Rainbow Unit: Networks Big and Small

4A: Recovering Community: Designing for Social Justice

Background Knowledge Probe

Design

As transitive verb:

- To create, fashion, execute, or construct according to plan

- To conceive and plan out in the mind

- To have as a purpose

- To devise for a specific function or end

As intransitive verb:

- To conceive or execute a plan

- To draw, lay out, or prepare a design

As noun:

-

- A particular purpose or intention held in view by an individual or group

- deliberate purposive planning

- A mental project or scheme in which means to an end are laid down

- A deliberate undercover project or scheme

- Designs plural: aggressive or evil intent — used with on or against

- A preliminary sketch or outline showing the main features of something to be executed

- An underlying scheme that governs functioning, developing, or unfolding

- A plan or protocol for carrying out or accomplishing something (such as a scientific experiment); also: the process of preparing this

- The arrangement of elements or details in a product or work of art

- A decorative pattern

- The creative art of executing aesthetic or functional designs

- After reading this definition, put everything aside and pause for several minutes to reflect back on your journey through A Person-Centered Guide to Demystifying Technology. Explore especially the ways you’ve done aspects of design, whether as noun or verb, during this journey.

- When you return, review the titles of each social and technical session within the Orange, Blue, and Rainbow Units. How does this compare to, and further shape, your initial reflections on your journey through this book?

- Now skim the “Introduction to the Book” and the Orange, Blue, and Rainbow Overviews. How do these further shape your initial reflections on your journey through this book?

- With these reflections in mind, take a few minutes to brainstorm and creatively document a vision or two you may have of a person-centered collective leadership design of a networked information system.

The Designer in Each of Us!

What if our discipline made the shift from a science approach (organizing our professional knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the world) towards a design approach (identifying problems and addressing them with human-centered solutions)?

Miguel A. Figueroa, Foreword to Design Thinking[2]

To conclude, there are two possible futures for libraries: one is a passive future, in which libraries sit back and let others design solutions to information problems. The second one, and the one I know I prefer, is the one that libraries design. Design thinking is so pervasive in librarianship that libraries and librarians already have the power to create unique, powerful, value-laden experiences and help individuals, communities, and even societies solve information problems. It’s time to embrace design as a fundamental component of librarianship in order to create a better future for all.

Rachel Ivy Clarke, Design Thinking[3]

As noted by Merriam-Webster, design is a word with a range of definitions. To begin, let’s consider this within a very broad framing: to make something, it first needs to be implicitly or explicitly designed. When we are trained within a profession to move from rote use of tools and techniques at our disposal in order to accomplish tasks, to instead expanding upon the tools and techniques to assure they work for different populations and contexts, we are being taught to design and make new things or to further innovate-in-use and remix existing things. We have moved from use to design. We all design personally and professionally to some extent or another. But only some of us are formally given the job description of designer. As we’ve journeyed through the Units of this textbook, we’ve been immersed within a deep hands-on social + technical dive into sociotechnical artifacts including electronics, software, and networks culminating with what is hopefully now a more holistic understanding of networked information systems. We’ve met, and made active use of, skillsets, frameworks, and standards employed by a wide range of information professionals in selecting, co-designing, appropriating, and innovating-in-use networked information systems. Throughout this deep dive, a central objective has been the development of a critical approach to sociotechnical artifacts and the advancement of community agency in appropriating technology to achieve individual and community development goals. Core is an intent to move away from information science professionals as passive recipients of networked information systems designed by others to address information problems, and instead build from our already existing professional “power to create unique, powerful, value-laden experiences and help individuals, communities, and even societies solve information problems.”[4] Information science professionals and our patrons each move from use to design and back as needed to effectively take on information problems. In Design Thinking, Rachel Ivy Clarke notes:

Supporting patrons has always been a key component of librarianship, which has prided itself on being a user-centered profession. Early American librarianship was rooted in service to library users with the goal of improving their lives through exposure to books, reading, and literacy. Reading was emphasized as a means of intellectual, moral, and social education and improvement. But this meant that the tools and services created by libraries for users were often based less on what users wanted to read and more on what librarians thought users should read; usually this meant classic, culturally uplifting texts in the Western literary canon. Although this agenda certainly had users at its center, today it is criticized for its cultural presumption and its imposition of certain values.[5]

Especially beginning in the mid-twentieth century, efforts have been made to move from assumptions to investigations of what is actually needed and wanted, such as through the use of “needs assessments.” This form of design has been heavily influenced through user-centered design (UCD) in which “design is based upon an explicit understanding of users, tasks, and environments; is driven and refined by user-centered evaluation; and addresses the whole user experience. The process involves users throughout the design and development process and it is iterative. And finally, the team includes multidisciplinary skills and perspectives.”[6]

However, as noted by Sasha Costanza-Chock in Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need, “Design always involves centering the desires and needs of some users over others. The choice of which users are at the center of any given UCD process is political, and it produces outcomes (designed interfaces, products, processes) that are better for some people than others (sometimes very much better, sometimes only marginally so). This is not in and of itself a problem. The problem is that, too often, this choice is not made explicit.”[7] Clarke adds, “User-centered approaches, by their very name, focus on use: things like completing a task or accomplishing a goal. The word user reduces people to the use of a thing, rather than engaging with their experiences as human beings.”[8]

While user-centered practices are works of design, user-centered design too easily results in the user being identified as an entity completing a task, ultimately a work of dehumanization. An alternate holistic approach incorporating empathetic techniques has emerged attempting to re-center human beings as individuals. “It’s a process that starts with the people you’re designing for and ends with new solutions that are tailor made to suit their needs. Human-centered design (HCD) is all about building a deep empathy with the people you’re designing for; generating tons of ideas; building a bunch of prototypes; sharing what you’ve made with the people you’re designing for; and eventually putting your innovative new solution out in the world.”[9] A central aspect of human-centered design is to consider not only the actions of design work, but the thought processes that underly these actions. Design thinking emerged as a term in the 1960s to describe this key aspect of design found across a wide range of design disciplines.

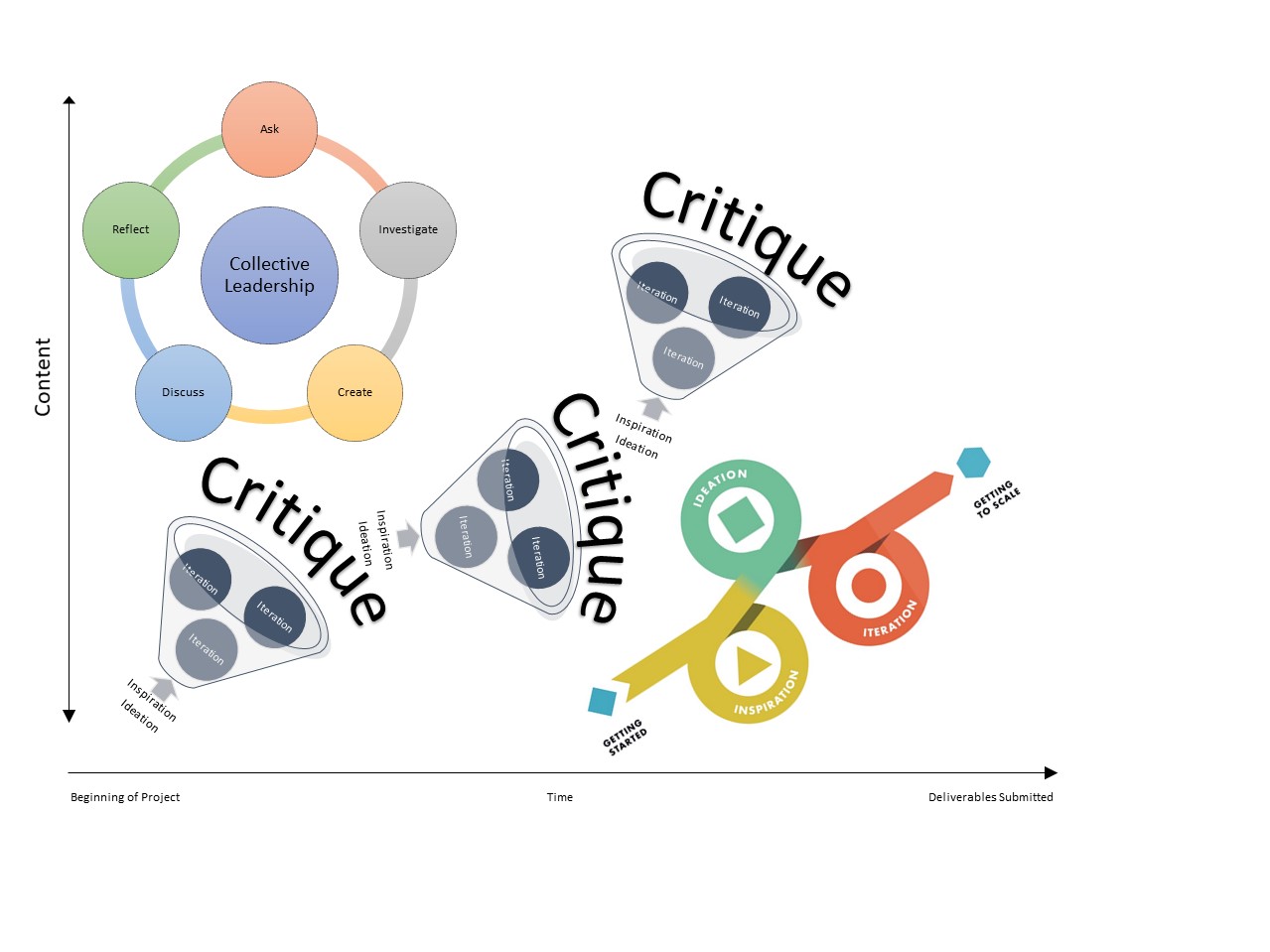

Indeed, consider our own work throughout the sessions and units of this textbook, and you’ll find ongoing cycles of action-reflection praxis — reading, watching, discussing + hands-on actions alone and within pairs/small groups + individual and corporate reflections. Together, these move us from use to design to broader thinking regarding design processes and the shapers of design and product. There is the risk that as with so many other concepts that reach popular use, design thinking is taken out of the more rigorous, extended work of design as a mental pat of congratulations for being thoughtful and empathetic while continuing a user-centered approach. And there is a risk that this design thinking is done in ways that shape design to conform to dominant narratives. But critically, strategically, and communally used, design thinking becomes a valuable mindset while working to resolve ill-defined problems using critical abductive reasoning within a broader design justice approach as we’ll explore in the next section.

In the 1990s, one of the lead faculty at the Stanford University Design School, David Kelley, also worked to bring design thinking into the field through the founding of IDEO, a global design and consultancy company. And through more recent funding by the Global Libraries program at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, IDEO led to the creation of a Design Thinking for Libraries toolkit in collaboration with Chicago Public Library in the United States and Aarhus Public Libraries in Denmark.

Libraries are a center for information access and serve to benefit their people in a wide range of ways. Over time, approaches and perspective have had to change to adapt to new opportunities and needs. But the challenges are real, complex, and varied within a rapidly evolving information landscape. Design thinking within the library context seeks to foster deeper understanding of the needs of patrons and to engage with communities in new ways. The design thinking processes listed in the toolkit bring forward a few formulas that might prove useful in moving from learning about the terms and concepts of digital technologies to considering ways these technologies can be further designed and remixed by the communities of practice of which you are a part or whom you are serving within a support and resource role. And as information scientists, the activity toolkit may also prove a useful base as we enter into collaborations with design professionals who bring to the collective leadership deeper formal training in design techniques, including form, composition, balance, typography, visual literacy, color theory, etc. In practice, it’s also helpful to include within the toolkit alternate terms to those within the “Design Thinking” framing, such as:

- Inspiration: Discovery, Interpretation, Empathize, Define

- Ideation: Ideate, Create, Prototype, Rapid Prototyping

- Iteration: Implementation, Experimentation, Deliverable, Test, Evolution

And consider, too, that this design thinking framework itself is another way of considering the ongoing inquiry cycle done in community, with community, and for community that includes: … → Ask → Investigate → Create → Discuss → Reflection → Ask → …

Design Justice

Library and information science is a profession dedicated to advancing the informed decision-making abilities of individuals, communities, and societies. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century:

Libraries played a significant role by portraying themselves as socially uplifting agents, developing library services to meet the needs of European immigrant populations during the foundation years (1900–1917), or during the era of depression and war (1930–1945), and afterwards, where the focus was on economic recovery and revitalization. During these times, the library provided liberating directions for social justice outcomes in nurturing just and fair ideals, expanding the base of impact to include outreach populations, creating a service-based ethics in the profession, and forging partnerships with community-based social justice agencies towards common goals.[10]

Bharat Mehra, Kevin S. Rioux, and Kendra S. Albright, “Social Justice in Library and Information Science”

As the twentieth century came to an end and we entered the twenty-first century, these works also included community networking, community technology centers, digital literacy training, and addressing the digital divide. “These included social justice activities and initiatives, even though the rhetoric and vocabulary of ‘social justice’ had not been significantly incorporated into the mainstream profession.”[11] Mehra, Rioux, and Albright acknowledge there is no universally accepted definition for social justice, and moreover, social justice theory specific to library and information science is still within its infancy:

Historically, social justice has been concerned with the tensions between: 1) the individual’s right to choose her/his own ends; 2) conflicts with other individuals’ rights to make similar choices; and 3) the debate on individual rights vs. the good of the community.[12]

The lessons from the past are today providing libraries directions to develop a new approach that recognizes:

- importance of outcome-based, socially relevant evaluation methods in assessing library services;

- value of local experiences and ontologies and their representation into formalized organizational tools of information; and

- necessity in building equitable partnering efforts with disenfranchised constituencies.[13]

Human-centered design has served as an important transition point from previous user-centered approaches to design in helping the information science profession move towards a person-centering of sociotechnical design, implementation, and use. This textbook builds from over 20 years of social justice-oriented teaching, research, and practice that has included extensive use of service projects, community inquiry, and engaged scholarship to bring together the school and community to advance community goals. But a 2008 ethnographic study of my course “Introduction to Networked Information Systems” conducted by Junghyun An found that without greater criticality, incorporation of human-centered design techniques and social justice-oriented pedagogies and goals into design studio service projects too easily left true action-reflection praxis at a superficial level.[14] An’s valuable study underlined important aspects, and highlighted key shortcomings, of my own ongoing research that has emphasized the essential need for critical ongoing thinking regarding the various social issues and problems within our own technology design and use practices, as well as those of others shaping these technologies. And of central importance is that these reflections include collaborative discussions within our own profession and related professions, and also very importantly with the wider range of stakeholders, especially those marginalized and oppressed via the shaping that is embedded within and emerges from these technologies.

This textbook was birthed through deep nights of the soul that especially emerged beginning in the late 2000s. Rather than learning-by-doing specifically as a service-learning action, it now seeks to be a learning-by-doing action-reflection praxis as a primer for true ongoing professional design justice works. The action-reflection learning-by-doing praxis of this textbook happens as we use our deepening understanding of the components and concepts underlying electronics, software, and networks to build a picture, or codification, of these artifacts within real situations and people, including those forgotten and marginalized. It happens as we then work to decodify the artifacts and associated codes by looking at certain aspects in order to build a new lens on the larger sociotechnical artifacts. It continues to happen as, through this work of action and reflection, we reach towards a recodification to move from magical thinking about networked information systems that are designed by others for our passive professional use to meet patron needs, and instead envision an alternate, social justice path for our profession that centers around community inquiry and collective leadership engaging all members of local communities.

But for this to happen, we need to assure our human-centered design thinking is centered within a design justice approach. Costanza-Chock argues that this work is:

…about the relationship between design and power. It’s about the growing community of designers, developers, technologists, scholars, educators, community organizers, and many others who are working to examine and transform design values, practices, narratives, sites, and pedagogies so that they don’t continue to reinforce interlocking systems of structural inequality. It’s about design, social justice, and the dynamics of domination and resistance at personal, community, and institutional levels. In essence, it’s a call for us to heed the growing critiques of the ways that design (of images, objects, software, algorithms, sociotechnical systems, the built environment, indeed, everything we make) too often contributes to the reproduction of systemic oppression. Most of all, it is an invitation to build a better world, a world where many worlds fit; linked worlds of collective liberation and ecological sustainability.[15]

Costanza-Chock works towards a recognition that development of new information and communication technologies (ICT) needs to “not only take shape in Silicon Valley, they also emerge from marginalized communities and social movements, both during waves of spectacular protest activity and also in everyday life,” in order to “advance the growing conversation about the pitfalls and possibilities of design as a tool for social transformation.”[16] The Design Justice Network and its underlying principles are central to Costanza-Chock’s vision. Considered part of a living document, these principles emerged over several years of work as part of the Allied Media Conference held in Detroit. As of a summer 2018 update, the Design Justice Network Principles are:

Design mediates so much of our realities and has tremendous impact on our lives, yet very few of us participate in design processes. In particular, the people who are most adversely affected by design decisions — about visual culture, new technologies, the planning of our communities, or the structure of our political and economic systems — tend to have the least influence on those decisions and how they are made.

Design justice rethinks design processes, centers people who are normally marginalized by design, and uses collaborative, creative practices to address the deepest challenges our communities face.

Principle 1: We use design to sustain, heal, and empower our communities, as well as to seek liberation from exploitative and oppressive systems.

Principle 2: We center the voices of those who are directly impacted by the outcomes of the design process.

Principle 3: We prioritize design’s impact on the community over the intentions of the designer.

Principle 4: We view change as emergent from an accountable, accessible, and collaborative process, rather than as a point at the end of a process.[17]

Principle 5: We see the role of the designer as a facilitator rather than an expert.

Principle 6: We believe that everyone is an expert based on their own lived experience, and that we all have unique and brilliant contributions to bring to a design process.

Principle 7: We share design knowledge and tools with our communities.

Principle 8: We work towards sustainable, community-led and -controlled outcomes.

Principle 9: We work towards non-exploitative solutions that reconnect us to the earth and to each other.

Principle 10: Before seeking new design solutions, we look for what is already working at the community level. We honor and uplift traditional, indigenous, and local knowledge and practices.

Design Justice Network, “Design Justice Network Principles”, emphasis from document[18]

Design justice re-centers the role of digital literacy training using what Virginia Eubanks calls popular technology. Introduced in her 2007 article “Popular technology: exploring inequality in the information economy” and expanded further in her books Digital Dead End (2011) and Automating Inequality (2017), Eubanks systematically investigates the ways high-tech tools and jobs continue and expand social inequalities within the United States. To move beyond this dominant narrative, Eubanks brings forward an alternative digital literacy agenda that “make[s] technology analysis and development both relevant and empowering to people who live in persistent poverty, by drawing on traditions of popular education in South America (articulated by Paulo Freire) and the United States (articulated by Myles Horton and the Highlander Research and Education Center).”[19] Eubanks underlines that as a digital literacy strategy, “popular technology reminds us that technology is not a destiny but a site of struggle.”[20] A popular technology approach:

- Resists oppression in the form of exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism, and violence;

- Draws on cognitive, cultural, and institutional difference as a resource; and

- Engages in participatory decision making in agenda setting, design, implementation, and evaluation.

In the Laura Flanders Show episode below, Eubanks further introduces Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor before describing the 2018 Allied Media Conference and the “Our Data Bodies” project, developed in collaboration with members of the Detroit Community Technology Project. These all serve as examples of coalition work and collaboration that should be the essential centering of all radically reconsidered digital literacy training, technology design, and sociotechnical artifact and system implementation. Eubanks highlights the Allied Media Conference as an “incredible space where we have difficult conversations about media, technology, and social justice. But the folks who are here are makers. They’re organizers, they’re activists, so they make spaces and they make movements. But they also make stuff.” She highlights the math-washing that leads us to believe things, issues, and solutions are more complicated than we can handle: “It’s true there might be a really technically complicated system that takes a little bit of breaking down for us to understand, but we understand the problems and we understand the solutions and we understand actually even some of the really complicated technologies that are out there once we have the language, the basic language to do it.” View this video to hear Eubanks’ story.

The Studio Space

Makerspaces, Tinkering Studios, Fab Labs, and other creative spaces have become increasingly commonplace as workspaces bringing people together to engage in conceiving, designing, and developing new artifacts. They often incorporate both traditional crafts and also emerging digitally based crafts. Beyond general action-reflection that includes various inspiration, ideation, iteration, and “act, investigate, create, discuss, reflect” cycles, a key component of effective design is the critique process. Clarke describes the critique in Design Thinking:

Critique is a rigorous form of evaluation that is central to the discipline of design. Critique may call to mind scary memories of harsh, negative criticism, perhaps in front of peers, like reading a poem aloud in a creative writing class only to have the instructor and classmates rip it to shreds. However, well-executed design critique is not subjective negativity. Critique is not about whether you “like” a design or approve of its aesthetics. A good critique says why something does or does not work for that individual. It asks questions and elicits the rationale for a design decision. A critique is about discovering what’s not working in order to make a design better. It can be a hard process to learn to take critique well, and even harder to learn to give a critique well. The critique of a design—especially one you are emotionally invested in—can feel like a personal blow. This is why it’s important to seek critique throughout the design process.[21]

Critique can take many different forms, and it is often helpful to make strategic use of selected forms at different points within the design process. The following is a list of some of these I’ve found helpful within my community informatics studios:

Table 2. The design critique as a model of distributed learning.[22]

| Critique Type | Brief Definition | Mapped to Traditional Academic Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Formal | Public, invited, summative, evaluation events | Structured and summative presentation formats: peer-reviewed journals, advanced degree oral defenses |

| Seminar/Group | Semipublic, less formal, more generative, but occasionally evaluative | Symposium format in which development of ideas or products is stressed as a group |

| Desk | Conducted with mentor or instructor, highly generative, modeling of cognitive behavior potential for incidental learning | Modeling for graduate students, professional participation, individualized instruction |

| Peer | Highly informal, generative, voluntary or on request | Structured, scaffolded critique; informal sharing or practice of work; 3-person critique |

Rooted in the apprentice model of learning in which students study with master craftspeople or artists to develop their craft, studio classes emphasize learning by doing, often through iterative, multimodal analysis, proposition building, design, making, and critique of different alternatives that might address community-based problems. It has been an integral pedagogy in practitioner-based fields such as architecture, urban planning, and fine and applied arts. Studio-based learning aligns closely with John Dewey’s concept of experiential learning. For instance, Dewey emphasized the importance of helping students shape their purpose for a given activity by constructing a plan based on their impulses, past experiences, and community knowledge to maximally shape the current learning environment. In this way, teachers act more like “guides” to assist students in developing and implementing their design and making choices. Students and instructors work together within a studio space that serves as a model of professional practice. Regular written reflections also help students think more deeply about the paths that lead them to their final project processes, outputs, and outcomes.

Much of the service-learning coursework that has guided the creation of this textbook emerged originally through my work as part of the East St. Louis Action Research Project (ESLARP), one of the oldest community-university partnership programs in the United States. The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign was pushed to engage with the East St. Louis community, situated 175 miles away, when in 1987 State Representative Wyvetter Younge aggressively worked to bring the University into this most devastated city in the state, in order to provide essential assistance through participatory action research (PAR) projects in community, with community, doing collective inquiry and experimentation grounded in lived experiences and social histories. Later, Recreation Sports and Tourism, Library and Information Science, and Law joined the collaboration.[23] It was here that I first began unwittingly making use of studio techniques for analysis, proposition building, design, making, and critique as I watched the works of other university instructors. I also later began a series of community-university collaborations to develop and introduce to the LIS profession a formal Community Informatics Studio course that centralizes place-making and popular technology workshops, within which sociotechnical artifact design and implementation serves a valuable supporting role.[24][25] This aligns strongly with the person-centered, hands-on guide for working with information and communications technologies as covered in this textbook, and provides a potential tool for establishing and further advancing design justice as a part of our ongoing community inquiry activities in daily professional field practices.

Whether in the Makerspace or Tinker Studio, as part of design justice projects and networks, or in a community center meeting room, you have knowingly or unknowingly joined into a studio which includes various aspects of design and making. While some will have had formal training as designers, all of us bring in our lived experiences doing design practices. These movements are working to break down barriers to full participation in the analog and digital realms of sociotechnical artifacts, and to advance empowerment for all. But as Angela Calabrese Barton and Edna Tan note in STEM-Rich Maker Learning: Designing for Equity with Youth of Color:

At the same time, it is important to ask questions about how the movement defines who makers are, what makers do, and what kinds of access makers need to tools and opportunities to keep making. These questions cannot be divorced from considering the social, racial, gendered, economic, and political conditions in which particular makers are bound. Espousing an egalitarian vision of making may symbolically level the playing field, while the reality is that access and opportunities to make for some groups of the population continue to remain sporadic.[26]

Barton and Tan further note: “It is always rooted in the history and geographies of young people’s lives and in the broader context of making and makerspaces in the United States and beyond.”[27] Problem identification and analysis, design, and making practices and expertise build through iterative and incremental works. But what types of practices and expertise are built? How does this go on to impact the longer-term shaping of people, communities, and societies? For us to move from social justice intent to truer forms of social justice practices, it is essential for the information science profession to continue our progression implementing design justice principles and practices.

This chapter serves as a brief general introduction to design thinking, design principles, and design processes, and the ways that these need to center around design justice as one aspect of addressing real-world problems with community-based and -led social justice action and reflection praxis. To do this, Costanza-Chock notes that “design justice builds on, but also differs in important ways from, related approaches such as value-sensitive design, universal design, and inclusive design.”[28] Others, too, are finding it important to bring together a breadth of design approaches while also considering ways in which designing for values will need to differ from certain approaches given current contexts.

Located in The Netherlands, Delft Design for Values Institute brings together a diversity of design approaches, theoretical backgrounds, considered values, and application domains within the design field more broadly. Internal and external value dynamics across the broad spectrum of stakeholders need to be grasped and connected to achieve a more inclusive and successful design.

Pieter Vermaas et al. note how “increased attention in design for values of users and of society at large has found its way also to design methodology.”[29] Modern design methods have moved from a previous focus on functionalities, affordances, and disaffordances, to contemporary methods that use methodologies such as ethnographic research to clarify the values at play in the problems of users, for instance regarding conflicting values of safety and privacy. To this end, a common design method bringing together user perspectives and user-driven design is participatory design.

But as the scale of design outcomes expands, it is sometimes necessary to move beyond user-driven user perspective change, to broader user-driven social perspective change using transformation design methods to broaden the distribution of power within the decision-making process and bring forward a broader social perspective, as may be the case in the design of backbone Internet services used to connect multiple First Nations first-mile local area networks. As the complexity continues to increase, it becomes ever more challenging for design to be directly user-driven, and therefore design for values sometimes uses larger-scale, designer-driven social implication design methods. Still, even as complexity increases, as Fischer and Herrmann note in “Meta-Design: Transforming and Enriching the Design and Use of Socio-Technical Systems,” a meta-design framing can be used to design for design after design, facilitating user-as-designer, or what Bruce et al. call innovation-in-use, at the use time of a product.[30][31]

Community technology design, as with many other areas of design, requires the bringing together of many different fields of research and practice that also include human-computer interaction (HCI), design studies, computer science, community studies, and community informatics. This is not something the information sciences profession can do in a silo. For all involved, concerns continue to grow regarding the cultural black box in community technology design, expanding on the existing range of social shaping of technology concerns that have been raised throughout this textbook.[32] It is for this reason that design justice might provide an essential central gathering point if we are to rapidly transition from a “thing-oriented” society to a “person-centered” society.

Lesson Plan

In the last chapter, you were introduced to a famous quote by the late John Lewis, an American civil rights icon who was part of the 1961 Freedom Rides, served as the first chairperson of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and was a leader with the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., of the march on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, in 1965, that was violently halted by police and later became known as “Bloody Sunday.” John Lewis went on to direct the Voter Education Project before being appointed by then-President Carter to lead ACTION, the umbrella federal volunteer agency that included the Peace Corps and Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA). In the 1980s, Lewis became a politician in the Atlanta city council, and then served as a representative in the U.S. Congress. For Lewis, each of these were part of his larger philosophy of a life well lived.

My philosophy is very simple: When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have to stand up, you have to say something, you have to do something.

My mother told me over and over again when I went off to school not to get into trouble but I told her that I got into a good trouble, necessary trouble. Even today I tell people, “We need to get in good trouble.”

John Lewis, interviewed by Valerie Jackson for StoryCorps[33]

Getting into “good trouble” can take many forms throughout one’s life as we participate in ongoing inquiry cycles of asking the better question, investigating possibilities, doing creative acts to address limit situations, taking part in community discussions, and doing ongoing works of reflection. These are the works of recovering community through design for justice.

This session especially focuses on design frameworks and approaches that 1) recognize the designer in each of us, and 2) the essential need for an integration and practice of design to advance the recovery of community. As with all aspects of popular education, these cycles do not bring us to an end point, but rather bring us to new starting points as we continue true social justice works. It is for this reason that popular technology training and design-justice-related processes cannot be done exclusively, or sometimes even primarily, within formal education and professional practices. But where and how this should be done is not something that can be taught. It is something that needs to be discovered in community, with community, and for community. Core to the lesson plan for this session, then, is a goal of opening up possibility for you to discover individually and, to the extent possible within your communities, what introductory development of design frameworks and processes you specifically still need.

Essential Resources:

This article is a 2014 Keynote given at the Illinois State University Critical Media Literacy Conference, and was written by five University of Illinois students who tested the feasibility of several of the key aspects of the De-mystifying Technology workshop framework that is now represented in this book. This feasibility was tested as part of a participatory action research process in community and with community that included design as one part of a Community Informatics Studio course, and gives a valuable example of the critical design process in action within its broader community inquiry context.

- Stangl, Angela; Haniya, Samaa; Naples, Kim; McCoy, Casey; and Ransberger, Rebecca, “Promoting Digital Literacy: The De-mystifying Technology Workshop for Families” (2020). Critical Media Literacy Conference. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/criticalmedialiteracy/2014/Keynote/2

The following case studies and toolkits should be seen as some possible pathways from which you could choose in support of your own lesson plan. Some of these have a specific design focus, while others are community-centered activities in which design justice principles and practices have played a role.

- Lorini, Maria Rosa, Amalia Sabiescu, and Nemanja Memarovic. “Collective Digital Storytelling in Community-Based Co-Design Projects: An Emergent Approach.” The Journal of Community Informatics 13, no. 1 (2017): 109–36. https://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v13i1.3296. This resource from the Orange Unit is a case study not just of digital storytelling, but also more broadly within co-design projects.

- Strohmayer, Angelika, and Janis Meissner. “‘We Had Tough Times, but We’ve Sort of Sewn Our Way through It’: The Partnership Quilt.” XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students 24, no. 2 (December 19, 2017): 48–51. https://doi.org/10.1145/3155128. Also from the Orange Unit, this case study especially highlights a feminist framework for human-centered computing and HCI.

- Cumbula, Salomao David, Amalia Sabiescu, and Lorenzo Cantoni. “Community Design: A Collaborative Approach for Social Integration.” The Journal of Community Informatics 13, no. 1 (March 22, 2017). https://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v13i1.3299. This case study highlights a successful co-design and implementation of a community multimedia center, and notes ways that broader-scale research and development projects can be done in ways that also specifically bring local stakeholders into the design process.

- FirstMile. “Community Stories,” 2016. http://firstmile.ca/community-stories-2/ and FirstMile. “Free Online Course: Colonialism and the e-Community,” 2016. http://firstmile.ca/free-online-course/. The First Mile consortium of First Nations have worked since 2005 to bring Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) to remote and rural First Nations using a critical lens. As noted in the parent webpage, these “stories outline innovative, industry-leading uses of ICTs and broadband by First Nations communities and organizations in areas including art, education, and health.” The free online course on Indigenous peoples and the e-Community is a living resource that provides essential background information for all seeking to reframe ICT within this critical lens.

- de Moor, Aldo. “Citizen Sensing Communities: From Individual Empowerment to Collective Impact,” In Proceedings of the 17th CIRN Conference, November 6-8, 2019, 91–101. Monash Centre, Prato, Italy. https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/2219800/CIRN2019-complete.pdf and de Moor, Aldo. “Increasing the Collective Impact of Climate Action with Participatory Community Network Mapping.” Livingmaps Review no. 8 (April 29, 2020). http://livingmaps.review/journal/index.php/LMR/article/view/197. These two articles provide case studies highlighting how a research consultancy firm can serve an essential role in building collaborative common ground between stakeholders in an organization, network, or community.

- Commotion Wireless. “Where It’s Used.” Accessed July 22, 2020. https://commotionwireless.net/about/where-its-used/ and Commotion Wireless. “Commotion Construction Kit – Planning.” Accessed July 22, 2020. https://commotionwireless.net/docs/cck/planning/. These case studies and design activity are part of a larger toolkit of free, open-source communication technologies and design processes leading to establishment of community wireless mesh networks.

- M-Lab. “What Is Measurement Lab?” Accessed July 22, 2020. https://www.measurementlab.net/about/ and M-Lab. “Papers, Presentations, and Regulator Filings,” Accessed July 22, 2020. https://www.measurementlab.net/publications/.M-Lab. “Internet Measurement Tests.” Accessed July 22, 2020. https://www.measurementlab.net/tests/. These tools and publications are not specific to design processes, but rather provide an essential toolkit for information collection as part of the information search process. Its use has included work within public library settings. This information can then be incorporated into data storytelling that both helps within a collective leadership design process and also within the structuring of community group critiques.

Professional Journal Reflections:

- Return now to the reflections, brainstorming, and vision documentation of the Background Knowledge Probe at the start of this session. What has remained constant and what has transformed within those as you’ve reviewed the session materials and entered into a critique?

- Review your reflections from session three of the Rainbow Unit. Is there anything you would further revise as you explored past reflections within the context of session three and now session four?

- What are some additional thoughts regarding next steps you need to take individually and within your communities of practice in response to your journey through A Person-Centered Guide to Demystifying Technology?

- Merriam-Webster, “Design,” accessed July 3, 2020, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/design. ↵

- Figueroa, Miguel A. Foreword to Design Thinking by Rachel Ivy Clarke. (Chicago: ALA Neal-Schuman, 2020), vii. ↵

- Rachel Ivy Clarke, Design Thinking, Library Futures 4 (Chicago: ALA Neal-Schuman, 2020), 54. ↵

- Clarke, Design Thinking, 54. ↵

- Clarke, Design Thinking, 22-23. ↵

- “User-Centered Design Basics | Usability.Gov,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, April 3, 2017. https://www.usability.gov/what-and-why/user-centered-design.html. ↵

- Costanza-Chock, Sasha. Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need, Information Policy (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020), 77. https://designjustice.mitpress.mit.edu/. ↵

- Clarke, Design Thinking, 23-24. ↵

- Design Kit, “What is Human-Centered Design?”, accessed July 17, 2020. https://www.designkit.org/human-centered-design.html. ↵

- Mehra, Bharat, Kevin S. Rioux, and Kendra S. Albright, “Social Justice in Library and Information Science,” in Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences (CRC Press, 2009), 4823. https://doi.org/10.1081/E-ELIS3-120044526. ↵

- Mehra, Rioux, and Albright, “Social Justice in Library and Information Science,” 4823. ↵

- Mehra, Rioux, and Albright, “Social Justice in Library and Information Science,” 4820. ↵

- Mehra, Rioux, and Albright, “Social Justice in Library and Information Science,” 4824. ↵

- An, Junghyun. “Service Learning in Postsecondary Technology Education: Educational Promises and Challenges in Student Values Development,” University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2008. https://hdl.handle.net/2142/17387. ↵

- Costanza-Chock, Design Justice, preface, https://designjustice.mitpress.mit.edu/. ↵

- Costanza-Chock, Design Justice, preface, https://designjustice.mitpress.mit.edu/. ↵

- This principle was inspired by and adapted from the Allied Media Network Principles. ↵

- Design Justice Network, “Design Justice Network Principles,” accessed July 17, 2020. https://designjustice.org/read-the-principles. ↵

- Eubanks, Virginia. “Popular Technology: Exploring Inequality in the Information Economy.” Science and Public Policy 34, no. 2 (March 1, 2007): 131. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234207X193592. ↵

- Eubanks, Virginia. Digital Dead End: Fighting for Social Justice in the Information Age (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2011), 155. ↵

- Clarke, Design Thinking, 44. ↵

- Adapted from “Application of critique elements in academic practice and instructional design” © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2012. From: Brad Hokanson, “The Design Critique as a Model for Distributed Learning,” in The Next Generation of Distance Education: Unconstrained Learning, eds. Leslie Moller and Jason B. Huett (Boston, MA: Springer US, 2012), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-1785-9_5. ↵

- A very insightful reflection on this history of ESLARP can be found here: Sorensen, Janni and Laura Lawson, “Evolution in Partnership: Lessons from the East St Louis Action Research Project,” Action Research 10, no. 2 (June 2012): 150–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750311424944. ↵

- Wolske, Martin, Deven Gibbs, Adam Kehoe, Vera Jones, and Sharon Irish, “Outcome of Applying Evidence-Based Design to Public Computing Centers: A Preliminary Study,” The Journal of Community Informatics 9, no. 1 (November 25, 2012). https://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v9i1.3188. ↵

- Wolske, Martin, Colin Rhinesmith, and Beth Kumar, “Community Informatics Studio: Designing Experiential Learning to Support Teaching, Research, and Practice,” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science 55, no. 2 (April 2014): 166–77. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/48952. ↵

- Barton, Angela Calabrese and Edna Tan, STEM-Rich Maker Learning: Designing for Equity with Youth of Color (New York: Teachers College Press, 2018), 1-2. ↵

- Barton and Tan, STEM-Rich Maker Learning, 107. ↵

- Costanza-Chock, Design Justice, 46. ↵

- Vermaas, Pieter E., Paul Hekkert, Noëmi Manders-Huits, and Nynke Tromp, “Design Methods in Design for Values,” in Handbook of Ethics, Values, and Technological Design: Sources, Theory, Values and Application Domains, eds. Jeroen van den Hoven, Pieter E. Vermaas, and Ibo van de Poel (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2015), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6970-0_10. ↵

- Fischer, Gerhard and Thomas Herrmann, “Socio-Technical Systems: A Meta-Design Perspective,” International Journal for Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development 3, no. 1 (2011): 1–33. https://doi.org/10.4018/jskd.2011010101. Also available at https://l3d.colorado.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Published-JOURNAL-version.pdf. ↵

- Bruce, Bertram C., Andee Rubin, and Junghyun An, “Situated Evaluation of Socio-Technical Systems,” in Handbook of Research on Socio-Technical Design and Social Networking Systems, eds. Brian Whitworth and Aldo de Moor, 2:685–98. Information Science Reference (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 2009. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-264-0.ch045. ↵

- For more on this idea, see: Sabiescu, Amalia, Aldo de Moor, and Nemanja Memarovic, “Opening up the Culture Black Box in Community Technology Design,” AI & Society 34, no. 3 (September 1, 2019): 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-019-00904-z. ↵

- Lewis, John and Valerie Jackson, “The Boy From Troy: How Dr. King Inspired a Young John Lewis,” StoryCorps, February 20, 2018. https://storycorps.org/stories/the-boy-from-troy-how-dr-king-inspired-a-young-john-lewis/. ↵