Orange Unit: A Person-Centered Launch

2A: Critical Social + Technical Perspective

Background Knowledge Probe

- In what ways have you been shaped by technology? When, where, how, and why?

- In what ways have you helped to shape technology? When, where, how, and why?

- In what ways have the people closest to you been shaped, positively and negatively, by this shaping of technology? When, where, how, and why?

Community Inquiry as the Basis for Digital Literacy Radically Reconsidered

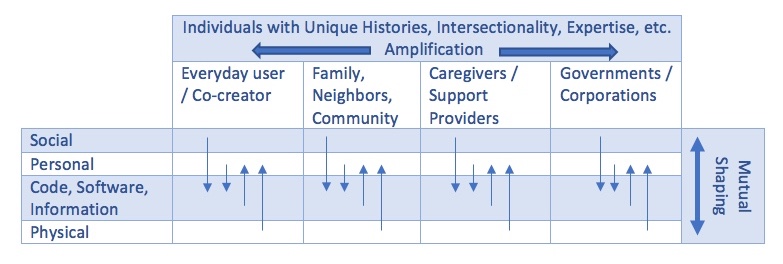

Literacy is a set of competencies and knowledge within a certain domain. Digital literacy, then, is literacy within the realm of digital information and communication technologies. Summarizing a variety of definitions regarding digital literacy and related computational thinking, this set of competencies includes:

- Technical skills: The ability to appropriately select and effectively use a range of technologies.

- Information skills: The ability to seek, evaluate, interpret, and apply relevant and trustworthy information across multiple media.

- Cognitive skills: The ability to logically analyze and organize problems in ways that allow use of digital and other tools to help solve them and to generalize new processes to other problems.

- Socio-emotional skills: The ability to communicate and collaborate with others, along with the personal confidence, persistence, and tolerance needed to tackle complex, ambiguous, and open-ended problems.

- Application skills: The ability to integrate the above skills into our everyday experiences in order to advance our professional, personal, and civic interests and responsibilities.

If we are to assure active participation in civic society and meaningful, diverse and inclusive contributions to vibrant, informed, and engaged community, it is essential to add the social justice-oriented progressive community [inter]action and critical social + technical skills to these other five points.

- The critical social + technical skills are brought forward as part of person- and community-centered deliberative dialogue processes using critical research paradigms, pedagogies, and abductive reasoning in combination with each of the five commonly considered digital literacy skills listed above.

- Progressive community [inter]action skills are simultaneously used in combination with the starting five digital literacy skills by advancing our ability to work together in communities of inquiry that make continued use of collective leadership, functional diversity, members’ capability sets and freedom of choice to better achieve valued beings and doings, community cultural wealth, and care work and ethics.

Whether as part of preprofessional and professional development of library and information management workers, or as part of programming offered by these professionals, a radical reconsideration of digital literacy is essential if we are to effectively use sociotechnical products to amplify human forces which advance human and community development. This social-forward approach to digital literacy training doesn’t negate learning about the nuts and bolts of the hardware and software. It instead works to advance our critical social + technical skills so as to situate such learning within the individual and group goals and values.

A Person-Centered Approach to Digital Literacy

Strategies

- Meet with stakeholders to understand what creative works participants would like to do and what digital technologies might be needed to do them.

- Incorporate digital literacy training as infill into projects as needed.

- Include exercises exploring all dimensions of socio-technical artifacts.

- Intersperse discussion and critical reflection with hands-on activities to bring to the fore participants’ human and social expertise to complement hardware and software skills development.

Goals

- Achieve the creative works as determined by participants during stakeholder meetings.

- Advance participants’ capability set (the increased existence, sense, exercise, and achievement of choice).

- Increase participant’s ability to select and appropriate strategies/technologies that align with their values and goals.

- Counter the dehumanizing impacts of digital technologies.

- Work towards the essential outcome of more resilient, inclusive, and just communities.

Values

Technology is shaped by and shapes society. From this starting point, we posit that:

- The social, cultural, historical, economic, and political values and practices of stakeholders at each point in an artifact’s life cycle tend to become embedded within that artifact.

- There are exclusionary social structures, some of which we actively — even if unintentionally — reinforce through our choices and actions regarding technology creation and use.

- Digital literacy without a critical and sociotechnical perspective is at risk of fostering magical thinking and technological utopianism.

- A liberative approach to technology requires lived and academic expertise within multiple domains, including hardware, software, human, community, social, cultural, historical, political, and economic.

Key Takeaways

- Those of us with technical expertise may enter into an engagement as digital literacy instructors, but we also need to be willing learners if we are to understand the exclusionary social structures embedded within sociotechnical artifacts and thereby champion justice.

- The digitally excluded and participants from the margins of society may enter into digital literacy training as learners, but also bring essential sociotechnical expertise and teaching to communities of inquiry.

- Difference is not just a nicety, but an essential resource in building more resilient, inclusive, and just communities.

Advancing digital inclusion, equity, and literacy often presents unique information needs and potentially burdensome financial, human, and infrastructure challenges. Partnerships among stakeholders, including those from the information sciences and information management, often serve at the front lines to mitigate these challenges. But how do we best help organizations build the capacity to meet the information needs of communities? In what ways can we develop 21st century skills to foster individual, social, and economic development? How can we integrate standards and frameworks such as collective leadership, community inquiry, action-reflection cycles, information seeking, studio-based learning and design thinking, collaborative programming and computational thinking, and creativity, play, and tinkering into the partnership process?

Lesson Plan

While the focus of the technical chapter, “Electronic Components in Series,” is on how we can reuse the LEDs and resistors in combination with momentary switch push buttons, it is important for us to also continually reflect on the social aspects of these sociotechnical artifacts. Our educational and professional systems are built so as to often separate these two aspects. How can we work together in this session and in each of the following sessions to identify ways in which mutual shaping and amplification of sociotechnical artifacts has happened or is happening with this moment? How are we working to further the gendering of the artifacts? How are we working to problematize these artifacts so as to advance a more person-centered approach?

Essential Resources:

- Toyama, Kentaro. “TEDxTokyo – Kentaro Toyama.” YouTube, May 10, 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cxutDM2r534.[5]

- Oxford Internet Institute. “OII Awards 2018: In Conversation with Judy Wajcman.” YouTube, November 26, 2019. https://youtu.be/pf7-93ioYsE.

Additional Resources:

- Bruce, Bertram C., Andee Rubin, and Junghyun An. “Situated Evaluation of Socio-Technical Systems.” In Handbook of Research on Socio-Technical Design and Social Networking Systems, edited by Brian Whitworth and Aldo de Moor, 2: 685–98. Information Science Reference. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2009. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/9710.

- Fischer, Gerhard, and Thomas Herrmann, “Socio-Technical Systems: A Meta-Design Perspective,” International Journal for Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development 3, no. 1 (2011): 1–33.

- Wajcman, J. “Feminist Theories of Technology.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34, no. 1 (January 1, 2010): 143–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/ben057.

Key Technical Terms

- Closed and open running in and

- Key conductive materials such as and

- Key electronic components, including , , and , which include both and legs

- Educationally defined skillsets necessary for individual and collective sociotechnical innovation in the real world, including technical, information, cognitive, socio-emotional, application-based, critical, and progressive community interaction skills

Professional Journal Reflections:

- How would you have described the terms digital technology, digital literacy, and digital innovation prior to reading this chapter and related resources? What are some of the contexts leading you to these initial descriptions?

- What are some of the different descriptions of the terms that come forward through the reading of this chapter and related essential resources? What are some of the contexts shaping the authors of these descriptions, and the contexts shaping your understanding of their descriptions?

- What are some of the different ways you’ve learned about networks, information systems, and digital technologies as part of your lived history? How has that influenced your sharing of knowledge and best practices with others? How might we work together throughout this book to teach and learn together about systems in ways that foster sustainable development?

- From your lived experiences and reading of text and context coming into the reading of the book and in your works so far through the book, in what ways have deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning, and/or abductive reasoning played a role in shaping the creation and marketing of electronic technology around you? Your selection, use, and innovation-in-use of that technology?

- Wajcman, Judy, “Feminist Theories of Technology,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34, no. 1 (January 1, 2010): 143–52. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-264-0.ch045. ↵

- Bruce, Bertram, Andee Rubin, and Junghyun An, “Situated Evaluation of Socio-Technical Systems.” In Handbook of Research on Socio-Technical Design and Social Networking Systems, edited by Brian Whitworth and Aldo de Moor, Information Science Reference (Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2009), 2: 685–98. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-264-0. ↵

- Fischer, Gerhard, and Thomas Herrmann, “Socio-Technical Systems: A Meta-Design Perspective,” International Journal for Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development 3, no. 1 (2011): 1–33. https://doi.org/10.4018/jskd.2011010101. ↵

- Rhinesmith, Colin, and Martin Wolske, “Community Informatics Studio: A Conceptual Framework.” In CIRN Community Informatics Research Network Conference: “Challenges and Solutions,“ Prato, Italy: Centre for Community and Social Informatics, Faculty of IT, Monash University, 2014. https://shareok.org/handle/11244/13631. ↵

- TED Talks are licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. ↵

When working with electrical components, a circuit is the complete path that allows an electric current to flow from source voltage back to the source ground. Circuits generally include one or more electrical components along this path which are powered by the source.

A closed circuit is one in which current can flow fully from its source voltage to its ground return uninterrupted.

An open circuit is one in which there is an interruption in the flow of current from its source voltage to its ground return.

A complete, closed circuit in which there is one path along which current flows. When one electronic component along the path fails or is interrupted in some way, all components enter an open state and stop working.

A complete, closed circuit in which current divides into multiple paths to ground. A failure on one path does not impact electronic components passing along another path running in parallel.

A breadboard used to be a board (sometimes literally a board for cutting bread) with nails pounded into it so that you could wrap wires around them to make experimental models of electric circuits. Today, the breadboard is a piece of plastic with holes in it. Underneath each hole is a metal clip. These metal clips connect together a specified set of holes ordered into a row or column. This way, pushing a piece of conductive material into one hole right away connects that material to things pushed into other holes that are joined together by that clip.

A perfboard is a thin, rigid sheet with holes but no metal clips on the other side. Instead, copper pads are used, to which conductors can be soldered. In some cases, as with the perma-proto breadboards from Adafruit, copper is further used to group together certain holes, mimicking the breadboard in a way that provides greater durability for prototyping work.

Wires are made of either a thicker solid metal or thinner strands of multiple wires, placed within a non-conductive material. The exposed ends of the wire can then be inserted into two different holes on the breadboard to safely conduct current from one hole to another, helping to extend the circuit between different electrical components. These are sometimes attached to a plastic holder to provide greater strength. If a solid metal wire end has been soldered into the other side of that plastic holder, it is known as a male end. If a metal wire can be temporarily inserted into the other side of that plastic holder, it is known as a female end. If a pair of metal clips attached with springs is provided, it is known as an alligator clip.

Electrical resistance reduces the flow of current through a circuit. Resistors are the typical electrical components used to provide resistance in a circuit, and are listed in ohms. For instance, the exercises in the book mainly use 470- or 560-ohm resistors, also abbreviated as 470 Ω or 560 Ω resistors.

Electronic switches are used to control the flow of current on a circuit. They can be used to switch between the closed position, in which a current continues its flow through a circuit, and the open position, in which the current is not passed through. A classic example of this type is a light switch, in which a closed position would turn on a light and an open position would turn off that light. Closing the switch completes the circuit. Other switches are used to control the amount of current that flows across the circuit. A classic example of this type is a dimmer switch for a light used to brighten or dim the brightness of a light.

While the above are common mechanical switches, it is also possible to use programming code to switch the flow of current along a circuit. A common method for doing this is through use of a transistor, which uses a low current signal to one leg of the transistor provided by the program to determine the flow of a larger amount of current through the transistors other two legs.

A semiconductor that passes current from one terminal to another terminal and in which current can only flow in one direction, known as rectification. Some common uses of diodes include reverse current protection, to clip or clamp circuits, and to provide logic gates. Another common usage is as a source for generating light, known as a Light-Emitting Diode, or LED. Different LEDs work at different wavelengths (the measure of distance between the peak and the trough in a wave), associated with different recognized colors of light. Some LEDs are made to be especially bright, such as a car headlamp made to help us see the road more clearly. Others are meant to be more diffuse, thereby working more as a source of information, like a car brake light or turn signal. Multiple light-emitting diodes can be packaged together in groups of three that include a red, a green, and a blue LED. These RGB LEDs can be further packaged together to create a full LED matrix display.

The positively charged electrodes conducting electric current from a cell into a device like a diode.

The negatively charged electrodes conducting electric current out of a device, like a diode, and back to a cell.

![The seven essential skills of digital literacy include information skills, cognitive skills, socio-emotional skills, application skills, progressive community [inter]action skills, and critical social + technical skills](https://iopn.library.illinois.edu/pressbooks/demystifyingtechnology2/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2022/06/RadicalReconsiderationOfDigitalLiteracyGraphic_cropped.jpg)