8 Establishing Learning Goals and Outcomes

Introduction

As instructors, we are probably excited to get into the classroom, but we might also feel overwhelmed by the idea of planning our session. How will we fill up the time? What material should we focus on? Will the students be engaged? When answering these questions, most instructors focus on what they will teach, often asking themselves what content they need to cover. This approach puts the emphasis on teaching, rather than learning, and often leads to sessions that are packed with too much information. In such cases, students may feel overwhelmed by the amount of material presented and fail to see connections between various parts of the lesson and among the discrete pieces of information. Learners leave these sessions without clear takeaways in the form of new knowledge, abilities, or skills.

Wiggins and McTighe (2005) argue that instructors can avoid these pitfalls through Backward Design, an approach to instructional design that encourages us to begin planning a class by thinking about what we intend students to know, understand, or be able to do by the end of the session. Only after these learning outcomes are established do we begin to think about what material we will teach, how we will teach it, and what methods we will use to determine if our lessons are successful. In each of these successive steps, we can return to the learning outcomes to ensure that the activities and assessments we select are relevant to our final learning goals. By beginning at the end, Backward Design centers on student learning. This chapter offers an overview of the Backward Design model and provides an in-depth look at the first step in the design process: developing learning outcomes or goals. The chapter discusses how to write clear learning outcomes, how to identify appropriate content, and how to make the outcomes relevant and meaningful to learners. Later chapters will address the next two steps on identifying assessments and learning activities.

Backward Design

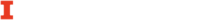

Backward Design is a three-stage approach to instructional design that shifts the focus of the design process from content and teaching to outcomes and learning (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). The three stages of Backward Design, shown in Figure 8.1 as well, are:

- Identify desired results

- Determine acceptable evidence

- Plan learning experiences and instruction

Figure 8.1: The Stages of Backward Design

Identify Desired Results by Writing Learning Outcomes

Before thinking about how we will teach, or even what we will teach, the Backward Design approach asks us to determine the intended results of the session by writing learning outcomes. Learning outcomes, sometimes called learning goals or learning objectives, “identify what a student should be able to demonstrate or represent or produce as a result of what and how they have learned … that is, they translate learning into actions, behaviors, and other texts from which observers can draw inferences about the breadth and depth of student learning” (Maki, 2010, p. 89). As part of course planning, we should explicitly define what students will know, understand, or be able to do at the end of the session, workshop, or course. Table 8.1 gives a few examples of learning outcomes related to library content areas.

Table 8.1: Learning Outcome Examples

| Content Area | Sample Learning Outcome |

| Searching |

|

| Evaluating information |

|

| Citing sources |

|

Determine Acceptable Evidence or Assessment

How will we know if students actually achieve the goals we set for our lesson? During stage two, instructors identify assessments, or activities, experiments, performances, or tasks in which students could engage to demonstrate their learning. These assessments provide us with data to measure student achievement of the learning goals. Table 8.2 provides some samples assessment activities drawing on the learning outcomes from Table 8.1. Chapter 9 offers an in-depth examination of assessment methods and techniques.

Table 8.2: Sample Assessment Activities

| Learning Outcome | Sample Assessment Activity |

| Implement Boolean operators appropriately to broaden and narrow searches. | Have learners brainstorm keywords related to a topic of interest. Ask learners to conduct a search online or fill out a worksheet showing how they would combine the terms using the operators and, or, and not. Ask learners to explain whether they expect each search string to bring broaden or narrow their search, and why. |

| Compare and contrast popular and scholarly articles.Recognize when citations are needed. | Provide learners with one scholarly and one popular article on the same topic. Ask learners to identify each as scholarly or popular, and list as many reasons as possible to support their decision. |

| Recognize when citations are needed. | Provide learners with a brief article, followed by sample passages from a research paper that quote the article, paraphrase it, and provide an original opinion; ask learners to identify which passages need citations. |

Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction

The third step is likely the one that first comes to mind for most of us when we think about teaching, and yet it is the last stage of Backward Design. According to Wiggins and McTighe (2005), we should begin to think about the specific content of the session and how that content will be delivered only after we have identified the learning outcomes and how those outcomes will be assessed. At this stage in the design process, instructors choose the specific instructional activities and teaching methods they plan to implement in the classroom or online, such as lectures, discussions, and active learning techniques. They plan the sequence of material and activities and think about the steps they will take to capture learners’ interest and keep them engaged throughout the lesson. The selection and implementation of instructional strategies is covered in depth in Chapter 10.

Why Backward Design?

Wiggins and McTighe refer to the three-stage approach as “Backward” Design because they ask instructors to begin their planning with the end of the lesson by identifying the results or outcomes of the instruction session. What knowledge or understandings will learners have gained through the session? What skills will they develop? While this approach might seem counterintuitive at first, the authors explain that identifying the intended results puts the rest of the session into perspective and ultimately should lead to a better session and better learning.

We can think of the process like taking a drive. If we have a destination in mind, we can plan our trip carefully to take the shortest route, avoid the traffic, or pass our favorite lunch spot. If we have additional goals, like arriving by a certain time or seeing certain sights, we can factor those goals into our planning as well. Arriving at our intended destination is evidence that we achieved our main goal, and we can also consider how well we met other goals along the way. Did we arrive on time? Did we pass the sights we intended to see? The clearer we are about what we want to accomplish, the better our planning can be. We could certainly go for a drive without a destination in mind, and the ride might even be enjoyable, but it will be harder to know if we accomplished anything because we did not have a clear goal. A number of case studies suggest that Backward Design is an effective approach (Shah et al., 2018; Shaker & Nathan, 2018) and might lead to improved learning (Hosseini et al., 2019; Yurtseven & Altun, 2017).

Wiggins and McTighe argue that using the Backward Design approach can help us avoid what they call the “twin sins” of coverage-based and activity-based instruction (2005, p.16). Coverage-based instruction is typically the result of instructors feeling pressure to cover a certain amount of content in a restricted time period. As a result, they pack as much content as possible into their sessions, often resorting to rigid lectures, without any direct engagement of the students, and potentially focusing more on discrete facts and ideas than on bigger concepts and questions. Such an approach ignores the cognitivist and constructivist theories that tell us that learners need to interact with content and with each other in order to make meaning and transfer information to long-term memory. While instructors in these classes might feel relieved that they “talked about” all of the necessary content, the question is whether students learned what they needed to learn.

The coverage-based approach impacts librarians just as it does any other instructor. When we know that the session we are leading might be our only interaction with some patrons, we are often tempted to cram as much information as possible into that single session. Indeed, the authors of this textbook have observed 50-minute library sessions in which the librarian has started with an overview of the library website, explained how to submit an interlibrary loan request, pointed out the chat reference link, demonstrated how to search the library catalog and at least one library database, while explaining keyword versus subject searching, Boolean operators, and nesting strategies!

On the other hand, some instructors focus so much attention on activities that the purpose and meaning behind those activities get lost. As we learned in Chapter 4, active learning is considered a best practice, and it aligns with theories of learning that emphasize the need for students to engage directly with material. However, if those activities are not clearly linked to learning outcomes, students might enjoy them and might acquire some basic facts and skills, but they are unlikely to see the connection between the new information they are learning and their existing knowledge. This could limit their ability to apply the knowledge and skills in new contexts or integrate them into their daily lives. As an example, we can spend an hour showing learners how to search library databases and giving them opportunities to practice searching on their own, but if they do not see the connection between that activity and their current search practices, they will probably go right back to Google when the session ends. We showed them how to search a database, but we did not help them to understand when or why to search a database, and in the end our instruction did not change their behavior. Identifying learning outcomes provides us and our students with context for the learning activities, helping to explain why we are engaging in those activities, and how the learning is relevant beyond the current session.

For instructors, learning goals provide us with the destination which helps us plan our road map. When learning goals are explicitly stated and shared, they help set learners’ expectations. Students will enter the session understanding what they are expected to learn. If learners are attending by choice, those outcomes can help them decide if the session is relevant and at an appropriate level for them. In addition, if learners understand what they were meant to learn in a session, they can engage in self-assessment by reflecting on their learning and monitoring whether they achieved the outcomes.

Writing Outcomes

Clear, strong, well-written learning outcomes are an essential part of instructional planning for both the instructor and the learners. Well-written learning outcomes have several elements. They should:

- Clearly identify what a student will know, understand, or be able to do by the end of a session.

- Be appropriate to the audience and time frame of the lesson.

- Be measurable.

The main purpose of learning outcomes is to describe what learners will gain by engaging with the instruction. Remember that we are describing what learners should understand and be able to do after the session is over, so it can help to think about the long-term needs and personal goals of our learners, rather than just the short-term goals of an assignment or task. What will be important for the learners to take away from the lesson? What do we want them to remember and be able to do when the lesson has ended and we are not there to guide or assist them? And what specific skills and knowledge do they need to achieve those goals? For instance, if we are running a session on using email, our learners will need to be able to set up an email account, create and send a message, and open incoming mail. College students writing a research paper will need to be able to search databases effectively and identify and evaluate scholarly information. Our learning outcomes should clearly reflect these skills and knowledge areas.

As we write our learning outcomes, we need to keep our audience and time frame in mind. Our learners will come with various levels of experience and background knowledge, and we want to ensure that our lesson is neither too challenging nor too easy. Using the techniques discussed in Chapter 7, we can learn about our audience members prior to the session and use that information to guide us in creating learning outcomes appropriate to their level of understanding and development.

We also need to consider how much time we have in our session, and how much time we need to devote to each outcome. The time required depends on the scope of the outcome; gauging the amount of time to spend on any one outcome is challenging, especially for new instructors. However, in general, we should be able to address three to four outcomes in a 60-minute session.

Part of the purpose of learning outcomes is to provide a goal against which to measure learning. To do this, the outcomes should describe the learning in terms of observable actions or performances that will allow students to demonstrate that learning. Vague, unclear, or overly broad goals are hard to measure, so clear and precise language is important. The next section explains how to craft clear and measurable outcomes.

Using Active Verbs

Learning outcomes should be written with active verbs that describe with precision what a learner will know or be able to do by the end of the session. Often, outcomes are written as bulleted phrases that follow an opening statement, such as “By the end of this session (or course, workshop, tutorial, etc.) learners will be able to …” Each phrase following that statement begins with an active verb such as “examine,” “analyze,” “discuss,” or “create.” Within this construction, “the verb generally describes the intended cognitive process, and the noun generally describes the knowledge students are expected to acquire or construct” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001).

One verb that instructors are discouraged from using when writing learning outcomes is “understand,” along with similar verbs and phrases such as “know” and “be familiar with.” As Wiggins and McTighe (2005) explain, these verbs and phrases are often used imprecisely and do not clearly convey the expected learning. For instance, suppose one of the learning outcomes in a library session is for students to “understand Boolean operators.” If the learners are able to name the three Boolean operators, does that mean they understand them and have achieved the outcome? Most of us would probably argue that it does not. Just because students can list the operators does not mean that they can explain how they work or use them correctly to broaden and narrow searches. So, when we use the word “understand” with regard to learning, we often mean something deeper and more complex than a recall of facts. However, that deeper and more complex meaning is not clearly conveyed by the word “understand” and, most importantly, students might believe it to mean recall of facts.

More precise language clarifies expectations for learners and leads to better and easier assessment in stage two of the Backward Design process. Going back to the Boolean operator example, rather than saying students will “understand” Boolean operators, we might identify outcomes like students will be able to “explain” the purpose of Boolean operators and “apply” them appropriately to broaden and narrow searches. Table 8.3 provides some examples of poorly written and strongly worded outcomes, and Activity 8.1 offers a brief related exercise.

Table 8.3: Examples of Poorly Written and Strongly Worded Learning Outcomes

| Poorly Worded | Strongly Worded |

| Be able to search databases | Apply Boolean search strategies effectively to broaden and narrow searches. |

| Evaluate a website | Evaluate websites for authority, reliability, and accuracy; identify trustworthy sites. |

| Understand how databases work | Describe how information is parsed and stored in a database. |

| Understand primary sources | Define primary, secondary, and tertiary sources; identify examples of each. |

Activity 8.1: Writing Strongly Worded Learning Outcomes

Drawing on the examples of poorly written and strongly worded learning outcomes from Table 8.3, try to rewrite the following poorly worded outcomes to strengthen them:

- Find scholarly articles

- Learn to use Overdrive

- Understand call numbers

Questions for Reflection and Discussion:

- What made the poorly worded questions weak?

- How did the rewrites improve them?

Bloom’s Taxonomy

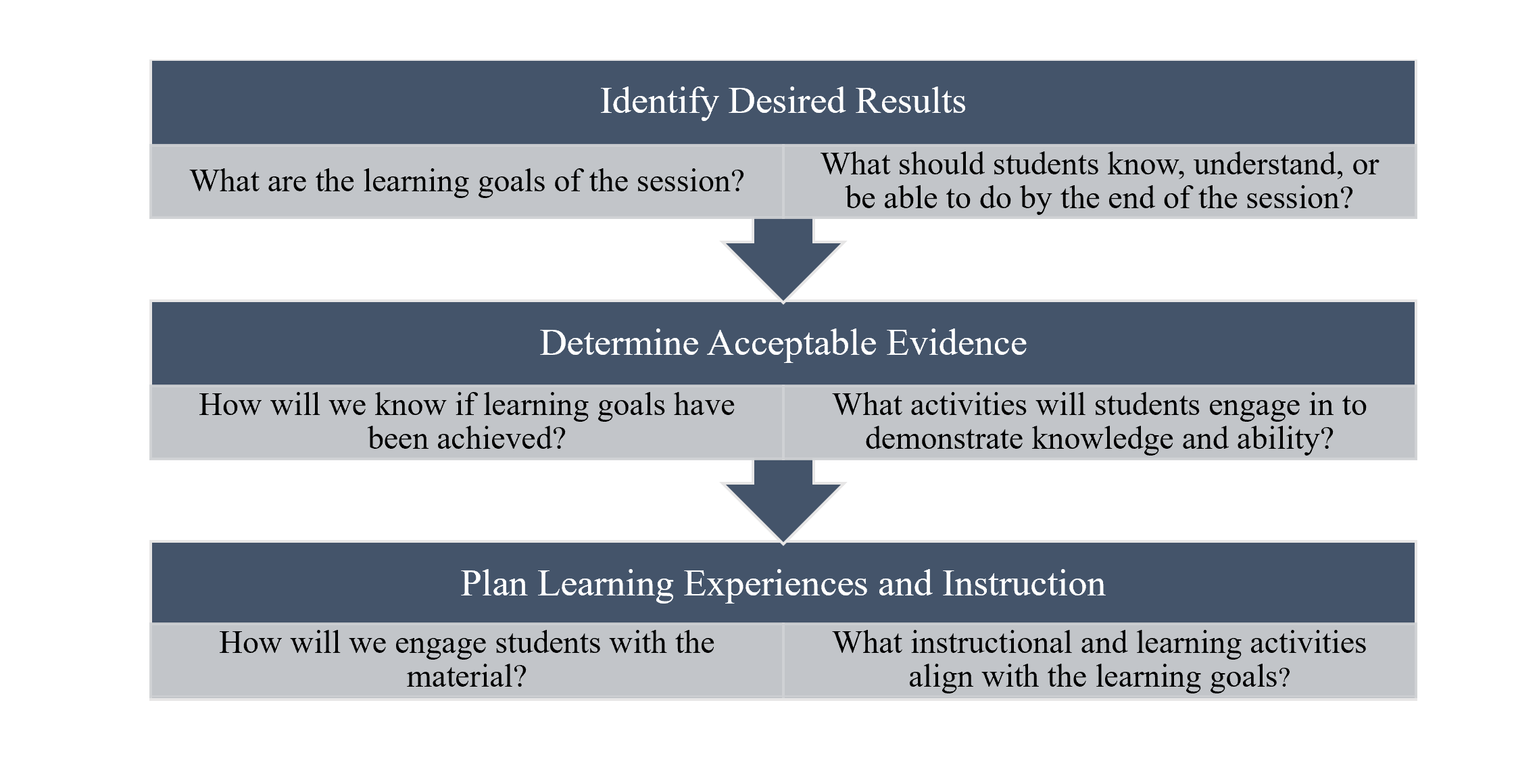

Frameworks and models can guide us in developing clear and specific learning outcomes. The most frequently used general framework is Bloom’s Taxonomy, which presents six levels of learning: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create. Each level encompasses a set of skills and abilities that reflects learning at that level:

- Remember: Learners can recall facts and concepts.

- Understand: Learners can explain ideas and concepts in their own words.

- Apply: Learners can transfer information and skills to use in new contexts.

- Analyze: Learners can synthesize information, identify patterns, and draw conclusions.

- Evaluate: Learners can assess arguments, and choose and justify a position.

- Create: Learners can use what they have learned to produce new ideas and original work.

These areas of learning are hierarchical: remembering, understanding, and applying represent lower-order thinking skills, while analyzing, evaluating, and creating are considered higher order. These levels of learning are often depicted as a pyramid, as in Figure 8.2. The original taxonomy, created by Bloom et al. in 1956, identified evaluation as the highest-level skill followed by creation, but a 2001 revision by Anderson and Krathwohl flips these two, making creation the highest-order skill. Because deeper knowledge and understanding are reflected in the higher-order levels, instructors are generally encouraged to focus on those levels when writing outcomes. Nevertheless, arguments can be made that, since the levels are hierarchical, students might need to develop the lower-order skills before they can progress to the higher orders. The key is for instructors to focus the outcomes on levels that are appropriate to the audience.

Figure 8.2: Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning

Instructors can use this framework as a starting point to write clear and specific outcomes that indicate how students will demonstrate their learning. The hierarchy can help us think about and identify appropriate levels of learning for our audience, and also suggest the sort of action verbs we could use to describe our outcomes. We can brainstorm synonyms for each level. For instance, “remember” is associated with verbs like “recall,” “list,” and “state.” Verbs associated with “understand” include “explain,” “discuss,” and “describe”; verbs for “analyze” might include “examine,” “compare and contrast,” and “critique,” and so on. You can find many lists of verbs arranged by the levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy online. See Activity 8.2 for a brief exercise in writing learning outcomes using Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Activity 8.2: Writing Learning Outcomes with Bloom’s Taxonomy

Below is a list of brief scenarios describing an information setting, audience, and library instruction content area. Choose one of the scenarios and write two to three learning outcomes for an instruction session appropriate for that scenario. Use Bloom’s Taxonomy from Figure 8.2 as a guide for thinking about learning levels and brainstorming action verbs.

- Older adults at a public library want to find quality health information.

- High school seniors have to find at least two scholarly articles to include in a research paper.

- History undergraduates are expected to incorporate primary sources into their project on civil rights.

- Adults want guidance on finding and applying for jobs online.

- Health-care professionals need to find clinical trials and research reports for evidence-based practice.

If possible, share your answers with a classmate and critique each other’s outcomes:

- Are the outcomes clear and precise? Is it obvious what learners are expected to know, understand, or be able to do by the end of the session?

- Are the levels of learning appropriate for the intended audience?

- Do the action verbs for each outcome align with the intended level of learning?

While Bloom’s is by far the most commonly used taxonomy for learning, it is not the only one. University College Dublin (O’Neill & Murphy, 2010) offers a guide to additional taxonomies, including Krathwohl’s Taxonomy of the Affective Domain (Krathwohl et al., 1964), which incorporates attention to learners’ values and attitudes, and Fink’s (2013) Taxonomy of Significant Learning, which incorporates humanistic elements of caring and learning about one’s self and others. These taxonomies can be helpful in adopting a critical approach to teaching by encouraging learners to consider the impact of what they learn beyond themselves and the classroom, and Fink suggests the taxonomies can be motivating to students as well.

Affective aspects like caring might not appear to be relevant to the kinds of content we typically teach in information settings, but if we dig deeper, we can find connections. For example, when teaching citation styles, we usually focus on the fact that if students plagiarize, they are in violation of the honor code and might receive a failing grade; however, we could recast that lesson around the idea that citation is a way of acknowledging other’s work and its influence on us. We could ask learners to think about how they would feel if a fellow student got a good grade or won an award by using their work without giving them credit. Examples like this would bring a human dimension to an otherwise dry and off-putting topic and might help students understand the purpose of citations and thus care more about the practice than they would otherwise. When developing outcomes, the specific taxonomy we use to guide us is less important than carefully describing the goal of the learning.

Making Outcomes Relevant and Meaningful

As noted earlier, many instructors feel pressured to cover enormous amounts of content. The issue for many of us is not identifying content related to our outcomes but narrowing that content down to fit our time frame and audience. The Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (ACRL, 2016) and the American Association of School Librarians’ Standards Framework (AASL, 2017) serve as good examples. The ACRL Framework consists of six frames, each of which is accompanied by four or more knowledge indicators, and four or more dispositions. The AASL Standards Framework includes six shared foundations that together include more than five dozen competencies. Needless to say, either of these frameworks would require full courses, if not entire programs, to address fully. Yet, most library instructors are limited to one-shot sessions. How can we make the most of the time we have?

Big Ideas and Enduring Understandings

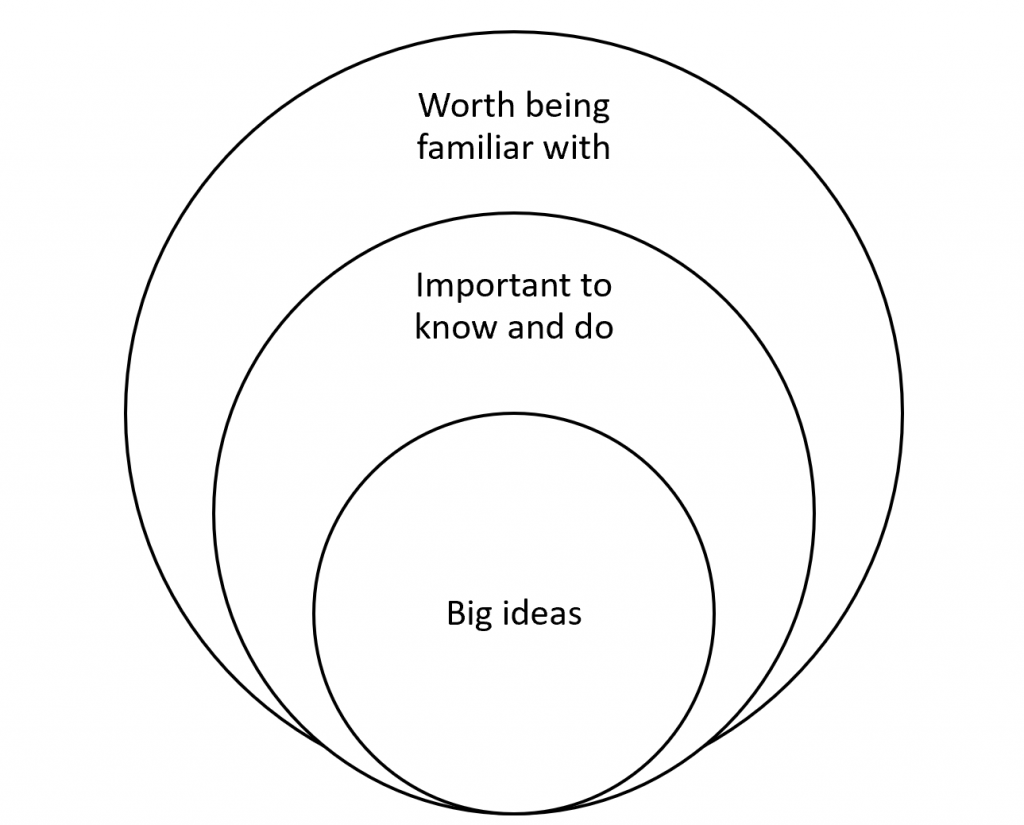

Wiggins and McTighe (2005) encourage instructors to narrow down content and prioritize learning by focusing on big ideas and enduring understandings. Big ideas are the core knowledge and skills within a discipline or content area that lead to enduring understandings, or deep learning. These ideas and understandings go beyond recall of basic facts or replication of tasks and processes and form the foundation of knowledge and skill essential to success in a discipline or content area (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Importantly, Wiggins and McTighe acknowledge that a big idea is not necessarily “big” in the sense of size or scope, but that it must “have pedagogical power … a big idea is not just another fact or a vague abstraction but a conceptual tool for sharpening thinking, connecting discrepant pieces of knowledge, and equipping learners for transferable applications” (2005, p. 70).

At the same time, certain knowledge and skills, or basic ideas, are necessary to attain the enduring understandings implied in the big ideas. In other words, big ideas are broad, conceptual understandings, while basic ideas are the building blocks upon which big ideas rest. Wiggins and McTighe (2005, p. 67) offer a few examples of the relationship between basic and big ideas from several disciplines, as shown in Table 8.4.

Table 8.4: Examples of Basic and Big Ideas

| Basic Idea | Big Idea |

| Ecosystem | Natural selection |

| Graph | “Best fit” curve of the data |

| Story | Meaning as projected onto a story |

Table 8.5 shows examples of basic and big ideas as they might apply to information literacy.

Table 8.5: Examples of Basic and Big Ideas for Information Literacy

| Basic Idea | Big Idea |

| Authority | Credible sources |

| Dewey Decimal System | Organization of information |

| Citing sources | Ethical and legal use of information |

Once we know which big ideas will underpin our instruction, we must identify the basic knowledge and skills, necessary to attain these big ideas. For example, in order to efficiently and effectively access information, learners need to grasp how libraries, indexes, and search engines organize information. Students need to understand the structures and classification systems that are used, and they must be able to implement appropriate search strategies to retrieve relevant information from those systems. In this case, a basic understanding of library classification systems like the Dewey Decimal System, an ability to differentiate between keyword and subject headings, and the ability to use limiters to search the catalog can lead to understanding the big idea of organization of information.

Beyond the big ideas and enduring understandings that are contextualized by necessary knowledge and skills are the things that are “worth being familiar with” but are not absolutely necessary. Information that is worth knowing, but not essential, could include technical jargon or key figures from history. For example, knowledge of the Dewey Decimal System (basic idea) is a stepping stone to understanding organization of information (big idea), but students learning to navigate classification systems do not need to know the name Melvil Dewey. Similarly, patrons do not need to know the term OPAC in order to learn how to search the catalog. This prioritization of knowledge and skills can be visualized, as in Figure 8.3. See Activity 8.3 for an exercise on writing learning outcomes based on big ideas and enduring understandings.

Figure 8.3: Enduring Understandings

Activity 8.3: Writing Learning Outcomes Based on Big Ideas

In this activity, you will draw on the concepts of big ideas and enduring understandings to identify essential knowledge and skills for a library instruction session, and develop relevant learning outcomes. Begin by choosing one of the following scenarios:

- Finding reliable health information for older adults at a public library

- Providing an orientation to the library for first-generation students at an academic library

- Finding information for a biographical report for elementary school students

- Finding research articles for a thesis project for college seniors

- Avoiding plagiarism and citing sources for high school students

- Beginning genealogical research for adults at a public library or archive

Instructions:

- Brainstorm the topics, ideas, and concepts you might want to address in the session. At this point, include anything that seems relevant.

- Prioritize the list, using the big ideas and enduring understandings model from Figure 8.3. Which items on the list might represent big ideas? Which are essential knowledge or skills necessary to understand those big ideas? Which are just “nice to know”?

- Write two to three learning outcomes for your instruction session, drawing on the essential skills and knowledge you have identified. Assume you have one hour for your session. Keep your audience and setting in mind.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion:

- How did you decide what was essential and what was just “nice to know”? What role did audience and setting play in making those decisions?

- Were you able to address all of the essential skills and knowledge in two to three learning outcomes? If not, how did you decide what to include and what to leave out?

- If you had 90 minutes for your session, what learning outcomes would you add, and why?

Essential Questions

Another way to identify big ideas and enduring understandings is to frame content around essential questions or questions that help contextualize the big ideas (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). As with big ideas, essential questions are usually overarching and conceptual, but they do not have to be very broad in scope. The point of essential questions is to provoke students to think more deeply about the content, and to see how the content relates to the larger world. Typically, essential questions move beyond the specific content of the lesson to more universal ideas. For example, history or civics lessons on the development of the U.S. Constitution could be framed around broader questions about whether democracy is a preferable form of government (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

We can discover essential questions within big ideas by examining content and standards documents like the ACRL (2016) Framework or AASL (2017) Standards Framework, and asking ourselves questions such as why study this topic, what larger concepts and issues underlie this topic, and how does this topic apply to the larger world. Once we have identified the essential questions, they can help us make the broader relevance of the topic more explicit for learners. Table 8.6 provides examples of essential questions related to library instruction, and Activity 8.4 is a brief exercise for developing essential questions.

Table 8.6: Examples of Essential Questions for Library Instruction

| Basic Ideas and Standards | Essential Questions |

| Search strategies (Boolean, truncation, quotes, etc.) | What does research look like? How do we do research? Why do we do research? How do you know when you are “done” searching? |

| Evaluating information (authority, currency, sources, etc.) | How do we know when information is credible? Should we care about the spread of disinformation? How do we deal with conflicting information? |

| Information has value (ACRL, 2016) | What kind of value does information have? How does the value of information impact access? Should access to information be a human right? How could we ensure that? |

Activity 8.4: Developing Essential Questions

As noted, we can often develop essential questions by extrapolating from standards and frameworks. Following are a few basic ideas and standards. What essential questions can you derive from these examples?

- Information creation as a process (ACRL, 2016)

- Using evidence to investigate questions (AASL, 2017)

- Classification systems

- Citation styles

Conclusion

Learning outcomes provide us with a destination for our instruction sessions and allow us to construct the road map that will help students arrive at those outcomes. Once we have identified learning outcomes, the content, learning activities, and instructional strategies become more readily apparent. Building on our learning outcomes, we can determine what evidence students can produce to demonstrate their learning so we can assess progress toward the learning goals. Arguably, identifying learning outcomes is one of the, if not the, most important steps in instructional design. Yet, too often, instructors never clearly and explicitly define those outcomes, or they try to retrofit outcomes onto an existing curriculum, whether appropriate or not. Backward Design challenges us to shift our approach to instructional planning so that we begin with the learning outcomes and work backward from there to assessment and content. Several best practices can help us develop clear, precise, and meaningful learning outcomes:

- Focus on the knowledge and skills that learners should develop through the instruction.

- Use action verbs to indicate in precise language the actions, habits of mind, or skills that demonstrate achievement of those outcomes.

- Draw on Bloom’s Taxonomy or other relevant taxonomies to determine the appropriate level of learning and to find verbs to convey the actions relevant to that level.

- Focus content on big ideas, enduring understandings, and essential questions to get at core knowledge and help students see how to transfer learning to new contexts.

Suggested Readings

American Association of School Librarians. (n.d.). Standards Crosswalks. https://standards.aasl.org/project/crosswalks/

AASL offers a set of handouts mapping the AASL Standards Frameworks to various curricular standards, such as the Next Generation Science Standards. These crosswalks provide a guide for developing relevant learning outcomes for school librarians.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revisions of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

This revised version of Bloom’s original taxonomy provides clear guidance and useful examples for writing learning outcomes. The text includes a number of templates and worksheets to help instructors create outcomes that are clear and measurable.

ASCD. (2019). Understanding by design. http://www.ascd.org/research-a-topic/understanding-by-design-resources.aspx

The publisher of Wiggins and McTighe’s handbook provides a number of free resources that explain and help instructors implement Backward Design. A PDF guide offers a solid overview of the Understanding by Design Framework, including a description of each of the three stages and information on developing essential questions. The site also features free articles and webinars on various aspects of Backward Design.

Fink, L. D. (2003). A self-directed guide to designing courses for significant learning. https://www.deefinkandassociates.com/GuidetoCourseDesignAug05.pdf

The author of Creating significant learning experiences developed this open access resource that offers a concise but thorough overview of his unique approach to creating significant learning. The text offers a brief overview of Backward Design and guides instructors through the process of writing learning outcomes, with a focus on aspects of significant learning experiences. Although the resource is geared toward course development, most of the advice could be adapted for workshops and one-shot sessions.

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences. Jossey-Bass.

For those looking to move beyond Bloom’s Taxonomy, this handbook guides instructors through the process of instructional design with a focus on Fink’s unique approach to creating significant learning. In addition to a focus on more traditional learning areas such as foundational knowledge and application, Fink encourages instructors to integrate outcomes related to caring and human dimensions of learning. Fink argues that these areas of focus can help students care more about a topic, which will motivate them to continue learning.

Hosier, A. (2017). Creating learning outcomes from threshold concepts for information literacy instruction. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 24(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2017.1246396

The author provides useful guidance on translating the ACRL Framework into learning outcomes, using threshold concepts as a lens.

O’Neill, G., & Murphy, F. (2010). Assessment: Guide to taxonomies of learning. University College Dublin Teaching and Learning. http://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/ucdtla0034.pdf

A clear and concise guide to Bloom’s and other taxonomies of learning. The authors provide a succinct description of each taxonomy, accompanied by a chart outlining its characteristics and sample action verbs. This is a useful guide for writing clear and meaningful learning outcomes.

Wessinger, G. (2018). Working backward to move forward: Backward design in the public library. In C.H. Rawsen (Ed.), Instruction and pedagogy for youth in public libraries (pp. 37-66). UNC Chapel Hill. http://publiclibraryinstruction.web.unc.edu/files/2018/10/instruction_for_youth_color_website-1.pdf

Part of an open access publication, this chapter explains how to apply Backward Design principles to public library instruction sessions. Throughout the book, readers will find useful pedagogical advice contextualized for public libraries.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. ASCD.

The official handbook of Backward Design, this text provides a comprehensive overview of Wiggins and McTighe’s approach to instructional design. The book is clearly written and includes numerous figures, templates, and worksheets to assist the instructor in course planning. Some materials are available for free from the ASCD publisher website listed earlier.

Ziegenfuss, D. H., & LeMire, S. (2019). Backward design: A must-have library instructional design strategy for your pedagogical and teaching toolbox. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 59(2), 307–112. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.59.2.7275

Drawing on a variation of Backward Design from L.D. Fink (cited earlier), this article provides useful advice on developing meaningful and relevant learning outcomes. The “dream exercise” is particularly powerful for envisioning long-term goals.

References

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

American Association of School Librarians. (2017). Standards framework for learners. https://standards.aasl.org/

Association of College & Research Libraries. (2016). Framework for information literacy for higher education. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Bloom, H. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals; Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. Longman.

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hosseini, H., Chalak, A., & Biria, R. (2019). Impact of backward design on improving Iranian learners’ writing ability: Teachers’ practices and beliefs. International Journal of Instruction, 12(2), 33-50. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2019.1223a

Krathwohl, D. R., Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook II: Affective Domain. David McKay Co.

Maki, P. (2010). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. Stylus.

O’Neill, G., & Murphy, F. (2010). Assessment: Guide to taxonomies of learning. University College Dublin Teaching and Learning. http://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/ucdtla0034.pdf

Shah, V., Kumar, A., & Smart, K. (2018). Moving forward by looking backward: Embracing pedagogical principles to develop an innovative MSIS program. Journal of Information Systems Education, 29(3), 139-156. http://jise.org/Volume29/n3/JISEv29n3p139.html

Shaker, G. G., & Nathan, S. K. (2018). Teaching about celebrity and philanthropy: A case study of backward course design. Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership, 8(4), 403-421. https://doi.org/10.18666/JNEL-2018-V8-I4-9233

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. ASCD.

Yurtseven, N., & Altun, S. (2017). Understanding by design (UbD) in EFL teaching: Teachers’ professional development and students’ achievement. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 17(2), 437-461. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2017.2.0226