For a good dialogue, for an invigorating contagion of tastes, the arts do require a public, random collisions with “judges,” unevenly qualified as they might be to issue provisional rulings on this and that, matters that would require more schooling before final decisions are handed down. Such is the ungainly empirical process by which human knowledge first took shape; with the rise of experimentation and scientific method, telling truth from fantasy has become the domain of careful observation and the verification of fact. Even for feelings aroused in the presence of nature, or by art that seeks to represent it, the situation isn’t so different: the problem lies not with the feeling itself, but with explaining it to a public exercising its rights to speak out and nay-say at will.

With regard to cultural and emotional growth, every person reaches a limit proportionate to his intelligence. Revelations, myths and legends, teachings with or without a solid footing: all of these things turn up in our disputations. Somebody says “Yes”; “No” says someone else—and those of us who keep quiet for one reason or another are spared punishment, as public book-burnings and the like are now out of favor. Though disagreement is obviously a fact of life, the evolution of our collective taste has depended on our willingness to call a truce here and there, to accept a compromise, an average, as a plausible guess. Our “civilization,” such as it is, is founded on that practice, and for our personal development and our quest for knowledge, each of us has a stake in it. Knowledge is founded in perception, in the experiences of the senses; they lead us into seeing and understanding relationships, and although the bedrock of our intelligence resides there, only after great difficulty and long ages have we reached consensus on a handful of basic ideas. On the other hand, if we didn’t stay committed to this journey, moving so deliberately forward in our search for those deep connections that constitute knowledge, and if we surrendered entirely to spontaneous feeling right or wrong, we might see the multitudes united, one day, in waves of organic emotional intensity—but they certainly wouldn’t stand the test of time. The fires of such feeling don’t last long, no matter how powerful they seem. From their embers we create a trove of commonplace and mediocre opinion, taken by so many among us as infallible authority.

What then are the real differences between the public for the arts and the public for the sciences—except insofar as the latter group is required to think and analyze objectively, while interpreters of feeling can depend entirely upon their own capacity for response? Think of Sainte-Beuve’s famous response to Chateaubriand as an apologist for faith: “The question isn’t whether something is beautiful; the question is whether it is true.”

Ancient history, which hangs on so stubbornly in our theology, keeps us supplied even today with antiquated constructs of mankind and the world, ideas which most of our contemporaries hold more dear than the firmest of scientific observations. The self-styled critic might be a person of sound judgment; then again, he might not. He might actually know something, or he might be completely ignorant. A gut-feeling judgment can be dead-on; it can also go astray; and in turn it can bring down additional random critiques, which as they heap up high enough can begin to look like consensus or truth. To achieve an “authoritative” view of anything, how much outright ignorance, misinformation, and actual knowledge must go into the recipe?

Throughout Monet’s life as a painter, his public was essentially romantic in its sensibilities, exemplified by that cadre of aesthetes who won’t accept a view of nature that isn’t conspicuously crafted. Of course a human presence is immanent in any effort to interpret experience, reducing the infinite to human scale, transforming the absolute into the relative. Even so, that doesn’t justify all these flourishes of mannerism: reshaping the natural world according to doctrine and personal whim is the stuff of madness; I prefer the old, wise recourse of accepting things as they are.

The public of Monet’s time valued great painters whose handling of light seems far removed from what we see around us every day. Though he needed that public he didn’t bother thinking about it, dedicated as he was to keeping faith with the élan of his own inspiration. Recalling those early sketches of the port at Le Havre, I remember fondly the surprise I felt when I saw sunlight interpreted in a new way, creating a feeling of vibrant truth. There was no way to know as yet what the future would hold for such an eye as this, interrogating the world with an intensity that seemed uncomfortable, even dolorous. So powerful in achieving synthesis, Monet paid the price, analyzing and assembling all the components for these achievements in incandescence. We see this as well in the sketches from his Havrais boyhood, which we will see again soon when they are auctioned off.

I first met Monet in the Quartier Latin. My medical adventures at the Mazas hospital were keeping me busy; he was painting someplace or other, and though we didn’t see each other often, we soon became friends. Mutual acquaintances brought us together from time to time: Paul Dubois, a doctor from Nantes, would be setting up his practice in the Rue de Maubeuge as soon as he graduated; from Castelsarrasin, Antonin Lafont was in the Chamber of Deputies. To these two friends Monet had given some of his seascapes, and already they were saying with a touch of pride, “Ah, that’s a Monet.” Those words meant something, for they caught the surprise, even the wonder, at the courage in the brushwork, still naïve and inexperienced, but sincere in execution, and quick as an expression of will.

When our dear friend Paul Dubois died, a passing I deeply regret, his worldly goods were shipped to the Hotel des Ventes to be auctioned off; and I recall a ripple of astonishment in the audience when some stylish little man, with eyes like black diamonds and a smirk of intense satisfaction, walked away with two Monet sketches for three hundred francs apiece, a bid he had made on the spot even before the auctioneer had called for an opening; the competition, had there been one, would have started at a much lower price. Everyone stared with lively interest at this peculiar-looking Croesus, who left the hall as soon as he had settled his bill, toting off the two pictures he had won without a single bid against him.

Soon, however, we found out who it was: Monsieur Durand-Ruel himself, famous as one of our sharpest experts about painting; his behavior at the auction could be understood only as a resolve to establish, from that day forward, a floor-price beneath which he would not allow an artist he believed in to fall. Durand-Ruel had met Monet in London in 1870; Daubigny had introduced them.

Passionately conservative as he was about nearly everything else, Durand-Ruel was firmly on the side of innovation when it came to painting. In the intrepid skill that made the red smokestacks seem to dance upon the tides at the harbor’s mouth, he had recognized, with his own special awareness for light, the talent from which those ever-changing Meules would eventually come. Swept along by his own infallible taste, Durand-Ruel, as bold in his own way as the artist himself, assumed the role of marketing the young man who would become the most famous member of the school known as “Impressionist,” after a painting of his called Impression, Sunrise.[1] Monet at that time was thirty. The artist and this critic-promoter became close friends, allowing Monet to throw himself entirely into his work and allow inspiration to take him to the heights. Who knows—perhaps it was the hand of Fate that brought this stubborn, dedicated artist into the company of an admirer with such admirable judgment. Without that, perhaps Monet would have seen himself as doomed, heaping up works that would be hailed as masterpieces only after his death. Self-confidence in a genius doesn’t always eliminate, as one might think, a need for approval from others. It’s a matter of degree: though public opinion never figured into Monet’s judgment of his own art, even the greatest painter doesn’t paint for himself alone. And because how we see the world evolves, like all of our other senses, in response to more-or-less intelligent people around us, inevitably some degree of consensus will connect an artist to his time.

The key point is that time for us is life pouring unheeded through the hourglass of constant change, that what is past can never be recovered, that time is the joy we recognize as it flees us in the very moment it appears; and that it is sorrow too, perhaps evaded for now, only to return when we don’t expect it. A man who commits to living according to his own rules is thought of as doing some kind of harm to everyone else. Such loners usually need others to sustain for them a bland and normal life, causing no bother to decent, conventional, harmless people around them. For saving Monet from all those torments, those machinations of coalesced mediocrity, and allowing him to be himself, to stay himself, through thick and thin, Durand-Ruel deserves our lasting thanks. As a dealer he not only helped to keep Monet solvent; he also provided moral support when the struggle for this idealist was at its height, by his side and firmly confident in the future. That consolation was profound, bolstering Monet’s courage in the lifelong project that could sustain itself only by a constant heightening of the risk, and by an understanding that no perfect end was ever possible. The most beautiful success is often hidden in a scrim of reverses; a warrior slowed by his own wounds cannot experience the sweetest triumph—over one’s own self at the end of the day.

When Durand-Ruel bid his three hundred francs for one sketch at the auction, that counted as a true “success” for Monet, for in those early years we saw his paintings on the market for fifty francs apiece. Because a price like that couldn’t include any profit for a dealer, Monet was offering his wares direct to potential buyers. Were there any? Oh, sure: Paris is the city of miracles, and with noisy enemies and credulous disciples, every new movement in thinking finds a welcome there, a chance to classify itself pretentiously as avant garde. Édouard Manet’s name was already making a stir.[2] Others were soon to follow, a wonderful corps of artists who would be the pride of our country: Manet, Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Degas, Jongkind, Caillebotte, Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt. It’s worth remembering that Cézanne encountered some skepticism from Monet himself, though eventually he honored Cézanne by displaying his work at the Giverny house, where important paintings of fellow crusaders were showcased. It can safely be said that the thinking of the Impressionist school, with Monet in the lead, came into prominence in the artistic output of that time.

Nobody could have foreseen that outcome when Monet was going door-to-door hawking his daring work to fans of painting. You could get yourself a genuine Monet for fifty francs, but still there were geniuses out there who refused to buy into this adventure. Some of these hasty works from his youth have survived—and when they turn up on the market, museums compete for them at prices no one could have imagined. In the front rank of the gentry who supported this new school was the famous baritone Faure, cultivating his renown as a connoisseur of painting, a reputation he had worked to build among famous and fashionable coteries associated with L’Opéra. This fine fellow had reached a level where he could indulge himself without risk, and naturally he enjoyed standing out as unconventional in this way or that. Fixing on the Impressionist school as an object for his enthusiasm, he became a defender, and even a “friend” of some of its stars. Having bought some fine Manets without going bankrupt, he bid from time to time on modest works by Monet, as a way of displaying his munificence. Understanding how this worked, Monet, as the pal, would show up from time to time at the home of his celebrity client to offer him paintings at the fifty franc price, which the great man bought when he was in a genial mood. One day Monet came to the door with a single picture under his arm, and Faure was kind and gracious in his greeting. “Glad to see you, dear friend—especially if you’re bringing me a masterpiece.”

“I don’t know about that. I’ve done my best with it.”

“Well, let’s see here. Oh-ho! Well, that won’t do at all, my dear boy. If I buy your work without haggling for it, I expect it to be painted. There’s no paint on this one. You must have forgotten it. The canvas is blank—that’s not good. Take it back and put some paint on it, and I’ll think about buying it… fair enough? … Now just between you and me, what do you suppose this canvas represents?”

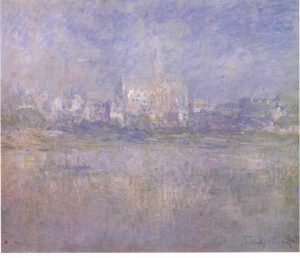

“I don’t suppose, I know that it shows the fog rising from the Seine at Vétheuil. I was out in my rowboat in the early morning waiting for that effect. The sun came up, and—sorry, but I painted what I saw. Maybe that’s why you don’t like it.”

“Oh, right, I get it now. But you have to know it’s the Seine. And when the morning light hits the mist it muddles the view. We can’t see much, but that’s because of the fog, right? … Even so, there’s not enough paint on this canvas. Dab on some more paint and I just might buy it from you.”

Monet took it in stride, headed home, and set the picture in a corner, face to the wall.

Six years after that, in 1879, Monet had a studio where “art lovers” came on visits to buy works for profitable resale in due course. One day Faure himself turned up, looking for something to catch his fancy. Le Lever du Soleil sur Vétheuil was there on an easel.

“Ah, now that’s a lovely work you’ve got there, my friend. Fog in sunlight. The church, turrets, sheds, gleaming cornices breaking through the mist… the village, which we don’t see here, reflected in the stream…. Well, do you want six hundred francs for it?”

Bristling, Monet drew himself up. “So you’ve forgotten that you wouldn’t give fifty francs for that painting six years ago. So now I’ll tell you something: not only will I not let you have it for fifty francs, or six hundred; if you offered me fifty thousand, you still wouldn’t get it.”

Deflated, our baritone went away. What’s lovely about this story is that Le Lever du Soleil sur Vétheuil is still there, for Monet never agreed to part with it.[3] At Giverny, in the ground-floor studio, it’s on the wall for any visitor to see, reminding us of this wonderful story of a rejected canvas.[4] Monet at the time was thirty-three years old: the painting signifies one moment on a hard journey from nothingness to apotheosis, with cruel episodes along the way, thanks to the incomprehension of an oblivious public fancying itself an ultimate judge. This most precious document we have about the growth of this artist, his meticulous study of the subtleties of dispersed light: Le Lever du Soleil sur Vétheuil, with these misty reflections and the brilliance of the sun upon the Seine, heralded the coming of Nymphéas, the curtain-rise at the lily pond.

- Clemenceau remembers the title of this painting only as Impression, and recalls it as a sunset, rather than a sunrise. ↵

- [Clemenceau’s note] Oddly enough, when the Impressionists as a new school were assumed to include Édouard Manet, at first he objected a bit. Having a sharp tongue, he wasn’t a man to hold back with wisecracks: when he learned about the splash that Monet was making, he said, “I don’t know if that fellow will steal my style; but right now he’s trying to steal my name.” ↵

- The painting whose history Clemenceau describes here is Vétheuil dans le Brouillard. Though it remained at Giverny for forty years after Monet’s death, it is now in the Musée Marmottan, Paris. ↵

- Monet’s Vétheuil dans le Brouillard (1879) is now in the collection of the Musée Marmottan, Paris. ↵