child, who is—YOU,” with a picture of a boy flexing his muscles. Although different races and ethnicities appear in Lászlo’s illustrations, history culminates in the strength of this white male child, who represents the book’s reader and bread eater. Books for younger readers balance a celebration of modern technology with assurances that things will stay the same. In “The Wheat Farm Run by Machinery,” a family farm relies on tractors and modern chemistry, and the farm is flanked by the transportation network that connects agriculture to the city: planes, trains, steamships, and suspension bridges. The farmer’s sons, Butch and Ned, study chemistry at the university, expertise they apply to test the soil and understand what plants will grow. Yet the emphasis on a generational family unit promises readers that farm life will continue from one generation to the next. New modes of communication and transportation will, the image suggests, actually support cultural continuity for families like this one. Similarly, another image of farming families during the harvest features a nostalgic scene of dancing and feasting, juxtaposed with a roadroad map of the US. Again, the modern family of farmers is predominantly European American, suggesting a racially narrow vision of who uses and prospers from new technologies. The book is more inclusive where class is concerned. The image of the large factory where people bake bread, for instance, shows workers with distinct faces and appearances, which gives a sense of individuality. The accompanying text describes the many different kinds of bread that bakeries produce for sale at the store and gives words for bread in different languages. Bread is the “king of foods,” not because only kings eat bread, but because everyone eats bread. Bread can feed large populations and keep them strong: “Most of the world’s work gets done by people who eat bread. They eat a great deal of bread because it is the cheapest of foods and they cannot afford to buy lots of meat and eggs and cheese. The healthiest workers are the ones who eat bread made of whole grains along with other good foods. By eating bread people get the strength they need to do the world’s work.” The page concludes by celebrating farmers for their important work, because they grow “the wheat from which our bread is made.”

The Story of Your Bread Since the nineteenth-century, many production story series have included a volume on bread, a food that holds symbolic significance in Christian cultures that associate “daily bread” with both holy communion and basic sustenance. This second book on bread by Clara Hollos, published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor at Young world Books, follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Hollos humanizes a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Alongside technological inventions, Hollos describes the social context of production, including slavery, serfdom, and hunger. Illustrations by Lászlo Roth change style to reflect that “people all through the centuries had their own ways of drawing and painting,” as well as their own ways of making bread, the “king of foods.” Unlike her first book on wool coats, The Story of Your Bread offers a global historical survey of bread making, from “the Stone Age to our times,” in which farming and baking are indexes of civilization. This pan-historical approach to production stories takes after some of the earliest production stories. The Arts of Life by John Aiken (1803), for example, argues that technology, cooperation, and government initially arose from the desire to provide for three basic human needs: food, clothing, and shelter. Such production stories recapitulate the story of mankind organized around single commodities (sometimes groups of commodities), creating a progressive history that culminates in the modern, technologically enhanced production of the goods enjoyed by the reader. In production stories, this panhistorical approach often naturalizes the economic dominance of Europeans and European Americans. Nowhere is this more clear than in the final spread of The Story of Your Bread. Four human figures represent different phases in history: “Stone age child,” Egyptian child,” “Roman child,” and “Greek child.” Underneath these, the text states, “And now it give strength to the modern child, who is—YOU,” with a picture of a boy flexing his muscles. Although different races and ethnicities appear in Lászlo’s illustrations, history culminates in the strength of this white male child, who represents the book’s reader and bread eater. Books for younger readers balance a celebration of modern technology with assurances that things will stay the same. In “The Wheat Farm Run by Machinery,” a family farm relies on tractors and modern chemistry, and the farm is flanked by the transportation network that connects agriculture to the city: planes, trains, steamships, and suspension bridges. The farmer’s sons, Butch and Ned, study chemistry at the university, expertise they apply to test the soil and understand what plants will grow. Yet the emphasis on a generational family unit promises readers that farm life will continue from one generation to the next. New modes of communication and transportation will, the image suggests, actually support cultural continuity for families like this one. Similarly, another image of farming families during the harvest features a nostalgic scene of dancing and feasting, juxtaposed with a roadroad map of the US. Again, the modern family of farmers is predominantly European American, suggesting a racially narrow vision of who uses and prospers from new technologies. The book is more inclusive where class is concerned. The image of the large factory where people bake bread, for instance, shows workers with distinct faces and appearances, which gives a sense of individuality. The accompanying text describes the many different kinds of bread that bakeries produce for sale at the store and gives words for bread in different languages. Bread is the “king of foods,” not because only kings eat bread, but because everyone eats bread. Bread can feed large populations and keep them strong: “Most of the world’s work gets done by people who eat bread. They eat a great deal of bread because it is the cheapest of foods and they cannot afford to buy lots of meat and eggs and cheese. The healthiest workers are the ones who eat bread made of whole grains along with other good foods. By eating bread people get the strength they need to do the world’s work.” The page concludes by celebrating farmers for their important work, because they grow “the wheat from which our bread is made.” -

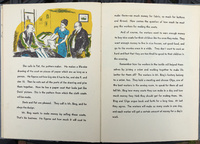

The Story of Your Coat This first book by Clara Hollos follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Like the Petershams, Hollos offers a global perspective on textiles by following production from wool in Australia to a factory in New York City. The book was published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor and founder of Young World Books, International Publishers’ Children’s Series. Hollos and Kruckman humanize a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Each person involved in making the coat has a names, intelligence, skills, and aspirations. Small portraits of workers and capitalists suggest different races, ethnicities, and cultures for the characters. Kruckman and Bacon both worked at New York City’s Jefferson School of Social Science, a Communist-affiliated institution, where Hollos wrote this story while taking Bacon’s class. Her picturebook pays tribute to the opening anecdote of Marx’s Capital, on how a coat produced by human hands becomes a commodity (Mickenberg and Nel, p. 67). Such a close relationship between production stories and the literature of political economy, trade, and manufacturing began in the early nineteenth-century, when authors of production stories sought to translate the principles of political economy for a mass audience, including children and self-educating adults. The classical political economist Adam Smith and the inventor and manufacturer Charles Babbage used anecdotes about common objects, such as pins or shirts, to illustrate their economic principles, and these same items, featured in children’s textbooks, made abstract concepts into concrete lessons. The codevelopment of children’s production stories with economic writings may explain why textiles such as wool and cotton are among the most common subjects used in both writings. The personal attention given to the different workers appears on every spread, regardless of whether many or few people work together for a given task. The book’s early pages take place on farms and shipyards, where workers learn skills like sheep shearing and wool washing. Their narrative treatment is much the same as for the office and factory workers. Pat the pattern-maker collaboratively works to realize the fashion drawing made by Doris, the designer, before getting approval from Mr. Bing, the factory owner. Likewise, in the Cutting Room, dozens of male workers stand around long tables, drawn with strong diagonal lines that create a sense of energetic motion. The men have easily differentiated features. The text introduces readers to Carl the cutter, along with Hyman, Joe, Tony, Sammy, and Jim, among others, and explains the skill needed to cut wool cloth: “See how carefully Carl does it. It looks easy, but do you really think it is?” On the next spread, the treatment of women in “The Sewing Room” is similar. Dozens of women sew at tables that recede into the distance, filling a large factory floor, yet the first rows present lively faces in detail. The text introduces readers to “Olga, the operator,” mentioned earlier as the elected union representative, who “can make the pieces of cloth whizz under the needle of the sewing machine so fast that you think it must be magic.” Sewers Katie, Myrtle, Sarah, Sonia, Mary each handle a different part of the coat. Their cooperation even extends to Mr. Bing. In addition to paying for materials, Mr. Bing negotiates with the union to decide together how many coats the factory workers can make and how much they will get paid for them. Making coats creates mutual obligations between capitalists, workers, and consumers, with the terms of their social contract renegotiated through collective bargaining. The book’s final pages summarize the coat’s journey from one worker to the next, while a separate page (shown here) summarizes the journey by purchase, from one capitalist to the next: from Mr. Tick, to Mr. Tack, to Mr. Tow, to Mr. Bing, to “Mr. Bang who sold it to you. And now you wear it.” Each person, worker, capitalist, and consumer, has a name and a small color portrait, including a young child at the end, wearing the coat. The right page shows a blue double-breasted wool coat, set off by a vibrant yellow background—an attractive coat that readers may want for themselves. The text on this final page reads: “Your coat was not made by one worker alone. It was not made by one machine alone. It was not made in one place alone. It was made by many workers at different machines in different places—all working together. This is the story of your coat. Do you still think it is just an ordinary coat?” Celebrating global cooperation may seem in line with Hollos’s Marxist politics, but this message is a common one in production stories written by (or expressing) classical capitalist ideas over the last two centuries. Named characters, however, are highly unusual. Hollos rebels against the production story formula in the way she ties together coats with people. Production stories like to promise readers a surprise revelation. But in Hollos’s books, the surprise is how the ordinary becomes extraordinary. While that revelation applies first to the coat, the individualized attention given to the characters makes everyday people just as special.

The Story of Your Coat This first book by Clara Hollos follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Like the Petershams, Hollos offers a global perspective on textiles by following production from wool in Australia to a factory in New York City. The book was published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor and founder of Young World Books, International Publishers’ Children’s Series. Hollos and Kruckman humanize a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Each person involved in making the coat has a names, intelligence, skills, and aspirations. Small portraits of workers and capitalists suggest different races, ethnicities, and cultures for the characters. Kruckman and Bacon both worked at New York City’s Jefferson School of Social Science, a Communist-affiliated institution, where Hollos wrote this story while taking Bacon’s class. Her picturebook pays tribute to the opening anecdote of Marx’s Capital, on how a coat produced by human hands becomes a commodity (Mickenberg and Nel, p. 67). Such a close relationship between production stories and the literature of political economy, trade, and manufacturing began in the early nineteenth-century, when authors of production stories sought to translate the principles of political economy for a mass audience, including children and self-educating adults. The classical political economist Adam Smith and the inventor and manufacturer Charles Babbage used anecdotes about common objects, such as pins or shirts, to illustrate their economic principles, and these same items, featured in children’s textbooks, made abstract concepts into concrete lessons. The codevelopment of children’s production stories with economic writings may explain why textiles such as wool and cotton are among the most common subjects used in both writings. The personal attention given to the different workers appears on every spread, regardless of whether many or few people work together for a given task. The book’s early pages take place on farms and shipyards, where workers learn skills like sheep shearing and wool washing. Their narrative treatment is much the same as for the office and factory workers. Pat the pattern-maker collaboratively works to realize the fashion drawing made by Doris, the designer, before getting approval from Mr. Bing, the factory owner. Likewise, in the Cutting Room, dozens of male workers stand around long tables, drawn with strong diagonal lines that create a sense of energetic motion. The men have easily differentiated features. The text introduces readers to Carl the cutter, along with Hyman, Joe, Tony, Sammy, and Jim, among others, and explains the skill needed to cut wool cloth: “See how carefully Carl does it. It looks easy, but do you really think it is?” On the next spread, the treatment of women in “The Sewing Room” is similar. Dozens of women sew at tables that recede into the distance, filling a large factory floor, yet the first rows present lively faces in detail. The text introduces readers to “Olga, the operator,” mentioned earlier as the elected union representative, who “can make the pieces of cloth whizz under the needle of the sewing machine so fast that you think it must be magic.” Sewers Katie, Myrtle, Sarah, Sonia, Mary each handle a different part of the coat. Their cooperation even extends to Mr. Bing. In addition to paying for materials, Mr. Bing negotiates with the union to decide together how many coats the factory workers can make and how much they will get paid for them. Making coats creates mutual obligations between capitalists, workers, and consumers, with the terms of their social contract renegotiated through collective bargaining. The book’s final pages summarize the coat’s journey from one worker to the next, while a separate page (shown here) summarizes the journey by purchase, from one capitalist to the next: from Mr. Tick, to Mr. Tack, to Mr. Tow, to Mr. Bing, to “Mr. Bang who sold it to you. And now you wear it.” Each person, worker, capitalist, and consumer, has a name and a small color portrait, including a young child at the end, wearing the coat. The right page shows a blue double-breasted wool coat, set off by a vibrant yellow background—an attractive coat that readers may want for themselves. The text on this final page reads: “Your coat was not made by one worker alone. It was not made by one machine alone. It was not made in one place alone. It was made by many workers at different machines in different places—all working together. This is the story of your coat. Do you still think it is just an ordinary coat?” Celebrating global cooperation may seem in line with Hollos’s Marxist politics, but this message is a common one in production stories written by (or expressing) classical capitalist ideas over the last two centuries. Named characters, however, are highly unusual. Hollos rebels against the production story formula in the way she ties together coats with people. Production stories like to promise readers a surprise revelation. But in Hollos’s books, the surprise is how the ordinary becomes extraordinary. While that revelation applies first to the coat, the individualized attention given to the characters makes everyday people just as special. -

Tobe This item description is currently under development.

Tobe This item description is currently under development.