Chapter 9: Ethnicity, Immigration, Discrimination, and Social Dynamics

Several of our state’s Crossroads: Change in Rural America host organizations addressed yet another significant contributor to rural Illinois’s ongoing evolution: interactions among people of various ethnicities and places of origin. Many of those interactions have intersected with tensions related to economic mobility and access to resources. Often, they have been characterized by discrimination, discord, and even violence, but as some of the hosts’ companion exhibitions and programs indicated, peaceful coexistence and fellowship are achievable and worth pursuing.

Some rural Americans, however, have been slow to acknowledge the distinctive strengths or even the basic humanity of others who have resided alongside them. Discrimination is all too common a theme in the histories of many rural places, as the DeKalb County History Center’s companion exhibition (also available as an online exhibit) indicates.

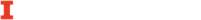

“When people hear about Native American history, many think only of history before permanent settlers [of European ancestry] arrived. Yet the story of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation is a current issue in DeKalb County, and more specifically, in Shabbona,” said the exhibition text. “The Department [Bureau] of Indian Affairs is conducting an Environmental Impact Study based on the Potawatomi Nation’s desire to build a 24-hour bingo hall in Shabbona. The decision to build a casino has led to a complicated legal battle.

“The Nation bought 128 acres in 2006, in addition to filing a lawsuit reclaiming 1,280 acres of land that was given to Chief Shabbona in the 1829 Treaty of Prairie du Chien. The land was sold at public auction when local settlers claimed the property was forfeited because no one had lived there for decades.

“Some residents believe the bingo hall will be good for the local economy. The Potawatomi Nation estimates that it will bring in 930,000 visitors and add $40 million to the local payroll. The group is willing to pay DeKalb County 2.5 percent of its revenue (a projected $800,000), plus $250,000 to the village of Shabbona.

“Those in opposition worry about the casino’s proximity to a state park, an increase in traffic, negative environmental impact, and higher crime.”[1]

Various other ethnic communities represented in DeKalb County were also discussed in the History Center’s companion exhibition and programs.

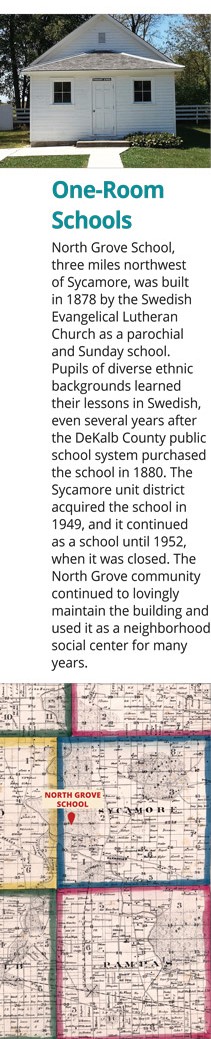

“North Grove School, three miles northwest of Sycamore, was built in 1878 by the Swedish Evangelical Lutheran Church as a parochial and Sunday school. Pupils of diverse ethnic backgrounds learned their lessons in Swedish, even several years after the DeKalb County public school system purchased the school in 1880,” the exhibition text noted.[2]

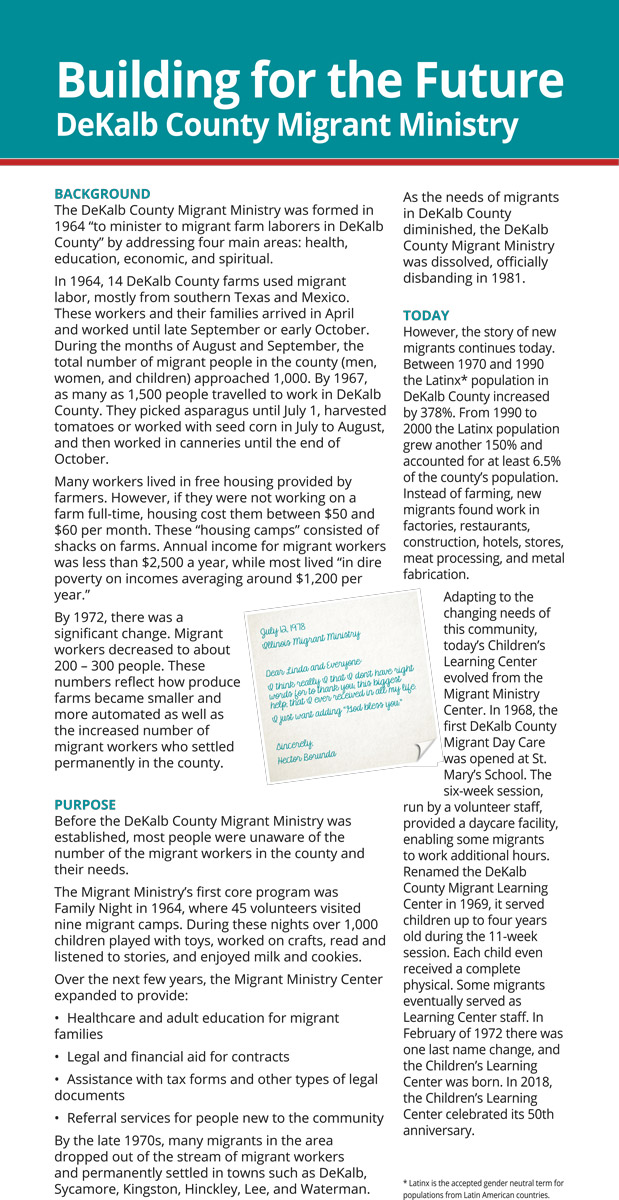

In the 1960s, the number of Latino and Latina migrant workers, mostly from southern Texas and Mexico, who arrived in DeKalb County each spring for employment began increasing significantly. The exhibition explained, “By 1967, as many as 1,500 people traveled to work in DeKalb County. They picked asparagus until July 1, harvested tomatoes or worked with seed corn in July and August, and then worked in canneries until the end of October.”

The text continued, “Many workers lived in free housing provided by farmers. However, if they were not working on a farm full-time, housing cost them between $50 and $60 per month. These ‘housing camps’ consisted of shacks on farms. Annual income for migrant workers was less than $2,500 a year, while most lived ‘in dire poverty on incomes averaging around $1,200 per year.’”

The DeKalb County Migrant Ministry, founded in 1964, sought to improve the quality of life for those workers and their families by providing medical services, educational opportunities, and various forms of legal and financial aid, as well as activities for children. A facility established by the ministry, now called the Children’s Learning Center, celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 2018.

Although automation reduced the demand for migrant labor on produce farms in the early 1970s, “Between 1970 and 1990 the Latino and Latina population in DeKalb County increased by 378 percent. From 1990 to 2000 the Latinx population grew another 150 percent and accounted for at least 6.5 percent of the county’s population. Instead of farming, new migrants found work in factories, restaurants, construction, hotels, stores, meat processing, and metal fabrication,” said the exhibition text.[3]

The History Center offered Spanish-language tours of Crossroads: Change in Rural America and its companion exhibition. The center also presented a program featuring the DeKalb County Latino 4-H Club.[4]

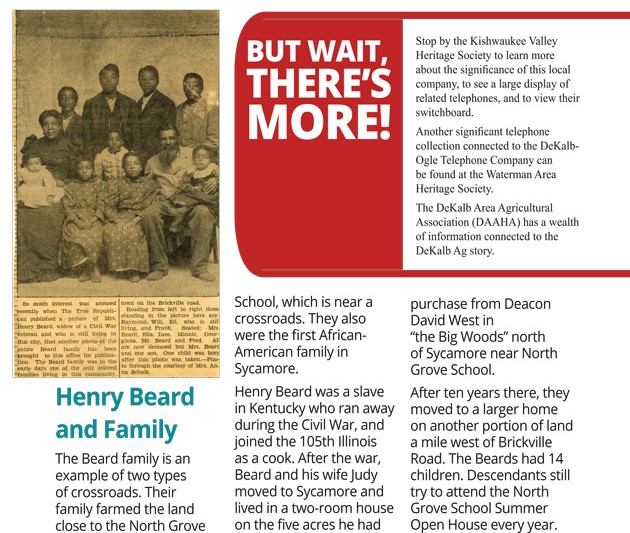

The center’s companion exhibition also acknowledged the first African American family in Sycamore: “Henry Beard was a slave in Kentucky who ran away during the Civil War and joined the 105th Illinois as a cook. After the war, Beard and his wife, Judy, moved to Sycamore and lived in a two-room house on the five acres he had purchased from Deacon David West in ‘the Big Woods’ north of Sycamore near North Grove School,” the school established by Swedish Americans, described above.

The exhibition continued, “After ten years there, they moved to a larger home on another portion of land a mile west of Brickville Road. The Beards had 14 children. Descendants still try to attend the North Grove School Summer Open House every year.”[5]

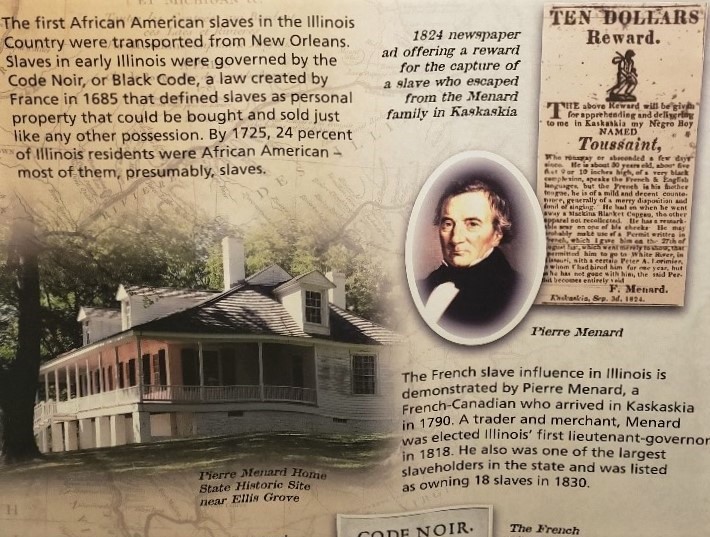

Not all African Americans who lived in Illinois during or prior to its first century of statehood arrived there of their own volition. As the sections of Chester Public Library’s companion exhibition devoted to Kaskaskia and Chartres noted, some of the French colonists who resided there in the eighteenth century enslaved Indigenous and Black people. Although the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and subsequent laws officially prohibited slavery in Illinois, some of those French colonists or their descendants, as well as white people who migrated from the Southeast, continued to practice slavery-in-all-but-name during the first several decades of the nineteenth century by coercing or misleading the people whom they had enslaved into becoming indentured servants with indentures of up to ninety-nine years.[6]

(The majority of settlers in the early statehood period came from slave states. Many of the most prominent public officials during Illinois’s formative years were natives of Virginia, the Carolinas, Kentucky, Tennessee, or other locations in the South, and some continued practicing slavery or something disconcertingly similar to it after arriving in this ostensibly free state. For a comprehensive account of slavery and conditions resembling slavery in our state during that period, see Bondage in Egypt: Slavery in Southern Illinois by Darrel Dexter, a friend of Illinois Humanities; the book was published in 2011 by the Southeast Missouri State University Center for Regional History.)

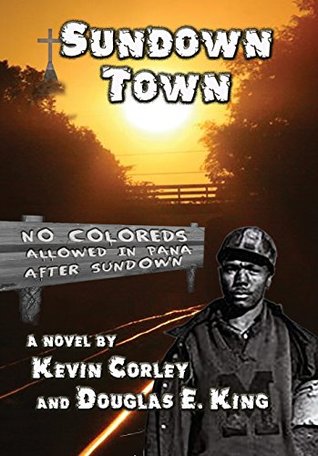

Slavery and indentured servitude were not the only means by which African Americans’ labor was exploited in nineteenth-century Illinois. Sundown Town, the novel by Kevin Corley and Douglas E. King that was featured in the Lake Shelbyville Visitors Center’s opening-day program, is based on historical events that occurred in Pana in nearby Christian County and led to violence, culminating in the Pana Riot of 1899. Corley and King drew upon primary sources in the archives of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum and the University of Illinois Springfield.[7]

The United Mine Workers, then a relatively young organization, declared a strike affecting many coal mines in Illinois in 1898. After unsuccessful attempts to hire local white residents and Chinese immigrants to break the strike, owners of a mine near Pana traveled to Birmingham, Alabama, to recruit African Americans, some of whom had mining experience, to work in that capacity. The mine owners announced that they were offering employment opportunities, but they opted not to disclose that the reason why those opportunities were available was that the miners who had held those jobs were on strike.[8] Corley and King fictionalize the scenario this way:

“I’m Mr. Howard Smithson,” the man said, emphasizing the mister. “I had these signs posted. The war in Cuba has drained our work force, and we need coal miners.”

“You paying our colliers a decent wage for a decent day’s work?” Big Henry asked without softening his deep, baritone voice.

“That’s right,” Smithson said. “In a little town called Pana, Illinois.”

Garfield had just deciphered the name of the town as Pan-a, but this man pronounced it Pain-a.

“How those white folks up yonder goin’ to treat us?” Big Henry asked.

Smithson pointed to the chain gang down the street. An elderly white woman had just hooked her umbrella around old Beau’s ankle chain, tripping him. The guard flogged him while the white citizenry laughed and threw rocks at the old Negro.

“You’ll be treated a lot better than you’re being treated in this godforsaken country,” Smithson said. “Be at the rail station Monday morning at nine o’clock. Wives and children are welcome and may be employed as rock pickers–as long as their men are in good standing.”

—Kevin Corley and Douglas E. King, Sundown Town (self-published, 2018), pp. 4-5.[9]

Unfortunately, Smithson’s assurance that the African American miners would receive better treatment in Illinois than they had in Alabama proved false. It soon became apparent that the mine owners had hired them to be strikebreakers. Many of the local miners, who were predominantly white, as well as many other supporters of the union within the community, bitterly resented the newcomers for interfering in the strike. In many cases, their resentment was exacerbated by their preexisting racial prejudices. The African Americans’ unawareness of the pretext on which they had been hired did not persuade their local adversaries to absolve them (if they even knew of it). Both the white miners who were on strike and the Black miners who unintentionally broke the strike felt animosity toward the mine owners for recruiting the latter under false pretenses. Some of the Black miners left, but others remained and defended their right to make a living. At least one law enforcement officer empathized with the African Americans and tried to protect them, but others who were either pro-union or racist (or both) harassed them and charged them with petty crimes.

All of these mutual hostilities created a volatile social atmosphere that sometimes erupted into violence, prompting Governor John Tanner to dispatch National Guard troops to Pana to maintain order. On April 10, 1899, a riot occurred. Five Black people and two white people died, and six African Americans were wounded.[10] Corley and King present their fictionalized account of the circumstances that triggered the riot as follows:

Henry Stevens had finally had enough. Over two dozen Negroes were in the city lockup for everything from burglary to making advances toward white women. Many had accepted the United Mine Workers’ offer to return to Alabama and had not been heard from since. April tenth was a wet, dreary day. Big Henry was in a melancholy mood. He decided to go talk to his jailed friends and find out if they were alright. Knowing the deputies would refuse him visitation, he circled around to the back alley and looked in through the cell window.

—Corley and King, Sundown Town (self-published, 2018), pp. 289-290.

As the conversation proceeded, one of the incarcerated miners asked his visitor,

“You fixin’ to get violent, Big Henry?”

“Seems to be the times require it,” Big Henry echoed the words he had heard from Jeb Turner. “But I’m sorrier for that than you’ll ever know.”

“Then get us outta this here lockup, and let’s get it did.”

“Get away from that window!” a voice yelled from the entrance to the alley. “Them are jail birds, and they got nothing to say to the likes of you.”

Bucktooth and Quits jumped away from the window just as a streak of lightening flashed across the heavens. The wind began to pick up, and the sky transformed into dark, swirling thunderhead clouds.

“These miners don’t want to go back to ‘Bama.” Big Henry turned toward the deputy. “If they go missin’, I’ll be comin’ for you, Cyrus Cheney.”

“By G**, you ain’t threatenin’ me…” Cheney shouted.

A flash of lightening reflected off the silver revolver. Big Henry dove behind an empty beer barrel. The first bullet the deputy fired split through the wood. Something stung like a bumblebee against Henry’s neck.

Two more deputies ran up and started firing at him. He pulled his own revolver tucked under his belt. Raising it, he fired two quick shots over the barrel toward the men, and then ducked low as he ran to the end of the alley and turned quickly behind the protection of the building.

A dozen men and women stomped through the muddy street to the nearest doorways. He was about three blocks from the safety of the Eubanks Company Store, but he needed to cross the street. Blood ran down beneath Big Henry’s shirt, so he decided he’d better get to the other side while he still had the chance. At full sprint, he crossed the road and dove behind a horse trough just as he heard more gunshots and the buzz of bullets passing near him.

—Corley and King, Sundown Town (self-published, 2018), pp. 292-294.[11]

The Pana Riot of 1899 was not an isolated incident. Similar conflicts occurred around the same time in several Illinois communities where coal mines had recruited African Americans to work, unbeknownst to them, as strikebreakers, notably including Virden in Macoupin County, where thirteen people were killed and thirty-five wounded in an outbreak of violence on October 12, 1898. In the aftermath of those occurrences, a number of communities, including Pana, became sundown towns: places where, by either law or custom, African Americans were not allowed at night (and therefore could not be permanent residents if the ordinance or custom was strictly enforced).[12] Sundown towns represented a form of racial segregation that was distinct from both the Jim Crow laws of the rural South and the redlining, blockbusting, and similar practices that occurred in Northern cities.[13]

Pana now has ordinances requiring equal opportunity and prohibiting discrimination in housing,[14] and protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement took place in several former sundown towns in central and southern Illinois during the summer of 2020.[15] To what extent do such developments indicate that dominant cultural attitudes regarding race have changed or are changing in those communities? Does more progress remain to be made, and, if so, how should that progress be pursued and assessed? Those questions seem worth pondering.

- “The Land,” section of a companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, DeKalb County History Center, Sycamore, IL, May 11-June 22, 2019, content from which is available at https://dchcexhibits.org/crossroads/land/. ↵

- “Building for the Future,” section of a companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, DeKalb County History Center, Sycamore, IL, May 11-June 22, 2019, content from which is available at https://dchcexhibits.org/crossroads/building-for-the-future/. ↵

- “Building for the Future,” section of a companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, DeKalb County History Center. ↵

- Michelle Donahoe, telephone interview with author, September 27, 2019. ↵

- “Building for the Future,” section of a companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, DeKalb County History Center, Sycamore, IL, May 11-June 22, 2019, content from which is available at https://dchcexhibits.org/crossroads/building-for-the-future/. ↵

- Companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, Chester Public Library, Chester, IL, September 8-October 20, 2018; Darrel Dexter, Bondage in Egypt: Slavery in Southern Illinois (Cape Girardeau, MO: Southeast Missouri State University Center for Regional History, 2011); Logan Jaffe, “Slavery Existed in Illinois, but Schools Don’t Always Teach That History,” ProPublica, June 19, 2020, https://www.propublica.org/article/slavery-existed-in-illinois-but-schools-dont-always-teach-that-history; David MacDonald and Raine Waters, Kaskaskia: The Lost Capital of Illinois (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2019); Tom Willcockson, French Colonial Fort de Chartres: A Journey in Time (Prairie du Rocher, IL: Les Amis du Fort de Chartres, 2018), 12-15. ↵

- Sundown Town website, https://sundowntown.org, no longer available as of October 2021. ↵

- John H. Keiser, “Black Strikebreakers and Racism in Illinois, 1865-1900,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society vol. 65, no. 3 (1972): 320-326; Noah Lenstra, “The African-American Mining Experience in Illinois from 1800 to 1920,” Student Publications and Research – Information Sciences, Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship, 2009, http://hdl.handle.net/2142/9578, 20-25. ↵

- Kevin Corley and Douglas E. King, Sundown Town (Self-published: 2018), 4-5. Quotations from Sundown Town appear by generous permission of the authors–Kevin Corley, e-mail correspondence with author, November 30, 2021. ↵

- Keiser, “Black Strikebreakers,” 320-326; Lenstra, “The African-American Mining Experience,” 20-25. ↵

- Corley and King, Sundown Town, 292-294. ↵

- Keiser, “Black Strikebreakers,” 320-326; Lenstra, “The African-American Mining Experience,” 20-25; James Loewen, Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism (New York: The New Press, 2005), 159-161. ↵

- Loewen, Sundown Towns, 3-14. ↵

- City of Pana, Illinois, Section 2-105, “Equal Employment Policy,” and Section 11-53, “Prohibited Acts,” Code of Ordinances, date accessed or published, https://library.municode.com/il/pana/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=COORPAIL. ↵

- Kaitlin Cordes, “Hundreds Rally in Effingham for Social Justice, Saying Black Lives Matter,” Effingham Daily News (Effingham, IL), June 6, 2020, https://www.effinghamdailynews.com/news/local_news/hundreds-rally-in-effingham-for-social-justice-saying-black-lives-matter/article_4dc276c6-a837-11ea-a57d-d7f72223f502.html; Marilyn Halstead, “Nearly 100 Gather in Pinckneyville for Black Lives Matter Rally,” The Southern Illinoisan (Carbondale, IL), June 11, 2020, https://thesouthern.com/news/local/nearly-100-gather-in-pinckneyville-for-black-lives-matter-rally/article_122e80a3-75e8-53f2-be0d-962385b5a52d.html; Logan Jaffe, “A Sundown Town Sees Its First Black Lives Matter Protest,” ProPublica, June 12, 2020, https://www.propublica.org/article/a-sundown-town-sees-its-first-black-lives-matter-protest; Matt Meacham, “Reflections on Dialogue, Memory, and Race in Downstate Illinois,” Illinois Humanities, July 2, 2020, https://www.ilhumanities.org/news/2020/07/toward-a-more-just-future-for-illinois-communities-reflections-on-the-role-of-the-public-humanities/; Molly Parker, “In Wake of Floyd Death, Rural, White Southern Illinois Towns are Reckoning with Racist Past,” The Southern Illinoisan (Carbondale, IL), June 6, 2020, https://thesouthern.com/news/local/in-wake-of-floyd-death-rural-white-southern-illinois-towns-are-reckoning-with-racist-past/article_dce170eb-962b-534f-955c-e1e38e50ac94.html; Steven Spearie, “Small Central Illinois Communities Stepping Up with Protests, Actions,” The State Journal-Register (Springfield, IL), June 8, 2020, https://www.sj-r.com/story/news/politics/county/2020/06/08/small-central-illinois-communities-stepping-up-with-protests-actions/114282580/. ↵