The items below are analyzed in "The Progress of Sugar: Consumption as Complicity in Children’s Books about Slavery and Manufacturing, 1790-2015," by Elizabeth Massa Hoiem, now available through advanced digital publication in the academic journal Children's Literature in Education (2020). The item descriptions can be read independently and provide visual analysis not covered in the article. For those without journal access, a manuscript of "The Progress of Sugar" is available through IDEALS, the open-source repository for the University of Illinois.

“The Progress of Sugar” examines the historical origins of production stories for children, written in English and published in the United States and Great Britain. During the 18th and 19th C, privileged children and their parents greatly increased their consumption of sugar, coffee, cotton, and rum—all commodities eaten or worn on the body and produced by enslaved persons. To prepare children for this new industrial global economy, parents educated their children about how and where things were made, using a new kind of information book. When writing the story of these commodities, authors of these early economics and manufacturing textbooks had to make ethical choices about whether to disclose to children the human costs behind their clothing and treats. While abolitionists used the production story to expose the horrors of slavery and encourage children to join boycotts or sign petitions, proslavery authors celebrated the pleasures of affordable goods and circulated lies and misrepresentations. Still other authors avoided the subject of slavery altogether by focusing on the science, technology, statistics, and machines used to make these products, to the near exclusion of the people who did the work.

The production story is a result of this troubled history. To this day, the production story tends to cover how things are made separately from who makes things and under what conditions. One aim of this exhibit is to encourage librarians, educators, and readers to look for production stories that faithfully tell the human story behind making things and to recognize when production stories resist the legacies of slavery, resource extraction, and child labor that the genre was once designed to hide.

Books and media analyzed in the article

-

A Fine Dessert: Four Centuries, Four Families A Fine Dessert is a picturebook about four families who make blackberry fool, a fruit and whipped cream dessert. Each family cooks in a different time and place, showing four centuries of cultural change, from Lyme, England (1710), to Charleston, South Carolina (1810), to Boston, Massachusetts (1910), to San Diego, California (2010). A Fine Dessert received positive reviews at its publication, but readers pushed back online by questioning how black children may feel when reading about an enslaved black girl and her mother in Charleston, South Carolina (1810). The two occasionally smile while they work, and they make the desert for a white family, then lick the bowl while hiding in a linen closet (Thomas, Reese, and Horning, 2016, pp. 6-11). Despite the association of sweet treats with innocent children, the history of making and eating desserts is an especially fraught topic. Cheap sugar production drove the rapid spread of black chattel slavery, which served the eating pleasure of white families. As a result, many sugar production stories from the last two centuries have misrepresented sugar slavery to children, to avoid showing the human cost of their favorite treats. This context for sugar stories is important for how readers may feel about a contemporary picturebook on a similar topic. By considering A Fine Dessert as a production story, we can understand how its approach unwittingly relies upon a storytelling tradition originally designed to celebrate technology and hide oppression. First, production stories favor strict repetitive formulas across the full story or series. The production story series by John Wallis (ca. 1805-1840), William Newman (1861-1863), or Maud and Miska Petersham (1930s) treat various commodities, such as bread, coal, steel, diamonds, or sugar, using the same formulaic approach for each one. They often use the same visual layout and descriptive tone, creating an enchantment with mechanical repetition that supports the genre’s underlying narrative of technological progress. The stricter the formula, the more likely that the series creates an inappropriate equivalency between free and enslaved workers. Illustrator Sophie Blackall uses this repetitive approach to enable readers to compare family cuisine between the four time periods—with similar limitations. Second, production stories typically end with children joyously consuming the product in question. This invitation to “join the feast” can distance readers who have social justice concerns about how the product was made. The final spread of A Fine Desert shows a multi-racial, multi-ethnic gathering of friends, eating dessert in San Diego, California (2010)—the present-day parallel of the 1810 image. Although the families are diverse, their emotional responses are not. The final representation of happy children from the present-day US may alienate readers who do not see their feelings acknowledged in these happy faces. The problem of reader identification in the “final feast” also occurs in Clara Hollos’s The Story of Your Bread (1946) and Henry Newman’s The Story of Sugar (1861), both of which feature white children as the final consumers.

A Fine Dessert: Four Centuries, Four Families A Fine Dessert is a picturebook about four families who make blackberry fool, a fruit and whipped cream dessert. Each family cooks in a different time and place, showing four centuries of cultural change, from Lyme, England (1710), to Charleston, South Carolina (1810), to Boston, Massachusetts (1910), to San Diego, California (2010). A Fine Dessert received positive reviews at its publication, but readers pushed back online by questioning how black children may feel when reading about an enslaved black girl and her mother in Charleston, South Carolina (1810). The two occasionally smile while they work, and they make the desert for a white family, then lick the bowl while hiding in a linen closet (Thomas, Reese, and Horning, 2016, pp. 6-11). Despite the association of sweet treats with innocent children, the history of making and eating desserts is an especially fraught topic. Cheap sugar production drove the rapid spread of black chattel slavery, which served the eating pleasure of white families. As a result, many sugar production stories from the last two centuries have misrepresented sugar slavery to children, to avoid showing the human cost of their favorite treats. This context for sugar stories is important for how readers may feel about a contemporary picturebook on a similar topic. By considering A Fine Dessert as a production story, we can understand how its approach unwittingly relies upon a storytelling tradition originally designed to celebrate technology and hide oppression. First, production stories favor strict repetitive formulas across the full story or series. The production story series by John Wallis (ca. 1805-1840), William Newman (1861-1863), or Maud and Miska Petersham (1930s) treat various commodities, such as bread, coal, steel, diamonds, or sugar, using the same formulaic approach for each one. They often use the same visual layout and descriptive tone, creating an enchantment with mechanical repetition that supports the genre’s underlying narrative of technological progress. The stricter the formula, the more likely that the series creates an inappropriate equivalency between free and enslaved workers. Illustrator Sophie Blackall uses this repetitive approach to enable readers to compare family cuisine between the four time periods—with similar limitations. Second, production stories typically end with children joyously consuming the product in question. This invitation to “join the feast” can distance readers who have social justice concerns about how the product was made. The final spread of A Fine Desert shows a multi-racial, multi-ethnic gathering of friends, eating dessert in San Diego, California (2010)—the present-day parallel of the 1810 image. Although the families are diverse, their emotional responses are not. The final representation of happy children from the present-day US may alienate readers who do not see their feelings acknowledged in these happy faces. The problem of reader identification in the “final feast” also occurs in Clara Hollos’s The Story of Your Bread (1946) and Henry Newman’s The Story of Sugar (1861), both of which feature white children as the final consumers. -

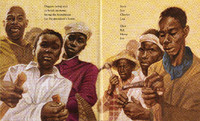

Brick by Brick Brick by Brick tells the story of the people who built the White House (1792-1800), showing cooperation between enslaved and free persons, and between black and white artisans. Production stories about historically significant structures—such as estate houses, castles, bridges, engineering wonders, government buildings, and churches—have their roots in early travel literature for children. By the mid-eighteenth century, educational travel literature included sketches about the major historical landmarks that children might tour with their families, alongside other sites like factories, shipyards, and natural wonders. By the twentieth century, improvements in book illustration and affordable printing supported a resurgence of production stories about buildings, marked by David Macaulay’s Caldecott honor book, Cathedral (1973). The construction industry is not responsible for the expansion of chattel slavery in the same way as cotton or sugar. Yet production stories about buildings remain political because they are symbolically significant embodiments of the narratives people tell about their nation. Emotional investment in old buildings leads to debates over what stories they should reveal for visitors. For instance, plantation houses attract visitors who want to learn accurate information about the lives of enslaved persons, but also visitors who expect a nostalgic reenactment of Antebellum America. Federal monuments celebrate the achievements of early Americans, which include slave owners such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Production stories about major buildings thus have to contend with questions of national identity. And like other production stories, they have always been deeply political, requiring the author to decide whether to reveal to children the possibly violent history of how a building was made and for what purpose. Even the earliest sketches about famous buildings in children’s books touched upon whether the pyramids were built by slaves, or celebrated a famous female general who once defended her castle, or explained religious wars that destroyed a family—historical events that resonated with present-day controversies. Brick by Brick centers more on the people who built the White House than on the building itself. In the first spread shown here, the text suggests names for the unnamed workers. Photorealistic illustrations provide strongly individualized facial expressions that frankly acknowledge the exhaustive work, the participation of enslaved children, and the violence used to coerce enslaved persons. In picture after picture, enslaved black workers meet the reader’s gaze. Some of them look angry, others disheartened, and some hopeful. The mixed expressions heighten reader identification and humanize the many people involved in the work, only some of whom were allowed to keep a portion of their wages, which they used to buy their freedom. When the White House is finished, the illustration focuses on the builders themselves, with the White House itself outside of the frame. For their part, the builders look in several directions, some looking at one another. Centering the people, not the building, is an important authorial choice because so many production stories minimize the faces and identities of people at work, focusing instead on a famous architect or engineering feat. The closest readers get to the White House is in the final spread. A contemporary African American family atop the White House roof tends a flag ambiguously posted at half mast, as if in mourning for those who died without their freedom. The view is difficult to identify, since we are level with the family. One intriguing way to interpret the image is that viewers are looking at this scene from across the National Mall, while standing inside the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which was under construction when Brick by Brick was published. From this perspective, the book mourns and celebrates the construction of two quite different buildings, placed opposite to one another.

Brick by Brick Brick by Brick tells the story of the people who built the White House (1792-1800), showing cooperation between enslaved and free persons, and between black and white artisans. Production stories about historically significant structures—such as estate houses, castles, bridges, engineering wonders, government buildings, and churches—have their roots in early travel literature for children. By the mid-eighteenth century, educational travel literature included sketches about the major historical landmarks that children might tour with their families, alongside other sites like factories, shipyards, and natural wonders. By the twentieth century, improvements in book illustration and affordable printing supported a resurgence of production stories about buildings, marked by David Macaulay’s Caldecott honor book, Cathedral (1973). The construction industry is not responsible for the expansion of chattel slavery in the same way as cotton or sugar. Yet production stories about buildings remain political because they are symbolically significant embodiments of the narratives people tell about their nation. Emotional investment in old buildings leads to debates over what stories they should reveal for visitors. For instance, plantation houses attract visitors who want to learn accurate information about the lives of enslaved persons, but also visitors who expect a nostalgic reenactment of Antebellum America. Federal monuments celebrate the achievements of early Americans, which include slave owners such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Production stories about major buildings thus have to contend with questions of national identity. And like other production stories, they have always been deeply political, requiring the author to decide whether to reveal to children the possibly violent history of how a building was made and for what purpose. Even the earliest sketches about famous buildings in children’s books touched upon whether the pyramids were built by slaves, or celebrated a famous female general who once defended her castle, or explained religious wars that destroyed a family—historical events that resonated with present-day controversies. Brick by Brick centers more on the people who built the White House than on the building itself. In the first spread shown here, the text suggests names for the unnamed workers. Photorealistic illustrations provide strongly individualized facial expressions that frankly acknowledge the exhaustive work, the participation of enslaved children, and the violence used to coerce enslaved persons. In picture after picture, enslaved black workers meet the reader’s gaze. Some of them look angry, others disheartened, and some hopeful. The mixed expressions heighten reader identification and humanize the many people involved in the work, only some of whom were allowed to keep a portion of their wages, which they used to buy their freedom. When the White House is finished, the illustration focuses on the builders themselves, with the White House itself outside of the frame. For their part, the builders look in several directions, some looking at one another. Centering the people, not the building, is an important authorial choice because so many production stories minimize the faces and identities of people at work, focusing instead on a famous architect or engineering feat. The closest readers get to the White House is in the final spread. A contemporary African American family atop the White House roof tends a flag ambiguously posted at half mast, as if in mourning for those who died without their freedom. The view is difficult to identify, since we are level with the family. One intriguing way to interpret the image is that viewers are looking at this scene from across the National Mall, while standing inside the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which was under construction when Brick by Brick was published. From this perspective, the book mourns and celebrates the construction of two quite different buildings, placed opposite to one another. -

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Cotton John Wallis printed three production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in a contrived dialect by the fictional character named Cuffy. Recently arrived in London from the West Indies, Cuffy learned how these commodities are made while enslaved, and he promises to tell audiences what he knows. The frontispiece shows the pleasures of consuming these goods, as ladies select cotton cloth for purchase from a smiling salesperson. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons and encourages consumption of cotton products.

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Cotton John Wallis printed three production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in a contrived dialect by the fictional character named Cuffy. Recently arrived in London from the West Indies, Cuffy learned how these commodities are made while enslaved, and he promises to tell audiences what he knows. The frontispiece shows the pleasures of consuming these goods, as ladies select cotton cloth for purchase from a smiling salesperson. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons and encourages consumption of cotton products. -

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar Each page of this chapbook features a single illustration depicting one part in the process of making sugar. Readers follow sugar production from slave labor in West Indies plantation cane fields to sugar refineries in British port cities, and finally, to confectioners shops where children purchase sugary treats. John Wallis printed a series of three such production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in contrived dialect and doggerel poetry by the fictional character called Cuffy. Formerly enslaved in the West Indies and recently arrived in London, Cuffy promises to tell audiences what he knows about making these commodities in exchange for coin. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons. Without explicitly supporting slavery, the book effectively defends slavery by depicting work on sugar plantations as so enjoyable that Cuffy regrets leaving. Cane harvesting is a “merry time!” when enslaved persons (denigrated here as livestock) “cut the canes, suck the juice and thrive; / Mule grow fat as hog, though much work he bear-ee; / Horse and cow grow far, starving is no there” (p9). In fact, many enslaved persons starved at harvest time because of the relentless pace of work. The later stages of sugar production in England are shown performed by free white persons. At the conclusion, Cuffy thanks the reader for “kind relief,” or money given to tell his story, directly involving readers in the slave-sugar economy as consumers. The chapbook is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. Yet the racial context of sugar production makes this process take on metaphorical meanings at every turn. Enslaved Africans created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. Sugar production stories used this language of brown, white, and refined, to continually remind readers of constructed racial hierarchies. Moreover, the process of refining sugar required animal blood, or as Cuffy describes: “To make sugar white (sure he be a ninny!) / Blood, and nasty something, baker now put in-ee” (p.15). Beginning in the 1790s, many abolitionist politicians and poets alluded to this fact to make eating slave sugar disgusting. People should boycott sugar, they argued, because slavery is a cannibalistic institution. Since harvesting cane causes the death of overworked, starved enslaved persons, sugar is essentially refined in human blood (See also Sandiford, 2000, p. 124; Sheller, 2003, pp. 88-97). This abolitionist interpretation of the material process—what Timothy Morton calls the “blood sugar topos” (1998, p. 88)—was disseminated so widely that Wallis’s readers may recall this message while reading Cuffy’s account. The image of the “Confectioner,” for instance, shows a plump white man boiling a purple-red liquid in a large pan, suspended over an open stove flame. Although the text describes the liquid as “sugar-plum or candy,” the purple-red coloring may remind readers of human blood. Production stories that condone slavery, such as this one, tend to double-down on the literal, material process of refining sugar, as a way to avoid alluding to the blood sugar topos. This strategy is another example of how production stories can use scientific language to try to avoid addressing social conflict.

Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar Each page of this chapbook features a single illustration depicting one part in the process of making sugar. Readers follow sugar production from slave labor in West Indies plantation cane fields to sugar refineries in British port cities, and finally, to confectioners shops where children purchase sugary treats. John Wallis printed a series of three such production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in contrived dialect and doggerel poetry by the fictional character called Cuffy. Formerly enslaved in the West Indies and recently arrived in London, Cuffy promises to tell audiences what he knows about making these commodities in exchange for coin. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons. Without explicitly supporting slavery, the book effectively defends slavery by depicting work on sugar plantations as so enjoyable that Cuffy regrets leaving. Cane harvesting is a “merry time!” when enslaved persons (denigrated here as livestock) “cut the canes, suck the juice and thrive; / Mule grow fat as hog, though much work he bear-ee; / Horse and cow grow far, starving is no there” (p9). In fact, many enslaved persons starved at harvest time because of the relentless pace of work. The later stages of sugar production in England are shown performed by free white persons. At the conclusion, Cuffy thanks the reader for “kind relief,” or money given to tell his story, directly involving readers in the slave-sugar economy as consumers. The chapbook is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. Yet the racial context of sugar production makes this process take on metaphorical meanings at every turn. Enslaved Africans created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. Sugar production stories used this language of brown, white, and refined, to continually remind readers of constructed racial hierarchies. Moreover, the process of refining sugar required animal blood, or as Cuffy describes: “To make sugar white (sure he be a ninny!) / Blood, and nasty something, baker now put in-ee” (p.15). Beginning in the 1790s, many abolitionist politicians and poets alluded to this fact to make eating slave sugar disgusting. People should boycott sugar, they argued, because slavery is a cannibalistic institution. Since harvesting cane causes the death of overworked, starved enslaved persons, sugar is essentially refined in human blood (See also Sandiford, 2000, p. 124; Sheller, 2003, pp. 88-97). This abolitionist interpretation of the material process—what Timothy Morton calls the “blood sugar topos” (1998, p. 88)—was disseminated so widely that Wallis’s readers may recall this message while reading Cuffy’s account. The image of the “Confectioner,” for instance, shows a plump white man boiling a purple-red liquid in a large pan, suspended over an open stove flame. Although the text describes the liquid as “sugar-plum or candy,” the purple-red coloring may remind readers of human blood. Production stories that condone slavery, such as this one, tend to double-down on the literal, material process of refining sugar, as a way to avoid alluding to the blood sugar topos. This strategy is another example of how production stories can use scientific language to try to avoid addressing social conflict. -

Dave the Potter: Poet, Artist, Slave Dave the Potter is one of many contemporary picturebook production stories for children that explain how something was made in the past. Another example is Marguerite Makes a Book by Bruce Robertson, illustrated by Kathryn Hewitt, about a girl who makes an illuminated manuscript; A Fine Dessert by Emily Jenkins, illustrated by Sophie Backall, about making a blackberry and whipped cream treat; and Blacksmith’s Song by Elizabeth Van Steenwyk, illustrated by Anna Rich, about the son of an enslaved blacksmith, who assists his father in the forge and helps freedom seekers. Picturebooks about making things in the past are either told from the perspective of a child who learns how to make something, or they are exemplary biographies of famous artists, musicians, and artisans. Dave the Potter tells the biography of David Drake, an enslaved master potter responsible for managing the operations of a pottery manufactory in the Edgefield District of South Carolina. Based on the latest designs, his industrial sized kiln made massive pots used to store grain and salted meats to feed the growing regional population of enslaved persons. The picturebook thus engages with both ceramics and basic food supplies, both commodities often treated in production books. David Drake signed many of his pots “Dave,” adding short poems of rhymed couplets, even though it was against the law for an enslaved person to read or write. Today, his creations are collected in museums for public viewing (Chaney, 2018). The picturebook shows how Dave makes his pots and his poems but avoids erasing his personality and skills by balancing close-ups on Dave’s hands with meditative images of Dave’s face and creative productions. The quadriptych close-ups on Dave’s hands, for instance, which appears mid-book, showcases his craft expertise. Like Dave, readers pull out the book’s page to view the full spread, just as Dave “pulls” his pot from the pottery wheel. Another spread from two pages later shows Dave’s face, with eyes closed, hands thrown wide like Christ to embrace readers, while behind him the faces of Dave’s people stretch out from his mind like an ancestral tree. In both cases, Dave’s creativity is connected to a long history of African Diaspora cultures, that embraces his ancestors but also readers. By involving readers in Dave’s creative enterprise, the picturebook time slips between present-day readers, Dave’s work in the kiln, and Dave’s own past. This Afrofuturist approach brings recipients of David Drake’s art, including readers, to his South Carolina shores, where they can positively identify with his creative spirit but cannot forget the tragedy of his captivity. The picturebook’s multi-temporal setting is doubly fitting because of what Dave writes on this particular pot, which readers only learn on the final spread: “I wonder where / is all my relation / friendship to all— / and, every nation.” Having read Dave’s poetry, readers can turn back time themselves, by turning back the pages of the book, to find the same sentiments foreshadowed on the opening spread: a large pot transposed on a dark Atlantic Ocean, where a single ship recalls the middle passage. Instead of the sky above, viewers look down into the pot’s stored contents, the brown rim of the pot arching like a rainbow’s promise. Remembrance and hope, sealed away, opened later. Perhaps these are the images in Dave’s mind as he made this pot, wondering about “all my relation.”

Dave the Potter: Poet, Artist, Slave Dave the Potter is one of many contemporary picturebook production stories for children that explain how something was made in the past. Another example is Marguerite Makes a Book by Bruce Robertson, illustrated by Kathryn Hewitt, about a girl who makes an illuminated manuscript; A Fine Dessert by Emily Jenkins, illustrated by Sophie Backall, about making a blackberry and whipped cream treat; and Blacksmith’s Song by Elizabeth Van Steenwyk, illustrated by Anna Rich, about the son of an enslaved blacksmith, who assists his father in the forge and helps freedom seekers. Picturebooks about making things in the past are either told from the perspective of a child who learns how to make something, or they are exemplary biographies of famous artists, musicians, and artisans. Dave the Potter tells the biography of David Drake, an enslaved master potter responsible for managing the operations of a pottery manufactory in the Edgefield District of South Carolina. Based on the latest designs, his industrial sized kiln made massive pots used to store grain and salted meats to feed the growing regional population of enslaved persons. The picturebook thus engages with both ceramics and basic food supplies, both commodities often treated in production books. David Drake signed many of his pots “Dave,” adding short poems of rhymed couplets, even though it was against the law for an enslaved person to read or write. Today, his creations are collected in museums for public viewing (Chaney, 2018). The picturebook shows how Dave makes his pots and his poems but avoids erasing his personality and skills by balancing close-ups on Dave’s hands with meditative images of Dave’s face and creative productions. The quadriptych close-ups on Dave’s hands, for instance, which appears mid-book, showcases his craft expertise. Like Dave, readers pull out the book’s page to view the full spread, just as Dave “pulls” his pot from the pottery wheel. Another spread from two pages later shows Dave’s face, with eyes closed, hands thrown wide like Christ to embrace readers, while behind him the faces of Dave’s people stretch out from his mind like an ancestral tree. In both cases, Dave’s creativity is connected to a long history of African Diaspora cultures, that embraces his ancestors but also readers. By involving readers in Dave’s creative enterprise, the picturebook time slips between present-day readers, Dave’s work in the kiln, and Dave’s own past. This Afrofuturist approach brings recipients of David Drake’s art, including readers, to his South Carolina shores, where they can positively identify with his creative spirit but cannot forget the tragedy of his captivity. The picturebook’s multi-temporal setting is doubly fitting because of what Dave writes on this particular pot, which readers only learn on the final spread: “I wonder where / is all my relation / friendship to all— / and, every nation.” Having read Dave’s poetry, readers can turn back time themselves, by turning back the pages of the book, to find the same sentiments foreshadowed on the opening spread: a large pot transposed on a dark Atlantic Ocean, where a single ship recalls the middle passage. Instead of the sky above, viewers look down into the pot’s stored contents, the brown rim of the pot arching like a rainbow’s promise. Remembrance and hope, sealed away, opened later. Perhaps these are the images in Dave’s mind as he made this pot, wondering about “all my relation.” -

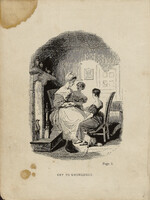

Key to Knowledge, or, Things in Common Use: Simply and Shortly Explained in a Series of Dialogues Key to Knowledge is a kind of production story textbook once popular during the nineteenth century, featuring an exemplary adult teacher, who has lively conversations with a young family. The story follows the day-to-day activities of the children, while they eat breakfast, explore the outdoors with walks, and visit artisan shops or factories. Accompanying the children on their exclusions, the beloved parent or family friend (a mother, in this case) answers the children’s questions and encourages their curiosity and powers of observation. The goal of such books was to model for children how to learn in the regular course of their lives. The child characters model how to consult adult science books to learn more about what interests them, and they report their findings to the family with oral reports, science demonstrations, essays, letters, and other creative activities. As a result, a book like this one contains long passages of material excerpted from adult nonfiction and adapted for child readers, in the voice of the characters. At the time these were written, many wealthy families educated their children at home, through parents, tutors, and governesses. Children and parents who read A Key to Knowledge are expected to form their own educational experiences after the actions of these characters. The mode of education modeled by the book emphasizes active learning, experimentation, and conversation, over traditional book learning. Over the course of the nineteenth-century, books like this one began targeting girls or boys, indicated by the genders of the sibling characters. Aunt Martha’s Cupboard shows the typical formula for a girls’ textbook. Aunt Martha teaches the sisters about manufacturing by exploring items in the home, which connects their domestic environment to global trade. Like other middle-class families, they drink tea with sugar, which prompts the lesson on sugar production, including the images shown here.

Key to Knowledge, or, Things in Common Use: Simply and Shortly Explained in a Series of Dialogues Key to Knowledge is a kind of production story textbook once popular during the nineteenth century, featuring an exemplary adult teacher, who has lively conversations with a young family. The story follows the day-to-day activities of the children, while they eat breakfast, explore the outdoors with walks, and visit artisan shops or factories. Accompanying the children on their exclusions, the beloved parent or family friend (a mother, in this case) answers the children’s questions and encourages their curiosity and powers of observation. The goal of such books was to model for children how to learn in the regular course of their lives. The child characters model how to consult adult science books to learn more about what interests them, and they report their findings to the family with oral reports, science demonstrations, essays, letters, and other creative activities. As a result, a book like this one contains long passages of material excerpted from adult nonfiction and adapted for child readers, in the voice of the characters. At the time these were written, many wealthy families educated their children at home, through parents, tutors, and governesses. Children and parents who read A Key to Knowledge are expected to form their own educational experiences after the actions of these characters. The mode of education modeled by the book emphasizes active learning, experimentation, and conversation, over traditional book learning. Over the course of the nineteenth-century, books like this one began targeting girls or boys, indicated by the genders of the sibling characters. Aunt Martha’s Cupboard shows the typical formula for a girls’ textbook. Aunt Martha teaches the sisters about manufacturing by exploring items in the home, which connects their domestic environment to global trade. Like other middle-class families, they drink tea with sugar, which prompts the lesson on sugar production, including the images shown here. -

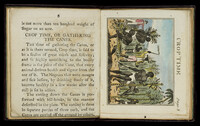

Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar is one of the earliest sugar production stories created for children. Published two years after the abolition of the slave trade in Britain, the book begins by criticizing slavery but ultimately supports its continuation, “for it is now become the interest of the Planter to take more care of his Slaves, to feed them better, and to work them more moderately than he used to do, since he cannot now supply the places of those who die among them, as he could do before the abolition of that wicked Traffic, by the purchase of a fresh parcel, whenever a Slave-ship brought in a Cargo from Africa” (p. 4). Negro Labour shows how the abolition of the slave trade could be used to justify slavery itself. Contrary to the author’s predictions, ending the slave trade did not end overwork, starvation, and torture on plantations. Instead, selling enslaved children became a larger part of the slave plantation economy. The majority of the text focuses on technical details of sugar production, while avoiding overt acknowledgement of slavery or suggesting any political action on the part of readers. Accompanying illustrations, likely crafted without seeing the text, are often at odds with the apologist tone of the text. The section titled “Crop time, or Gathering the Canes,” for instance, describes the cane harvest as “a season of great mirth and festivity; and so highly nourishing to the bodily frame is the juice of the Cane that every animal derives health and vigour from the use of it. The Negroes that were meagre and sick before, by drinking freely of it, become healthy in a few weeks after the mill is set in action.” The lie that enslaved persons share in the harvest benefits attempts to counter abolitionist accounts of starvation and ignores that enslaved persons worked long hours during harvest and faced dangerous conditions in sugar mills. (A similar depiction of harvest time appears in Cuffy the Negro’s Doggrel Description of the Progress of Sugar.) An accompanying illustration, however, frankly depicts violence. Six black men cut and gather the cane, while two of them look over their shoulder in fear at a black overseer with a whip.

Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar Negro Labour, or The Progress of Sugar is one of the earliest sugar production stories created for children. Published two years after the abolition of the slave trade in Britain, the book begins by criticizing slavery but ultimately supports its continuation, “for it is now become the interest of the Planter to take more care of his Slaves, to feed them better, and to work them more moderately than he used to do, since he cannot now supply the places of those who die among them, as he could do before the abolition of that wicked Traffic, by the purchase of a fresh parcel, whenever a Slave-ship brought in a Cargo from Africa” (p. 4). Negro Labour shows how the abolition of the slave trade could be used to justify slavery itself. Contrary to the author’s predictions, ending the slave trade did not end overwork, starvation, and torture on plantations. Instead, selling enslaved children became a larger part of the slave plantation economy. The majority of the text focuses on technical details of sugar production, while avoiding overt acknowledgement of slavery or suggesting any political action on the part of readers. Accompanying illustrations, likely crafted without seeing the text, are often at odds with the apologist tone of the text. The section titled “Crop time, or Gathering the Canes,” for instance, describes the cane harvest as “a season of great mirth and festivity; and so highly nourishing to the bodily frame is the juice of the Cane that every animal derives health and vigour from the use of it. The Negroes that were meagre and sick before, by drinking freely of it, become healthy in a few weeks after the mill is set in action.” The lie that enslaved persons share in the harvest benefits attempts to counter abolitionist accounts of starvation and ignores that enslaved persons worked long hours during harvest and faced dangerous conditions in sugar mills. (A similar depiction of harvest time appears in Cuffy the Negro’s Doggrel Description of the Progress of Sugar.) An accompanying illustration, however, frankly depicts violence. Six black men cut and gather the cane, while two of them look over their shoulder in fear at a black overseer with a whip. -

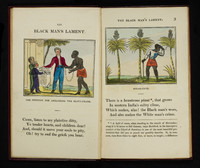

The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar One of the earliest abolitionist books for children, this production story by the Quaker abolitionist novelist and poet, Amelia Alderson Opie is a call to political action that eschews the pleasures of consumption. The copperplate engravings are by an unknown artist, but the style indicates that children’s publishers Harvey and Darton, a prominent abolitionist and Quaker firm, used the same artist for their reprint of William Cowper’s “The Negro’s Complaint” (Cutter, p. 71). According to historian Martha Cutter, the illustrator takes care to represent “distinctive (rather than stereotypical) persons,” who allow for intersubjectivity by meeting the viewer’s gaze (p. 82). Opie adapts the production story formula to foreground her abolitionist message, by opening her story with a plea to readers “to end the griefs you hear (p.2). The opening illustration shows two children signing a petition in support of abolition of the slave trade. A man in chains on the right resembles Wedgewood’s often circulated abolitionist image of a supplicant slave, but rather than kneeling, he stands and reaches out to the children. The right-hand page introduces sugar cane as a “beauteous plant” that “makes, alas! The Blank man’s woes, / And also makes the White man’s crimes,” with a lengthy small print footnote on sugar cane’s appearance and cultivation (p. 3). Readers accustomed to the scientific language of production stories would be surprised to find the actual process of sugar making relegated to the footnotes. Again, on the next spread, technical detail that would usually occupy a prominent place remains peripheral, while the emotional appeal of a human story dominates (p. 4). At this moment in the story, the enslaved man takes over narration until its conclusion. The accompanying illustration shows him “torn” from his wife and infant by men wielding swords and cudgels (p. 5). Some of the images, such as “Cutting Down the Sugar-Cane” and “The Bruising-Mill” (pp. 16-17) closely resemble those provided in other sugar production narratives, such as Negro Labour (1809) or William Newman’s A History of a Pound of Sugar (1861). This conformity to generic expectations makes the unique text below the images all the more striking. Harvest time is usually portrayed in sugar production narratives as a joyous, healthful time when harvesters gain weight by chewing the ends of cut cane. But in a departure from this formula, Opie’s speaker describes harvest as the beginning of “our saddest pains; / For then we toil both day and night.” Instead of feeding themselves, they feed an ever-hungry grinding mill.

The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar One of the earliest abolitionist books for children, this production story by the Quaker abolitionist novelist and poet, Amelia Alderson Opie is a call to political action that eschews the pleasures of consumption. The copperplate engravings are by an unknown artist, but the style indicates that children’s publishers Harvey and Darton, a prominent abolitionist and Quaker firm, used the same artist for their reprint of William Cowper’s “The Negro’s Complaint” (Cutter, p. 71). According to historian Martha Cutter, the illustrator takes care to represent “distinctive (rather than stereotypical) persons,” who allow for intersubjectivity by meeting the viewer’s gaze (p. 82). Opie adapts the production story formula to foreground her abolitionist message, by opening her story with a plea to readers “to end the griefs you hear (p.2). The opening illustration shows two children signing a petition in support of abolition of the slave trade. A man in chains on the right resembles Wedgewood’s often circulated abolitionist image of a supplicant slave, but rather than kneeling, he stands and reaches out to the children. The right-hand page introduces sugar cane as a “beauteous plant” that “makes, alas! The Blank man’s woes, / And also makes the White man’s crimes,” with a lengthy small print footnote on sugar cane’s appearance and cultivation (p. 3). Readers accustomed to the scientific language of production stories would be surprised to find the actual process of sugar making relegated to the footnotes. Again, on the next spread, technical detail that would usually occupy a prominent place remains peripheral, while the emotional appeal of a human story dominates (p. 4). At this moment in the story, the enslaved man takes over narration until its conclusion. The accompanying illustration shows him “torn” from his wife and infant by men wielding swords and cudgels (p. 5). Some of the images, such as “Cutting Down the Sugar-Cane” and “The Bruising-Mill” (pp. 16-17) closely resemble those provided in other sugar production narratives, such as Negro Labour (1809) or William Newman’s A History of a Pound of Sugar (1861). This conformity to generic expectations makes the unique text below the images all the more striking. Harvest time is usually portrayed in sugar production narratives as a joyous, healthful time when harvesters gain weight by chewing the ends of cut cane. But in a departure from this formula, Opie’s speaker describes harvest as the beginning of “our saddest pains; / For then we toil both day and night.” Instead of feeding themselves, they feed an ever-hungry grinding mill. -

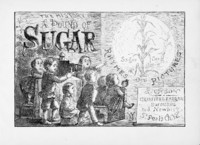

The History of a Pound of Sugar William Newman wrote a production story series on bread, tea, sugar, coals, and cotton, each printed separately or available together in a single volume. At the date of publication, slavery had ended in the British West Indies but not in the US, where the Civil War had just begun. This volume on sugar begins, on the title page, with white English children eagerly consuming information about sugar cane, delivered in the medium of a magic lantern show, and it ends with white English children eating sugar from a barrel outside of a general store. Creating parallels between these two acts of consumption equates reading with eating and asks readers to identify with the privileged position of white English child consumers. The children operate the magic lantern show themselves. Such visual control over the entire sugar-making process appears throughout the book. The spread showing “Planting,” for instance, is focalized through the perspective of the “Planter,” who “walks around / With eagle glance, and all controls” (p.3). Production stories like this one give children a visual “survey” of the process, using visual strategies such as the elevated view, that give a sense of ownership and control. As a result, child readers are asked to identify with positions of power, such as managers and overseers, rather than with characters performing physical labor or working with machines. The book is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. But the process of refining sugar from brown sugar to white gives the text an opportunity to drive home racial hierarchies to readers. At this time, black workers, often slaves, created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. The description of this process passes judgment on the people who work the sugar at various stages: ‘Safe on our shores; the Sugar still / Is only “Raw,” or unrefined: / This is called “Moist.” The Baker’s skill, / With fire and various aids combined, / Makes of it “Lump”—crisp, crystal white, / Sweet to the taste, and fair to sight’ (p. 10). Such racist comments on the superiority of whiteness are commonplace in nineteenth-century sugar production stories. The cover’s portrayal of other mediated versions of this story suggests that publishers Griffith & Farran may have produced additional learning aids to accompany Newman’s books, such as magic lantern slides, games, or prints to hand on walls. Selling different mediums to teach this material was a strategy used by early-nineteenth-century publisher John Wallis.

The History of a Pound of Sugar William Newman wrote a production story series on bread, tea, sugar, coals, and cotton, each printed separately or available together in a single volume. At the date of publication, slavery had ended in the British West Indies but not in the US, where the Civil War had just begun. This volume on sugar begins, on the title page, with white English children eagerly consuming information about sugar cane, delivered in the medium of a magic lantern show, and it ends with white English children eating sugar from a barrel outside of a general store. Creating parallels between these two acts of consumption equates reading with eating and asks readers to identify with the privileged position of white English child consumers. The children operate the magic lantern show themselves. Such visual control over the entire sugar-making process appears throughout the book. The spread showing “Planting,” for instance, is focalized through the perspective of the “Planter,” who “walks around / With eagle glance, and all controls” (p.3). Production stories like this one give children a visual “survey” of the process, using visual strategies such as the elevated view, that give a sense of ownership and control. As a result, child readers are asked to identify with positions of power, such as managers and overseers, rather than with characters performing physical labor or working with machines. The book is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. But the process of refining sugar from brown sugar to white gives the text an opportunity to drive home racial hierarchies to readers. At this time, black workers, often slaves, created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. The description of this process passes judgment on the people who work the sugar at various stages: ‘Safe on our shores; the Sugar still / Is only “Raw,” or unrefined: / This is called “Moist.” The Baker’s skill, / With fire and various aids combined, / Makes of it “Lump”—crisp, crystal white, / Sweet to the taste, and fair to sight’ (p. 10). Such racist comments on the superiority of whiteness are commonplace in nineteenth-century sugar production stories. The cover’s portrayal of other mediated versions of this story suggests that publishers Griffith & Farran may have produced additional learning aids to accompany Newman’s books, such as magic lantern slides, games, or prints to hand on walls. Selling different mediums to teach this material was a strategy used by early-nineteenth-century publisher John Wallis. -

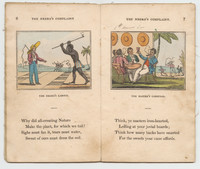

The Negro’s Complaint: A Poem. To Which Is Added, Pity for Poor Africans During the initial rise of the sugar boycotts in Britain, Cooper’s two poems were first printed and widely distributed in 1788 by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. They are not production stories. Nevertheless, this reprint edition by children’s publishers Harvey and Darton uses popular generic conventions for teaching children about commodities. “The Negro’s Complaint” uses the same visual layout as contemporaneous production stories by Opie and Wallis, with a titled illustration and poetry stanzas underneath. One spread shows enslaved Africans planting sugar cane in square holes (p. 6), an illustration nearly identical to those of other sugar production stories (e.g. William Newman, A history of a Pound of Sugar, p. 3). Drawing further parallels, Harvey and Darton used the same illustrator as Amelia Alderson Opie’s The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar, a sugar production story they published the same year. Because of these editorial choices, Cooper’s poem takes on a new meaning for readers familiar with the production story form. Harvey and Darton draw comparisons between production stories and slave autobiographies, two forms that share narrative similarities. The titles of production stories (e.g. The Progress of Cotton; The Story of Sugar) make a commodity into a protagonist (e.g. sugar, cotton, coal), as if children are reading the commodity’s autobiography, and in fact, some fantastical production stories have commodities that come to life and speak their own life histories to human audiences. Autobiographies of former slaves, on the other hand, feature protagonists who were dehumanized as commodities for trade. When Cooper’s narrator, a fictional enslaved African, tells his own story, he follows in this tradition of abolitionist autobiographies. With their editorial choices, Harvey and Darton question why some production stories give agency to personified commodities while dehumanizing the enslaved persons forced to make them. Readers familiar with production story conventions would recognize other places where this book plays with the form. The illustration titled “The Master’s Carousal” positions a standard illustration for the cane harvest in the background, in order to focus, instead, on the “jovial” masters drinking and smoking in the foreground. Readers must confront the “iron-hearted” white men, who drink rum and smoke tobacco, and feel shame that they, too, have enjoyed commodities made by enslaved persons. The second poem in the collection, “Pity for Poor Africans,” has no illustrations, but its effect relies on familiarity with another popular children’s literature genre: the moral tale. The narrator is an Englishman who justifies eating sugar because a boycott would be ineffective, since others eat sugar anyway. He compares his choice to a boy who steals apples from an orchard, after he fails to convince his friends to abstain. Readers familiar with moral tales that warn boys not to steal apples would immediate recognize the speaker’s sophistry, then reevaluate their own choices on sugar consumption. The selection of both poems together suggests that Harvey and Darton considered how to frame abolitionist messages to speak to children, using literary conventions familiar to them.

The Negro’s Complaint: A Poem. To Which Is Added, Pity for Poor Africans During the initial rise of the sugar boycotts in Britain, Cooper’s two poems were first printed and widely distributed in 1788 by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. They are not production stories. Nevertheless, this reprint edition by children’s publishers Harvey and Darton uses popular generic conventions for teaching children about commodities. “The Negro’s Complaint” uses the same visual layout as contemporaneous production stories by Opie and Wallis, with a titled illustration and poetry stanzas underneath. One spread shows enslaved Africans planting sugar cane in square holes (p. 6), an illustration nearly identical to those of other sugar production stories (e.g. William Newman, A history of a Pound of Sugar, p. 3). Drawing further parallels, Harvey and Darton used the same illustrator as Amelia Alderson Opie’s The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar, a sugar production story they published the same year. Because of these editorial choices, Cooper’s poem takes on a new meaning for readers familiar with the production story form. Harvey and Darton draw comparisons between production stories and slave autobiographies, two forms that share narrative similarities. The titles of production stories (e.g. The Progress of Cotton; The Story of Sugar) make a commodity into a protagonist (e.g. sugar, cotton, coal), as if children are reading the commodity’s autobiography, and in fact, some fantastical production stories have commodities that come to life and speak their own life histories to human audiences. Autobiographies of former slaves, on the other hand, feature protagonists who were dehumanized as commodities for trade. When Cooper’s narrator, a fictional enslaved African, tells his own story, he follows in this tradition of abolitionist autobiographies. With their editorial choices, Harvey and Darton question why some production stories give agency to personified commodities while dehumanizing the enslaved persons forced to make them. Readers familiar with production story conventions would recognize other places where this book plays with the form. The illustration titled “The Master’s Carousal” positions a standard illustration for the cane harvest in the background, in order to focus, instead, on the “jovial” masters drinking and smoking in the foreground. Readers must confront the “iron-hearted” white men, who drink rum and smoke tobacco, and feel shame that they, too, have enjoyed commodities made by enslaved persons. The second poem in the collection, “Pity for Poor Africans,” has no illustrations, but its effect relies on familiarity with another popular children’s literature genre: the moral tale. The narrator is an Englishman who justifies eating sugar because a boycott would be ineffective, since others eat sugar anyway. He compares his choice to a boy who steals apples from an orchard, after he fails to convince his friends to abstain. Readers familiar with moral tales that warn boys not to steal apples would immediate recognize the speaker’s sophistry, then reevaluate their own choices on sugar consumption. The selection of both poems together suggests that Harvey and Darton considered how to frame abolitionist messages to speak to children, using literary conventions familiar to them. -

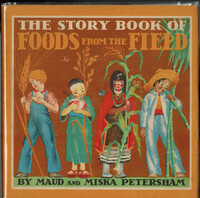

The Story Book of Foods from the Field: Wheat, Corn, Rice, Sugar During the interwar period, author-illustrator team Maud and Miska Petersham created some of the most memorable fiction stories and textbooks for children. With publishers’ renewed interest in children’s books about everyday life, the production story genre was revived in the United States with a series by Janet Smalley, closely followed by the Petersham’s comprehensive series comprised of five schoolbooks: The Story Book of The Things We Use (1933), about houses, food, and transportation; The Story Book of Earth’s Treasures (1935), about gold, coal, oil, iron, and steel; The Story Book of Wheels, Ships, Trains, Aircraft (1935); The Story Book of Foods from the Field (1936), about wheat, corn, rice, sugar; and The Story Book of Things We Wear (1939), about wool, cotton, silk, and rayon. Each of these five covered several commodities that could be purchased as separate volumes (Bader, 93-97). For instance, Foods from the Field includes material on sugar that also appears, with expanded content, in The Storybook of Sugar (1936). The Petersham volume on food thematizes the universal enjoyment of the fruits of the field, captured by the four figures of different cultural and racial appearances on the cover. Production stories favor repetitive formulas, both in text and image, that allow young readers to make interesting comparisons across different time periods, global locations, and human cultures. This cover’s multicultural message helps readers to reflect on our shared humanity, as all people must nourish their bodies with basic food. However, the cane figure placed next to the others also creates equivalency between families whose food access and fair wages may greatly differ. In practice, not all families are allowed to enjoy the products they work to produce, or conversely, families may have limited diets as a result of growing cash crops. A similar tension between the insensitivity of such comparisons and a desire for diverse representation or multicultural perspectives occurs in other production stories. The dust jacket for The Story Book of Foods from the Field shows a child with brown skin chewing cane. The same figure of a cane harvester chewing the cane appears in sugar production stories over the past two hundred years, changing to represent the labor force primarily responsible for sugar production, from enslaved Africans to free workers of different races and ethnicities. One possible cultural function of this perennial figure is to offer a cheerful veneer over questionable labor practices. Such an image reassures privileged consumers who purchase and eat sugar far away from where cane is grown that children involved in the sugar labor force have plenty of food—indeed, they enjoy treats, just like children everywhere. For more information on this figure, see The Story Book of Sugar.

The Story Book of Foods from the Field: Wheat, Corn, Rice, Sugar During the interwar period, author-illustrator team Maud and Miska Petersham created some of the most memorable fiction stories and textbooks for children. With publishers’ renewed interest in children’s books about everyday life, the production story genre was revived in the United States with a series by Janet Smalley, closely followed by the Petersham’s comprehensive series comprised of five schoolbooks: The Story Book of The Things We Use (1933), about houses, food, and transportation; The Story Book of Earth’s Treasures (1935), about gold, coal, oil, iron, and steel; The Story Book of Wheels, Ships, Trains, Aircraft (1935); The Story Book of Foods from the Field (1936), about wheat, corn, rice, sugar; and The Story Book of Things We Wear (1939), about wool, cotton, silk, and rayon. Each of these five covered several commodities that could be purchased as separate volumes (Bader, 93-97). For instance, Foods from the Field includes material on sugar that also appears, with expanded content, in The Storybook of Sugar (1936). The Petersham volume on food thematizes the universal enjoyment of the fruits of the field, captured by the four figures of different cultural and racial appearances on the cover. Production stories favor repetitive formulas, both in text and image, that allow young readers to make interesting comparisons across different time periods, global locations, and human cultures. This cover’s multicultural message helps readers to reflect on our shared humanity, as all people must nourish their bodies with basic food. However, the cane figure placed next to the others also creates equivalency between families whose food access and fair wages may greatly differ. In practice, not all families are allowed to enjoy the products they work to produce, or conversely, families may have limited diets as a result of growing cash crops. A similar tension between the insensitivity of such comparisons and a desire for diverse representation or multicultural perspectives occurs in other production stories. The dust jacket for The Story Book of Foods from the Field shows a child with brown skin chewing cane. The same figure of a cane harvester chewing the cane appears in sugar production stories over the past two hundred years, changing to represent the labor force primarily responsible for sugar production, from enslaved Africans to free workers of different races and ethnicities. One possible cultural function of this perennial figure is to offer a cheerful veneer over questionable labor practices. Such an image reassures privileged consumers who purchase and eat sugar far away from where cane is grown that children involved in the sugar labor force have plenty of food—indeed, they enjoy treats, just like children everywhere. For more information on this figure, see The Story Book of Sugar. -

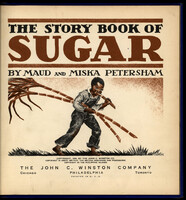

The Story Book of Sugar During the interwar period, author-illustrator team Maud and Miska Petersham created some of the most memorable fiction stories and textbooks for children. With publishers’ renewed interest in children’s books about everyday life, the production story genre was revived in the US with a series by Janet Smalley, closely followed by the Petersham’s comprehensive series comprised of five textbooks: The Story Book of The Things We Use (1933), about houses, food, and transportation; The Story Book of Earth’s Treasures (1935), about gold, coal, oil, iron, and steel; The Story Book of Wheels, Ships, Trains, Aircraft (1935); The Story Book of Foods from the Field (1936), about wheat, corn, rice, sugar; and The Story Book of Things We Wear (1939), about wool, cotton, silk, and rayon. Each of these five contain sections on different commodities that could be purchased as separate volumes. Most of the contents from The Storybook of Sugar (1936) also appear in the volume Foods from the Field (Bader, 93-97). This way of organizing a series by related commodities follows the same marketing strategy used by John Wallis, over a hundred years earlier. The title page for The Story Book of Sugar features a black child chewing cane. Another child chewing cane appears on the dust jacket for The Story Book of Foods from the Field. And a similar boy appears in the corner of an image depicting the cane harvest, titled “In the Sugar-Cane Field.” This cane harvester, chewing cut cane, has a long history. The figure appears in sugar production stories over the past two hundred years, changing to represent the labor force primarily responsible for sugar production, from enslaved Africans to free workers of different races and ethnicities. What is this figure’s perennial appeal? One possibility is that the harvester chewing cane encourages readers’ empathy without challenging their privilege: The image reassures privileged consumers who purchase and eat sugar far away from where cane is grown that children involved in the sugar labor force have plenty of food—indeed, they enjoy treats, just like children everywhere. While encouraging readers to sympathize with producers, such images also spread a cheerful veneer over questionable labor practices. In earlier production stories, the cane chewing figure originated with proslavery literature, which depicted slaves eating cane during harvest to contradict accounts of starvation in cane fields. However, the Petershams partially transform the image by making the cane chewer a child who meets the reader’s gaze. They also feature children eating grains in each segment of The Foods of the Field, where they eat bread, rice, and corn. This suggests that the Petershams are combining two visual tropes: the cane chewing harvester with the child consumer (who generally appears on the final spread of production stories, see for e.g. Hollos’s books). The Storybook of Sugar covers different sweeteners: honey, cane sugar, beet sugar, and maple syrup. Despite this global perspective on sweets, The Story Book of Sugar credits European ingenuity for sugar’s development by focalizing the story through white characters. For instance, the text acknowledges that mass cultivation of sugarcane began in India, yet readers learn about this fact from the perspective of Alexander’s soldier. The tall, armored man dominates the page, as a strong but relatively friendly figure, who “discovers” sugar during an invasion of regions that are now parts of Pakistan and India. Likewise, the section on Spanish sugar cane credits a “negro boy” sent to “the Brothers of the Jesuit Monastery in New Orleans” with figuring out how to cultivate cane, but the text glosses over the child’s enslavement by grouping him with the plants: “Again plants were sent to the Brothers in New Orleans. This time a Negro boy, who knew how to care for them, was sent with them.” The accompanying illustration positions the Spanish overseer in the foreground, his back to readers, which invites viewers to survey the sugar cane plantation from his perspective. The image includes enslaved persons, their bodies bent in labor, but signs of violence and coercion are downplayed. The modern refinery in the final spread captures another visual convention of production stories: the love of modern technology. Factory scenes usually make machinery the star, using repetition to create aesthetic appeal. Wondrous machines draw the viewer’s eye. We admire their size and strength, while human operators seem small and unimportant. In production stories, workers may appear as disembodied hands, or as nearly unrecognizable figures on a massive factory floor. (For a contrasting approach, see the recognizable faces in The Story of Your Coat.) In historical surveys of sugar production, machines capture the imagination after the abolition of slavery in the United States, and texts may even praise machines as “slaves,” as if modern factories ended slavery. However, technological progress does not necessarily coincide with social progress. Sugar production during the time of American slavery also relied on advanced manufacturing technologies and chemical processes. The enslaved persons who worked in mills, refineries, or other manufacturies had to learn specialized engineering knowledge, even though they were not paid or recognized for their skills. Additionally, modern workers may continue to face discrimination or poor working conditions, regardless of whether they use modern machinery.

The Story Book of Sugar During the interwar period, author-illustrator team Maud and Miska Petersham created some of the most memorable fiction stories and textbooks for children. With publishers’ renewed interest in children’s books about everyday life, the production story genre was revived in the US with a series by Janet Smalley, closely followed by the Petersham’s comprehensive series comprised of five textbooks: The Story Book of The Things We Use (1933), about houses, food, and transportation; The Story Book of Earth’s Treasures (1935), about gold, coal, oil, iron, and steel; The Story Book of Wheels, Ships, Trains, Aircraft (1935); The Story Book of Foods from the Field (1936), about wheat, corn, rice, sugar; and The Story Book of Things We Wear (1939), about wool, cotton, silk, and rayon. Each of these five contain sections on different commodities that could be purchased as separate volumes. Most of the contents from The Storybook of Sugar (1936) also appear in the volume Foods from the Field (Bader, 93-97). This way of organizing a series by related commodities follows the same marketing strategy used by John Wallis, over a hundred years earlier. The title page for The Story Book of Sugar features a black child chewing cane. Another child chewing cane appears on the dust jacket for The Story Book of Foods from the Field. And a similar boy appears in the corner of an image depicting the cane harvest, titled “In the Sugar-Cane Field.” This cane harvester, chewing cut cane, has a long history. The figure appears in sugar production stories over the past two hundred years, changing to represent the labor force primarily responsible for sugar production, from enslaved Africans to free workers of different races and ethnicities. What is this figure’s perennial appeal? One possibility is that the harvester chewing cane encourages readers’ empathy without challenging their privilege: The image reassures privileged consumers who purchase and eat sugar far away from where cane is grown that children involved in the sugar labor force have plenty of food—indeed, they enjoy treats, just like children everywhere. While encouraging readers to sympathize with producers, such images also spread a cheerful veneer over questionable labor practices. In earlier production stories, the cane chewing figure originated with proslavery literature, which depicted slaves eating cane during harvest to contradict accounts of starvation in cane fields. However, the Petershams partially transform the image by making the cane chewer a child who meets the reader’s gaze. They also feature children eating grains in each segment of The Foods of the Field, where they eat bread, rice, and corn. This suggests that the Petershams are combining two visual tropes: the cane chewing harvester with the child consumer (who generally appears on the final spread of production stories, see for e.g. Hollos’s books). The Storybook of Sugar covers different sweeteners: honey, cane sugar, beet sugar, and maple syrup. Despite this global perspective on sweets, The Story Book of Sugar credits European ingenuity for sugar’s development by focalizing the story through white characters. For instance, the text acknowledges that mass cultivation of sugarcane began in India, yet readers learn about this fact from the perspective of Alexander’s soldier. The tall, armored man dominates the page, as a strong but relatively friendly figure, who “discovers” sugar during an invasion of regions that are now parts of Pakistan and India. Likewise, the section on Spanish sugar cane credits a “negro boy” sent to “the Brothers of the Jesuit Monastery in New Orleans” with figuring out how to cultivate cane, but the text glosses over the child’s enslavement by grouping him with the plants: “Again plants were sent to the Brothers in New Orleans. This time a Negro boy, who knew how to care for them, was sent with them.” The accompanying illustration positions the Spanish overseer in the foreground, his back to readers, which invites viewers to survey the sugar cane plantation from his perspective. The image includes enslaved persons, their bodies bent in labor, but signs of violence and coercion are downplayed. The modern refinery in the final spread captures another visual convention of production stories: the love of modern technology. Factory scenes usually make machinery the star, using repetition to create aesthetic appeal. Wondrous machines draw the viewer’s eye. We admire their size and strength, while human operators seem small and unimportant. In production stories, workers may appear as disembodied hands, or as nearly unrecognizable figures on a massive factory floor. (For a contrasting approach, see the recognizable faces in The Story of Your Coat.) In historical surveys of sugar production, machines capture the imagination after the abolition of slavery in the United States, and texts may even praise machines as “slaves,” as if modern factories ended slavery. However, technological progress does not necessarily coincide with social progress. Sugar production during the time of American slavery also relied on advanced manufacturing technologies and chemical processes. The enslaved persons who worked in mills, refineries, or other manufacturies had to learn specialized engineering knowledge, even though they were not paid or recognized for their skills. Additionally, modern workers may continue to face discrimination or poor working conditions, regardless of whether they use modern machinery. -

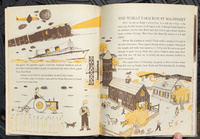

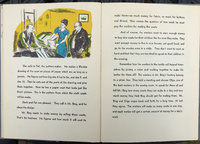

The Story of Your Bread Since the nineteenth-century, many production story series have included a volume on bread, a food that holds symbolic significance in Christian cultures that associate “daily bread” with both holy communion and basic sustenance. This second book on bread by Clara Hollos, published by Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor at Young world Books, follows a similar approach to the contemporary Petersham series of production story classroom textbooks. Hollos humanizes a genre that usually focuses on process over people. Alongside technological inventions, Hollos describes the social context of production, including slavery, serfdom, and hunger. Illustrations by Lászlo Roth change style to reflect that “people all through the centuries had their own ways of drawing and painting,” as well as their own ways of making bread, the “king of foods.” Unlike her first book on wool coats, The Story of Your Bread offers a global historical survey of bread making, from “the Stone Age to our times,” in which farming and baking are indexes of civilization. This pan-historical approach to production stories takes after some of the earliest production stories. The Arts of Life by John Aiken (1803), for example, argues that technology, cooperation, and government initially arose from the desire to provide for three basic human needs: food, clothing, and shelter. Such production stories recapitulate the story of mankind organized around single commodities (sometimes groups of commodities), creating a progressive history that culminates in the modern, technologically enhanced production of the goods enjoyed by the reader. In production stories, this panhistorical approach often naturalizes the economic dominance of Europeans and European Americans. Nowhere is this more clear than in the final spread of The Story of Your Bread. Four human figures represent different phases in history: “Stone age child,” Egyptian child,” “Roman child,” and “Greek child.” Underneath these, the text states, “And now it give strength to the modern child, who is—YOU,” with a picture of a boy flexing his muscles. Although different races and ethnicities appear in Lászlo’s illustrations, history culminates in the strength of this white male child, who represents the book’s reader and bread eater. Books for younger readers balance a celebration of modern technology with assurances that things will stay the same. In “The Wheat Farm Run by Machinery,” a family farm relies on tractors and modern chemistry, and the farm is flanked by the transportation network that connects agriculture to the city: planes, trains, steamships, and suspension bridges. The farmer’s sons, Butch and Ned, study chemistry at the university, expertise they apply to test the soil and understand what plants will grow. Yet the emphasis on a generational family unit promises readers that farm life will continue from one generation to the next. New modes of communication and transportation will, the image suggests, actually support cultural continuity for families like this one. Similarly, another image of farming families during the harvest features a nostalgic scene of dancing and feasting, juxtaposed with a roadroad map of the US. Again, the modern family of farmers is predominantly European American, suggesting a racially narrow vision of who uses and prospers from new technologies. The book is more inclusive where class is concerned. The image of the large factory where people bake bread, for instance, shows workers with distinct faces and appearances, which gives a sense of individuality. The accompanying text describes the many different kinds of bread that bakeries produce for sale at the store and gives words for bread in different languages. Bread is the “king of foods,” not because only kings eat bread, but because everyone eats bread. Bread can feed large populations and keep them strong: “Most of the world’s work gets done by people who eat bread. They eat a great deal of bread because it is the cheapest of foods and they cannot afford to buy lots of meat and eggs and cheese. The healthiest workers are the ones who eat bread made of whole grains along with other good foods. By eating bread people get the strength they need to do the world’s work.” The page concludes by celebrating farmers for their important work, because they grow “the wheat from which our bread is made.”