Rainbow Unit: Networks Big and Small

4B: Community-Centered Design

Design Introduction

My philosophy is very simple: When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have to stand up, you have to say something, you have to do something.

My mother told me over and over again when I went off to school not to get into trouble but I told her that I got into a good trouble, necessary trouble. Even today I tell people, “We need to get in good trouble.”

John Lewis, interviewed by Valerie Jackson for StoryCorps[1]

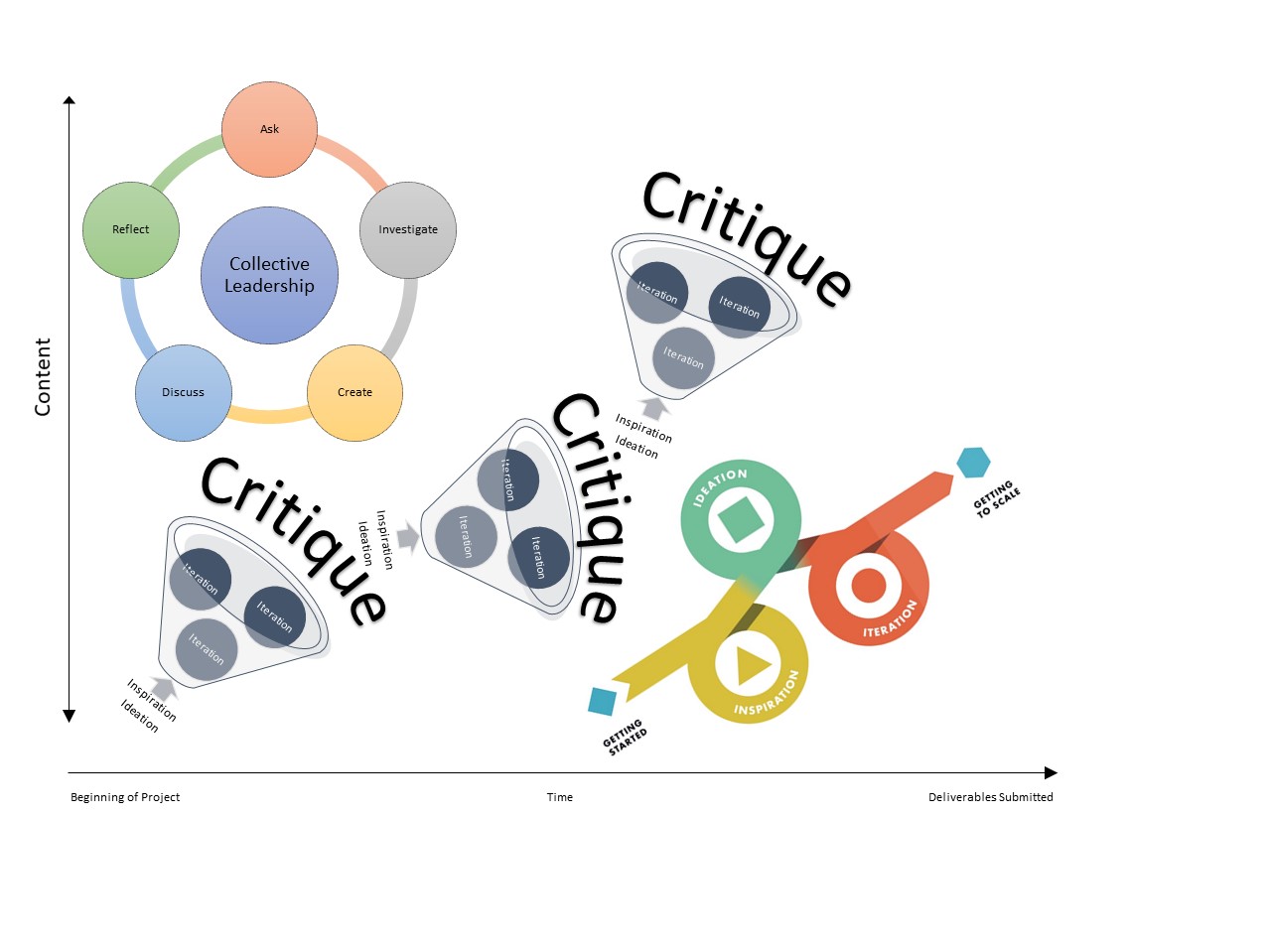

In this concluding session of the Rainbow Unit, we have begun by exploring some ways design can be used to recover community through design thinking, design justice, and the community informatics design studios and design for values approaches. These are an essential part of working towards “good trouble.”

Returning now to your chosen person-centered networked information systems adventure from session three, what design considerations need to be (further) integrated into the inspiration, ideation, and iteration process to more deeply foster and embed a person-centered community technology design so as to truly incorporate a design justice framework?

The Lesson Plan for this session lists a number of design process materials and design case study resources within the Essential Resources section. In session three you chose your own adventure based on your focus formulation and information collection goals. In this session, use these Essential Resources as a starting point for considering effective ways you would add design into these adventures.

The sixth and final stage within Carol Kuhlthau’s information search process is presentation, which leads to feelings of satisfaction or disappointment through actions of documenting. When this presentation stage is brought into the recurring process of the design critique, this sixth stage helps to further refine and/or redirect stages four and five of the information search process, further advancing the overall design process at the same time. Let’s bring all this together with a design critique exercise.

The Design Critique

Design Justice: the importance of merging community informatics studio, community inquiry, and collective leadership with design thinking.

As noted in the first part of this session, critique is an essential, rigorous form of evaluation within design, something used throughout the design process. There are many different forms from very informal peer critiques to formal evaluation events. For this exercise, an initial 3-person critique would be ideal. If you are in a space in which there are at least three different design teams working on different person-centered network information system adventures, this would be the highly recommended option. But in all contexts and spaces, some form of informal sharing and feedback request serves as a very important generative tool in the design process.

Steps

- Before entering into a peer critique, gather as a team to reflect on the current cycle of design.

- What are the overall outcome objectives of this design adventure? What are some of the shapers that have led to these goals?

- What inspirations and ideations shaped the iteration processes of the current design cycle. Which of the iterations were left behind before testing was done? What iterations were very briefly tested? What iterations continued moving forward?

- What aspects of the community inquiry cycle were incorporated into this design cycle beyond creation of prototypes? Who served in leadership during the community inquiry process?

- What design approaches were used within this cycle of design? Some to consider include: user-centered design, human-centered design, value-sensitive design, universal design, inclusive design, participatory action research/participatory design, transformation design, and social implication design.

- What design techniques beyond those specific to those we’ve incorporated to date centered around hardware, software, and networks, were incorporated within this cycle? These might include: form, composition, balance, typography, visual literacy, color theory, among others.

- Peer critiques are informal, but that doesn’t mean they are unstructured. With these reflections in hand, create the structure and scaffolding by preparing a five-minute design pitch strategically bringing these reflections together in a way that facilitates effective feedback. Given its informality, a slide deck and presentation notes are generally not needed in this form of critique.

- If this is a 3-person peer critique, the next step is to gather with two other people, each from a different team.

- One team member begins with their five-minute pitch and feedback request.

- After the five-minute pitch, the two others then ask for additional details and clarifications over the next five minutes.

- For the third five-minute period, the first person turns their back to the other two to assure they only take notes while the other two members provide a critique of the design inspiration, ideation(s), and iteration(s) presented initially.

- The peer critique of presenter one finishes with five minutes of open discussion.

- Member two then has 20 minutes to repeat the process used for member one. This is then repeated one last time with member three.

- There are many physical and online spaces in which we have an opportunity to enter into informal sharing and feedback. There may be patrons with whom you regularly chat and so may have an opportunity to bounce some ideas off them in a more structured way to get helpful critique. There may be opportunities for staff gatherings to bring this into the work community of practice. Teen spaces, especially when developed to include a teen advisory group, are often a great resource for peer critiques, as are other advisory groups. Use the steps listed above as a starting point for setting up the structure to be used in these and other alternative peer critique spaces.

- If this is a 3-person peer critique, the next step is to gather with two other people, each from a different team.

Regardless of the path chosen, there is great value in bringing multiple peer critiques back to the team for review and the launch of the next design thinking cycle.

- As design cycles continue, it’s highly recommended that desk and seminar/group critiques also be brought into the larger design process.

- In desk critiques, instructors, teaching assistants, and/or mentors come together to model cognitive, socioemotional, and critical social + technical skills along with professional practice. The team meets in person or online with those leading the desk critique, providing a five- to 10-minute presentation. The rest of the critique is more flexible to assure highly generative modeling.

- In seminar and group critiques, the class as a whole, potentially joined by a juried panel, view a structured and summative presentation by the team using a symposium format. When a juried panel is in attendance, they first provide a more formal peer-review to further development of ideas and product deliverables as well as to provide evaluative feedback. In addition, all in attendance provide additional development of ideas and product deliverables as a group.

Diving Deeper

For there to be design justice, it is important to consider all ways possible to bring diverse community knowledge and cultural wealth to bear in the process. Indeed, as we’ve seen throughout the textbook, innovative design and redesign of technologies so often forces into hiding the expansive, diverse works of design and creation of technology done by each human. As Costanza-Chock notes:

Design justice as a framework recognizes the universality of design as a human activity. As noted in the introduction, design means to make a mark, make a plan, or problem-solve; all human beings thus participate in design. However, though all humans design, not everyone gets paid to do so. Intersectional inequality systematically structures paid professional design work. Professional design jobs in nearly all fields are disproportionately allocated to people who occupy highly privileged locations within the matrix of domination. At the same time, the numerous expert designers and technologists who are not wealthy and/or educationally privileged white cis men have often been ignored, their labor appropriated, and their stories erased from the history of technology.[2]

Sasha Costanza-Chock, Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need

As information science professionals, we are paid not to just passively and strictly follow a list of tasks verbatim, but to creatively innovate-in-use our designated activities in ways that meet the needs of our patrons. If we are to truly advance stated and emerging social justice parameters within our profession, we first need to move from user-centered design to human-centered design as part of our daily practices. But from here, we need to also move from general design thinking to an essential design justice framing. Funding to pay community members as members of the design team is an essential feature to advance social justice objectives, but one too often difficult to carry out in practice. In addition, many designers have other commitments to work, community, and family that keep them from daily participation. I’ve found at times an effective middle ground is to embed collective leadership within this process through invitation (with provision of funds, transport, and food to every extent possible) of community members who bring essential community knowledge and cultural wealth to bear within the critique process itself.

Wrap Up

Many technical instructions leave unconsidered the embedded social dimensions of technologies that are continuously in tension with the limits and constraints to social justice parameters. Unconsidered, we likely further algorithms of oppression in our personal and professional practices. This is also true of design processes, and is why design justice has been emphasized so strongly throughout session four. And as noted in the session three Wrap Up, if you currently do not have rich diversity within your community of practice, work to outline clearly how diversity would be brought into the collective leadership to assure this is the “good trouble” to which the late John Lewis refers.

Comprehension Check

Return again to the comprehension check you developed for yourself at the end of session three. Take some time now to add to this some specifics related to design. What are the specific design-centered comprehension checks you are seeking to assure are reaching the “yet enough” point of introductory development?

- John Lewis and Valerie Jackson, “The Boy From Troy: How Dr. King Inspired A Young John Lewis,” StoryCorps, February 20, 2018. https://storycorps.org/stories/the-boy-from-troy-how-dr-king-inspired-a-young-john-lewis/. ↵

- Sasha Costanza-Chock, Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need, Information Policy (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020), 73. https://design-justice.pubpub.org/. ↵