I cannot pass over the basics about the man himself.

Middling height, well-knit, steady and robust, with a smiling forthright gaze and a firmly sonorous voice—isn’t that enough to suggest “a healthy mind in a healthy body,” a man of good will, with all the energies in harmony to make a human being what he is supposed to become? For stealing the divine fire and concealing it in a hollow rod, the Titan Prometheus suffered on his rock; as a mere mortal, Monet sought the conquest of heavenly light, to give us the wonder of the life around us, to celebrate its changefulness, to open its nuances for us to comprehend.

Demigods, legends, tales of wonders: to tell of one actual human being doing human work, hyperbole and distortion do no good. We need the truth and nothing less than that. Look at the shape of the head, powerful like a fortress by Vauban[1] when he was on the attack, protecting his center while blasting away at a worldly experience that resists us all with secrets and mysteries. The sky, the fields, valleys, mountains, waters, forests—all around, the natural world, scattering, shape-shifting, lies open to us, only to break away again whenever we try to catch it. One astounding moment after another, on our journey to insights which, even in a work of artistic genius, we can never do more than come near.

When I tell you that Claude Monet was born on rue Laffitte in Paris, in the neighborhood where the picture galleries are now—a fact that one might twist into an omen of sorts—I tell you next to nothing. But when I add that he grew up in Le Havre, and that he was intoxicated by the heady brew of light along those shores, spilling down on restless seas from infinite skies, I might come closer to explaining how he came to know the mad exuberance of the air, every shade and shadow and hue in the reckless abandon of wave and wind. From childhood, Monet was enthralled by the vast horizons of that coast. To make a little money in his youth he turned out prosaic sketches, caricatures of people he knew. “I love to draw,” he wrote, though he wasn’t born for that; and when he reached the age of fifteen, his work with a pencil had brought in enough to pay for a trip to Paris.

Closer to home, in the resort town of Sainte-Adresse, he had come to know Boudin,[2] who took him out to paint in the open air, where Monet encountered the palette of nature itself. A flame leaped in his heart; he found his reason for being alive, and he began his quest for the skills to match his dreams. Troyon,[3] whom he had also met, offered him some peculiar advice, to go and train in the atelier of Couture[4]—but staying clear of academe, Monet soon became friends with Camille Pissarro in Paris; and he later reproached himself for spending too much of his time there hanging around in the Brasserie des Martyrs. It was there, however, that he met Albert Glatigny, and the unforgettable Théodore Pelloquet, who fought a duel with swords over Manet’s Olympia;[5] and there was Manet himself, and many others as well: Alphonse Duchêne, Castagnary,[6] Delveaux, Daudet, Courbet—and lasting friendships took shape.

In 1860 a conscription lottery put him into an army regiment, the Chasseurs d’Afrique, for two years of service which, he said later, did him a lot of good. With his skills as an artist he turned out a portrait of his captain and was rewarded with a leave of absence. When he fell ill, he was granted another leave for convalescence, after which his father, convinced now of the depths of his son’s dedication to his calling, resolved to pay for a substitute in the service. And so it was that Claude Monet headed for study in the atelier of Gleyre; but he also resolved to follow Jongkind and Boudin on their forays into the countryside to see the world as it truly is. In 1864, Renoir, Bazille, and Sisley all joined the cause. “In the Salons of 1865 and 1866 my first experiments were favorably received,” wrote Monet. And then came Courbet, to see Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, that great plein air canvas by this young man “who actually paints something besides angels.” They stayed friends—and later in life Monet affirmed that Courbet “had lent me money when times were hard.”

The Africa days were now behind him; as an artist, he said that although the countryside there was spectacular, he could not emulate Delacroix and catch its colors on a palette. Already, however, Monet was feeling something deep within, like a supernatural monster that would take dominion over his flesh, his blood, his life. For him it seemed that the die was cast, that he would always be in pursuit of shafts and dances of light itself, never tiring in his quest for its great secret.

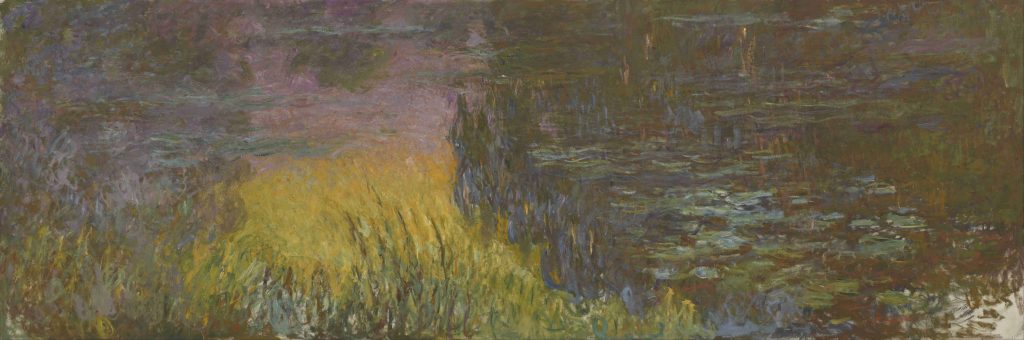

In the Nymphéas panels, we find him lost in his struggle to realize something impossible. From his restless hand, skyrockets of transparent brilliance streak across the canvas, an impasto that seems to burst into flame. Genius in the daring brushwork, genius also in the alchemies of color on his palette, from which Monet could gather, in a single confident sweep, drops of a luminescent daybreak dew, lasting tribute to a morning where nothing like this can abide. Close up, the canvas looks like a riot of mismatched colors; from a few feet away, at the right viewpoint, they come together, connecting, blending, a delicate construction of natural forms, catching the precision and the poise in the play of sunlight. This is a miracle I will need to come back to, later on.

One day I told Monet: “This is humiliating for me. You and I never see things the same way. When I open my eyes I see shapes and nuances of color that I take for granted as the way the world is, until somebody shows me that I’m wrong. My eye can go no deeper than the reflecting surface. With you it’s all different. The sharp blade of your gaze slices through these outer crusts of appearance; reaching the inner truth you break it down into fundamental colors, and then with your brush you recreate it with subtlety, with all its intensity, as an experience for us all. And when I’m looking at a tree and seeing nothing but a tree, you, with your eyes half-closed, are saying to yourself ‘How many shades of how many colors can we experience in these gradations of light merely upon this trunk?’ With that, you set to work disrupting all of our conventional ways of seeing, to build for us a fresh understanding of the harmony of the whole. And at times you’re vexed, in this struggle to see into the life of things, to come as close as you can to the best possible interpretive synthesis. You’re troubled with self-doubts, not seeing that you have set out on a journey towards the infinite, and that you’ll have to settle for coming close, but never quite getting there.”

Monet answered me: “You cannot imagine how right you are about that. This is what haunts me, bringing me joy and tormenting me every day. This is how far it can go: one day, finding myself by the open coffin of a woman who was, and still remains, very dear to me, and with my eyes fixed on her tragic visage, I caught myself looking for a sequence there, degradations of tone and color that death was bringing into her motionless face. Shades of blue, yellow, gray—what was I thinking?! That’s how bad it was. The desire was natural enough, to do a final portrait of someone who was leaving us forever; but even before I had that thought, to represent those features that meant so much to me, my immediate and intuitive response was to the shock of the color, letting it pull me into a mindless repetition of what I do every day, like a farm animal tethered to a mill. And that, my friend, is pathetic.”

Monet’s eye—it was nothing less than the entire man. Endowed with exquisite retinal sensitivity, he focused all of his attention on the supreme harmony of the natural world as a portal into the comprehension of universal truth. All masters of painting have this gift; what strikes us about Monet is that his entire life was dedicated to it. Devoted to his family and to his friends—a circle he took joy in expanding, to shower it with his generous friendship—he received, from his loving sons and also from his daughter-in-law Madame Blanche Monet (a painter in her own right when time allows), all the attention he could want in a life so structured and intense. Whenever he put down his brush, he ran to his flower gardens, or settled into his easy-chair to think about his pictures.

With his eyes closed and his arms hanging motionless and limp, he sought for moments of sunlight that had got away; and when he failed (or perhaps only imagined it), he lapsed into sour thoughts about the work. But any quick pleasantry could fetch him back to contentment, at least to a measure of hope, though he would often grumble about the trials of the coming day. And so it went: everything in the man given over to this desire, this endless anticipation of sunlight’s caress. Carried by his dreams so far beyond his own human capacity to respond, his eye was like some triumphal arch, open to every stirring from beyond, to the exaltation of being alive.

I don’t see that Monet ever thought seriously about explaining his own work. Nothing to him could have seemed like a bigger waste of time. Born with a palette in his hand, he couldn’t imagine life anywhere else than in front of a canvas, to catch and hold those moments of vivacious light with which the world arranges itself, as if gazing in a mirror, into illusions of stillness. To feel, to think, to yearn as an artist: in the realms of painting there was nothing to hold him back. Like an archer with a straight arrow and his bow at the ready, he waited only for the right moment to let fly. He watched for it, like anyone driven to express his own perceptions as completely as he possibly can, and knowing that no such quest can ever truly succeed.

As I’ve already said, nothing seems more beautiful to me than this concentration of every human capacity on one exquisite purpose, an ideal whose pursuit brings the whole self into harmony. Obviously this is genius, yet also a mystery, this absolute convergence of everything we are and do for a perfect flowering of grandeur and beauty. Though we collectively venerate the names of artists who dazzle us in pursuit of this dream, we are less sure in our regard for nuance, chance effects, enigmas whose meanings can never come clear.

There is no shortage of painters out there, and many of them have won high honors that they rightly deserve. But among them Monet stands out in this way: once he achieved his own unique style he continued to develop it, beyond the series Les Meules and Les Peupliers,[7] the Rouen Cathedral facades, the Thames at London, all the way to the masterwork of the Nymphéas. To talk about such an adventure is to take a risk: interpretation can collapse into a kind of giddy hyper-sensitivity that shuts other people out rather than shows them something new. Monet himself was trying to say something like that when he said, as he often did, “Sooner or later they’ll understand—but I did come along too early.” Whenever he said this, his steely-black eyes, bedded in their sockets like field-mortars, were engaged with the play of light upon everything in the world, to open spectacular insights, a unified sense of all that is and all that seems to be.

In everything he did as an artist, this was the dedication of Claude Monet.

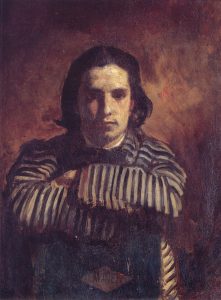

Looking back at these early years of his career, how shall we imagine him in this struggle for the conquest of light itself? He was largely unknown, for Durand-Ruel, with his expert eye and his skills as a promoter, had not discovered him yet. What did he look like, this young contender, gripped with an ambition that so often leads nowhere? We have little to go on, except for a portrait of him at the age of eighteen by Déodat de Séverac.[8] The face is full of dramatic energy; the forehead, which would stand out so strongly in the rare self-portraits from later years, is already dominant here. Séverac himself was beginning to think like a true painter, deconstructing his subject to recreate it as visual experience, with emphasis on strong and clear transitions. What dominates here is the audacity of the gaze, coming straight at us fearlessly, and also in a sense without hope, sustained by an idea with no concessions to circumstance or fate. All in all, the portrait gives us a sense of power in a moment of taking dominion. Indeed, that was about to happen.

A study from 1875, Renoir’s Claude Monet at Work[9] is every bit as important. Here the body of the young man is left vague; the face seems softer, gentler. Nonetheless, the demeanor of this young artist conveys a feeling of conviction joined with manly energy. The mouth is tight no longer; freely, the nostrils draw in the air. And ablaze with curiosity, the eyes focus inexorably upon the play of light in the room, the abiding mystery. The battle is joined, and these are the first waves of an assault that will never let up.

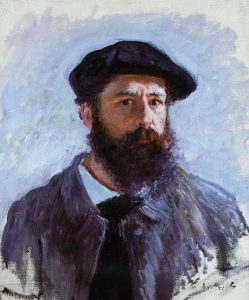

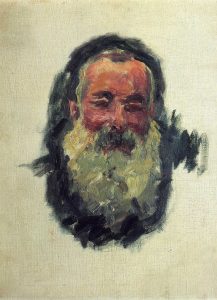

At the Giverny house, in a self-portrait of Monet at the age of forty, we see the mature artist, full of vitality and stunning simplicity. Nothing could be less conventional, less contrived, less “stylized,” than this image of a man doing his work, entirely caught up in the expression of sensory experience and personal feeling. Seeking nothing less than to understand the natural world through the motions of its tides of light, he cannot let go of his resolve to get everything out of the experience, wherever he chanced to be or positioned himself, seeing it always as the core of the vast drama. Tranquil and self-assured like a skilled clairvoyant, he looks away with a gaze of candor and resolve. A world beyond seems to enrapture him, filling him with holy fire, a world whose inundations of light he must penetrate and subdue. Across his forehead the furrows tell of unwavering élan. Making no gesture at all, the artist is entirely composed, ready to spring into action: he sees, he understands, he decides, he is on his way. Such is our Claude Monet, guileless and balanced as we have not seen him before, all set to pour himself into his art. Trusting in his palette and gathered for a mastering leap when the moment of decision is there, he is present in all of his famous intensity, the innocent ardor of a visionary, to achieve his conquest of light itself, light leading him inexorably onward, light he has resolved to master.

At this point in his life the formative years are over, the talents and strengths brought into harmony for this overriding intent. Though his full triumph still lies ahead of him, with sure eyes he has already surveyed where he must go, the great field where the battle must be won. Only at the very end did Augustus recognize that the commedia of his own life had found its form and now was over; Monet, with no comedy in him, and troubled by the kind of self-doubt that can come like a luxury to those who have fulfilled their destiny, could see the handsome shape of his own drama, even as he balked at giving his Nymphéas to the people of France before his death. A final, endearing uncertainty: an honest and gallant completion for this life of selfless exertion.

In the year 1917, before the Nymphéas were completed, Monet painted three additional self-portraits which he spoke of only hesitantly, perhaps because he saw in them the limits of what he could do at that point in his life and did not believe he could surpass them in the days he had left. Two of these canvases show him in full daylight beneath one of his big straw hats. When he showed them to me he seemed to enjoy disparaging them: “I can do better than that,” he cried with scorn, “but I won’t have the time.” When he said that, I could see only too well what would happen next: for years, Monet had been in the habit of destroying canvases that displeased him by slashing them with a paint-scraper and kicking them to pieces.[10] Still in his studio, on studies for panels, we can see the mayhem inflicted in these outbursts of frustration and rage, showing no mercy to himself or his efforts.

Of the final self-portrait, the one that is now in the Louvre, I cannot write without feeling. It catches him at his best, his spirit aglow, with the final triumph in sight, before he was crushed by the unspeakable prospect of going blind. For anyone who knew first-hand the depths to which Monet could plunge when faced by the prospect of ultimate failure, and his ecstasies when he sensed that some great difficulty had been surpassed, there can be no doubt about his response. This final portrait shows his inner life at the moment when Monet began the soaring flight that culminated in the Nymphéas; and complete as they seemed, those two portraits he destroyed must be thought of only as preparation for the marvelous one that survived. Before the battle is joined, victory seems sure; for this warrior, the fanfare sounds before the fight begins.

But the powerful brow we see here once more, unscathed by anything the Philistines of his time could launch at him, also conveys the tragedy at the core of this glorious career. The price he paid is suggested in those wide, high temples of the skull, the center and seat of his poise and self-possession. Eyes half-closed as if to savor a dream, nostrils aquiver, the throat convulsed by energies deep within: the maestro we see here has reached, at this very moment, a thrilling apprehension of ultimate success. His excitement radiates even in this flowing beard, luminous and glorious, like a vexillum of Charlemagne, emperor of a new land.

Like others, I’ve understood that from the physical positions that Monet had to work from, an ordinary observer can see the canvas only as a riot of colors crazily applied. Take a few steps back, however, and natural forms and harmonies come miraculously clear, resolving what had seemed a chaos of dabs and brushstrokes; an astounding symphony of hues emerges from these thickets of intermingled color. Unable to move about like this when he was painting, how could Monet keep clear, in his own imagination, laboring so close to his canvas, all this intricate deconstruction and recomposing to make possible the overall effect? The sensitivity required for this had to be exquisitely delicate, all those responses, so quick and agile, to instants of perception, this headlong sequence of images striking the retina. What a gift, to bear up so well in this long and physical combat with light itself.

It goes without saying that Monet himself never indulged in theorizing about any of this. Nature had given him eyes fit for the challenge, and he trusted them, allowing no doctrines to get in the way—the most basic rule for doing a good day’s work. Settling down in silence before his subject, he began his interrogation, his face twitching as his eyes flashed back and forth: the subject, the palette, the leap of brush to canvas. As this drama unfolded there was no idle conversation. Once in a while, a question to his daughter-in-law Blanche Hochedé, who was always nearby; but often these queries really seemed more to himself than to anyone else. Like an aircraft taking off, he required a concerted effort to get himself effectively aloft. Then the hand with the brush would suddenly and freely lash out, like an épée thrust at the very start of a duel.

This self-portrait in the Louvre strikes me as Monet’s last testament to us all. In moments when he knew that he would make it, when he recognized, in his own best efforts, the realization of his highest hopes, he could be overwhelmed with a feeling of triumphal joy. This final, wonderful portrait catches that exultation. Its historical interest lies in how it shows us Monet in a whirl of excitement, the artist happy in the achievement of his dreams. After a life of labor, triumph radiates upon the face, the banishment of old and abiding fears by the certainty of ultimate success. In the brushwork here, we are shown, by a twist of fate, this culminating flash of exultation.

The Nymphéas idea had enthralled Monet for a long time. In quiet, every morning, along the shores of his pond, he spent hours watching the clouds and the blue skies moving in magical parades above his Jardin d’Eau et de Feu. With furious intensity he studied shape and encounter, variances in luminosity and penetration. Having mastered the art of assimilating so much into himself in the service of his interpretive strategy, what he sought now was to catch the moment in touches and details barely perceptible, in nature’s reflections of light on its infinite journey. From this magnificent effort, chronicled in one vibrant study after another, the Nymphéas of the Tuileries gradually took form. Only in 1916, after such extensive contemplation of his water-garden, a thousand different varieties of aesthetic challenge and critique, did Monet resolve firmly to do this work, and to have the vast new studio built that such an adventure required. When that order was given, the commitment was absolute and complete, requiring this aging painter not only to live up to his own exacting standards, but to see everything to the very end.

Numerous paintings of water lilies preceded the spectacular culmination that we now have in the Tuileries, and when we look back over that sequence, those final panels show levels of imagination and skill far superior to those early experiments that took shape in the grand new atelier. Though some of these were very beautiful, many were destroyed in those passionate and turbulent early days. Inevitably, it happened that some sought-for effect would come up short; and because our friendship allowed it, I would risk voicing my own opinion now and then. When I did so, I’d sometimes hear a growl in response, which meant “Well, we’ll see.” Sometimes I’d hear nothing at all. But from one visit to the next, I observed that from all this stubborn labor with brushes and oils, what was taking shape was marvelously replete with air.

My inchoate response to all this often centered on the clouds in these panels, which often struck me as unduly heavy—but I didn’t dare say anything about that. But one day I was in for a shock: cloudscapes that now seemed like irruptions of the lightest vapor. Again I held my peace; and as I looked closer I saw wisps of vapor on the wind, air alive with unraveling and caprice. Monet engaged with the world so raptly that he didn’t suffer comments from others lightly; but ceaselessly, he reconsidered, corrected, fine-tuning until in his own mind everything rang true. A perfectionist, he would never leave a cloud looking even vaguely like those animal-shapes that Hamlet points out to bedevil Polonius. No one was as careful as Monet.

Never one to give in to a first impulse, Monet revisited his own moments of inspiration again and again, always finding reason to fault himself for some shortcoming or other. There were times when he would vilify himself with reckless abandon, swearing that his life was one big failure and that there was nothing left to do except destroy everything he had done before vanishing himself. Some of his best works fell victim to these outbreaks of self-hatred; but many which are now held in high regard were luckily rescued from these rages thanks to the efforts of Madame Monet. I have already observed that two lovely self-portraits in full sunlight were obliterated on a single occasion; the one in the Louvre was saved by chance. One day, when Monet was saying nasty things about it, he went looking for the canvas just as I was getting ready to depart—and throwing it into my car, he said gruffly “Here! Take it away and don’t mention it again!”

Maybe he was looking for a way to shield himself from some new wave of stupid dismissal. When I told him that on the opening day for Nymphéas we should go arm in arm to see this work in the Louvre as well, he said “If we have to wait that long, then it’s good-bye to it forever.”

That sweet excursion never came about, I’m sorry to say, because Monet refused to release his water-lily panels before he died. So we have these two self-portraits—to mark the beginning and the end of his greatest era: from the wheat-stack series to Nymphéas.

Soon after, the cataracts showed up in both of his eyes, a disaster that beggars description. Thanks to surgery and expert medical care, the catastrophe of complete blindness was averted, at least for the time being. Though I was pushing for a more radical treatment, Monet would not take the chance that everything could go dark. So he settled for having his eyesight half-restored, allowing him to bring Nymphéas to completion.

This was nothing less than a miracle, for all that interplay of light, perceived now with eyes so profoundly changed, was very different from what it had been when the project was first taken on. For myself, I had one abiding fear, that entire panels could be totally lost. But for reasons I cannot explain, the project reached its happy ending, unscathed by this change from one mode of seeing to another. This time at least, blind luck was on our side; and I couldn’t help feeling that Providence had intervened on Monet’s behalf.

Still, he had to perform a miracle of his own, and everyone around him begged him to consider the work done, as there were good reasons to fear that one bad slip of the brush could wreak havoc. He let us talk, shook his head, gave no answer.

Time passed, and one day, leading me by the hand, he set me before one of the great panels: upon the surface of a pool of still water, a spectacular universe of light, broken here and there by reflections in shades of blue, adrift in variegated expanses of rose.

“Well, what about that?” he said playfully. “Though you never dared to critique, I knew well enough that the waters looked solid, like something cut out with a blade. All of that light had to be done over again. I didn’t want to risk that. But I decided to—and this will be my farewell. You were afraid I’d spoil it all. So was I. But despite my troubles, my confidence somehow returned, and despite these scrims over my eyes I could see well enough what I had to do, to keep faith with the idea that had guided me this far…. Anyway, look at it! Better? Worse?”

“I was wrong. As a painter, you are so perfect that even with your eyes in bad shape, you’re guided by all that they showed you when they were right, these exquisite harmonies of color.”

“That was luck.”

“A kind of luck that poor Turner never had.”

“Well, I am all done now. I am blind; I have no reason to go on. Even so, you know very well that I won’t let these pictures leave here as long as I’m alive. I’ve reached the point where my own self-criticism cuts deeper than anything the experts have to say. I’ve probably tried to accomplish here more than I can manage, and I’m willing to die without hearing whatever verdict fate wants to hand down. I have given these pictures to France. She can judge them however she will.”

- As a Marshal under Louis XIV, Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban oversaw the construction and refurbishing of hundreds of fortresses all over France and outlying dominions. ↵

- Remembered now for his seascapes, Eugène Boudin, nearing the age of fifty, participated in the first Impressionist exhibition in 1873, though he remained conservative in his style. ↵

- Thirty years older than Monet, Constant Troyon (1810–1865), much influenced by Dutch landscape painters of the seventeenth century, was associated with the Barbizon school. ↵

- Though he eventually rebelled against the Académie des Beaux Arts, where he had been trained, and opened his own atelier in Senlis, Thomas Couture is often classified now as “academic” in the tradition of Gros, Ingres, and Gérôme. ↵

- [Clemenceau’s note] He received a wound in the hollow of his left hand, requiring him to do a lot of explaining. It was Pelloquet who inspired Emile Augier to create the character of Giboyer. ↵

- A liberal politician and prolific journalist as well as an art critic, Jules-Antoine Castagnary, a close friend of Courbet, was one of the early champions of Impressionism. ↵

- Variously known in English as “The Wheat Stacks,” “The Haystacks,” or “The Grain-stacks,” the series Les Meules is more often showcased at special exhibitions than Les Peupliers, Monet’s paintings of poplar trees along a shoreline at different hours and seasons. ↵

- Clemenceau’s memory goes astray here: Déodat de Séverac, a composer of tone poems and operas who achieved considerable renown in Clemenceau’s middle years, was the son of Gilbert de Séverac, the painter who did the portrait of the young Monet. ↵

- Now commonly cited as Portrait of Claude Monet, in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. ↵

- Because these two straw-hat portraits from 1917 have not turned up, they may indeed have been destroyed by Monet. ↵