Orange Unit: A Person-Centered Launch

4A: Storytelling in the Information Sciences

Yingying Han and Martin Wolske

Storytelling’s Long History in the Information Sciences

Many of us may have the childhood experience of sleeping while a family member tells us a bedtime story. But if we look more closely, we’ll find that storytelling is a ubiquitous practice in our daily lives. The goal of storytelling is “to be able to create a story, to make it live during the moment of telling, to arouse emotions—wonder, laughter, joy, amazement”[1].

Storytelling has a rich history in the library and information sciences (LIS), dating back to the 1890s when it was established as a practice in youth services librarianship[2]. For example, the Urbana Free Library, a public library east of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign campus, hosts regular storytelling sessions for children, attracting many local families. The Urbana Free Library also collaborates with the East Center for East Asian and Pacific Studies at the University to host East Asian story time, providing a valuable resource for young people interested in East Asian culture.

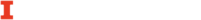

In her paper “Storytelling wisdom: story, information, and DIKW,” Kate McDowell notes that “LIS storytelling emphasizes a triangular relationship between teller, audience, and story, a dynamic process that co-creates a particular telling of a story.” At its best, it is a mutual creation as the three relationships inform each other. The dynamic relationship has three main elements: “For storytelling to occur, there must first be a basic relationship of trust between the teller and the audience. […] Second, the teller has a relationship to the story, whether as creator or reteller. […] Third, the audience has an interpretive relationship to the story” (p. 1224, emphasis by author).”

As we explored in the Orange Unit 3A: The Unknown Tech Innovators, there are a range of unknown innovators of our everyday technologies. In some cases, this may be by choice of the innovator to not tell their story, as such effort isn’t part of their community cultural wealth, or maybe because such effort would compete with their time dedicated to other purposes. But as Bruce Sinclair notes, the stories regarding innovators and innovations often prioritize the work of engineering over that of crafting[3]. Carolyn de la Peña further highlights how the papers and records of such innovation stories are often restricted to those of white men[4]. As we look across the dynamic triangle and consider its three main elements, it is essential for us to add this further lens that inevitably shapes the story, storyteller, and audience in a variety of ways.

Stories transform in many different ways depending on when and where they are told, whether at a fireplace or in cyberspace, to a young person or to a senior. Storytelling serves an essential role in its relationship to story and to audience. Strategically reaching target audiences in ways that encourage them to move from the role of receiver to that of collaborator within a collective meaning-making process is then a way to counter the dominant narrative that Sinclair and de la Peña describe.

Storytelling polishes stories like editing polishes essays, with the audience serving as editor. Changes add collective understandings to the story by emphasizing particular words, characters, actions, and more. Audiences interpret stories as groups, socially constructing meanings. Retellings demonstrate how a story can be told so that others also recall and retell, and the story keeps traveling. “Stories live everywhere, but they rarely stay in one place” (Hearne, 1997).[5] Storytelling entails dynamic collective interpretation, both synchronous and across long spans of time. So what is a story?

Story is here defined in two ways: structurally as narratively patterned information, and functionally as the content shared through the narrative experience of storytelling.

McDowell, p. 1225[6].

The Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom Pyramid

At the start of the Orange Unit 1A: Information Systems, a connection was made between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom, the pyramid of which “has proved very useful in the information sciences as a means of investigating how different aspects of this pyramid have influenced the shaping of individuals, communities, societies, organizations, and governing bodies.” This can also be incorporated specifically into storytelling concepts, which we’ll explore in a minute.

But first, let’s pause to further clarify the definitions of Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom (DIKW) within the pyramid.

According to Merriam-Webster, data is information in digital form that can be transmitted or processed. For example, if I ask you what the following list of numbers means—01001001 01010011 00100000 00110100 00110000 00110001 00100000 01010010 01101111 01100011 01101011 01110011 00100001—you probably will be confused for a while. What if you were given more context, being told this is a binary number that can be translated into English texts and Roman numerals through an ASCII table? You can use either an ASCII table or use a Binary-Text translator (for example, Convert Binary) to find that the 13 sets of 8-bit data are translated into the text “IS 401 Rocks!”, where 01001001 = the capital I, 01010011 = the capital S, 00100000 = a space character, etc.

In her article “The wisdom hierarchy: representations of the DIKW hierarchy,” Rowley refers to information as “organized or structured data which has been processed in such a way that the information now has relevance for a specific purpose of context and is therefore meaningful, valuable, useful and relevant.”[7]” People may extract different meanings from the information “IS 401 Rocks!” depending on the context.

Starting with the first two text elements, look up IS in Merriam-Webster, and you’ll find these two letters in capitals means “Information System.” But this is not necessarily what the creator of the binary numbers meant. For one major target audience of this textbook, however—students at the School of Information Sciences, the iSchool at Illinois—“IS 401” is the course number for the course Introduction to Network Information Systems. Until knowing this context, it might be hard to truly move the binary data to text and then on to information.

Turning to the third element within the text, many English speakers within the United States would hopefully recognize “Rocks” in this context not as a statement regarding the relationship between this course and a solid mineral matter, but rather as a proposed statement of excitement regarding the course IS 401. For people for whom English is not their primary language, or who understand the language within different social and cultural contexts, “IS 401 Rocks!” is not meaningful information because they will not be able to interpret it.

Take a moment to consider how two different students, one a third-generation U.S. citizen and one from Asia for whom English is their second language, would interpret the answer “IS 401 Rocks!” to their question, “How was IS 401 when you took it?” If understood to be a course that is exciting to take, the information becomes “actionable information,” that is, knowledge, that the course should be something to consider registering to take. But for others the response may be confusing or misleading, and may result in knowledge regarding a low-quality course for which it would be wrong to take. Here we can see that travel along the DIKW pyramid can take different paths. As McDowell argues, in “uncertain, conflictual, or paradoxical situations, knowledge of how to accomplish tasks is not enough. We need wisdom.”[8]

Defining wisdom is hard. According to Rowley[9], wisdom is accumulated knowledge that allows you to understand how to apply concepts from one domain to new situations or programs. For McDowell, wisdom may be similar to being a storyteller whose action occurs in context. “[W]isdom may be socially constructed and enacted situationally. If wisdom is enacted, then it can be the province of groups as well as individuals.”[10] LIS scholars have long been interested in studying the wisdom of collective information sharing, for example when using Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) to share collective information during a crisis.

So, where does the story fit in this pyramid? Below is the Story-DIKW framework proposed by Kate McDowell:

- S-Data: Ability to identify and interpret data from which information emerges that can be communicated in story.

- S-Information: Ability to inform audiences by communicating data with context as story, in both form and narrative experience.

- S-Knowledge: Ability to convey knowledge as complex actionable information through the construction and telling of a story, incorporating cultural and contextual cues. S-knowledge is shared frequently in innovative or experimental contexts.

- S-Wisdom: Ability to know which story to tell—including when, how, and to whom—in order to convey wisdom.

Take a few minutes to reflect back on your journey through the Orange Unit of this textbook. In what ways, if any, might it fit within the dynamic triangle of story, teller, and audience? In what ways, if any, might various aspects fit within the data, information, knowledge, and wisdom pyramid of the S-DIKW framework?

Social Justice Storytelling: Why It Matters

Memory institutions such as libraries and archives in the United States have a long history of excluding and erasing cultures of people who are marginalized.[11][12] For example, Sutherland[13] argues that by failing to create an official record of human rights abuses in the United States, American archivists have continued to perpetrate violence against Black Americans by failing to tell Black Americans’ stories. This century-long refusal to engage justice for Black Americans endures in present-day through archival professions in the United States.

Digital storytelling is a technique that allows the story to be retold even while the storyteller is sleeping. This technique also allows the storyteller to use additional media to better bring home the moment. It is an innovative, community-based, participatory research technique bringing together community members and health workers to approach, research, and collaboratively address local health issues.[14] It has been incorporated into traditional quilting, along with capacitive touch sensors, to create living archives of voices in the sex work industry.[15] It has played a role in co-design initiatives involving local underserved communities in data generation, and in spurring grassroots initiatives and encouraging broader local participation and engagement in community-based co-design projects.[16]

Social justice storytelling is an essential approach emerging within the Information Sciences as the profession works to give voice to people who are marginalized. Communicating in culturally competent ways about social justice as information professionals requires that training in this area be brought into the classroom as well[17]. Counterstorytelling is one of the primary tenets of critical race theory[18][19][20] and involves telling stories that “buck the status quo and challenge the long held collective stories of a hegemonic society, which tacitly maintain the narratives and normative behavior of dominant groups.”[21] Counterstorytelling is thus proposed as a key approach to social justice storytelling in the information sciences generally,[22] and in our work through this textbook as a community of practice seeking to bring a more holistic and nuanced understanding of sociotechnical artifacts we use as a daily part of our professional lives specifically.

For the first edition of A Person-Centered Guide to Demystifying Technology, Cooke’s chapter “Becoming New Storytellers: Counterstorytelling in LIS”[23] was foundational in guiding this final session of the Orange Unit. McDowell’s writing on storytelling and DIKW, including her article co-authored with Cooke on social justice storytelling, were published between editions of this textbook and strongly build off of Cooke’s previous foundational work. For Cooke, becoming a “new storyteller” is a call for us to take on an active information professional leadership role, facilitating discussions on issues of race, privilege, social justice, and other necessary and difficult issues. Becoming new storytellers has provided further clarity and a more solid foundation for the many different participatory action research and course offerings that have now come together to create A Person-Centered Guide to Demystifying Technology. The previous sessions of the Orange Unit are thus not separate from this social chapter of session four, but serve as precursors to this chapter. And this final session of the Orange Unit itself serves as not only a conclusion of this first unit, but also as the base for the Blue and Rainbow Units, as each seeks to facilitate a collective journey to becoming new storytellers within the Information Sciences.

Digital technologies old and new are not objects that can be packed inside a box. They are a seamless, indivisible combination of people, organizations, policies, economies, histories, cultures, knowledge, and material things that are continuously shaped and reshaped. Every one of us innovates-in-use our everyday technologies; we just do not always know it. Not only are we shaped by the networked information tools in our midst; we also shape them and thereby shape others. For us to advance the individual agency of all drawing upon diverse community knowledge and cultural wealth within the fabric of communities, we need to nurture our cognitive, socio-emotional, information, and progressive community engagement skills, along with, and sometimes in advance of, our technical skills, which then serve as just-in-time in-fill learning. This is the call placed by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—to rapidly shift from a “thing-oriented” society to a “person-oriented” society.[24]

One step in this, then, is to become new storytellers regarding sociotechnical artifacts and systems, including within a broadened conceptualization of networked information systems. Stock stories abound, bringing us into dominant narratives around the importance of technologies in changing society. It removes from the story the centrality of people, race, privilege, and power, which are used to shape the technology and its narrative. In this removal, many lose individual sociotechnical-related agency, and in addition often lose aspects of their human rights. How we buck the status quo through counterstories varies as we work to assure the right story, at the right time, in the right way, using a dynamic storytelling triangle. Forms of counterstory include: a concealed story that serves as a direct response to stock stories, a resistance story that not only bucks against stock stories but also highlights injustices, or an emerging/transforming story that (re)constructs knowledge built on concealed and resistance stories.[25]

Lesson Plan

We will continue to develop the full range of our technical, information, cognitive, socio-emotional, and application skills moving forward. But as has been noted throughout, to advance a person-centered and social-justice-oriented approach to demystifying technology, we also need to actively bring in progressive community [inter]action and critical social and technical skills to these other five points. Storytelling for social justice is meant to serve as an active way to bring each of these together, starting with this session. At the same time, we will continue to advance various others of our skillsets as we Meet the Microcomputer and Get Started with the Raspberry Pi, before moving on to explore Coding Electronics. It is hoped that these will facilitate a solid step forward as we work to evolve a more holistic and nuanced understanding of the sociotechnical artifacts we use as a daily part of our professional lives.

Essential Resources:

- McDowell, K. “Storytelling wisdom: Story, information, and DIKW.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 72 (10) (2021): 1223–1233. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24466

- Lorini, Maria Rosa, Amalia Sabiescu, and Nemanja Memarovic. “Collective Digital Storytelling in Community-Based Co-Design Projects: An Emergent Approach.” The Journal of Community Informatics 13, no. 1 (2017): 109–36. https://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v13i1.3296.

Additional Resources:

- Cooke, Nicole. “Becoming New Storytellers: Counterstorytelling in LIS.” In Information Services to Diverse Populations: Developing Culturally Competent Library Professionals, 113–36. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2017.

- StoryCorps is a nonprofit with a mission “to preserve and share humanity’s stories in order to build connections between people and create a more just and compassionate world.”

- StoryCorps. “The Great Thanksgiving Listen.” Accessed February 10, 2020. https://storycorps.org/discover/the-great-thanksgiving-listen/.

- StoryCorps. “StoryCorps DIY.” Accessed February 10, 2020. https://storycorps.org/participate/storycorps-diy/.

- Wolske, Martin. “Digital Storytelling Workshop.” Presented at the Faculty Summer Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2011. https://uofi.box.com/s/77jgdy33acn6ezsllqh87472xnux9d56.

- Gubrium, Aline. “Digital Storytelling: An Emergent Method for Health Promotion Research and Practice.” Health Promotion Practice 10, no. 2 (2009): 186–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839909332600.

- Crane, Beverly. “Digital Storytelling Changes the Way We Write Stories.” Information Searcher 18, no. 1 (2008): 3–9, 35.

- Drotner, Kirsten. “Boundaries and Bridges: Digital Storytelling in Education Studies and Media Studies.” In Digital Storytelling, Mediatized Stories: Self-Representations in New Media, edited by Knut Lundby, 61–84. New York: Peter Lang, 2008.

Key Technical Terms

- Core hardware components of a computer, including the system board/motherboard, the central processing unit and other controllers, types of short-term memory and longer-term storage, and input/output devices.

- How the above is implemented in practice within a system-on-a-chip microcomputer, using the Raspberry Pi as an example.

- Core software components of a computer operating system, including the kernel, window system, desktop environment, and top-level themes and skins.

- How the above is implemented in practice within the Raspberry Pi OS, a distribution based on the underlying Debian GNU/Linux operating system.

Professional Journal Reflections:

Dedicate some time to using your Professional Journal Reflections forum to post two or three short, partial drafts of counterstories that you can share with others. You might draft the same story told to different audiences, different stories told to the same audience, or other mixes as you see fit. Drafts should rough out:

- How the story would build towards the key moment

- Introduction of location, characters, and questions/conflicts/challenges

- Main course of events

- Conclusion revealing what happened and its meaning

- Sawyer, Ruth. The Way of the Storyteller. New York: The Viking Press, 1942. ↵

- McDowell, Kate. “Storytelling wisdom: Story, information, and DIKW.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 72, no. 10 (2021): 1223–1233, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24466. ↵

- Sinclair, Bruce. “Integrating the Histories of Race and Technology.” In Technology and the African-American Experience: Needs and Opportunities for Study. Boston: MIT Press, 2004. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262195041/. ↵

- Peña, Carolyn de la. “The History of Technology, the Resistance of Archives, and the Whiteness of Race.” Technology and Culture 51, no. 4 (October 2010): 919–37, https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2010.0064. ↵

- Hearne, Betsy. “Story, from fireplace to cyberspace: Connecting children and narrative.” In B. G. Hearne (Ed.), Allerton Park Institute 39th (p. 143). Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science, 1997. ↵

- McDowell, Kate. “Storytelling wisdom: Story, information, and DIKW.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 72, no. 10 (2021): 1223–1233, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24466. ↵

- Rowley, Jennifer. “The wisdom hierarchy: Representations of the DIKW hierarchy.” Journal of Information Science, 33, no. 2 (2007): 163–180, https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551506070706. ↵

- p. 1227, McDowell, Kate. “Storytelling wisdom: Story, information, and DIKW.” ↵

- Rowley, Jennifer. “The wisdom hierarchy: Representations of the DIKW hierarchy.” ↵

- p. 1229, McDowell, Kate. “Storytelling wisdom: Story, information, and DIKW.” ↵

- Caswell, Michelle. “Seeing yourself in history: Community archives and the fight against symbolic annihilation.” The Public Historian, 36, no. 4 (2014): 26–37, https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2014.36.4.26. ↵

- Caswell, Michelle., Marika Cifor, & Mario H. Ramirez. “’To suddenly discover yourself existing’: Uncovering the impact of community archives.” The American Archivist, 79, no. 1 (2016): 56–81, https://doi.org/10.17723/0360-9081.79.1.56. ↵

- Sutherland, Tonia. “Archival amnesty: In search of Black American transitional and restorative justice.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1, no. 2 (2017), https://doi.org/10.24242/jclis.v1i2.42. ↵

- Gubrium, Aline. “Digital Storytelling: An Emergent Method for Health Promotion Research and Practice,” Health Promotion Practice 10, no. 2 (2009): 186–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839909332600. ↵

- Strohmayer, Angelika and Janis Meissner. “‘We Had Tough Times, but We’ve Sort of Sewn Our Way through It’: The Partnership Quilt,” XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students 24, no. 2 (December 19, 2017): 48–51. https://doi.org/10.1145/3155128. ↵

- Lorini, Maria Rosa, Amalia Sabiescu, and Nemanja Memarovic, “Collective Digital Storytelling in Community-Based Co-Design Projects: An Emergent Approach,” The Journal of Community Informatics 13, no. 1 (2017): 109–36, https://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v13i1.3296. ↵

- McDowell, Kate and Nicole A. Cooke. “Social Justice Storytelling: A Pedagogical Imperative.” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 92, no. 4 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1086/721391 ↵

- Delgado, Richard and Jean Stefancic. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. New York University Press, 2023. ↵

- Ladson-Billings, Gloria. Critical Race Theory—What It Is Not! In Handbook of Critical Race Theory in Education (pp. 32–43). Routledge, 2021. ↵

- Solórzano, Daniel G., and Tara J. Yosso. “Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research.” Qualitative Inquiry, 8, no. 1 (2002), 23–44, https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040200800103. ↵

- Cooke, Nicole. “Becoming New Storytellers: Counterstorytelling in LIS.” In Information Services to Diverse Populations: Developing Culturally Competent Library Professionals, 113–36. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2017. ↵

- McDowell, Kate and Nicole A. Cooke. “Social Justice Storytelling: A Pedagogical Imperative.” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 92, no. 4 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1086/721391. ↵

- Cooke, Nicole. “Becoming New Storytellers: Counterstorytelling in LIS.” In Information Services to Diverse Populations: Developing Culturally Competent Library Professionals, 113–36. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2017. ↵

- pg. 157, King, Martin Luther. “Beyond Vietnam.” In: A Call to Conscience, edited by Carson, Clayborne and Kris Shepard. Grand Central Publishing, 2001. ↵

- Cooke, Nicole. “Becoming New Storytellers: Counterstorytelling in LIS.” In Information Services to Diverse Populations: Developing Culturally Competent Library Professionals, 113–36. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2017. ↵