-

The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar

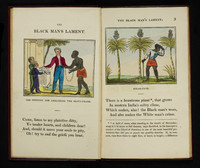

The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar One of the earliest abolitionist books for children, this production story by the Quaker abolitionist novelist and poet, Amelia Alderson Opie is a call to political action that eschews the pleasures of consumption. The copperplate engravings are by an unknown artist, but the style indicates that children’s publishers Harvey and Darton, a prominent abolitionist and Quaker firm, used the same artist for their reprint of William Cowper’s “The Negro’s Complaint” (Cutter, p. 71). According to historian Martha Cutter, the illustrator takes care to represent “distinctive (rather than stereotypical) persons,” who allow for intersubjectivity by meeting the viewer’s gaze (p. 82).

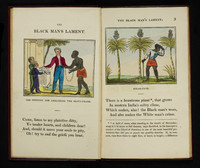

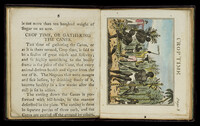

Opie adapts the production story formula to foreground her abolitionist message, by opening her story with a plea to readers “to end the griefs you hear (p.2). The opening illustration shows two children signing a petition in support of abolition of the slave trade. A man in chains on the right resembles Wedgewood’s often circulated abolitionist image of a supplicant slave, but rather than kneeling, he stands and reaches out to the children. The right-hand page introduces sugar cane as a “beauteous plant” that “makes, alas! The Blank man’s woes, / And also makes the White man’s crimes,” with a lengthy small print footnote on sugar cane’s appearance and cultivation (p. 3). Readers accustomed to the scientific language of production stories would be surprised to find the actual process of sugar making relegated to the footnotes. Again, on the next spread, technical detail that would usually occupy a prominent place remains peripheral, while the emotional appeal of a human story dominates (p. 4). At this moment in the story, the enslaved man takes over narration until its conclusion. The accompanying illustration shows him “torn” from his wife and infant by men wielding swords and cudgels (p. 5).

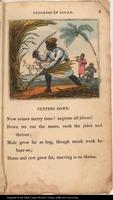

Some of the images, such as “Cutting Down the Sugar-Cane” and “The Bruising-Mill” (pp. 16-17) closely resemble those provided in other sugar production narratives, such as Negro Labour (1809) or William Newman’s A History of a Pound of Sugar (1861). This conformity to generic expectations makes the unique text below the images all the more striking. Harvest time is usually portrayed in sugar production narratives as a joyous, healthful time when harvesters gain weight by chewing the ends of cut cane. But in a departure from this formula, Opie’s speaker describes harvest as the beginning of “our saddest pains; / For then we toil both day and night.” Instead of feeding themselves, they feed an ever-hungry grinding mill.

-

The History of a Pound of Sugar

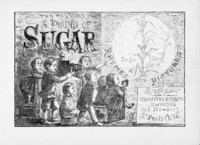

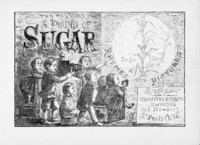

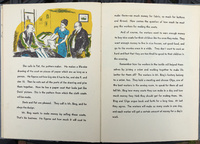

The History of a Pound of Sugar William Newman wrote a production story series on bread, tea, sugar, coals, and cotton, each printed separately or available together in a single volume. At the date of publication, slavery had ended in the British West Indies but not in the US, where the Civil War had just begun. This volume on sugar begins, on the title page, with white English children eagerly consuming information about sugar cane, delivered in the medium of a magic lantern show, and it ends with white English children eating sugar from a barrel outside of a general store. Creating parallels between these two acts of consumption equates reading with eating and asks readers to identify with the privileged position of white English child consumers. The children operate the magic lantern show themselves. Such visual control over the entire sugar-making process appears throughout the book. The spread showing “Planting,” for instance, is focalized through the perspective of the “Planter,” who “walks around / With eagle glance, and all controls” (p.3). Production stories like this one give children a visual “survey” of the process, using visual strategies such as the elevated view, that give a sense of ownership and control. As a result, child readers are asked to identify with positions of power, such as managers and overseers, rather than with characters performing physical labor or working with machines.

The book is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. But the process of refining sugar from brown sugar to white gives the text an opportunity to drive home racial hierarchies to readers. At this time, black workers, often slaves, created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. The description of this process passes judgment on the people who work the sugar at various stages: ‘Safe on our shores; the Sugar still / Is only “Raw,” or unrefined: / This is called “Moist.” The Baker’s skill, / With fire and various aids combined, / Makes of it “Lump”—crisp, crystal white, / Sweet to the taste, and fair to sight’ (p. 10). Such racist comments on the superiority of whiteness are commonplace in nineteenth-century sugar production stories.

The cover’s portrayal of other mediated versions of this story suggests that publishers Griffith & Farran may have produced additional learning aids to accompany Newman’s books, such as magic lantern slides, games, or prints to hand on walls. Selling different mediums to teach this material was a strategy used by early-nineteenth-century publisher John Wallis.

-

Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar

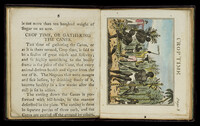

Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar is one of the earliest sugar production stories created for children. Published two years after the abolition of the slave trade in Britain, the book begins by criticizing slavery but ultimately supports its continuation, “for it is now become the interest of the Planter to take more care of his Slaves, to feed them better, and to work them more moderately than he used to do, since he cannot now supply the places of those who die among them, as he could do before the abolition of that wicked Traffic, by the purchase of a fresh parcel, whenever a Slave-ship brought in a Cargo from Africa” (p. 4). Negro Labour shows how the abolition of the slave trade could be used to justify slavery itself. Contrary to the author’s predictions, ending the slave trade did not end overwork, starvation, and torture on plantations. Instead, selling enslaved children became a larger part of the slave plantation economy.

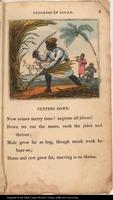

The majority of the text focuses on technical details of sugar production, while avoiding overt acknowledgement of slavery or suggesting any political action on the part of readers. Accompanying illustrations, likely crafted without seeing the text, are often at odds with the apologist tone of the text. The section titled “Crop time, or Gathering the Canes,” for instance, describes the cane harvest as “a season of great mirth and festivity; and so highly nourishing to the bodily frame is the juice of the Cane that every animal derives health and vigour from the use of it. The Negroes that were meagre and sick before, by drinking freely of it, become healthy in a few weeks after the mill is set in action.” The lie that enslaved persons share in the harvest benefits attempts to counter abolitionist accounts of starvation and ignores that enslaved persons worked long hours during harvest and faced dangerous conditions in sugar mills. (A similar depiction of harvest time appears in Cuffy the Negro’s Doggrel Description of the Progress of Sugar.) An accompanying illustration, however, frankly depicts violence. Six black men cut and gather the cane, while two of them look over their shoulder in fear at a black overseer with a whip.

-

The Story of Your Coat

The Story of Your Coat This first book by Clara Hollos follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Like the Petershams, Hollos offers a global perspective on textiles by following production from wool in Australia to a factory in New York City. The book was published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor and founder of Young World Books, International Publishers’ Children’s Series. Hollos and Kruckman humanize a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Each person involved in making the coat has a names, intelligence, skills, and aspirations. Small portraits of workers and capitalists suggest different races, ethnicities, and cultures for the characters.

Kruckman and Bacon both worked at New York City’s Jefferson School of Social Science, a Communist-affiliated institution, where Hollos wrote this story while taking Bacon’s class. Her picturebook pays tribute to the opening anecdote of Marx’s Capital, on how a coat produced by human hands becomes a commodity (Mickenberg and Nel, p. 67). Such a close relationship between production stories and the literature of political economy, trade, and manufacturing began in the early nineteenth-century, when authors of production stories sought to translate the principles of political economy for a mass audience, including children and self-educating adults. The classical political economist Adam Smith and the inventor and manufacturer Charles Babbage used anecdotes about common objects, such as pins or shirts, to illustrate their economic principles, and these same items, featured in children’s textbooks, made abstract concepts into concrete lessons. The codevelopment of children’s production stories with economic writings may explain why textiles such as wool and cotton are among the most common subjects used in both writings.

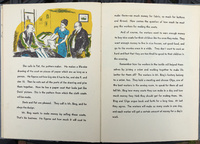

The personal attention given to the different workers appears on every spread, regardless of whether many or few people work together for a given task. The book’s early pages take place on farms and shipyards, where workers learn skills like sheep shearing and wool washing. Their narrative treatment is much the same as for the office and factory workers. Pat the pattern-maker collaboratively works to realize the fashion drawing made by Doris, the designer, before getting approval from Mr. Bing, the factory owner. Likewise, in the Cutting Room, dozens of male workers stand around long tables, drawn with strong diagonal lines that create a sense of energetic motion. The men have easily differentiated features. The text introduces readers to Carl the cutter, along with Hyman, Joe, Tony, Sammy, and Jim, among others, and explains the skill needed to cut wool cloth: “See how carefully Carl does it. It looks easy, but do you really think it is?” On the next spread, the treatment of women in “The Sewing Room” is similar. Dozens of women sew at tables that recede into the distance, filling a large factory floor, yet the first rows present lively faces in detail. The text introduces readers to “Olga, the operator,” mentioned earlier as the elected union representative, who “can make the pieces of cloth whizz under the needle of the sewing machine so fast that you think it must be magic.” Sewers Katie, Myrtle, Sarah, Sonia, Mary each handle a different part of the coat. Their cooperation even extends to Mr. Bing. In addition to paying for materials, Mr. Bing negotiates with the union to decide together how many coats the factory workers can make and how much they will get paid for them. Making coats creates mutual obligations between capitalists, workers, and consumers, with the terms of their social contract renegotiated through collective bargaining.

The book’s final pages summarize the coat’s journey from one worker to the next, while a separate page (shown here) summarizes the journey by purchase, from one capitalist to the next: from Mr. Tick, to Mr. Tack, to Mr. Tow, to Mr. Bing, to “Mr. Bang who sold it to you. And now you wear it.” Each person, worker, capitalist, and consumer, has a name and a small color portrait, including a young child at the end, wearing the coat. The right page shows a blue double-breasted wool coat, set off by a vibrant yellow background—an attractive coat that readers may want for themselves. The text on this final page reads: “Your coat was not made by one worker alone. It was not made by one machine alone. It was not made in one place alone. It was made by many workers at different machines in different places—all working together. This is the story of your coat. Do you still think it is just an ordinary coat?”

Celebrating global cooperation may seem in line with Hollos’s Marxist politics, but this message is a common one in production stories written by (or expressing) classical capitalist ideas over the last two centuries. Named characters, however, are highly unusual. Hollos rebels against the production story formula in the way she ties together coats with people. Production stories like to promise readers a surprise revelation. But in Hollos’s books, the surprise is how the ordinary becomes extraordinary. While that revelation applies first to the coat, the individualized attention given to the characters makes everyday people just as special.

-

The Story of Your Bread

The Story of Your Bread Since the nineteenth-century, many production story series have included a volume on bread, a food that holds symbolic significance in Christian cultures that associate “daily bread” with both holy communion and basic sustenance. This second book on bread by Clara Hollos, published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor at Young world Books, follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Hollos humanizes a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Alongside technological inventions, Hollos describes the social context of production, including slavery, serfdom, and hunger. Illustrations by Lászlo Roth change style to reflect that “people all through the centuries had their own ways of drawing and painting,” as well as their own ways of making bread, the “king of foods.”

Unlike her first book on wool coats, The Story of Your Bread offers a global historical survey of bread making, from “the Stone Age to our times,” in which farming and baking are indexes of civilization. This pan-historical approach to production stories takes after some of the earliest production stories. The Arts of Life by John Aiken (1803), for example, argues that technology, cooperation, and government initially arose from the desire to provide for three basic human needs: food, clothing, and shelter. Such production stories recapitulate the story of mankind organized around single commodities (sometimes groups of commodities), creating a progressive history that culminates in the modern, technologically enhanced production of the goods enjoyed by the reader.

In production stories, this panhistorical approach often naturalizes the economic dominance of Europeans and European Americans. Nowhere is this more clear than in the final spread of The Story of Your Bread. Four human figures represent different phases in history: “Stone age child,” Egyptian child,” “Roman child,” and “Greek child.” Underneath these, the text states, “And now it give strength to the modern child, who is—YOU,” with a picture of a boy flexing his muscles. Although different races and ethnicities appear in Lászlo’s illustrations, history culminates in the strength of this white male child, who represents the book’s reader and bread eater.

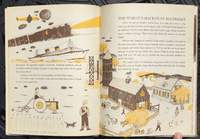

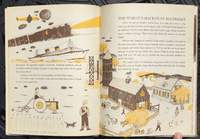

Books for younger readers balance a celebration of modern technology with assurances that things will stay the same. In “The Wheat Farm Run by Machinery,” a family farm relies on tractors and modern chemistry, and the farm is flanked by the transportation network that connects agriculture to the city: planes, trains, steamships, and suspension bridges. The farmer’s sons, Butch and Ned, study chemistry at the university, expertise they apply to test the soil and understand what plants will grow. Yet the emphasis on a generational family unit promises readers that farm life will continue from one generation to the next. New modes of communication and transportation will, the image suggests, actually support cultural continuity for families like this one. Similarly, another image of farming families during the harvest features a nostalgic scene of dancing and feasting, juxtaposed with a roadroad map of the US. Again, the modern family of farmers is predominantly European American, suggesting a racially narrow vision of who uses and prospers from new technologies.

The book is more inclusive where class is concerned. The image of the large factory where people bake bread, for instance, shows workers with distinct faces and appearances, which gives a sense of individuality. The accompanying text describes the many different kinds of bread that bakeries produce for sale at the store and gives words for bread in different languages. Bread is the “king of foods,” not because only kings eat bread, but because everyone eats bread. Bread can feed large populations and keep them strong: “Most of the world’s work gets done by people who eat bread. They eat a great deal of bread because it is the cheapest of foods and they cannot afford to buy lots of meat and eggs and cheese. The healthiest workers are the ones who eat bread made of whole grains along with other good foods. By eating bread people get the strength they need to do the world’s work.” The page concludes by celebrating farmers for their important work, because they grow “the wheat from which our bread is made.”

-

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Cotton

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Cotton John Wallis printed three production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in a contrived dialect by the fictional character named Cuffy. Recently arrived in London from the West Indies, Cuffy learned how these commodities are made while enslaved, and he promises to tell audiences what he knows. The frontispiece shows the pleasures of consuming these goods, as ladies select cotton cloth for purchase from a smiling salesperson. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons and encourages consumption of cotton products.

-

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar Each page of this chapbook features a single illustration depicting one part in the process of making sugar. Readers follow sugar production from slave labor in West Indies plantation cane fields to sugar refineries in British port cities, and finally, to confectioners shops where children purchase sugary treats. John Wallis printed a series of three such production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in contrived dialect and doggerel poetry by the fictional character called Cuffy. Formerly enslaved in the West Indies and recently arrived in London, Cuffy promises to tell audiences what he knows about making these commodities in exchange for coin. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons. Without explicitly supporting slavery, the book effectively defends slavery by depicting work on sugar plantations as so enjoyable that Cuffy regrets leaving. Cane harvesting is a “merry time!” when enslaved persons (denigrated here as livestock) “cut the canes, suck the juice and thrive; / Mule grow fat as hog, though much work he bear-ee; / Horse and cow grow far, starving is no there” (p9). In fact, many enslaved persons starved at harvest time because of the relentless pace of work. The later stages of sugar production in England are shown performed by free white persons. At the conclusion, Cuffy thanks the reader for “kind relief,” or money given to tell his story, directly involving readers in the slave-sugar economy as consumers.

The chapbook is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. Yet the racial context of sugar production makes this process take on metaphorical meanings at every turn. Enslaved Africans created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. Sugar production stories used this language of brown, white, and refined, to continually remind readers of constructed racial hierarchies. Moreover, the process of refining sugar required animal blood, or as Cuffy describes: “To make sugar white (sure he be a ninny!) / Blood, and nasty something, baker now put in-ee” (p.15). Beginning in the 1790s, many abolitionist politicians and poets alluded to this fact to make eating slave sugar disgusting. People should boycott sugar, they argued, because slavery is a cannibalistic institution. Since harvesting cane causes the death of overworked, starved enslaved persons, sugar is essentially refined in human blood (See also Sandiford, 2000, p. 124; Sheller, 2003, pp. 88-97).

This abolitionist interpretation of the material process—what Timothy Morton calls the “blood sugar topos” (1998, p. 88)—was disseminated so widely that Wallis’s readers may recall this message while reading Cuffy’s account. The image of the “Confectioner,” for instance, shows a plump white man boiling a purple-red liquid in a large pan, suspended over an open stove flame. Although the text describes the liquid as “sugar-plum or candy,” the purple-red coloring may remind readers of human blood. Production stories that condone slavery, such as this one, tend to double-down on the literal, material process of refining sugar, as a way to avoid alluding to the blood sugar topos. This strategy is another example of how production stories can use scientific language to try to avoid addressing social conflict.

The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar One of the earliest abolitionist books for children, this production story by the Quaker abolitionist novelist and poet, Amelia Alderson Opie is a call to political action that eschews the pleasures of consumption. The copperplate engravings are by an unknown artist, but the style indicates that children’s publishers Harvey and Darton, a prominent abolitionist and Quaker firm, used the same artist for their reprint of William Cowper’s “The Negro’s Complaint” (Cutter, p. 71). According to historian Martha Cutter, the illustrator takes care to represent “distinctive (rather than stereotypical) persons,” who allow for intersubjectivity by meeting the viewer’s gaze (p. 82). Opie adapts the production story formula to foreground her abolitionist message, by opening her story with a plea to readers “to end the griefs you hear (p.2). The opening illustration shows two children signing a petition in support of abolition of the slave trade. A man in chains on the right resembles Wedgewood’s often circulated abolitionist image of a supplicant slave, but rather than kneeling, he stands and reaches out to the children. The right-hand page introduces sugar cane as a “beauteous plant” that “makes, alas! The Blank man’s woes, / And also makes the White man’s crimes,” with a lengthy small print footnote on sugar cane’s appearance and cultivation (p. 3). Readers accustomed to the scientific language of production stories would be surprised to find the actual process of sugar making relegated to the footnotes. Again, on the next spread, technical detail that would usually occupy a prominent place remains peripheral, while the emotional appeal of a human story dominates (p. 4). At this moment in the story, the enslaved man takes over narration until its conclusion. The accompanying illustration shows him “torn” from his wife and infant by men wielding swords and cudgels (p. 5). Some of the images, such as “Cutting Down the Sugar-Cane” and “The Bruising-Mill” (pp. 16-17) closely resemble those provided in other sugar production narratives, such as Negro Labour (1809) or William Newman’s A History of a Pound of Sugar (1861). This conformity to generic expectations makes the unique text below the images all the more striking. Harvest time is usually portrayed in sugar production narratives as a joyous, healthful time when harvesters gain weight by chewing the ends of cut cane. But in a departure from this formula, Opie’s speaker describes harvest as the beginning of “our saddest pains; / For then we toil both day and night.” Instead of feeding themselves, they feed an ever-hungry grinding mill.

The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar One of the earliest abolitionist books for children, this production story by the Quaker abolitionist novelist and poet, Amelia Alderson Opie is a call to political action that eschews the pleasures of consumption. The copperplate engravings are by an unknown artist, but the style indicates that children’s publishers Harvey and Darton, a prominent abolitionist and Quaker firm, used the same artist for their reprint of William Cowper’s “The Negro’s Complaint” (Cutter, p. 71). According to historian Martha Cutter, the illustrator takes care to represent “distinctive (rather than stereotypical) persons,” who allow for intersubjectivity by meeting the viewer’s gaze (p. 82). Opie adapts the production story formula to foreground her abolitionist message, by opening her story with a plea to readers “to end the griefs you hear (p.2). The opening illustration shows two children signing a petition in support of abolition of the slave trade. A man in chains on the right resembles Wedgewood’s often circulated abolitionist image of a supplicant slave, but rather than kneeling, he stands and reaches out to the children. The right-hand page introduces sugar cane as a “beauteous plant” that “makes, alas! The Blank man’s woes, / And also makes the White man’s crimes,” with a lengthy small print footnote on sugar cane’s appearance and cultivation (p. 3). Readers accustomed to the scientific language of production stories would be surprised to find the actual process of sugar making relegated to the footnotes. Again, on the next spread, technical detail that would usually occupy a prominent place remains peripheral, while the emotional appeal of a human story dominates (p. 4). At this moment in the story, the enslaved man takes over narration until its conclusion. The accompanying illustration shows him “torn” from his wife and infant by men wielding swords and cudgels (p. 5). Some of the images, such as “Cutting Down the Sugar-Cane” and “The Bruising-Mill” (pp. 16-17) closely resemble those provided in other sugar production narratives, such as Negro Labour (1809) or William Newman’s A History of a Pound of Sugar (1861). This conformity to generic expectations makes the unique text below the images all the more striking. Harvest time is usually portrayed in sugar production narratives as a joyous, healthful time when harvesters gain weight by chewing the ends of cut cane. But in a departure from this formula, Opie’s speaker describes harvest as the beginning of “our saddest pains; / For then we toil both day and night.” Instead of feeding themselves, they feed an ever-hungry grinding mill. The History of a Pound of Sugar William Newman wrote a production story series on bread, tea, sugar, coals, and cotton, each printed separately or available together in a single volume. At the date of publication, slavery had ended in the British West Indies but not in the US, where the Civil War had just begun. This volume on sugar begins, on the title page, with white English children eagerly consuming information about sugar cane, delivered in the medium of a magic lantern show, and it ends with white English children eating sugar from a barrel outside of a general store. Creating parallels between these two acts of consumption equates reading with eating and asks readers to identify with the privileged position of white English child consumers. The children operate the magic lantern show themselves. Such visual control over the entire sugar-making process appears throughout the book. The spread showing “Planting,” for instance, is focalized through the perspective of the “Planter,” who “walks around / With eagle glance, and all controls” (p.3). Production stories like this one give children a visual “survey” of the process, using visual strategies such as the elevated view, that give a sense of ownership and control. As a result, child readers are asked to identify with positions of power, such as managers and overseers, rather than with characters performing physical labor or working with machines. The book is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. But the process of refining sugar from brown sugar to white gives the text an opportunity to drive home racial hierarchies to readers. At this time, black workers, often slaves, created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. The description of this process passes judgment on the people who work the sugar at various stages: ‘Safe on our shores; the Sugar still / Is only “Raw,” or unrefined: / This is called “Moist.” The Baker’s skill, / With fire and various aids combined, / Makes of it “Lump”—crisp, crystal white, / Sweet to the taste, and fair to sight’ (p. 10). Such racist comments on the superiority of whiteness are commonplace in nineteenth-century sugar production stories. The cover’s portrayal of other mediated versions of this story suggests that publishers Griffith & Farran may have produced additional learning aids to accompany Newman’s books, such as magic lantern slides, games, or prints to hand on walls. Selling different mediums to teach this material was a strategy used by early-nineteenth-century publisher John Wallis.

The History of a Pound of Sugar William Newman wrote a production story series on bread, tea, sugar, coals, and cotton, each printed separately or available together in a single volume. At the date of publication, slavery had ended in the British West Indies but not in the US, where the Civil War had just begun. This volume on sugar begins, on the title page, with white English children eagerly consuming information about sugar cane, delivered in the medium of a magic lantern show, and it ends with white English children eating sugar from a barrel outside of a general store. Creating parallels between these two acts of consumption equates reading with eating and asks readers to identify with the privileged position of white English child consumers. The children operate the magic lantern show themselves. Such visual control over the entire sugar-making process appears throughout the book. The spread showing “Planting,” for instance, is focalized through the perspective of the “Planter,” who “walks around / With eagle glance, and all controls” (p.3). Production stories like this one give children a visual “survey” of the process, using visual strategies such as the elevated view, that give a sense of ownership and control. As a result, child readers are asked to identify with positions of power, such as managers and overseers, rather than with characters performing physical labor or working with machines. The book is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. But the process of refining sugar from brown sugar to white gives the text an opportunity to drive home racial hierarchies to readers. At this time, black workers, often slaves, created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. The description of this process passes judgment on the people who work the sugar at various stages: ‘Safe on our shores; the Sugar still / Is only “Raw,” or unrefined: / This is called “Moist.” The Baker’s skill, / With fire and various aids combined, / Makes of it “Lump”—crisp, crystal white, / Sweet to the taste, and fair to sight’ (p. 10). Such racist comments on the superiority of whiteness are commonplace in nineteenth-century sugar production stories. The cover’s portrayal of other mediated versions of this story suggests that publishers Griffith & Farran may have produced additional learning aids to accompany Newman’s books, such as magic lantern slides, games, or prints to hand on walls. Selling different mediums to teach this material was a strategy used by early-nineteenth-century publisher John Wallis. Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar is one of the earliest sugar production stories created for children. Published two years after the abolition of the slave trade in Britain, the book begins by criticizing slavery but ultimately supports its continuation, “for it is now become the interest of the Planter to take more care of his Slaves, to feed them better, and to work them more moderately than he used to do, since he cannot now supply the places of those who die among them, as he could do before the abolition of that wicked Traffic, by the purchase of a fresh parcel, whenever a Slave-ship brought in a Cargo from Africa” (p. 4). Negro Labour shows how the abolition of the slave trade could be used to justify slavery itself. Contrary to the author’s predictions, ending the slave trade did not end overwork, starvation, and torture on plantations. Instead, selling enslaved children became a larger part of the slave plantation economy. The majority of the text focuses on technical details of sugar production, while avoiding overt acknowledgement of slavery or suggesting any political action on the part of readers. Accompanying illustrations, likely crafted without seeing the text, are often at odds with the apologist tone of the text. The section titled “Crop time, or Gathering the Canes,” for instance, describes the cane harvest as “a season of great mirth and festivity; and so highly nourishing to the bodily frame is the juice of the Cane that every animal derives health and vigour from the use of it. The Negroes that were meagre and sick before, by drinking freely of it, become healthy in a few weeks after the mill is set in action.” The lie that enslaved persons share in the harvest benefits attempts to counter abolitionist accounts of starvation and ignores that enslaved persons worked long hours during harvest and faced dangerous conditions in sugar mills. (A similar depiction of harvest time appears in Cuffy the Negro’s Doggrel Description of the Progress of Sugar.) An accompanying illustration, however, frankly depicts violence. Six black men cut and gather the cane, while two of them look over their shoulder in fear at a black overseer with a whip.

Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar is one of the earliest sugar production stories created for children. Published two years after the abolition of the slave trade in Britain, the book begins by criticizing slavery but ultimately supports its continuation, “for it is now become the interest of the Planter to take more care of his Slaves, to feed them better, and to work them more moderately than he used to do, since he cannot now supply the places of those who die among them, as he could do before the abolition of that wicked Traffic, by the purchase of a fresh parcel, whenever a Slave-ship brought in a Cargo from Africa” (p. 4). Negro Labour shows how the abolition of the slave trade could be used to justify slavery itself. Contrary to the author’s predictions, ending the slave trade did not end overwork, starvation, and torture on plantations. Instead, selling enslaved children became a larger part of the slave plantation economy. The majority of the text focuses on technical details of sugar production, while avoiding overt acknowledgement of slavery or suggesting any political action on the part of readers. Accompanying illustrations, likely crafted without seeing the text, are often at odds with the apologist tone of the text. The section titled “Crop time, or Gathering the Canes,” for instance, describes the cane harvest as “a season of great mirth and festivity; and so highly nourishing to the bodily frame is the juice of the Cane that every animal derives health and vigour from the use of it. The Negroes that were meagre and sick before, by drinking freely of it, become healthy in a few weeks after the mill is set in action.” The lie that enslaved persons share in the harvest benefits attempts to counter abolitionist accounts of starvation and ignores that enslaved persons worked long hours during harvest and faced dangerous conditions in sugar mills. (A similar depiction of harvest time appears in Cuffy the Negro’s Doggrel Description of the Progress of Sugar.) An accompanying illustration, however, frankly depicts violence. Six black men cut and gather the cane, while two of them look over their shoulder in fear at a black overseer with a whip. The Story of Your Coat This first book by Clara Hollos follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Like the Petershams, Hollos offers a global perspective on textiles by following production from wool in Australia to a factory in New York City. The book was published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor and founder of Young World Books, International Publishers’ Children’s Series. Hollos and Kruckman humanize a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Each person involved in making the coat has a names, intelligence, skills, and aspirations. Small portraits of workers and capitalists suggest different races, ethnicities, and cultures for the characters. Kruckman and Bacon both worked at New York City’s Jefferson School of Social Science, a Communist-affiliated institution, where Hollos wrote this story while taking Bacon’s class. Her picturebook pays tribute to the opening anecdote of Marx’s Capital, on how a coat produced by human hands becomes a commodity (Mickenberg and Nel, p. 67). Such a close relationship between production stories and the literature of political economy, trade, and manufacturing began in the early nineteenth-century, when authors of production stories sought to translate the principles of political economy for a mass audience, including children and self-educating adults. The classical political economist Adam Smith and the inventor and manufacturer Charles Babbage used anecdotes about common objects, such as pins or shirts, to illustrate their economic principles, and these same items, featured in children’s textbooks, made abstract concepts into concrete lessons. The codevelopment of children’s production stories with economic writings may explain why textiles such as wool and cotton are among the most common subjects used in both writings. The personal attention given to the different workers appears on every spread, regardless of whether many or few people work together for a given task. The book’s early pages take place on farms and shipyards, where workers learn skills like sheep shearing and wool washing. Their narrative treatment is much the same as for the office and factory workers. Pat the pattern-maker collaboratively works to realize the fashion drawing made by Doris, the designer, before getting approval from Mr. Bing, the factory owner. Likewise, in the Cutting Room, dozens of male workers stand around long tables, drawn with strong diagonal lines that create a sense of energetic motion. The men have easily differentiated features. The text introduces readers to Carl the cutter, along with Hyman, Joe, Tony, Sammy, and Jim, among others, and explains the skill needed to cut wool cloth: “See how carefully Carl does it. It looks easy, but do you really think it is?” On the next spread, the treatment of women in “The Sewing Room” is similar. Dozens of women sew at tables that recede into the distance, filling a large factory floor, yet the first rows present lively faces in detail. The text introduces readers to “Olga, the operator,” mentioned earlier as the elected union representative, who “can make the pieces of cloth whizz under the needle of the sewing machine so fast that you think it must be magic.” Sewers Katie, Myrtle, Sarah, Sonia, Mary each handle a different part of the coat. Their cooperation even extends to Mr. Bing. In addition to paying for materials, Mr. Bing negotiates with the union to decide together how many coats the factory workers can make and how much they will get paid for them. Making coats creates mutual obligations between capitalists, workers, and consumers, with the terms of their social contract renegotiated through collective bargaining. The book’s final pages summarize the coat’s journey from one worker to the next, while a separate page (shown here) summarizes the journey by purchase, from one capitalist to the next: from Mr. Tick, to Mr. Tack, to Mr. Tow, to Mr. Bing, to “Mr. Bang who sold it to you. And now you wear it.” Each person, worker, capitalist, and consumer, has a name and a small color portrait, including a young child at the end, wearing the coat. The right page shows a blue double-breasted wool coat, set off by a vibrant yellow background—an attractive coat that readers may want for themselves. The text on this final page reads: “Your coat was not made by one worker alone. It was not made by one machine alone. It was not made in one place alone. It was made by many workers at different machines in different places—all working together. This is the story of your coat. Do you still think it is just an ordinary coat?” Celebrating global cooperation may seem in line with Hollos’s Marxist politics, but this message is a common one in production stories written by (or expressing) classical capitalist ideas over the last two centuries. Named characters, however, are highly unusual. Hollos rebels against the production story formula in the way she ties together coats with people. Production stories like to promise readers a surprise revelation. But in Hollos’s books, the surprise is how the ordinary becomes extraordinary. While that revelation applies first to the coat, the individualized attention given to the characters makes everyday people just as special.

The Story of Your Coat This first book by Clara Hollos follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Like the Petershams, Hollos offers a global perspective on textiles by following production from wool in Australia to a factory in New York City. The book was published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor and founder of Young World Books, International Publishers’ Children’s Series. Hollos and Kruckman humanize a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Each person involved in making the coat has a names, intelligence, skills, and aspirations. Small portraits of workers and capitalists suggest different races, ethnicities, and cultures for the characters. Kruckman and Bacon both worked at New York City’s Jefferson School of Social Science, a Communist-affiliated institution, where Hollos wrote this story while taking Bacon’s class. Her picturebook pays tribute to the opening anecdote of Marx’s Capital, on how a coat produced by human hands becomes a commodity (Mickenberg and Nel, p. 67). Such a close relationship between production stories and the literature of political economy, trade, and manufacturing began in the early nineteenth-century, when authors of production stories sought to translate the principles of political economy for a mass audience, including children and self-educating adults. The classical political economist Adam Smith and the inventor and manufacturer Charles Babbage used anecdotes about common objects, such as pins or shirts, to illustrate their economic principles, and these same items, featured in children’s textbooks, made abstract concepts into concrete lessons. The codevelopment of children’s production stories with economic writings may explain why textiles such as wool and cotton are among the most common subjects used in both writings. The personal attention given to the different workers appears on every spread, regardless of whether many or few people work together for a given task. The book’s early pages take place on farms and shipyards, where workers learn skills like sheep shearing and wool washing. Their narrative treatment is much the same as for the office and factory workers. Pat the pattern-maker collaboratively works to realize the fashion drawing made by Doris, the designer, before getting approval from Mr. Bing, the factory owner. Likewise, in the Cutting Room, dozens of male workers stand around long tables, drawn with strong diagonal lines that create a sense of energetic motion. The men have easily differentiated features. The text introduces readers to Carl the cutter, along with Hyman, Joe, Tony, Sammy, and Jim, among others, and explains the skill needed to cut wool cloth: “See how carefully Carl does it. It looks easy, but do you really think it is?” On the next spread, the treatment of women in “The Sewing Room” is similar. Dozens of women sew at tables that recede into the distance, filling a large factory floor, yet the first rows present lively faces in detail. The text introduces readers to “Olga, the operator,” mentioned earlier as the elected union representative, who “can make the pieces of cloth whizz under the needle of the sewing machine so fast that you think it must be magic.” Sewers Katie, Myrtle, Sarah, Sonia, Mary each handle a different part of the coat. Their cooperation even extends to Mr. Bing. In addition to paying for materials, Mr. Bing negotiates with the union to decide together how many coats the factory workers can make and how much they will get paid for them. Making coats creates mutual obligations between capitalists, workers, and consumers, with the terms of their social contract renegotiated through collective bargaining. The book’s final pages summarize the coat’s journey from one worker to the next, while a separate page (shown here) summarizes the journey by purchase, from one capitalist to the next: from Mr. Tick, to Mr. Tack, to Mr. Tow, to Mr. Bing, to “Mr. Bang who sold it to you. And now you wear it.” Each person, worker, capitalist, and consumer, has a name and a small color portrait, including a young child at the end, wearing the coat. The right page shows a blue double-breasted wool coat, set off by a vibrant yellow background—an attractive coat that readers may want for themselves. The text on this final page reads: “Your coat was not made by one worker alone. It was not made by one machine alone. It was not made in one place alone. It was made by many workers at different machines in different places—all working together. This is the story of your coat. Do you still think it is just an ordinary coat?” Celebrating global cooperation may seem in line with Hollos’s Marxist politics, but this message is a common one in production stories written by (or expressing) classical capitalist ideas over the last two centuries. Named characters, however, are highly unusual. Hollos rebels against the production story formula in the way she ties together coats with people. Production stories like to promise readers a surprise revelation. But in Hollos’s books, the surprise is how the ordinary becomes extraordinary. While that revelation applies first to the coat, the individualized attention given to the characters makes everyday people just as special. The Story of Your Bread Since the nineteenth-century, many production story series have included a volume on bread, a food that holds symbolic significance in Christian cultures that associate “daily bread” with both holy communion and basic sustenance. This second book on bread by Clara Hollos, published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor at Young world Books, follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Hollos humanizes a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Alongside technological inventions, Hollos describes the social context of production, including slavery, serfdom, and hunger. Illustrations by Lászlo Roth change style to reflect that “people all through the centuries had their own ways of drawing and painting,” as well as their own ways of making bread, the “king of foods.” Unlike her first book on wool coats, The Story of Your Bread offers a global historical survey of bread making, from “the Stone Age to our times,” in which farming and baking are indexes of civilization. This pan-historical approach to production stories takes after some of the earliest production stories. The Arts of Life by John Aiken (1803), for example, argues that technology, cooperation, and government initially arose from the desire to provide for three basic human needs: food, clothing, and shelter. Such production stories recapitulate the story of mankind organized around single commodities (sometimes groups of commodities), creating a progressive history that culminates in the modern, technologically enhanced production of the goods enjoyed by the reader. In production stories, this panhistorical approach often naturalizes the economic dominance of Europeans and European Americans. Nowhere is this more clear than in the final spread of The Story of Your Bread. Four human figures represent different phases in history: “Stone age child,” Egyptian child,” “Roman child,” and “Greek child.” Underneath these, the text states, “And now it give strength to the modern child, who is—YOU,” with a picture of a boy flexing his muscles. Although different races and ethnicities appear in Lászlo’s illustrations, history culminates in the strength of this white male child, who represents the book’s reader and bread eater. Books for younger readers balance a celebration of modern technology with assurances that things will stay the same. In “The Wheat Farm Run by Machinery,” a family farm relies on tractors and modern chemistry, and the farm is flanked by the transportation network that connects agriculture to the city: planes, trains, steamships, and suspension bridges. The farmer’s sons, Butch and Ned, study chemistry at the university, expertise they apply to test the soil and understand what plants will grow. Yet the emphasis on a generational family unit promises readers that farm life will continue from one generation to the next. New modes of communication and transportation will, the image suggests, actually support cultural continuity for families like this one. Similarly, another image of farming families during the harvest features a nostalgic scene of dancing and feasting, juxtaposed with a roadroad map of the US. Again, the modern family of farmers is predominantly European American, suggesting a racially narrow vision of who uses and prospers from new technologies. The book is more inclusive where class is concerned. The image of the large factory where people bake bread, for instance, shows workers with distinct faces and appearances, which gives a sense of individuality. The accompanying text describes the many different kinds of bread that bakeries produce for sale at the store and gives words for bread in different languages. Bread is the “king of foods,” not because only kings eat bread, but because everyone eats bread. Bread can feed large populations and keep them strong: “Most of the world’s work gets done by people who eat bread. They eat a great deal of bread because it is the cheapest of foods and they cannot afford to buy lots of meat and eggs and cheese. The healthiest workers are the ones who eat bread made of whole grains along with other good foods. By eating bread people get the strength they need to do the world’s work.” The page concludes by celebrating farmers for their important work, because they grow “the wheat from which our bread is made.”

The Story of Your Bread Since the nineteenth-century, many production story series have included a volume on bread, a food that holds symbolic significance in Christian cultures that associate “daily bread” with both holy communion and basic sustenance. This second book on bread by Clara Hollos, published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor at Young world Books, follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Hollos humanizes a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Alongside technological inventions, Hollos describes the social context of production, including slavery, serfdom, and hunger. Illustrations by Lászlo Roth change style to reflect that “people all through the centuries had their own ways of drawing and painting,” as well as their own ways of making bread, the “king of foods.” Unlike her first book on wool coats, The Story of Your Bread offers a global historical survey of bread making, from “the Stone Age to our times,” in which farming and baking are indexes of civilization. This pan-historical approach to production stories takes after some of the earliest production stories. The Arts of Life by John Aiken (1803), for example, argues that technology, cooperation, and government initially arose from the desire to provide for three basic human needs: food, clothing, and shelter. Such production stories recapitulate the story of mankind organized around single commodities (sometimes groups of commodities), creating a progressive history that culminates in the modern, technologically enhanced production of the goods enjoyed by the reader. In production stories, this panhistorical approach often naturalizes the economic dominance of Europeans and European Americans. Nowhere is this more clear than in the final spread of The Story of Your Bread. Four human figures represent different phases in history: “Stone age child,” Egyptian child,” “Roman child,” and “Greek child.” Underneath these, the text states, “And now it give strength to the modern child, who is—YOU,” with a picture of a boy flexing his muscles. Although different races and ethnicities appear in Lászlo’s illustrations, history culminates in the strength of this white male child, who represents the book’s reader and bread eater. Books for younger readers balance a celebration of modern technology with assurances that things will stay the same. In “The Wheat Farm Run by Machinery,” a family farm relies on tractors and modern chemistry, and the farm is flanked by the transportation network that connects agriculture to the city: planes, trains, steamships, and suspension bridges. The farmer’s sons, Butch and Ned, study chemistry at the university, expertise they apply to test the soil and understand what plants will grow. Yet the emphasis on a generational family unit promises readers that farm life will continue from one generation to the next. New modes of communication and transportation will, the image suggests, actually support cultural continuity for families like this one. Similarly, another image of farming families during the harvest features a nostalgic scene of dancing and feasting, juxtaposed with a roadroad map of the US. Again, the modern family of farmers is predominantly European American, suggesting a racially narrow vision of who uses and prospers from new technologies. The book is more inclusive where class is concerned. The image of the large factory where people bake bread, for instance, shows workers with distinct faces and appearances, which gives a sense of individuality. The accompanying text describes the many different kinds of bread that bakeries produce for sale at the store and gives words for bread in different languages. Bread is the “king of foods,” not because only kings eat bread, but because everyone eats bread. Bread can feed large populations and keep them strong: “Most of the world’s work gets done by people who eat bread. They eat a great deal of bread because it is the cheapest of foods and they cannot afford to buy lots of meat and eggs and cheese. The healthiest workers are the ones who eat bread made of whole grains along with other good foods. By eating bread people get the strength they need to do the world’s work.” The page concludes by celebrating farmers for their important work, because they grow “the wheat from which our bread is made.” Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Cotton John Wallis printed three production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in a contrived dialect by the fictional character named Cuffy. Recently arrived in London from the West Indies, Cuffy learned how these commodities are made while enslaved, and he promises to tell audiences what he knows. The frontispiece shows the pleasures of consuming these goods, as ladies select cotton cloth for purchase from a smiling salesperson. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons and encourages consumption of cotton products.

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Cotton John Wallis printed three production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in a contrived dialect by the fictional character named Cuffy. Recently arrived in London from the West Indies, Cuffy learned how these commodities are made while enslaved, and he promises to tell audiences what he knows. The frontispiece shows the pleasures of consuming these goods, as ladies select cotton cloth for purchase from a smiling salesperson. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons and encourages consumption of cotton products. Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar Each page of this chapbook features a single illustration depicting one part in the process of making sugar. Readers follow sugar production from slave labor in West Indies plantation cane fields to sugar refineries in British port cities, and finally, to confectioners shops where children purchase sugary treats. John Wallis printed a series of three such production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in contrived dialect and doggerel poetry by the fictional character called Cuffy. Formerly enslaved in the West Indies and recently arrived in London, Cuffy promises to tell audiences what he knows about making these commodities in exchange for coin. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons. Without explicitly supporting slavery, the book effectively defends slavery by depicting work on sugar plantations as so enjoyable that Cuffy regrets leaving. Cane harvesting is a “merry time!” when enslaved persons (denigrated here as livestock) “cut the canes, suck the juice and thrive; / Mule grow fat as hog, though much work he bear-ee; / Horse and cow grow far, starving is no there” (p9). In fact, many enslaved persons starved at harvest time because of the relentless pace of work. The later stages of sugar production in England are shown performed by free white persons. At the conclusion, Cuffy thanks the reader for “kind relief,” or money given to tell his story, directly involving readers in the slave-sugar economy as consumers. The chapbook is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. Yet the racial context of sugar production makes this process take on metaphorical meanings at every turn. Enslaved Africans created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. Sugar production stories used this language of brown, white, and refined, to continually remind readers of constructed racial hierarchies. Moreover, the process of refining sugar required animal blood, or as Cuffy describes: “To make sugar white (sure he be a ninny!) / Blood, and nasty something, baker now put in-ee” (p.15). Beginning in the 1790s, many abolitionist politicians and poets alluded to this fact to make eating slave sugar disgusting. People should boycott sugar, they argued, because slavery is a cannibalistic institution. Since harvesting cane causes the death of overworked, starved enslaved persons, sugar is essentially refined in human blood (See also Sandiford, 2000, p. 124; Sheller, 2003, pp. 88-97). This abolitionist interpretation of the material process—what Timothy Morton calls the “blood sugar topos” (1998, p. 88)—was disseminated so widely that Wallis’s readers may recall this message while reading Cuffy’s account. The image of the “Confectioner,” for instance, shows a plump white man boiling a purple-red liquid in a large pan, suspended over an open stove flame. Although the text describes the liquid as “sugar-plum or candy,” the purple-red coloring may remind readers of human blood. Production stories that condone slavery, such as this one, tend to double-down on the literal, material process of refining sugar, as a way to avoid alluding to the blood sugar topos. This strategy is another example of how production stories can use scientific language to try to avoid addressing social conflict.

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar Each page of this chapbook features a single illustration depicting one part in the process of making sugar. Readers follow sugar production from slave labor in West Indies plantation cane fields to sugar refineries in British port cities, and finally, to confectioners shops where children purchase sugary treats. John Wallis printed a series of three such production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in contrived dialect and doggerel poetry by the fictional character called Cuffy. Formerly enslaved in the West Indies and recently arrived in London, Cuffy promises to tell audiences what he knows about making these commodities in exchange for coin. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons. Without explicitly supporting slavery, the book effectively defends slavery by depicting work on sugar plantations as so enjoyable that Cuffy regrets leaving. Cane harvesting is a “merry time!” when enslaved persons (denigrated here as livestock) “cut the canes, suck the juice and thrive; / Mule grow fat as hog, though much work he bear-ee; / Horse and cow grow far, starving is no there” (p9). In fact, many enslaved persons starved at harvest time because of the relentless pace of work. The later stages of sugar production in England are shown performed by free white persons. At the conclusion, Cuffy thanks the reader for “kind relief,” or money given to tell his story, directly involving readers in the slave-sugar economy as consumers. The chapbook is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. Yet the racial context of sugar production makes this process take on metaphorical meanings at every turn. Enslaved Africans created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. Sugar production stories used this language of brown, white, and refined, to continually remind readers of constructed racial hierarchies. Moreover, the process of refining sugar required animal blood, or as Cuffy describes: “To make sugar white (sure he be a ninny!) / Blood, and nasty something, baker now put in-ee” (p.15). Beginning in the 1790s, many abolitionist politicians and poets alluded to this fact to make eating slave sugar disgusting. People should boycott sugar, they argued, because slavery is a cannibalistic institution. Since harvesting cane causes the death of overworked, starved enslaved persons, sugar is essentially refined in human blood (See also Sandiford, 2000, p. 124; Sheller, 2003, pp. 88-97). This abolitionist interpretation of the material process—what Timothy Morton calls the “blood sugar topos” (1998, p. 88)—was disseminated so widely that Wallis’s readers may recall this message while reading Cuffy’s account. The image of the “Confectioner,” for instance, shows a plump white man boiling a purple-red liquid in a large pan, suspended over an open stove flame. Although the text describes the liquid as “sugar-plum or candy,” the purple-red coloring may remind readers of human blood. Production stories that condone slavery, such as this one, tend to double-down on the literal, material process of refining sugar, as a way to avoid alluding to the blood sugar topos. This strategy is another example of how production stories can use scientific language to try to avoid addressing social conflict.