4 Active Learning: Engaging People in the Learning Process

Introduction

Active learning, as the name implies, is any type of learning that involves direct interaction with the content or materials. Active learning has seen increasing popularity over the past few decades, beginning in 1984 with a report from the National Institute of Education which identified student involvement in learning as a condition of success in education. The report promoted active learning as a way to encourage more student involvement and called on faculty to “make greater use of active modes of teaching and require that students take greater responsibility for their learning” (p. 38). Likewise, in 1987, Chickering and Gamson listed active learning as one of the seven principles to improve undergraduate education. In recent decades, proponents have recommended the integration of active learning techniques in virtually any learning environment and with all age groups, from preschool through higher education, as well as continuing education and professional development. This chapter begins with an overview of active learning, including arguments for implementing it throughout learning experiences, as well as some of the concerns or challenges to integrating the techniques into the classroom. The chapter concludes with examples of some common active learning approaches and techniques.

What Is Active Learning?

Active learning involves direct engagement with course material, such as discussion, debate, role playing, and hands-on practice. In contrast, passive learning does not directly involve the student; examples of passive learning include lecture or demonstration, where students listen and watch but do not actively participate. Bonwell and Eison (1991, p. iii) define active learning as “instructional activities involving students in doing things and thinking about what they are doing.” In other words, active learning includes direct interaction with content but also has a metacognitive element that promotes reflection on learning. While we can use active learning approaches with individual learners, many of the techniques emphasize group work and collaboration. In addition to classroom activities, active learning can take place outside the classroom through experiences like internships, service-learning opportunities, and assignments that involve interaction and reflection. However, this chapter will focus on instructor-designed active learning that takes place in venues such as classrooms, workshops, and webinars, as these are the experiences with which information professionals will most likely be involved.

Active learning has its roots in several of the theories described in Chapter 3. Humanists reject the notion that learners are blank slates that passively receive information transmitted from teachers. Constructivists believe that learners construct knowledge, which presupposes active engagement with information in order to create new meanings and understandings, while social constructivists emphasize the importance of interactions with other people in constructing knowledge. According to cognitive scientists, learners actively engage with material as they retrieve information from long-term memory and make connections between new information and existing knowledge.

Active learning approaches challenge the traditional, or “banking,” model of education, in which learners are generally passive; they are expected to listen and take notes, but they are not required to interact with or think deeply about the content. At most, students are asked to recall and repeat what they have learned in an exam or paper. Active learning centers on the learner and encourages interaction, engagement, and reflection. The emphasis with active learning is less on content and more on skills and concepts, or learning how to learn (Thomas, 2009). This does not mean that active learning does not involve content, but more time is typically devoted to solving problems, analyzing issues, and reflecting on learning than, say, learning rote facts.

Despite the history and current popularity of active learning, the concept remains somewhat elusive. There is no unified theory or single set of practices for active learning. In a sense, active learning is an umbrella term that encompasses a range of approaches to teaching and learning and a wide variety of specific techniques. Prince (2004) identifies three of the most common approaches to active learning as collaborative learning, cooperative learning, and problem-based learning, each of which has different applications and implementations. Collaborative learning, according to Prince, is any type of learning in which students work together on a project or toward the same learning outcome. Cooperative learning is also collaborative, but the emphasis is on joint incentives and common goals, whereas collaborative learning is sometimes centered on competition. In problem-based learning, the instructor presents students with a challenge or scenario, often drawn from the real world, and students must develop solutions to the problem. Problem-based learning is often self-directed, with the instructor acting as a guide and facilitator rather than an expert with answers. Cattaneo (2017) classifies active learning activities as problem-based learning, discovery-based learning, inquiry-based learning, project-based learning, and case-based learning. She finds that each of these approaches is student-centered, but they vary quite widely in their implementation.

Finally, Graffam (2007) suggests that active learning has three components: intentional engagement, purposeful observation, and critical reflection. Intentional engagement is hands-on practice, where students perform the tasks or engage the skills they are expected to learn. For instance, LIS students might role play a reference interview, or a library instructor might have a group of undergraduates evaluate a website. In purposeful observation, students watch demonstrations or observe interactions in order to learn skills, tasks, or procedures. Demonstrations are quite common in library instruction, as when library instructors walk students through Boolean searching. Another example is having LIS students watch a reference interview in order to learn techniques for clarifying questions. The difference between demonstration and purposeful observation is that purposeful observation shifts the focus from the instructor, or demonstrator, to the learner, putting responsibility on the learner to pay attention and glean important information. Instructors can facilitate the process by describing each step in a demonstration and debriefing or asking questions after a simulation to draw attention to the important aspects. Finally, critical reflection is a metacognitive act in which students reflect on their learning. This step is crucial because it encourages students to make connections and helps to deepen the learning.

Ultimately, we can think of active learning as a set of best practices based on these broad, student-centered approaches. We can implement active learning in both face to face and online classrooms using specific methods and techniques such as discussions, think-pair-share, role playing, case studies, and jigsaws, as described in more detail later in this chapter. Activity 4.1 is a reflective exercise on active learning.

Activity 4.1: Active Learning: What Has Been Your Experience?

Think back on some of the learning experiences you have had in the past one or two semesters. These might include lectures, discussions, debates, writing exercises, videos, readings, demonstrations, role plays, and presentations, and they might have taken place in face to face or online courses, workshops, and conferences.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion:

- Would you characterize these various activities as active or passive?

- Did you find one type of experience more engaging?

- Did you feel as if you learned more with one type of experience than the other?

- Do you prefer one type of learning experience over the other? If so, why?

- Think about the different learning settings you’ve experienced: elementary school, high school, undergraduate, graduate, study abroad, professional development, workshops, online, face to face, and so on. Do you find that some of these experiences use active learning more than others? Why might that be?

- Could you imagine ways of incorporating active learning into some of the more passive experiences you have had?

The Case for Active Learning

Support for active learning abounds, but does this approach really work to engage students and increase learning? Bonwell and Eison (1991) state that students prefer active learning and that students in active learning classrooms are more engaged and motivated than those who are required only to passively listen to a lecture. They also maintain that active learning can promote higher-order thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation, while still achieving the same mastery of content as lectures. Overall, their claims seem to be supported. Prince (2004) found that collaborative and cooperative learning improved academic performance and led to better learning outcomes. Hake (1998) similarly found that active learning led to better test scores and increased problem-solving abilities, while Harris and Bacon (2019) indicate that active learning produces results at least as good as traditional, passive learning, and that it promotes both lower-order and higher-order critical thinking skills. Similarly, Freeman et al. (2014) found active learning to be beneficial, leading to improved exam scores. In fact, they went so far as to say that “if the experiments analyzed here had been conducted as randomized controlled trials of medical interventions, they may have been stopped for benefit—meaning that enrolling patients in the control condition might be discontinued because the treatment being tested was clearly more beneficial” (Freeman et al., 2014, p. 8413). The majority of studies on active learning have looked at children and young adults, but Uemura et al. (2018) found that active learning increased health literacy in older adults.

The benefits of active learning techniques do not seem to be limited to improved learning outcomes. For example, students in active learning classrooms tend to report more positive attitudes (Freeman et al., 2014), and there is some evidence that active learning reduces student attrition, meaning students are less likely to drop out of courses that utilize active learning techniques (Freeman et al., 2014: Prince, 2004). Prince (2004) also found evidence that cooperative learning improved students’ interpersonal skills and teamwork. Importantly, some evidence suggests that active learning might be more inclusive and benefit traditionally underrepresented and marginalized students in particular (Berry, 1991; Frederickson, 1998; Lorenzo et al., 2006; Rainey et al., 2019).

While the evidence for active learning seems positive, both Prince (2004) and Bernstein (2018) note that it is challenging to truly assess its impact because of the wide variety of approaches and techniques involved. Many studies assess only one small aspect of active learning or the implementation of a specific technique, and such studies are usually small and lack controlled variables, making comparisons across studies or generalizations of findings difficult. Bernstein (2018) suggests that rather than asking whether active learning works, instructors should consider which techniques work best under which circumstances. He finds that active learning needs to be highly structured and is most effective when students are required to engage, and suggests that instructors new to active learning take an incremental approach to integrating the techniques. In general, however, research suggests that in the best case, active learning leads to better performance, and at the very least, the performance of students in active learning classrooms is equivalent to their peers in more traditional contexts (Thomas, 2009).

Concerns and Challenges

Despite the popularity of active learning in the literature, and evidence of its effectiveness, lecture still seems to be the dominant form of instruction, especially in higher education. One reason for this might be familiarity. Most instructors teaching today learned through lecture, and it is natural for them to replicate what they know, especially if they have never been introduced to theories and pedagogies that promote other forms of learning. Bonwell and Eison (1991) identified a number of other barriers to adoption of active learning techniques. They note that change involves risk and can lead to uncertainty or anxiousness. New techniques rarely succeed perfectly on the first try, and instructors may have little incentive to innovate or try new teaching techniques, especially if they believe that their current approach is effective. Further, the lecture is familiar not just to instructors but also to students. Each is familiar with the role they are expected to play in a lecture-based classroom, making it comfortable, if not necessarily engaging.

Other common barriers to active learning include (Bonwell & Eison, 1991, p.59):

- Pressure to cover content

- Class sizes that are not conducive to active learning

- Time and planning involved in active learning

- Lack of materials or equipment

Instructors often feel that they have more material to cover than time in which to cover it. While this feeling is common across fields and grade levels, it is perhaps especially true of elementary and high school teachers, as well as college faculty in licensed fields such as nursing, all of whom need to teach specific content to prepare students to pass standardized exams. Lectures are a very efficient way of transmitting content. Active learning techniques, which require learner participation and often build in time for reflection, take up class time and leave less time to cover content. Librarians are not immune to this concern. In fact, because librarians generally have less time with students than a regular classroom teacher does, they might feel even more pressure to cram as much material as they can into the limited time that they have, resulting in sessions that are overpacked and rushed, as well as lacking in meaningful learning activities.

Active learning requires a shift in thinking as well as in techniques. The emphasis in active learning is on skills and competencies rather than on content. Through the various activities, students develop problem-solving, critical thinking, and reflection skills. In addition to learning specific content, students are putting skills into practice and learning how to learn. With that in mind, instructors may need to reduce the amount of material covered in class in order to make time for such skill building. However, this approach does not mean that the content is not covered at all. Rather, it might be delivered in different ways, often outside of regular classroom time. For instance, in a traditional classroom, instructors deliver content through lecture and demonstration, and then give students homework such as worksheets or other assignments where they practice or apply what they learned in class. However, instructors could have students read texts and watch videos outside of class that cover the same content the instructor might normally have delivered through an in-class lecture, then use class time for practice problems and skill building. This approach, sometimes referred to as the “flipped classroom,” is covered in more detail in Chapter 10.

Some instructors, especially at the college level, will find themselves in large classes of 100 or more students. Though such class sizes are less conducive to active learning than smaller classes are, it is not impossible to integrate some active learning even with hundreds of students (Harrington & Zakrajsek, 2017). One technique is a lecture pause, in which instructors stop the lecture and ask students to write down everything they remember from the lecture up to that point (or the two or three most important things they remember). The activity could end there, or the instructor could have students pair up to compare answers and perhaps fill in gaps in each other’s notes. This simple activity engages the students and entails the kind of retrieval practice that increases memory and retention of information.

Instructors can also be hesitant to try active learning because of the time involved or their own anxiety about trying a new activity. However, integrating active learning does not have to entail changing an entire workshop, session, or course; instructors can integrate active learning activities slowly over time. New activities will rarely work perfectly the first time through, so it makes sense to integrate a single activity, assess it, and make adjustments as necessary before adding more activities. Some experienced teachers might be able to add activities spontaneously. For instance, a confident and seasoned instructor might feel comfortable leading an unplanned discussion about a recent news story. But most instructors, especially those new to active learning, will find that each activity will take some time to plan ahead of its implementation. Ultimately, however, planning active learning activities is no more time-consuming than planning a detailed lecture.

Similarly, active learning does not have to depend on expensive materials and equipment. Technology can certainly enhance active learning, and many tools exist to increase student engagement. For example, many elearning platforms include online discussion boards, polling tools, document sharing, and even conferencing tools. However, many activities can be undertaken with few or no materials, such as the lecture pause described earlier that requires only a paper and pencil.

In addition to these four barriers, some teachers question the premise of active learning itself (Graffam, 2007; Thomas, 2009). Generally, these instructors are deeply rooted in traditional modes of teaching and understand instruction as the transmission of knowledge. This perspective can pose special challenges for academic and some school librarians, who are often guests in other teachers’ classrooms. If a librarian is invited to speak in the class of an instructor who does not view active learning as “real” teaching, the librarian might be hesitant to incorporate such techniques even if they support them. On the other hand, the librarian could view this as an opportunity to model good instructional practice. One or two judiciously chosen activities that engage students could demonstrate the effectiveness of active learning, and the librarian could enhance the technique by being transparent in their instruction. By explaining why they incorporated a particular activity, identifying its learning outcomes and the ways in which the activity achieves those outcomes, and by having students reflect on their learning, the librarian can help both the student and a reluctant instructor see how the techniques work.

Finally, students can also be resistant to active learning (Bonwell & Eison, 1991; Thomas, 2009). After all, active learning requires learners to engage and participate, and puts more responsibility on them. Students who are used to listening to lectures and taking notes might be confused or put off by active learning activities, at least at first. In fact, some students believe they learn less in active learning classrooms than they do from lectures, even though the research suggests the opposite (Miller, 2019). Just as engaging in active learning entails some risk for the instructor, it also can feel risky to the learner. Active learning often requires students to share thoughts, ideas, and answers in small and large groups, and some learners might be nervous about giving a “wrong” answer or sharing an unpopular idea. Further, the interaction with peers might be stressful for some people, especially shy, introverted, and neurodiverse students for whom social interaction can be anxiety-inducing (Cohen et al., 2019; Cooper et al., 2018; Monahan, 2017).

Certain active learning techniques, such as cold-calling, or randomly calling on a student who has not volunteered to answer a question, are particularly likely to be stressful for learners (Cooper et al., 2018). Most other techniques, however, can be implemented so as not to cause such anxiety. For instance, low-stakes activities that have little impact on a students’ grade reduce the potential for anxiety. Learners also tend to feel more comfortable when they are familiar with an activity (Bonwell & Eison, 1991), so introducing an activity by explaining its purpose, how it will be implemented, and what the expectations of students are can help ease fears. Bonwell and Eison (1991, p. 69) classify a range of instructional learning techniques according to the amount of risk they present to students. Activities that involve less speaking or presenting, such as lecture pauses, self-assessment activities, and structured small group discussions, are lower risk and lower stress. Higher risk, higher stress activities like role playing and presentations are more often group- or whole-class-based and require more speaking or interaction.

Developing trust between the instructor and students and among the students themselves can be crucial to successful active learning, especially when the activities will require students to interact with one another. Many of the techniques already mentioned, such as being clear about expectations and using low-stakes activities, can help build trust. We can also work with learners to establish ground rules for interactions—for example, encouraging active listening and respect during discussions. It can be helpful to give students time to get to know each other before assigning group work, and allowing students to choose their own groups so that they can find peers with whom they are comfortable (Cohen et al., 2019). Having people work in pairs rather than larger groups might also be less intimidating for some. Finally, simply allowing learners time to gather their thoughts before expecting them to join a discussion can be helpful. For instance, after asking a question of the class, try waiting a few extra seconds before choosing a volunteer, or give students time to reflect and jot down their thoughts before launching a discussion. Activity 4.2 addresses strategies to overcome faculty and student resistance to active learning.

Activity 4.2: Engaging Students in Active Learning

Read through the brief scenarios below and answer the questions that follow:

Scenario 1: Lisa is a user services librarian in a public library. She leads a popular series of job hunting workshops and has always had positive reviews. In the past, Lisa would mostly lecture, but recently she decided to incorporate some active learning. During one session, she had patrons pair off to practice answering interview questions and giving each other feedback on the answers. After the workshop, a patron complained that she had come to the workshop to learn from Lisa, not from other students who did not know any more than she did. She felt that Lisa was not “teaching” them how to do a good job interview.

- Why might the patron feel this way?

- Why might Lisa believe this is a good activity for this workshop?

- What might Lisa do or say to persuade this patron that such peer interaction and role playing is a legitimate teaching and learning activity?

Scenario 2: Ben is a school librarian who believes in the value of active learning and peer-to-peer instruction. During class, he always asks students to come to the front of the room to demonstrate different skills and tasks like keyword and subject searching, rather than leading the demonstration himself. He likes the fact that the peers show each other how to do these tasks by explaining what they are doing and why they are doing it, and he can act as a coach, guiding and correcting them as needed. However, Ben has noticed that when he asks for volunteers, only a few students raise their hands, and it is usually the same students who volunteer every time.

- Why might some learners be hesitant to volunteer in Ben’s class?

- Even if more students volunteer, Ben probably has time to let only two or three students demonstrate in each class. Is there a way to structure this activity so more students could participate?

- Some people might find demonstrating in front of the class stressful or scary. Are there ways in which Ben could structure his activity to make it less stressful or lower stakes?

Most of the literature suggests that best practice both for instructors and for students new to active learning is to ease into the practice. Bonwell and Eison (1991) recommend that, when possible, instructors assess students’ background knowledge on the topic ahead of time in order to plan activities at the appropriate knowledge and developmental level. Chapter 7 offers an overview of techniques for this kind of assessment. Bonwell and Eison also acknowledge that not all instructors are equally comfortable with all techniques, and advise instructors to begin with activities they find comfortable. Harris and Bacon (2019) note that more advanced learners find greater benefit from active learning, leading them to suggest that the activities should be scaffolded, meaning that the class should begin with easier, lower-risk activities while students are still learning basic content, and then gradually move to more complex tasks as learners develop mastery.

Examples of Active Learning Techniques and Strategies

Literally dozens of examples of active learning techniques and strategies exist. Part III of this textbook will offer more details about designing and implementing instruction sessions, including active learning strategies. This section provides short descriptions of some of the more popular activity examples, with a focus on those most suited to a typical library instruction session.

Think-Pair-Share

Perhaps one of the most widely recognized active learning techniques, think-pair-share can be used in classes of all sizes, with all different ages. Because it requires learners to interact only with one other person, it is relatively low risk even for introverted or anxious students. In this activity, instructors pose a question or provide another prompt such as a brief scenario. Next, they pause for a minute or two, giving students time to think about their responses. Students might just reflect or might jot down their thoughts. After a few minutes, learners pair up with a peer to share their responses and discuss their thoughts and reactions. Instructors might also encourage students to identify any questions that arose for them. Depending on the size of the class, the instructor might have each student share thoughts with the class or ask for a few volunteers to share ideas from their discussion with the whole group.

Discussion

Discussions are another popular and well-known active learning technique. Discussions can be carried out in large- or small-group formats, although smaller groups are generally more conducive to in-depth discussions and allow for more student participation. During discussions, learners reflect on and respond to readings, questions, or other prompts. Specific implementation strategies are detailed in Chapter 10.

Brainstorm/Carousel Brainstorm

Brainstorming activities encourage students to identify anything they can think of related to a topic. These activities can be done individually, or students can work in groups to pool their knowledge. A fun variation on a collective brainstorm is the carousel brainstorm. In this version, the teacher identifies different aspects or subtopics of the subject under study, perhaps posted on large sheets around the room. Small groups of learners are assigned to brainstorm a single subtopic. After a few minutes, the groups rotate to a new subtopic and add what they can to the previous group’s work. When each group has had a turn at each subtopic, the original group reviews and synthesizes the full class brainstorm of their subtopic and presents the information to the class. Activity 4.3 is an example of a brainstorming activity.

Activity 4.3: Instruction Brainstorm

Choose an information setting in which you would like to work and a patron group you would likely encounter there. Brainstorm as many different instruction topics as you can that would be relevant to that group and setting. You might extend the brainstorm by thinking of active learning techniques that could be used to learn about those topics.

Pair up with a classmate and exchange brainstorms. Review your peer’s paper and see if you can add any additional topics or active learning techniques.

Concept Mapping

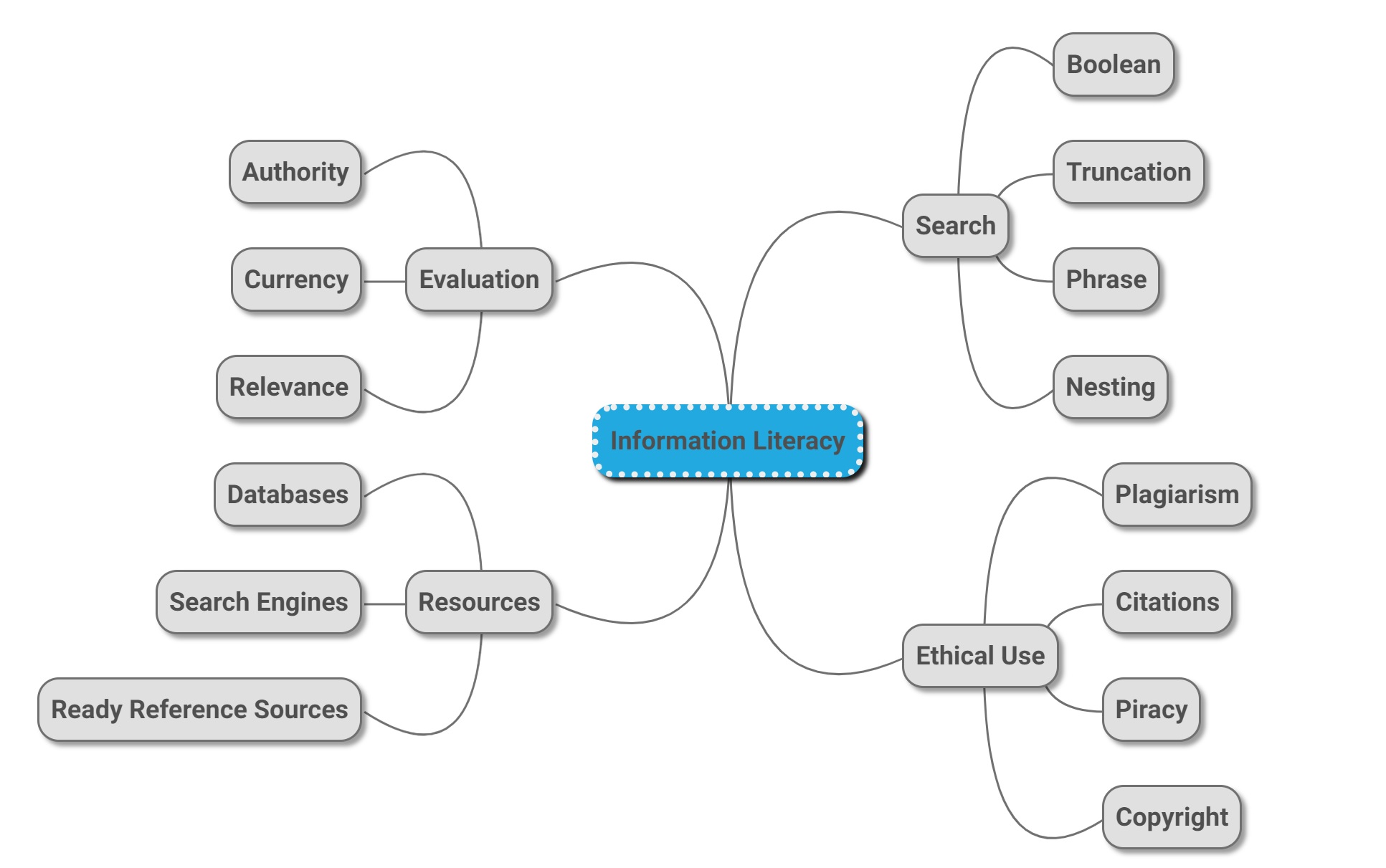

In concept mapping, learners create visual displays of the connections or relationships among ideas. Generally, a learner will begin with a single idea and brainstorm to identify other words and concepts, which they arrange around the original idea, with lines illustrating how the concepts relate. The new words might describe subtopics, broader topics, and related topics. Depending on the original idea, students might identify research questions on the topic, audiences concerned with or impacted by the topics, action steps, and so on. Concept maps are a great activity for students who are just beginning a research paper, as they can help identify areas of focus, as well as keywords and synonyms for searching. Concept mapping can be created by individuals or groups. Figure 4.1 shows a concept map of information literacy terms created by using the free tool MindMup.

Figure 4.1: Information Literacy Concept Map

Student Demonstration

Rather than lecturing or leading the class through a demonstration, we can turn the class over to the students to show one another how to work through a particular task or problem. For instance, a library instructor could ask learners to demonstrate the steps they took to locate a book or article, or to share the criteria they used to evaluate a website. This way, the learners take on a teaching role, and the instructor can act as a coach from the sidelines, offering feedback or suggestions if the learner gets stuck. One drawback of student demonstrations is that unless the class is very small or a significant amount of time is set aside, it is unlikely that all students will have a chance to demonstrate. A workaround might be to have students work in small groups or pairs.

Jigsaw

The jigsaw activity has students assigned to groups, with each group working on a different aspect of a larger project. Once groups complete their assigned task, the instructor shuffles the students into new groups comprising at least one representative from each of the initial groups. In this new group, learners piece together the work from their original groups to complete the larger project. The jigsaw is a collaborative effort, and each student has a chance to act as an expert or instructor when bringing the knowledge from the original group to the new group. As an example, imagine a class of second graders doing a unit on the life cycle of the frog. The librarian could create groups and ask each group to research and describe one stage of the cycle. Once the groups have completed this task, the instructor would create new groups with at least one student from each of the stages. Now, the new groups could compile their research and present a completed life cycle.

Role Play and Skits

Role playing can be an effective way for learners to test their skills and abilities with the kinds of roles or positions they anticipate encountering in the real world. Role playing requires students to think on their feet and draw on the ideas or knowledge they have acquired to address a problem or issue. This technique is often associated with professional programs such as nursing, where students might take turns playing the nurse and patient roles to practice doing a patient intake. However, this technique can be effective in many classrooms. For instance, a public librarian leading a session on job hunting could have students pair off and answer sample interview questions. Because role playing requires spontaneous thinking and interacting with peers who might or might not be familiar, it can feel a little risky, especially for shy students. Giving people time to get to know one another and keeping the activity low stakes can help make the experience more comfortable. Skits are a variation on role playing, in which learners develop a brief play illustrating a relevant situation, scenario, or process to act out in front of the class. For instance, after having students role play a job interview in pairs, the instructor could have learners finalize a script and perform for the class, opening up opportunities for wider discussion and more peer feedback.

Lecture Pause

Described briefly earlier, the lecture pause is a relatively easy technique to integrate and can work well even in very large classes. Using this technique, the instructor will pause every so often during the lecture to allow students to reflect on their learning. During the pause, the instructor might ask students to jot down the key points of the lecture, answer a specific question, or generate their own questions about the material. Students can work individually or pair up to share their reflections and answers. Pairing up can be effective, as learners might be able to answer one another’s questions, or fill in gaps in each other’s recollections of key points.

Peer Instruction

Instructors will often find they have classes of mixed abilities. Some students will be familiar with certain content, while for others it will be completely new. Instructors can find it challenging in such circumstances to present material in a way that is not too advanced for some or too easy (and likely boring) for others. This is common in public libraries where learners self-select into a session, and in academic libraries, where library instruction often is not fully integrated into the curriculum. Because some faculty request library instruction regularly, while others might never have a librarian visit their class, in any one class we will find some students who have sat through multiple similar sessions and some for whom this is a first. Peer instruction can be effective for such mixed classrooms. Instructors can pair or group learners who have more experience with the content together with those who have less, allowing the experienced students to do some of the instruction. Not only is this approach more engaging for all involved, but it has the added benefit that teaching is actually a great way to reinforce knowledge. The students engaging in instruction are deepening their own learning even as they offer instruction. While this approach can be ideal for groups of mixed levels, it is not always necessary for the students doing instruction to be more knowledgeable or advanced. After introducing a new concept or skill, instructors could have students take turns explaining or demonstrating for one another what they have just learned. In all cases, the instructor should stay engaged and offer feedback or redirect if the peer instructors are providing inaccurate information.

Minute Paper

The minute paper is a brief activity that asks students to reflect on their learning by taking roughly one minute to react to the day’s lesson. Instructors often guide the reflection by asking students to recall one or two new things they have learned and/or to identify the “muddiest point” of the lesson, or the section they found most confusing or about which they still have questions. This activity can be done anonymously, thus keeping stakes low and allowing students to be more honest in their reflection. If time allows, the instructor can review the papers and address some of the outstanding questions before the class ends. Another option is to have students add their name to the paper, and then return the paper with comments and answers to questions. The minute paper takes very little class time and can be done in classes of any size.

Scavenger Hunt

A scavenger hunt can be a great way to introduce people to the layout, services, and materials of the library. As in any scavenger hunt, participants in a library scavenger hunt will receive a list of items to find within the physical library. Rather than objects, this list could include recording the call number of a certain item, getting a pass signed by a reference librarian, or checking out a book. Participants could work individually or in teams.

This list is only a small sampling of active learning activities, and each of these has many possible variations. One of the best things about active learning is that it is not only engaging for the students, but it allows the instructor to be creative as well. As discussed in Chapter 9, many active learning techniques can also double as assessment tools, as the activities require students to demonstrate knowledge and ability. See Activity 4.4 for a brief activity on implementing active learning techniques.

Activity 4.4: Integrating Active Learning Techniques

Below are several descriptions of library classroom settings. See if you can think of at least two active learning technique for each example. You do not have to limit yourself to the techniques described in this chapter. There are many more examples available online and in the literature. Do a quick web search and see what other ideas you can find.

- A high school librarian is teaching a class on how to spot “fake news.” By the end of the session, he wants his students to check the domain name of the site, research the author or organization that created the site, and use additional sources to verify facts.

- A public librarian is running a workshop on online safety and privacy, which includes setting up a password manager. Her audience is mostly adults with at least a high school education.

- A college librarian is teaching a session for undergraduate students who have just been assigned a research paper. He plans to teach the students about Boolean operators and search limiters.

- A librarian at a legal firm is running a session to train lawyers on a new version of Westlaw. A few of the staff members who graduated recently are already familiar with this version from their law school.

Conclusion

Active learning is widely considered a best practice in teaching and learning, and both instructors and learners find active instructional strategies more engaging. Although active learning shifts much of the responsibility for learning from the instructor to the student, these techniques take at least as much planning and involvement on the part of the instructor as more traditional strategies like lecture. However, the work involved in active learning can offer great returns in the form of increased motivation and learning.

The major takeaways from this chapter are:

- Active learning techniques involve students directly with the content and can lead to deeper learning.

- An array of active learning techniques exists, with varying levels of complexity, the amount of class time they require, and whether they are intended for group or individual work. This variety and flexibility mean that active learning can be integrated into virtually any lesson, regardless of the size of the group, the amount of content to be covered, or the length of the session.

- Active learning techniques such as think-pair-share and lecture pause can be adopted even in large, lecture-based courses.

- Instructors new to active learning might start with brief, more simple techniques such as think-pair-share.

Suggested Readings

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques. Jossey-Bass.

This classic handbook offers myriad examples of active learning techniques. Although they are presented as methods of assessing student learning, the strategies in this book could be used as classroom activities as well, and most could be easily adapted for online sessions. A selection of 50 activities from this book are available at no cost online from the University of San Diego. (https://vcsa.ucsd.edu/_files/assessment/resources/50_cats.pdf)

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. Association for the Study of Higher Education (ED336049). ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED336049

Another classic text, this brief monograph provides a clear overview of a variety of active learning techniques, including problem solving, case studies, games, and peer teaching. The section on computer-based learning is extremely dated, but other techniques continue to be relevant. Bonwell and Eison also summarize the benefits of and challenges to implementing active learning.

Brame, C. (2016). Active learning. Vanderbilt Center for Teaching. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/active-learning/

This teaching guide from Vanderbilt University gives a clear and concise overview of active learning, including its theoretical basis, and research into its effectiveness. The author also gives several examples of active learning activities and advice on how to implement them.

Harrington, C., & Zakrajsek, T. (2017). Dynamic lecturing: Research-based strategies to enhance lecture effectiveness. Stylus Publishing.

In this volume, authors Harrington and Zakrajsek make the case that lectures can be active and engaging. They offer clear, research-based advice on how to plan, structure, and deliver a lecture that engages learners and incorporates activity and reflection.

Hinson-Williams, J. (2020). Active learning in library instruction: Getting started. Boston College Libraries. https://libguides.bc.edu/activelearning/gettingstarted

This LibGuide is an excellent resource for library instructors interested in integrating active learning into their sessions. The guide offers an overview of a range of active learning activities, organized by the amount of class time they take to implement. Additional tabs provide guidance on choosing an activity based on learning goals, and a short list of tech tools for active learning.

University of San Diego, Student Affairs. (n.d.) 50 classroom assessment techniques by Angelo and Cross. https://vcsa.ucsd.edu/_files/assessment/resources/50_cats.pdf

This freely available resource offers a brief overview of 50 of the active learning techniques described in Angelo and Cross’ (1993) classic handbook of classroom assessment techniques cited above.

Walsh, A, & Inala, P. (2010). Active learning techniques for librarians: Practical examples. Chandos Publishing.

This book offers examples of over three dozen active learning techniques for the library classroom. Each technique is outlined with its uses, required materials, notes, advice on how to implement it, suggestions for variations, and pitfalls to avoid. Activities are organized by those meant to be used at the start, middle, or end of a lesson. Separate sections offer tech tools and a set of lesson plans.

References

Bernstein, D. A. (2018). Does active learning work? A good question, but not the right one. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 4(4), 290-307. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000124

Berry, L. Jr. (1991). Collaborative learning: A program for improving the retention of minority students (ED384323). ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED384323

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom (ED336049). ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED336049

Cattaneo, K. H. (2017). Telling active learning pedagogies apart: From theory to practice. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 6(2), 144-152. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2017.7.237

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles of good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 3-7 (ED282491). ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED282491

Cohen, M., Buzinski, S. G., Armstrong-Carter, E., Clark, J., Buck, B., & Rueman, L. (2019). Think, pair, freeze: The association between social anxiety and student discomfort in the active learning environment. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 5(4), 265-277. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000147

Cooper, K. M., Downing, V. R, & Brownell, S. E. (2018). The influence of active learning practices on student anxiety in large-enrollment college science classrooms. International Journal of STEM Education, 55(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0123-6

Frederickson, E. (1998). Minority students and the learning community experience: A cluster experiment (ED423533). ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED423533

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 111(23), 8410-8415.

Graffam, B. (2007). Active learning in medical education: Strategies for beginning implementation. Medical Teacher, 29(1), 38-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590601176398

Hake, R. R. (1998). Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: A six-thousand student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics, 66(1), 64-74. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.18809

Harrington, C., & Zakrajsek, T. (2017). Dynamic lecturing: Research-based strategies to enhance lecture effectiveness. Stylus Publishing.

Harris, N., & Bacon, C. E. W. (2019). Developing cognitive skills through active learning: A systematic review of health care professions. Journal of Athletic Training, 14(2), 135-148. https://doi.org/10.4085/1402135

Lorenzo, M., Crouch, C. H., & Mazur, E. (2006). Reducing the gender gap in the physics classroom. American Journal of Physics, 74(2), 118-112. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.2162549

Miller, M. (2019, September 8). Active learning, active pushback, and what we should take away from a new study of student perceptions. Medium. https://medium.com/@MDMillerPHD/active-learning-active-pushback-and-what-we-should-take-away-from-a-new-study-of-student-8c208cb278fd

Monahan, N. (2017). How do I include introverts in class discussion? In Active learning: A practical guide for college faculty. Magna Publications.

National Institute of Education. (1984). Involvement in learning: Realizing the potential of American higher education (ED246833). ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED246833

Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93(3), 223-231. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2004.tb00809.x

Rainey, K., Dancy, M., Mickelson, R., Stearns, E., & Moller, S. (2019). A descriptive study of race and gender differences in how instructional style and perceived professor care influence decisions to major in STEM. International Journal of STEM Education, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-019-0159-2

Thomas, T. (2009). Active learning. In E. F. Provenzo (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the social and cultural foundations of education. Sage Publications.

Uemura, K., Yamada, M., & Okamoto, H. (2018). Effects of active learning on health literacy and behavior of older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(9), 1721-1729. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15458