20 Coordinating Instructional Programs

Introduction

When starting out, most instruction librarians will focus on developing and delivering their own individual instruction sessions. At some point, however, many of us will be asked to participate in planning and assessing a broader curriculum, and some might find ourselves in charge of our institution’s instructional program. Managing instruction at the program level involves setting program-level learning outcomes, reviewing the full curriculum to see how well it meets user needs, and assessing and evaluating the program. This chapter offers a brief overview of the basics of instructional program management.

Curriculum Planning: Backward Design

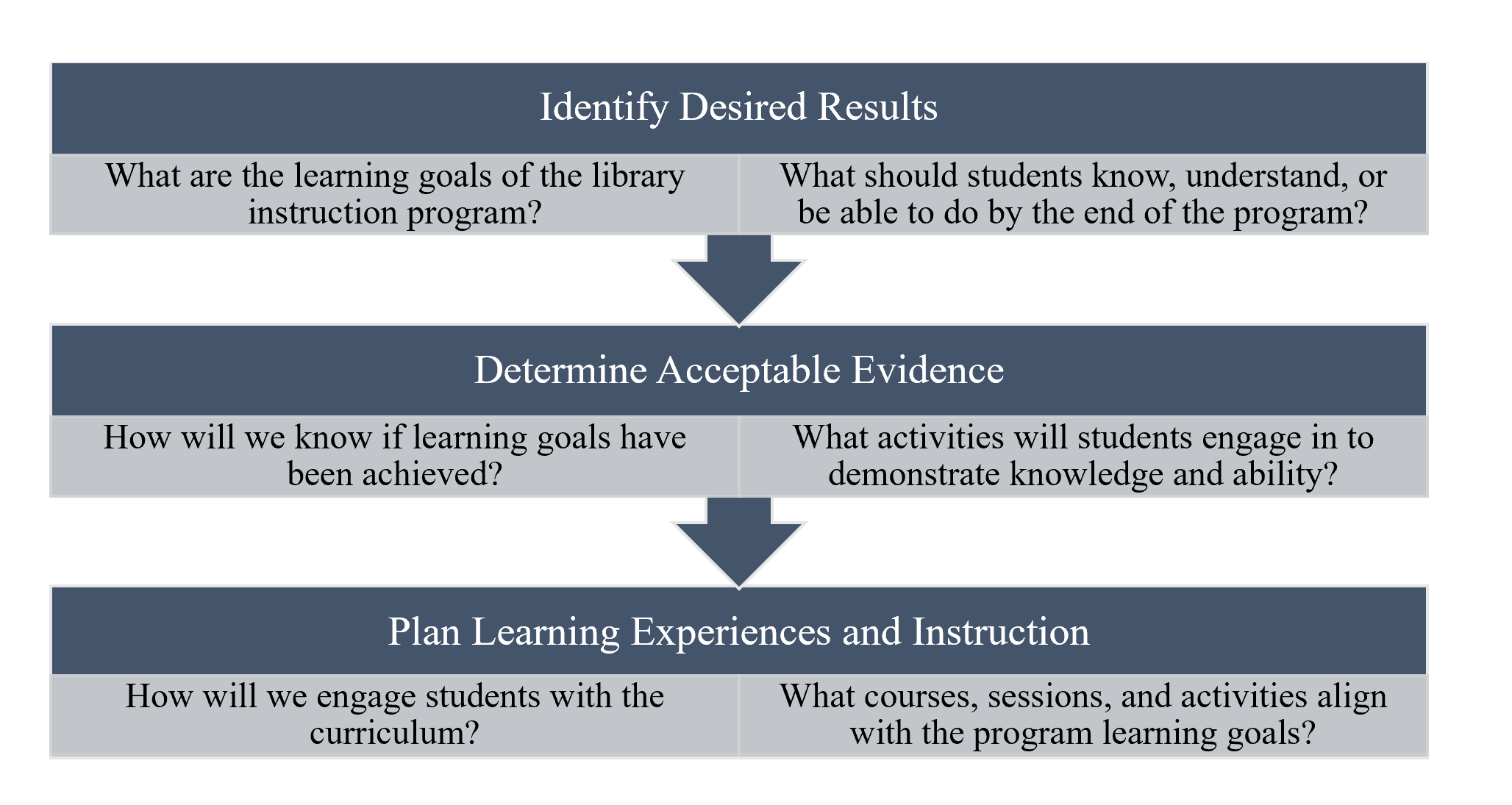

The first step to program management is planning the curriculum. Luckily, the steps for doing this are virtually the same as those for planning a single instruction session. In fact, Backward Design (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005) was developed with unit- and course-level development, rather than single-lesson development, in mind, and the steps involved can be easily applied to program-level planning. As a quick review from Chapter 8, the three stages of Backward Design are (illustrated in Figure 20.1):

- Identify desired results

- Determine acceptable evidence

- Plan learning experiences and instruction

Figure 20.1: The Stages of Backward Design

Identify Desired Results

The major difference in developing program outcomes as opposed to outcomes for a single lesson is one of scale. When designing single sessions, we develop learning outcomes appropriate for the time constraints of that lesson. At the program level, we can develop broader outcomes because we are now describing what learners will know, understand, or be able to do after engaging in a series of sessions that can build on each other and address a wider range of topics. We can draw on existing course- or session-level outcomes to extrapolate our program-level outcomes, as outcomes across various sessions will imply the broader skills and knowledge learners are intended to develop when these sessions are combined. For instance, learning outcomes related to Boolean, proximity, and subject searching in individual sessions imply that, ultimately, learners should be able to apply and combine search commands to develop effective search strings. While program-level outcomes will be broader than those at the session level, they should still be clear, specific, and measurable, as we will need to assess the learning at the program level just as we would at the session level. As always, the outcomes should be appropriate to our audience and setting. See Activity 20.1 for an example and activity on developing program-level learning outcomes.

Activity 20.1: Developing Program-Level Learning Outcomes

Often, we can develop program-level learning outcomes by extrapolating from session-level outcomes. The table below shows sample session-level learning outcomes from various types of instruction sessions, along with their setting and intended audience. Try to write an appropriate program-level outcome related to each, following the example given.

| Setting and Audience | Session-level Outcome | Program-level Outcome |

| College undergraduates |

|

|

| Public library jobseekers |

|

|

| High school students |

|

|

| College undergraduates |

|

We can also use professional standards and curricular frameworks as guides to what our students should be learning, as described in Chapter 2. Remember that these standards and frameworks are already written at a broad level. For instance, the Association of College & Research Libraries’ (ACRL) Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (2016) describes the information literacy competencies an individual might expect to have upon finishing an undergraduate degree program, while the American Association of School Librarians’ (AASL) National School Library Standards (2018) are meant to apply throughout K-12 education. When drawing on standards like these to create program learning outcomes, we need to consider our audience and the scope of our program. Are we describing outcomes for students in a certain year of high school or college, or at the end of their entire high school or college degree program? We would not expect students to achieve the same learning outcomes at the end of their first year of college as we will expect of them when they are seniors, but in both cases we can begin with the ACRL Framework to determine what learners should know and be able to do.

Determine Acceptable Evidence

Once we have our program learning outcomes, we must decide how we will assess achievement of those goals. According to Backward Design, at this stage we identify activities or assignments through which learners could demonstrate their learning. As described in Chapter 9, we can find or develop activities that align with our learning outcomes, have students complete those activities, and then collect and analyze the results for evidence of learning. In order to assess at the program level, we collect and analyze data across sessions and over longer periods of time, such as a semester or year, to get a picture of learner achievement across the program.

Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction

The final step in Backward Design is determining how the instruction will be delivered. For individual sessions, we plan specific learning activities such as a discussion or exercises for hands-on practice. At the program level, we will focus on the series and sequence of classes needed to achieve our outcomes. Most importantly, we need to ensure that we are offering an appropriate range of sessions, each with its own appropriate set of outcomes and learning activities, so that learners completing those classes will be able to demonstrate the program-level outcomes.

Scaffolding and Curriculum Mapping

When planning our instruction program, we should consider scaffolding, or sequencing sessions, so that learners are exposed to more complex information to build their skills and knowledge over time. Just as we would do within a session, we should examine our program to understand where certain skills are introduced, how they can be built on or reinforced, and whether there is a clear path for students to fully achieve the program-level goals. One way to conduct this type of review is through curriculum mapping.

Briefly, a curriculum map is a way of charting the “what” and “when” of the instructional program (Burns, 2001) by aligning instruction sessions with program learning goals, and illustrating how classes and other offerings build toward achievement of those goals. Often, these maps are laid out as tables or spreadsheets, with program-level learning outcomes listed across the top, and individual instruction sessions listed in the first column. Instructors can then use the appropriate table cell to indicate if a specific outcome is addressed in that course. These maps might also identify the level of learning happening in each session. Typically, the maps identify learning levels as “introduced,” “reinforced,” or “mastered,” depending on the expectations for student ability at the end of that session, although any terminology could be used. Once completed, these maps provide a visual overview of how current instruction sessions align with program goals, whether a clear path to attainment of learning goals exists, and where the gaps are. School and academic librarians also use curriculum maps to illustrate how their instruction supports academic programs by mapping information literacy courses to departmental learning outcomes rather than, or in addition to, library-determined learning outcomes (see, Charles, 2015; Howard, 2010; LeMire & Graves, 2019; Webb, 2020). Table 20.2 is an excerpt of an information literacy curriculum map.

Table 20.2: Curriculum Map Excerpt

| Apply search strategies to create efficient and effective search strategies. | Critically evaluate information to select appropriate resources to accomplish tasks and assignments. | Cite sources appropriately using standard citation style. | |

| IL100 Intro to Searching | I | ||

| IL110 Advanced Searching and Popular vs. Scholarly Articles | R | I | |

| IL200 Authority and Peer Review | R | ||

| IL300 Introduction to APA citation style | I | ||

| IL400 Evaluating Research Reports | M |

Program Assessment

As noted above, part of Backward Design involves planning for assessment, including identifying relevant activities and assignments that demonstrate student learning. Our purpose with program-level assessment is to measure the extent to which all learners are achieving the outcomes we set or, put another way, how well our program is enabling achievement of those outcomes. Session-level assessment tells us how well individual students are performing within a class and can give us a sense of how well the group assembled for that lesson achieved the session goals; however, without program-level assessment, we cannot see how the community of learners is performing nor whether we are successfully meeting our stated program-level learning goals.

For librarians, gathering evidence for assessment can be more challenging at the program level than at the session level. Unlike teachers in a degree program, librarians typically are not in a position to assign the types of activities like capstone projects or portfolios that require students to synthesize and apply skills and knowledge they have developed over the course of a program. In a school or academic library, if the parent institution has identified learning outcomes related to information literacy for all students, or if individual subjects or degree programs have their own information literacy outcomes, librarians might be able to work with faculty to access capstones, theses, and other culminating projects that integrate those outcomes to assess for information literacy. Otherwise, we will probably have to draw on and aggregate work produced in our individual sessions to assess at the program level. We can use our curriculum map to locate instruction sessions that address specific outcomes at a mastery level, and then identify the activities or assignments from that session that align with the outcome.

The next step is to gather the identified assignments or activities, or a sample of those activities and assignments, for review. Remember that our purpose at the program level is to get an overview of how well our community of learners is achieving program-level goals, not to scrutinize or provide feedback to individual students; that is done at the session level. In fact, some programs opt to anonymize assignments and activities before engaging in program review to protect students’ privacy during secondary analysis and to avoid any bias if the student is known to the reviewer.

Rubrics can greatly facilitate the review process at the program level (see Chapter 9 for more on rubric design). Ideally, rubrics should be developed specifically for the program-level outcomes. As with the session level, program-level rubrics should describe three levels of learning, typically, “exceeds expectations,” “meets expectations,” and “does not meet expectations.” In general, when we complete the assessment, we want to see the bulk of students meeting expectations, with some smaller percentage exceeding or not meeting, so that if we plotted the scores out on a graph, we would see a normal curve. Within our own programs, we can establish benchmarks or a minimum percentage of students we want to see meeting or exceeding expectations.

In addition to assessing whether learners are achieving program-level learning outcomes, we can use our review of activities to assess the efficacy of our various instruction sessions. We can gather activities from a specific session or series of sessions over a certain time period and review the activities to determine whether that session or series is effective. For instance, a public library that consistently offers a series of technology workshops could gather activities from those sessions for a six-month period and review them to determine if the classes are meeting their goals. If gaps are found, the program manager might make recommendations for revisions to the session. As explained in Chapter 9, assessment activities should be iterative, meaning that we return and reassess on a regular basis. When revisions are made to a course or session, iterative assessment helps us understand if those revisions were effective.

Program Evaluation

Chapter 13 discusses evaluation of individual instruction sessions. However, evaluation can also be carried out at the program level, and in an era of increased scrutiny and accountability, many of us will probably be asked to conduct or contribute to a program evaluation at some point. As with program-level assessment, evaluating programs allows us to see patterns and identify gaps in order to improve services, provide evidence of our value to stakeholders, and inform managerial decisions such as allocation of funds and staff.

To an extent, some of the techniques for individual evaluation described earlier in Chapter 13 can be aggregated as part of a program review. For instance, we could compile survey results from all of our workshops over the course of a semester or year to get a picture of learners’ perceptions of our instruction program as a whole. Similarly, we could look across the short-text responses from multiple sessions for patterns and themes. With regard to standards, librarians could look across lessons in a unit or series to see how well their programs address the full standards, and whether content and skills are appropriately scaffolded across sessions.

Most libraries and information centers will track attendance at instruction sessions. Especially in cases where learners choose to attend sessions, such as public library workshops, we might want to track attendance by time of day, day of the week, and session topic to get a sense of the distribution of attendance, which can help us plan for future workshops. In school and academic settings, where librarians might be dependent on faculty invitations to provide instruction, we can track requests by department, which can help us plan outreach. If we create online learning objects such as videos, tutorials, and library guides, we can use web analytics to track usage of these resources. It is important to note that while these numbers can help us evaluate the impact and reach of our programs, they do not measure quality or learner satisfaction.

General Administration and Management

Program managers will often have responsibility for overseeing the administrative and logistical details of the instruction program. The specific areas of responsibility will vary by institution but will generally include managing staff, including setting schedules, establishing policies and procedures, and communicating with stakeholders. In some settings, program managers might also administer their own budget, and manage facilities and equipment like instruction classrooms and makerspaces. This section will provide a brief overview of some of the major areas of program management. More in-depth information is available in the Suggested Readings at the end of the chapter.

Staff

Depending on the size and organizational structure of the library, the program manager might be a department head with dedicated staff or might act as a coordinator or team leader. As a department head with direct reports, the program manager will likely be responsible for hiring new instruction librarians. Even if the library director makes the final hiring decision and negotiates the offer, the instruction program manager will be involved in writing the job description, reviewing applications, and setting up and conducting interviews. Crafting a good job description is a crucial step in hiring, as the description will not only influence who applies for the job but will also serve as a guide for setting goals and conducting reviews once the new person is in place. The challenge in writing job descriptions is to delineate between essential knowledge and skills that a person should bring to the position on day one, and the knowledge and skills that we might prefer them to have on day one but could be developed on the job.

In addition to a standard résumé and cover letter, many institutions ask applicants to submit documents, such as a teaching statement, that speak to their teaching abilities. The vast majority also require invited applicants to do a presentation as part of their interview (Hall, 2013). The structure of the presentation varies by institution. Some ask applicants to discuss their experience and philosophy of teaching, or their perspective on an issue in the field, while others have the applicant prepare and teach an actual instruction session targeted to a specific outcome and audience. Either way, a presentation gives the hiring manager and staff a glimpse of the applicant’s teaching style and how it is put into practice, and as such is a good supplement to more standard interview questions. Some employers, especially in school settings, might also ask to see a portfolio of the applicant’s work, including sample lesson plans and class activities. See Activity 20.2 for an exercise on job descriptions.

Activity 20.2: Job Descriptions for Instruction Positions

Go to a job board like ALA’s JobList, and search for instruction positions for the type of information setting in which you would like to work. Try to find at least three postings. Read through the descriptions, and answer the following questions:

- What knowledge and skills are listed as essential, and which are preferred?

- Is there overlap in how the postings describe the positions and qualifications they require, or do they differ substantially? If they differ, why might that be?

- Does the posting ask for any supplemental materials beyond a résumé and cover letter? Why might that be?

Now, imagine you are the program manager in charge of hiring for this position:

- How would you prioritize the essential skills? That is, if applicants did not have all of those skills, or if some applicants had more experience in one area than another, which skills would you emphasize in hiring? Why?

- Are there any skills or qualifications you think are missing from the list?

- Are there any skills or qualifications included that you think are not essential, or should be preferred but not essential? Which ones, and why?

- Would you require applicants to do a presentation, and if so, how would you structure that presentation?

- Is there anything you would add to this posting or anything that you would change to make it align with your vision of an instruction position in this type of information setting?

Once a hire is made, the program manager will orient the new staff to the department, including reviewing policies and procedures, and lead them through any training program, which might include shadowing experienced instruction librarians and assisting in instruction sessions. During this process, the manager should review the position description, and work with the new employee to set professional development goals for the upcoming year. Those goals should align with the mission and priorities of the library and the instruction program but can be tailored to the individual person and position. For instance, if new employees have limited experience teaching online, they might set a goal to attend training and familiarize themselves with relevant software.

Program managers will likely also either conduct annual reviews with instruction staff or contribute to reviews done by higher-level administrators. Reviews should be both positive and constructive. We should acknowledge what our staff is doing well, but we also need to address any challenges or areas for growth openly and honestly. The aim with constructive feedback is not to just point out areas for improvement but also to identify strategies for improvement, such as training and professional development, shadowing a more experienced teacher, and opportunities for self-reflection. We should also review each staff member’s goals from the previous year, discuss achievements, and set goals for the upcoming year.

Scheduling

On a day-to-day basis, the program manager might administer logistics such as schedules and facilities. In some institutions, especially those which use a liaison model, in which librarians are assigned to directly support specific academic departments, liaison librarians might receive instruction requests from departmental faculty directly and manage their own schedules. In other cases, a program manager might receive all instruction requests and be responsible for assigning staff coverage and requesting classroom space as necessary.

Scheduling might seem like a straightforward process, but it involves more than just ensuring a librarian is assigned to every session. In addition to actual time spent in the session, we also have to calculate the time needed to prepare for a session, also known as “prep time.” Instructors, including library instructors, consistently cite a lack of planning time as one of the biggest challenges they face (Julien et al., 2018; Merritt, 2017). As a program manager in charge of scheduling, you will need to work with your staff to be sure that they have adequate prep time for their scheduled sessions.

The amount of prep time necessary for any session will vary depending on the experience and comfort level of the teacher and whether the instructor has already taught that material in the past, but a general rule of thumb is to plan one to two hours of prep time for every hour spent in class. If instructors have already taught a class before, they will still want to review their notes and perhaps update examples or test demonstrations. They might also need time to incorporate ideas for improvement from their assessments and evaluations of those previous sessions. If a session is completely new, instructors might need even more than two hours, as they will have to prepare the entire session, from identifying the learning outcomes to developing assessments and learning activities. If an instructor is visiting a class at the request of a faculty member, we might also build in time for them to talk about goals for the session.

Assuming that most library instructors will need about two hours of prep time for each hour in class, we can estimate how many hour-long instruction sessions per week our staff can handle. We can also try to manage the schedule so that sessions are balanced across staff in order to avoid burnout. Keep in mind that prep time does not have to be scheduled immediately prior to the instruction session. In fact, most instructors will want to plan their sessions days or even weeks in advance, and then take time to review the materials briefly just before the session.

Space

Program managers could be in charge of managing classroom space as well as the schedule. Some libraries have their own instruction space or another area that is often used for educational programs like a makerspace. Part of scheduling involves ensuring that the sessions do not overlap and that the appropriate groups have access to the space as needed. If the library has its own classroom, the program manager might be consulted about layout and equipment needs for that space. Ideally, as discussed in Chapter 6, we should develop a space with attention to universal design principles, including adequate space within the classroom for wheelchairs and other assistive devices, flexible furniture, adjustable lighting, and appropriate assistive technology. Even when we do not have direct control over our classroom space, or lack the budget to renovate our space, we can take steps to make the classroom comfortable and accessible for our learners and our instructors. For instance, we might be able to move some furniture to make wider aisles or to provide space at workstations for wheelchairs, arrange seating at the front of the room for learners with visual or hearing disabilities, and adjust the lighting in the room, the volume of any audio materials, or the text size of screen displays as necessary (Thurber & Bandy, 2018).

Mission, Policies and Procedures

As program managers, we are responsible for establishing, or helping to establish, a mission, policies, and procedures for our department. The mission statement describes the purpose, intentions, and goals of the instruction program as a whole, while the policies and procedures outline how the mission will be accomplished.

A mission statement is a brief summary of an organization’s or program’s philosophy. It provides a “foundation for the organization’s identity and purpose and helps focus the efforts of everyone involved to work toward the same goal while informing the public of its reason for existence” (Comstock, 2020). An instruction program mission statement should align with the mission and goals of the larger library and its parent organization. Within that framework, the instruction mission statement should identify and describe the primary audience(s) for instruction and the library’s goals in serving that audience, including the learning outcomes. For instance, a high school library would describe the student body as its primary audience, perhaps followed by teachers, administrators, and, possibly, parents. Goals for a high school library instruction program would probably include enabling students to fulfill academic requirements related to information literacy required for graduation and developing the information literacy skills students will need for success in college, work, and personal life.

Policies establish the guidelines for our practice. They set service expectations for patrons and guide staff in fulfilling those service expectations. As always, the specific set of policies will depend on the information setting but could include areas like program goals and priorities, types and modalities of instruction offered, and collaborative and outreach efforts.

Instruction policies might provide a more detailed overview of our intended audience and goals than what is found in the mission statement. By detailing the services offered, the policies will also describe how the instruction program will achieve its goals. Policies might describe the range of skills and knowledge areas covered by the instruction program. Further, these policies will likely outline the types of instruction offered, which could include in-person instruction both in class and at the reference desk or through research appointments; online (synchronously, asynchronously, or both); and through the development of learning objects like research guides and tutorials. The policy would likely also detail the kinds of services available to faculty, such as the ability to request an in-class session or a tailor-made research guide. The policy might also lay out any parameters for service requests. For example, the Healey Library (n.d.) policy at the University of Massachusetts Boston notes that “effective library instruction takes time to prepare and is in great demand” and asks that faculty submit requests for library instruction sessions at least two weeks in advance. If the library partners with other institutional or external organizations to deliver instruction, such as a public library working with local schools or academic libraries partnering with a career counseling center, the policy might provide an overview of those projects.

Procedures are the step-by-step processes for implementing our policies. For instance, a library that offers in-class sessions or creates research guides at faculty request should include a form explaining how to submit such a request. Likewise, librarians who are willing to partner with other offices or organizations should explain how interested parties can contact the library to set up a program. In general, librarians will do everything they can to meet the demand for their services, but in times of limited resources, some libraries might not be able to fulfill all incoming requests. In such cases, the library might also institute a policy and procedure for handling overwhelming demand.

Communicating with Stakeholders

All instruction librarians should be ready to take part in marketing as described in Chapter 19, but the program manager will usually take the lead in coordinating the marketing program and for sharing program-level information with stakeholders. Part of the process is identifying stakeholders and determining what they need or want to know. Stakeholders can be anyone who has a direct or indirect interest, or stake, in the library and, for our purposes, in the instruction program. Stakeholders would include learners, of course. If the learners are students in a school or college, others who could be considered stakeholders could be teachers, school or campus administrators, and even parents. Additional stakeholders include anyone with a financial interest in the library, including taxpayers, as well as those who provide budgetary oversight like city councilors, campus administrators, and boards of trustees.

Once we have identified stakeholders, we can determine what information would be of interest to them. For instance, teachers and faculty might be interested in how well students in their departments are achieving information literacy outcomes, while campus administrators and school boards might be interested in how well the full student body is achieving program-level outcomes. In a public library, city councilors and others might be as interested in learners’ satisfaction with current program offerings as they are with achievement of learning outcomes.

In our role as program administrator, we should analyze the program-level assessment and evaluation data to cull the information relevant to each stakeholder audience and find ways to package and share that information. As described in Chapter 19, we should be sure that we adapt the information to our audience. Students might be satisfied with a few tweets that share major findings from a program assessment, while campus administrators will probably prefer a brief report with charts and graphs to illustrate the data.

Setting A Vision

The responsibilities described thus far in this chapter could be considered mostly managerial. That is, they are focused on the administrative tasks necessary for the day-to-day running of the information literacy program. While managerial tasks are crucial, by themselves they lack a broader vision or plan for the program. Another role for instruction program managers is as a leader who helps set a vision for the program. Unlike a mission statement, which typically describes what the program intends to accomplish currently, a vision is forward-looking, and a vision statement describes what the program hopes to accomplish in the future, building on its strengths and resources (Comstock, 2020). What is the mission and value of our program? Why should staff and stakeholders care about it? How do we want our program to be viewed by the community? As a leader, rather than just a manager, we should consider these questions and then work with our staff and our community to answer them. To craft such a vision, we must be aware of the priorities of our larger community or campus and be monitoring the trends in field.

Furthermore, we have to work with our staff to cultivate support and enthusiasm for the vision. Why should the staff care about this vision? Why should they work toward it? How do their individual positions and efforts contribute to the program vision, and how does the program vision contribute to the mission and vision of our larger community and campus? As a leader, we have to help our staff see the answer to these questions. We also have to be responsive to our staff’s ideas and inputs. Remember that instruction staff are on the front lines of the service, delivering sessions, interacting with learners, and gathering assessment and evaluation data. They will have important insights about what is working and what is not, what learners and other stakeholders think about our current services and what they would like to see, and how well our resources and facilities support our instructional programming. As leaders, our role is to organically develop a vision of services, in concert with our staff, that is responsive to our community’s needs and cognizant of the challenges, issues, and trends in the field.

Conclusion

Many instruction librarians will be called on to manage an instruction program or contribute to its management. Program managers have a range of responsibilities that might take them out of the classroom but nevertheless will have a big impact on the goals and activities of the library instruction program. The major takeaways from this chapter are as follows:

- Program planning can largely follow the steps of Backward Design, beginning with developing learning outcomes, followed by identifying methods for assessment and planning instructional activities.

- The sessions within a library instruction program should be scaffolded to build more complex skills. Curriculum maps can show us how our current program enables learners to achieve program learning outcomes, and to identify gaps in the curriculum.

- Program-level assessment and evaluation involve aggregating the data from individual sessions to gain a broad overview of the larger community of learners’ achievement of learning outcomes and satisfaction with sessions.

- As program managers, we will likely oversee the day-to-day management of the program as well as provide a larger vision for what the program could accomplish in the future.

Suggested Readings

Buchanan, H., Webb, K. K., Houk, A. H., & Tingelstad, C. (2015). Curriculum mapping in academic libraries. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 21(1), 94-111. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2014.1001413

This article presents four examples of curriculum-mapping projects at four academic libraries. Each map is presented as a brief case study with an overview of how the steps for mapping were implemented, along with excerpts of the maps themselves and discussion of the results of the projects. The article begins with a solid introduction to curriculum mapping and includes a thorough bibliography. Although all four examples are from academic libraries, the steps could be applied to other settings.

Donham, J., & Sims, C. (2020). Enhancing teaching and learning: A leadership guide for school librarians, 4th ed. Neal-Schuman.

This extensive handbook addresses every aspect of a school library instruction program through the lens of management and leadership. In addition to an overview of stakeholders, including the students, principals, and the community, the book includes chapters on technology, literacy, collections, assessment, and evaluation. Each chapter includes a section on “leadership strategies” for that topic, while a concluding chapter provides a general overview of leadership qualities and how to lead from various positions.

Grassian, E. S., & Kaplowitz, J. R. (2005). Learning to lead and manage information literacy instruction. Neal-Schuman.

Written by two veteran library instructors, this handbook covers all aspects of library instruction program management, including staff training, evaluation and assessment, and outreach to stakeholders. Importantly, the book also addresses issues of organizational politics, including communicating with administrators and boards of trustees. In addition to these basic management topics, the authors also discuss fundraising and grant writing, important areas not covered in most other texts on library instruction. Although somewhat dated now, much of the advice is still relevant.

Sobel, K., & Drewry, J. (2015). Succession planning for library instruction. Public Services Quarterly, 11(2), 95-113. http://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2015.1016198

This article discusses the importance of succession planning, or ensuring that the library has a plan for continuity of service even as it deals with staff turnover. The authors discuss preparing instruction librarians to take on leadership roles, including providing them with professional development and training opportunities, and developing plans for tracking and sharing institutional knowledge.

Woodard, B. S., & Hinchliffe, L. J. (2002). Technology and innovation in library instruction and management. The Journal of Library Administration, 36(1/2), 39-55.

The authors draw on two theoretical frameworks of technological automation and the diffusion of innovation to examine how technology can be best used to support instruction and to facilitate management activities related to instructional programs. Despite its publication date, the article is still very relevant. The authors do not focus on specific technologies but use a high-level, theory-based approach to explain how to evaluate new technologies for adoption.

References

American Association of School Librarians. (2018). National school library standards for learners, school librarians, and school libraries. ALA Editions.

Association of College & Research Libraries. (2016). Framework for information literacy for higher education. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Burns, R. C. (2001). Curriculum handbook: Curriculum mapping. ASCD. http://www.ascd.org/publications/curriculum-handbook/421.aspx

Charles, L. H. (2015). Using an information literacy curriculum map as a means of communication and accountability for stakeholders in higher education. Journal of Information Literacy, 9(1), 47-61.

Comstock, N. W. (2020). Mission and vision statements. Salem Press Encyclopedia. EBSCO.

Hall, R. A. (2013). Beyond the job ad: Employers and library instruction. College & Research Libraries, 74(1), 24-38. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-236

Healey Library. (n.d.). Library instruction. University of Massachusetts Boston. https://www.umb.edu/library/info_for_faculty/instruction

Howard, J. K. (2010). Information specialist and leader—Taking on collection and curriculum mapping. School Library Monthly, 27(1), 35-37.

Julien, H., Gross, M., & Latham, D. (2018). Survey of information literacy instructional practices in U.S. academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 79(2), 179-199. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.2.179

LeMire, S., & Graves, S. J. (2019). Mapping out a strategy: Curriculum mapping applied to outreach and instruction programs. College & Research Libraries, 80(2), 273-288. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.80.2.273

Merritt, E. G. (2017). Time for teacher learning, planning critical for school reform. Phi Delta Kappan. https://kappanonline.org/time-teacher-learning-planning-critical-school-reform/

Thurber, A., & Bandy, J. (2018). Creating accessible learning environments. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/creating-accessible-learning-environments/

Webb, K. K. (2020). Curriculum mapping in academic libraries revisited: Taking an evidence-based approach. College & Research Libraries News, 81(1), 30-33. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.81.1.30

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. ASCD.