7 Identifying Audience Needs

Introduction

Understanding our audience, their interests, needs, and information behaviors, is an important part of instructional planning. The more we know about our learners, the better we can tailor our instruction to meet their interests and needs. We would not plan a session on job hunting or retirement planning for an audience of middle school students, but we might try to link a library session to a classroom lesson on the life cycle of a frog. Likewise, we know that older adults in a public library setting are unlikely to be writing a research paper or worrying about citing sources for that paper, but they might be interested in learning about health or financial-planning resources.

McTighe and O’Connor (2005, p. 14) remind us that “diagnostic assessment is as important to teaching as a physical exam is to prescribing an appropriate medical regimen.” Before any instruction session, we should ask ourselves: “Who will be in my audience?” “What sorts of topics are they interested in?” What interests them about those topics?” “What do they already know?” and “What do they want to learn?” But how do we discover this information about our learners? Answering these questions can be especially challenging for librarians outside of the K-12 school system. School librarians have some advantages in getting to know their students. They are typically working within a curriculum framework, whether set by the state, district, or school, that broadly indicates the level of knowledge students should have across various subjects at each grade level. Also, school librarians have an entire year with each class; therefore, they have time to get to know the students as a group and individually, and make incremental adjustments to their instruction as they learn more about their students’ knowledge and abilities.

Most other librarians rely on the “one-shot” instruction session, or workshop model, in which they meet with the specific audience as a group only once and often for a relatively short time period. Typically, we will not have an opportunity to communicate with the audience prior to the session, giving us little time to learn about our students. Yet, even with a one-shot session, techniques exist to help us gather information about our audience. The rest of this chapter provides an overview of those techniques, beginning with broad approaches to learning about communities and moving to more specialized methods to learn about individual students and groups. See Activity 7.1 for a brief exercise on audience assessment.

Activity 7.1: Learning About Audiences

Before reading the rest of this chapter, take a moment to reflect on the concept of audience assessment by answering the following questions. If possible, keep track of your answers so you can come back to them at the end of the chapter.

Begin by choosing an information setting such as an archive or a public, academic, or corporate library, and think about a specific population with whom you might work, such as elementary school children, lawyers, graduate students, or older adults. As you answer the following questions, try to frame your answers in terms of that setting and patron group.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion:

- What are some ways you could learn more about your audience’s instructional needs, interests, or challenges? Write down as many methods as you can think of.

- What are some existing sources of information about this audience?

- How could you use the information you gather to plan better instruction sessions?

Learning About Audiences Through Research

Research studies and reports can be an excellent way to learn about learners; these resources can provide an overview of the specific needs, challenges, and behaviors of our audience so we can plan sessions that will address those areas, and they often identify the common misunderstandings and stumbling blocks learners face (Guskey, 2018). One classic example is Kuhlthau’s (1988) research on the Information Search Process (ISP). Through a series of studies, Kuhlthau demonstrated that people undertaking a research project typically progress through seven steps:

- Initiation: Beginning to search for information

- Topic selection: Identifying a topic

- Exploration: Learning more about the selected topic

- Formulation: Narrowing the focus

- Collection: Gathering and organizing information

- Presentation: Synthesizing and sharing the information

- Assessment: Reflecting on their learning

In addition to identifying these cognitive stages, Kuhlthau (1988) uncovered the affective behaviors or feelings that researchers experience during each stage. She found that students fluctuated among feelings of doubt, confusion, uncertainty, confidence, clarity, and optimism as they progressed through the research steps. Using this research, we can plan instruction that not only targets the tasks involved in each step of the research process but also supports the students’ affective states. Kuhlthau (2004) describes “zones of intervention” in which she offers specific guidance to librarians that suppport both the cognitive and affective aspects of the information search process.

Project Information Literacy (PIL) is a wealth of research on the information behaviors of undergraduates. Through years of research, PIL has uncovered valuable insights into learners’ research processes, including common challenges and stumbling blocks. For instance, early studies revealed that college students are overwhelmed with the amount of information available to them, and that getting started on a research project is one of the most difficult steps for them (Head, 2013; Head & Eisenberg, 2009). The studies found that because undergraduates generally lack the background knowledge and specialized vocabulary of the field, they have trouble identifying and narrowing down a topic. This information could be invaluable to academic librarians. Often, these librarians start instruction sessions by discussing how to search for articles for a research paper, assuming students have already selected a topic. But this research suggests that, at least in some cases, the session might be more helpful if the librarian begins at an earlier point in the research process and guides students through the steps of gathering background information in order to develop a paper topic.

PIL also has explored the information behaviors and needs of people in the early stages of their careers, finding that recent graduates are adept at finding information, though they tend to rely on relatively simple techniques and sources, and they are less skilled at solving information problems and asking probing questions (Head, 2012). This information on workplace information literacy could be useful for special and public librarians. In addition to research reports, PIL publishes interviews with researchers and educators, video overviews of research findings, and guides to using the research; all of their publications are freely available online.

The Pew Research Center is another excellent source of information about attitudes, interests, and information concerns across a variety of relevant topics, including media, news, and technology, and its research reports also are available freely online. Pew generally focuses on the general American adult population, making its findings especially of interest to public librarians. Several of its reports have focused specifically on American adults’ attitude toward and use of public libraries. For instance, surveys found that just over 60 percent of American adults would like libraries to offer training on digital literacy topics, including how to find trustworthy information (Geiger, 2017; Horrigan & Gramlich, 2017). Other relevant reports include information on issues of health literacy, how Americans use social media, where Americans get their news, their attitudes and concerns about “fake news,” and general information seeking behaviors. Some reports focus on the concerns and behaviors of specific populations, such as older adults or teens.

Finding Relevant Research

Librarians are known for their research skills, and as instruction librarians we can put those skills to work learning about our potential audiences. As librarians or library school students, readers of this book are well versed in resources and search techniques, but this section will offer some suggestions for where and how to find information about our learners. Of course, research studies must be used judiciously. Some research studies involve small samples, lack random samples, or are otherwise limited in their generalizability. We need to evaluate the merits of any study and be cautious of overgeneralizing the findings, but these studies offer some broad insight into a community.

Within library and information science, hundreds of studies have examined how people search for, locate, access, evaluate, and use information, and have proposed models to understand these processes. Some studies describe information behaviors generally, while others look at specific populations, ranging from Spanish speakers, immigrants, and older adults to historians and scientists.

Scholarly journals and research reports are a natural starting point for evidence-based information about potential audiences. A range of LIS journals frequently publish articles on the information behaviors, needs, interests, and challenges of a wide variety of patron communities. Journals such as Library and Information Science Research and Library Quarterly publish articles about many different user groups and information settings, while other titles focus on specific settings, such as academic libraries or archives, or certain functional areas, such as reference and user services. We can search for information using terms like “information behavior” or “information needs” or terms related to specific aspects of information literacy, such as “search,” “evaluation,” and “fake news” to find related studies. We might also add audience descriptors, such as “youth,” “undergraduate,” “historian,” or “English language learner” to limit our results. Keep in mind that we can find relevant information outside of LIS literature. Discipline-specific journals and databases will offer insight into the needs and interests of different communities of practice. Fields such as education, psychology, political science, and health include studies about learning, literacy, and information behaviors as well.

In addition to the Pew Research Center and PIL mentioned earlier, several other research organizations publish reports that offer insight into our potential audiences. Editorial Projects in Education publishes Education Week along with special reports that focus on K-12 education, while Ithaka S+R publishes open access research on higher education, including a triennial report on faculty perspectives on the library. The Media Insight Project was launched to study news consumption and includes reports on the general adult population that could be of interest to public librarians. Researchers from the Stanford History Education Group published a study in which they tested the ability of over 7,000 middle school, high school and college students to evaluate online information and identify fake news (Wineburg et al., 2016). The report provides an overview of student abilities and identified specific strengths and weaknesses at each level.

Professional associations can also be good sources to learn about potential audiences, and students can often get discounted memberships in these organizations. Many professional associations publish journals, newsletters, and research reports which are usually a benefit of membership, some of which might also be available as open access publications. In addition, most professional associations run one or more conferences a year often featuring paper presentations, later published as conference proceedings. For instance, recent Association of College and Research Libraries conferences have included papers such as “1G Needs Are Student Needs: Understanding the Experiences of First-Generation Students” (Daly et al., 2019), and “Learning What They Want: Chinese Students’ Perceptions of Electronic Library Services” (Michalak & Rysavy, 2019). Each of these papers provides a research-based overview of a specific group’s needs and experiences on which other practitioners could draw. Even when they are not research-based, conference presentations might share best practices related to interacting with audiences, and alert us to the trends that are concerning our colleagues on these topics.

Most information professionals are likely to find relevant information through the American Library Association (ALA), which has a section called the Library Instruction Round Table (LIRT) devoted specifically to issues of instruction and pedagogy. LIRT publishes an annual list of the best articles related to library instruction, called the LIRT Top Twenty. Academic librarians might consider the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL), including its Instruction Section. School librarians will be interested in the American Association of School Librarians (AASL). In addition to the Public Library Association (PLA), public librarians can find interesting reports through the Urban Libraries Council. As with scholarly journals, however, we should not necessarily limit ourselves to LIS associations. For example, academic librarians might explore general higher education associations, such as the Association of American Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) and the Council of Independent Colleges (CIC), while school librarians will find relevant information through the Association of American Educators.

Assessment Through Demographics and Community Organizations

Often, we can find excellent sources of audience information in our own communities. At the broadest level, public librarians can use tools from the U.S. Census Bureau to get basic demographic information about their city or town, including a breakdown of the population by age, gender, race, education levels, income levels, languages spoken at home, and numbers of households with school-aged children. While this information is broad, it offers a helpful overview. A public library in a city with a high percentage of older adults and few families with children might plan different programming and events than a librarian in a town with a lot of young families. In planning programs, librarians might also consider what languages their patrons speak and investigate the possibility of offering interpreter services or programs in languages other than English. Many cities and towns are launching data portals that provide additional demographic information about their community beyond the national census.

Remember that census data is only a starting point. Once you have a sense of the broad demographics of your community, you can take steps to learn more specifics. For instance, once you have a sense of the number of households with children in your community, you might investigate whether the schools have libraries and whether those libraries are staffed by professional librarians; the breakdown of children attending public, charter, or private schools, or being homeschooled; and where the local preschools and child care centers are located in relation to the library branches. This information can help inform the instruction program. For instance, if libraries in the public schools are under- or unstaffed, the public library can fill a gap by developing instruction to support the curriculum and provide help to students as they complete assignments.

School and public librarians should also build relationships with community and social service organizations. Not only can these organizations help the library reach new audiences and partner with the library in providing programming and instruction, they can be additional sources of community information. Community health centers might have information on overall health literacy, common health-care questions, and information needs and concerns of the homeless, underhoused, and food-insecure populations. Immigration-support centers tend to have more detailed and current information than the census does on race, national origin, ethnicity, and languages spoken of those newly arrived to the community.

Similarly, academic librarians can work with campus offices to learn more about their students. Admissions offices should have detailed information about the general profile of admitted students, including average high school GPAs, entrance exam scores, international status, first-generation status, and so on. Academic librarians will want to pay attention to the number of nontraditional students. The definition of nontraditional students varies but typically includes learners who meet one or more of the following characteristics: they are financially independent of parents or guardians; work full time; have one or more dependents and/or are a single caregiver; did not complete high school; and/or delayed entrance to college, often taken to mean that they are age 24 or older at the time they begin college (U.S. Department of Education, 2015). Roughly 70 percent of undergraduates meet at least some of the criteria of a nontraditional student, and the added work and family responsibilities these students face can impact their instructional needs.

Academic support services, such as the writing center and tutoring services, can help the library identify general areas of concern for learners who might warrant instructional support. For instance, writing coaches might notice that students are including dubious sources in their papers, or that they have trouble properly formatting citations. Disability services should have aggregate information about the number and types of disabilities reported on campus, which can help librarians plan accessible instruction sessions, as discussed in Chapter 6. An international student office can help the library pinpoint the specific needs of learners from outside of the United States. Finally, academic departments and faculty can be key informants as to the specific needs of their majors. For instance, the history department might want their students to learn to find and use primary sources, while science students might need to access data sets.

While all of these sources of information are useful, they must be used carefully. We must take care to always respect patron privacy when gathering information. Not only is patron privacy an ethical obligation of the library field, it is also ensured by many state and federal laws such as the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), which protects student data. When working with community and campus offices to access demographic data or other information about patron needs and interests, we should be clear that we want only aggregate data, not personally identifiable information.

Pre-Assessment Techniques

While research literature and community demographics can offer valuable insight into our audiences, they tend to lack nuance and treat broad communities as if they are a monolithic or homogeneous group. We have to remember that this information provides a broad picture of a community but cannot describe any one individual. While it may be true that many older adults are interested in health information, individual needs and interests within this group could vary widely. One patron might be struggling to understand her Medicare benefits, while another might be the primary caretaker for a grandchild and need pediatric health information. A school or academic campus might have a certain number of students with a specific learning disability, but that disability could manifest differently for each student, and each student could need or prefer different accommodations or teaching approaches. We need to remember that people are intersectional; that is, they have many different parts to their identities and are not defined by any one single characteristic such as race, age, or disability status. We should use demographic and community data as a starting point that can help us understand our broad community but not to limit or pigeon-hole individual patrons. The pre-assessment techniques outlined below can help us to move beyond the general overviews available from research and community data to discover more about our specific group of learners.

Pre-assessments are a set of methods for gauging learners’ knowledge and abilities before beginning a new instruction session. For example, teachers can give students a brief quiz at the beginning of a unit to determine what they already know about the unit topic, or a librarian might poll a class to find out how many students have experience with certain databases or search strategies like Boolean operators. Because they engage directly with learners, pre-assessments can offer instructors targeted insight into a group of students’ existing knowledge about a topic and allow the instructor to adjust the lesson to meet the learners’ current needs. Pre-assessments are “a way to gather evidence of students’ readiness, interests, or learning profiles before beginning a lesson or unit and then using that evidence to plan instruction that will meet learners’ needs” (Hockett & Doubet, 2013).

Pre-assessments are commonly used to gauge students’ knowledge or abilities, including how much learners recall from past lessons, how much they know about a new topic, or how well they have mastered a certain skill. They can also act as a diagnostic tool to identify gaps in student knowledge or misconceptions about a topic. Hockett and Doubet (2013) stress that pre-assessments should not be used only to measure knowledge in the sense of recall of facts, but they should also attempt to gauge student understanding and ability. Although learners in a library classroom might be able to name the Boolean operators, they might not know how to use those operators properly to broaden or limit their searches. A good pre-assessment will uncover understanding. Otherwise, instructors might assume that students’ knowledge of facts implies their understanding and plan an instruction session for which learners are not ready.

Pre-assessments can be formal or informal, high or low stakes. Formal pre-assessments could consist of quizzes, worksheets, or performances that require students to demonstrate their knowledge, ability, and understanding. Informal pre-assessments could include a brief in-class discussion in which learners answer questions about their knowledge of a topic, or a quick poll to check knowledge of a topic. Most pre-assessments, especially in information settings, are low stakes since the goal is to understand students’ prior knowledge, rather than assess their performance.

The use of pre-assessments aligns well with the cognitivist approach to teaching as described in Chapter 3. According to cognitivist learning theory, people create knowledge by associating new information with their existing knowledge base. Pre-assessments encourage learners to recall and reflect on what they already know, which can facilitate connections to the new information introduced in the current lesson. Once we are aware of our students’ existing knowledge and experiences, we can weave those into the lesson, increasing the relevance of the material and making the connections between the new information and the existing knowledge even more explicit (Hockett and Doubet, 2013). Guskey (2018) points to rigorous research suggesting that when teachers use pre-assessments as a diagnostic tool and use the data to create lessons that address gaps in understanding and reinforce the mastery of relevant knowledge and skills, student learning increases (Leyton-Soto, 1983). Finally, when used appropriately, pre-assessments offer learners a little preview of upcoming topics and can be used to build interest and excitement. Instructors can use the pre-assessments to set expectations by indicating what students will be learning and explaining why these topics are important (Guskey, 2018; Hockett & Doubet, 2013).

While useful, pre-assessments can take up valuable instruction time. Occasionally, academic librarians might persuade an instructor to administer a pre-assessment before a library instruction session or to assign the pre-assessment as homework. A public librarian could possibly send a pre-assessment by email to workshop participants if those participants had to register for the session. Even if these options are possible, however, participants might not feel obligated or motivated to engage, resulting in few or no responses. Usually, librarians will have to use their own class time for pre-assessments, and when limited to a 45- to 60-minute one-shot session, losing even 5 or 10 minutes of instruction time can have a big impact. Thus, we need to carefully design assessments that uncover useful information with minimal use of class time.

Designing Meaningful Pre-assessments

Hockett and Doubet (2013) recommend pre-assessments start with the learning goals or outcomes of the lesson. Once we know what students should know or be able to do by the end of a lesson, we can determine what knowledge or skills they need in place to get started and then develop assessment tools to explore students’ current knowledge and abilities. Wiggins and McTighe (2005) describe this as determining where learners are coming from before focusing on where they need to go next.

Often, pre-assessments are relatively short and simple. Instructors may be tempted to collect a lot of information, but since the purpose is to guide the upcoming lesson, these assessments should focus only on content or skills that are directly relevant to that lesson. If you have only one meeting with a group of learners, it might seem like a good use of time to find out as much as you can about that group, but long and complex assessments run the risk of alienating students and generating data that is not relevant to the lesson and therefore not useful in planning. Specific examples of pre-assessment tools and strategies are offered later in this chapter.

Using Pre-assessment Data

The goal of pre-assessment is to create a better learning experience for students. The information gained through pre-assessments can guide our decision making not only “into what to teach, by knowing what skill gaps to address or by skipping material previously mastered,” but also into “how to connect the content to students’ interests and talents” (McTighe & O’Connor, 2005, p.14).

One obvious use of pre-assessment data is to guide content. Once we know what knowledge our learners lack or what abilities they have not yet mastered, we can make an informed decision about where to begin a lesson and spend time reviewing content as necessary. For instance, one of the book authors, Laura, prepared a workshop on job hunting for a public library audience. She planned to begin by demonstrating how to search for job postings but realized at the beginning of the session that many of the learners were unsure how to find a job bank in which to search, so she quickly adjusted her lesson and began with a general web search to find job banks. Hockett and Doubet (2013) provide a detailed example of a high school assessment focused on World War II. Using carefully constructed questions, the teacher identified areas students were familiar with, along with some misconceptions they held, and was able to adjust her plan accordingly.

Pre-assessments can also guide our overall approach to the classroom, including which activities we use to present content, and how we might group learners to best match their current levels of knowledge. For instance, a seventh-grade science teacher used a pre-assessment to determine each student’s level of knowledge for a lesson on the nervous system (Pendergrass, 2013/2014). Based on the results, the teacher broke students up into several groups. While students who did well on the pre-assessment worked on more advanced activities, the teacher gathered the students who were struggling with the content and spent time reviewing concepts with them. Further, she previewed content from the next lesson so these students could have extra time to begin mastering the new information.

Pre-assessments can give teachers ideas to connect with and engage their students. In the World War II example, the teacher asked students for examples, either from their own lives or from books and films, of one conflict causing another. As a result, she learned that many learners were familiar with the Hunger Games, and she was able to use themes of conflict and penalties from that series (and from other personal experiences that students provided) to connect with lesson content. The familiar examples made the lesson more engaging and facilitated student connections of new information to their existing schema.

Some pre-assessments also surface worries, frustrations, or lack of confidence on the part of learners, which can help the instructor create a supportive and empathetic environment. For instance, a group of college undergraduates discussing an upcoming research paper might reveal that they feel pressured to get the work done on time or are not confident in their ability to find good information. The library instructor could use this information to emphasize time-saving techniques, to reassure learners about their concerns, and to provide positive and encouraging feedback when they are successful in their searching.

Pre-Assessment Examples

Dozens of pre-assessment tools and ideas exist. In fact, many of the active learning techniques described in Chapter 4 could double as pre-assessment tools. The main requirement of a pre-assessment is that it gathers data about what students already know, understand, and are able to do. This section provides a few examples of pre-assessment tools, with an emphasis on informal, low-stakes, and relatively quick methods that are most likely to be useful in a library classroom.

K-W-L

One popular pre-assessment is the K-W-L, which stands for know, want to learn, and learned (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). The instructor begins by asking learners to reflect on what they already know (or believe they know) about a topic. The students could work individually or together to brainstorm their thoughts, showing the instructor their current knowledge and revealing any gaps or misunderstandings.

In the next step, the instructor asks students what they want to learn about the topic, which might be presented in the form of questions they have. This step helps the learners begin to engage with the topic and can build some excitement about what is to come. The instructor can also use this step to link the students’ interests and questions to the learning goals of the lesson. Throughout the lesson and at the end of the instruction, the teacher asks the students to reflect on what they are learning. This step helps the students (and instructor) track progress toward learning goals and encourages the kind of reflection and recall that can deepen learning. Although the K-W-L method is often associated with younger children, as in the example provided by Pattee (2008), it works equally well with older children and adults. Example 7.1 provides a sample K-W-L worksheet, while Activity 7.2 offers an opportunity to use the K-W-L worksheet to plan instruction.

Example 7.1: K-W-L Worksheet

| What You Know | What You Want to Learn | What You Learned |

| People need to eat more vegetables. | Are vegetarians healthier than other people?

Which vegetables are the healthiest? |

|

| Calcium is an important nutrient. | Does drinking milk make you grow taller? | |

| People should eat foods high in fiber and whole grains. | Which foods have high fiber? |

Activity 7.2: Using a K-W-L Worksheet to Plan Instruction

In the K-W-L chart shown in Example 7.1, middle school students worked in groups to identify what they know and what they want to learn about nutrition. Next, the librarian will help them research the answers to what they want to learn. After the lesson, students will reflect on what they have learned and fill in the rest of the chart.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion:

- What does the information on this chart reveal about learner knowledge of the topic?

- Where do you see strengths in the students’ knowledge, and where do you see gaps or misconceptions?

- How could a library instructor use this chart to plan an instruction session? What topics, activities, or resources might the lesson cover, and why?

Worksheets

Library instructors can use worksheets to probe student knowledge and understanding of a topic. In developing questions or tasks for a worksheet, we should focus on recall, reflection, and potential for learning. See Activity 7.3 for an excerpt of a sample library worksheet and reflection questions.

Activity 7.3: Using a Pre-assessment Worksheet

The following pre-assessment worksheet could be used to gauge undergraduates’ understanding of search strategies prior to a library instruction session.

Questions for Reflection and Discussion:

- What would a library instructor learn about knowledge levels or gaps from student answers to these questions?

- How might a library instructor use the information from this worksheet to plan a lesson?

LIBRARY 101 WORKSHEET

- Conduct the following searches in Library Catalog:

- Type in each of these searches exactly as written and record the number of results for each search:

- libraries and children

- libraries or children

- libraries not children

- librar* and child*

- Do the same for the following searches:

- social media

- social not media

- “social media”

- Type in each of these searches exactly as written and record the number of results for each search:

- Why do you think each search returns a different number of results? How do the “ands,” “ors,” “nots,” asterisks, and quotation marks work to change the search?

- Now, imagine you wanted to do a search on how libraries are helping children learn about and use social media. What would be the best way to write out that search?

Brainstorm

Instructors could use brainstorming activities to encourage learners to write down anything they know about a topic prior to beginning a new lesson. Students might work individually or in groups to pool their knowledge.

Concept Map

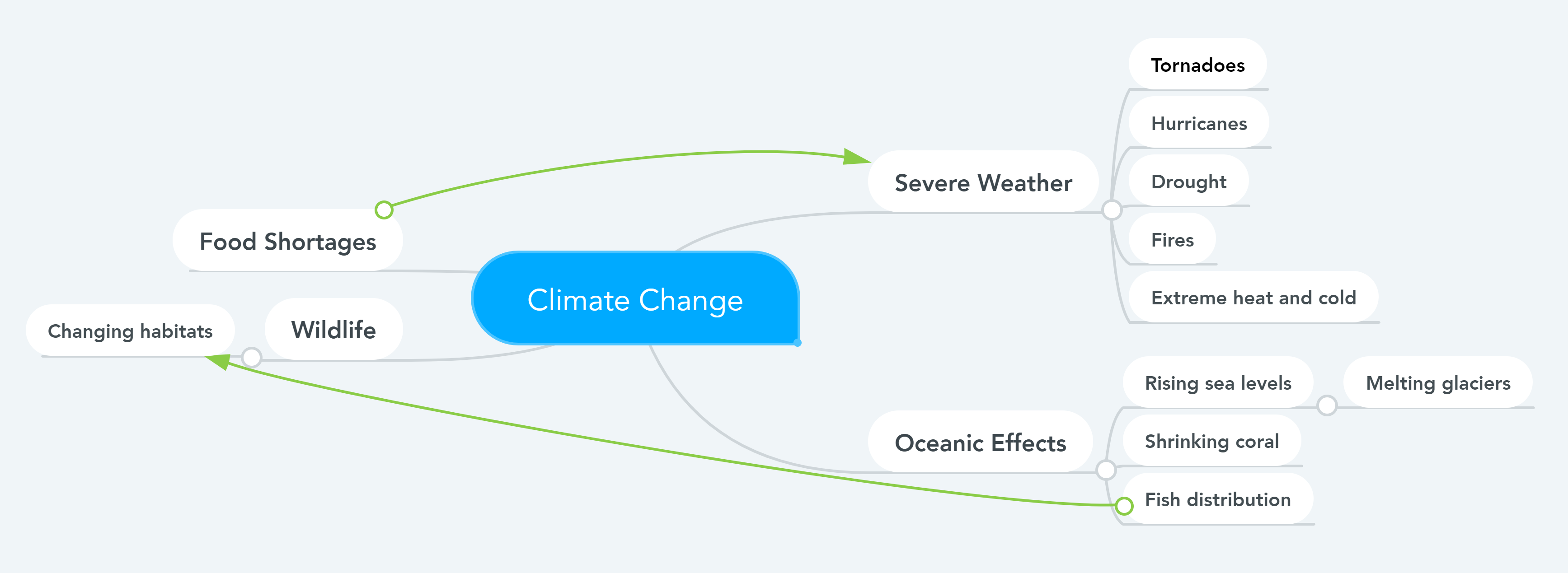

Like a brainstorm, concept maps ask learners to identify as many relevant aspects or subtopics of a concept as they can but also to show the various connections between and among the topics. Instructors could probe student understanding by asking them to explain the connections. Figure 7.1 shows a sample concept map created by using a free version of MindMeister.

Figure 7.1: Climate Change Concept Map

Polls

Polls are a relatively simple and quick way to get a broad sense of the knowledge level of the class. Poll questions could be content questions with right and wrong answers, self-perception questions which ask learners to indicate what they know about a topic, or even affective questions asking students, for instance, if they are excited or nervous about a topic. Some examples of polling questions include:

- Have you ever downloaded an app before?

- Have you ever used Google Scholar before?

- Do you feel confident that you can identify “fake news”?

- If you want to search for a phrase in a library database, what symbol should you use:

- Quotation marks

- Asterisk

- Question mark

- Which of these is NOT a sign of a scholarly article:

- List of references

- Authors with special credentials or affiliations to research institutions

- Charts and graphs

- Colorful pictures

We can use polling software or a simple show of hands to answer questions. One advantage of polling software is that it is usually anonymous, which might allow learners to be more honest in their answers. In addition, electronic polls might offer an option for multiple-choice answers, which can allow instructors to be more specific. Some of the products, like Poll Everywhere and AnswerGarden, allow for open-ended questions and can even display answers as a word cloud. Gewirtz (2012) gives an overview of polling in the library classroom. Although her article focuses on Poll Everywhere, her general advice could be applied to other polling products, and her guidance on questions is relevant even for polling the class without software. Keep in mind that even if the polling software itself is free, students need access to a device such as a smartphone or tablet to enter their answers. Activity 7.4 provides an opportunity to develop some of your own polling questions.

Activity 7:4: Developing Polling Questions

Polling the class is a quick and easy way to get a sense of student knowledge before beginning a lesson. We can ask learners to answer poll questions by raising their hands, or we can use polling products like Poll Everywhere to gather answers electronically.

Imagine that you are preparing a library instruction session for one of the scenarios below. Try to think of two or three poll questions you could ask your learners as a pre-assessment before beginning the lesson.

- A voter registration session for young adults at a public library or high school

- A session for political science majors writing a paper exploring the impact of disinformation campaigns on elections in the 21st century

- A health literacy session in a public library for older adults with chronic health issues

- A workshop for company staff on using the new Bloomberg terminal

Analyzing Pre-Assessment Data

Because we often administer pre-assessments at the start of the class, we will need to analyze the data very quickly if we are going to use it to tweak that session. The first step is to recognize how much time different tools entail, both for the learners to complete and for us to analyze the results, and to choose a tool appropriate to the audience, venue, and time frame. In general, open-ended pre-assessments, like concept maps, brainstorms, and K-W-Ls, will take longer to analyze because we have to look for patterns in the learners’ written responses. However, even with limited time we can use these tools if the group is relatively small. An experienced instructor can read through 10 or 15 concept maps or K-W-L charts and identify issues in a matter of minutes. With large groups or shorter time frames, we can limit ourselves to a quick show of hands or use worksheets or polls with close-ended or multiple-choice questions to speed the analysis. In such cases, we can skim through the answers quickly to identify common mistakes or issues to address. While challenging, we can make sense of the information quickly and decide how to use it in real time, and the analysis and decision making get easier with experience.

Conclusion

The purpose of library instruction is to help students and patrons gain the skills and knowledge they need to be successful in their information endeavors, whether that endeavor is completing a research paper, understanding their health-care options, or finding a new job. Since patron needs are at the heart of our instruction, any lesson plan should begin with steps to better understand the needs, interests, and prior knowledge of those patrons so that we can develop instruction that best suits those needs.

When gathering information about learners, keep the following points in mind:

- Pre-assessments help us understand our learners by gauging their current levels of knowledge and understanding on a topic. With this information, we can meet students where they are and plan a lesson that builds on that knowledge and understanding.

- A wide variety of pre-assessment tools exist, including worksheets, concept maps, polling, K-W-L sheets, and brainstorms. Many active learning techniques can double as pre-assessments.

- Research literature and community organizations can give us an overview of our broader community, and what the needs and interests of various groups might be.

- While research and demographics are useful, we must remember that these broad overviews do not apply to every individual within a group. Ideally, librarians will use research literature and community demographics to develop that broad picture of the community, and then implement pre-assessments in class to pinpoint the knowledge levels of that particular group of students.

See Activity 7.5 for a final activity on pre-assessments.

Activity 7.5: Reflecting on Pre-assessments

Jot down your answers to the following questions (you might recognize these questions from Activity 7.1. Try to answer them again here without your notes).

- What are some ways that librarians could learn more about their audience’s instructional needs, interests, or challenges? Write down as many methods as you can think of.

- What are some existing sources of information about our audiences? You might choose a particular audience and focus on sources relevant to them.

- How can librarians use the information they gather to plan better instruction sessions?

- How confident do you feel about your ability to learn about the audiences you’ll have in your classrooms?

Now, return to your answers to these questions from Activity 7.1.

- Have your answers to any of these questions changed from the first time you answered them? If so, how?

- Were there any gaps in your initial answers to the questions that were addressed in your final answers?

- Do your answers to the second round of questions suggest any change of knowledge or understanding after reading the chapter?

Suggested Readings

Brooks, A. (2013). Maximizing one-shot impact: Using pre-test responses in the information literacy classroom. The Southeastern Librarian, 61(1), 41-43. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/seln/vol61/iss1/6

This brief article provides a library-specific look at implementing a pre-test to learn about the audience for a one-shot academic library instruction session. It outlines the reasons for using a pre-test, the design of the test, and how to use the test responses to guide instruction. Although the author uses the word “test,” the method used is actually low stakes and more like a survey.

Campbell, M. L., & Campbell, B. (2008). Mindful learning: 101 proven strategies for student and teacher success. SAGE. https://www.corwin.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/25914_081222_Campbell_Ch1_excerpt.pdf

Chapter 1 of this book is devoted to prior learning. The authors give a solid, research-based overview of the need to assess prior learning, followed by several examples of assessment techniques. The text includes helpful graphics and templates.

Curtis, J.A. (2019). Teaching adult learners: A guide for public librarians. Libraries Unlimited.

Curtis provides a clear introduction to andragogy to contextualize instruction in public libraries. She also addresses issues of culture and generational differences in teaching adults. Covering many aspects of instruction, including developing learning objects and teaching online, this book is valuable as one of the few to focus exclusively on issues of teaching and learning in public libraries.

Hockett, J. A., & Doubet, K. J. (2013). Turning on the lights: What pre-assessments can do. Educational Leadership, 71(4), 50–54. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational_leadership/dec13/vol71/num04/Turning_on_the_Lights@_What_Pre-Assessments_Can_Do.aspx

This article gives a concise overview of pre-assessments along with some clear, real-life examples of how they have been used. The authors also offer useful guidance on designing your own pre-assessment

Lutzke, A. (n.d.). Library programs: What brings ’em in the doors? Humanities Booyah. https://www.wisconsinhumanities.org/library-programs-what-brings-em-in-the-doors/

In this blog post, a public librarian shares her methods for learning what interests her audiences. She discusses reaching out to community groups, talking to patrons, and conducting surveys. Although the ideas are not discussed in depth, this post is a good starting point for ideas.

Project Information Literacy. (n.d.) https://www.projectinfolit.org/

This website is a wealth of research reports, videos, and other materials focused on the information behaviors of college undergraduates and recent graduates. This information can guide academic librarians as they plan instruction sessions. All materials are freely available.

References

Daly, E., Hartsell-Gundy, A., Chapman, J., & Yang, B. (2019). 1G needs are student needs: Understanding the experiences of first-generation students. In D. Mueller (Ed.), ACRL 2019: Recasting the Narrative (pp. 149-162). Association of College & Research Libraries. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2019/1GNeedsAreStudentNeeds.pdf

Editorial projects in education. https://www.edweek.org/info/about/index.html

Education week. 1981-. Editorial projects in education. https://www.edweek.org/ew/index.html?intc=main-topnav

Geiger, A. W. (2017). Most Americans—especially Millennials—say libraries can help them find reliable, trustworthy information. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/08/30/most-americans-especially-millennials-say-libraries-can-help-them-find-reliable-trustworthy-information/

Gerwitz, S. (2012). Make your library instruction interactive with Poll Everywhere: An alternative to audience response systems. College & Research Libraries News, 73(7). https://crln.acrl.org/index.php/crlnews/article/view/8793/9374

Guskey, T. R. (2018). Does pre-assessment work? Educators must understand the purpose, form, and content of pre-assessments to reap their potential benefits. Educational Leadership, 75(5), 52–57. http://tguskey.com/wp-content/uploads/EL-18-Pre-Assessments.pdf

Head, A. J. (2012). How college graduates solve information problems once they join the workplace. Project Information Literacy. https://www.projectinfolit.org/uploads/2/7/5/4/27541717/pil_fall2012_workplacestudy_fullreport.pdf

Head, A. J. (2013). How freshmen conduct research once they enter college. Project Information Literacy. https://www.projectinfolit.org/uploads/2/7/5/4/27541717/pil_2013_freshmenstudy_fullreportv2.pdf

Head, A. J., & Eisenberg, M. B. (2009). Finding context: What today’s college students say about conducting research in the digital age. Project Information Literacy. https://www.projectinfolit.org/uploads/2/7/5/4/27541717/2009_final_report.pdf

Hockett, J. A., & Doubet, K. J. (2013). Turning on the lights: What pre-assessments can do. Educational Leadership, 71(4), 50–54. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational_leadership/dec13/vol71/num04/Turning_on_the_Lights@_What_Pre-Assessments_Can_Do.aspx

Horrigan, J. B., & Gramlich, J. (2017). Many Americans, especially blacks and Hispanics, are hungry for help as they sort through information. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/11/29/many-americans-especially-blacks-and-hispanics-are-hungry-for-help-as-they-sort-through-information/

Ithaka S+R. (n.d.). https://sr.ithaka.org/

Kuhlthau, C. C. (1988). Longitudinal case studies of the information search process of users in libraries. Library and Information Science Research,10(3), 257-304.

Kuhlthau, C. C. (2004). Seeking meaning: A process approach to library and information services. Libraries Unlimited.

Leyton-Soto, F. (1983). The extent to which group instruction supplemented by mastery of initial cognitive prerequisites approximates the learning effectiveness of one-to-one tutorial methods [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Chicago.

Library and information science research. 1987-. Elsevier. https://www.journals.elsevier.com/library-and-information-science-research

Library Instruction Round Table. (2019). LIRT top twenty. http://www.ala.org/rt/lirt/top-twenty

Library Quarterly. 1931-. University of Chicago Press. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/journals/lq/about

McTighe, J., & O’Connor, K. (2005). Seven practices for effective learning. Educational Leadership, 63(3), 10-17. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/nov05/vol63/num03/Seven-Practices-for-Effective-Learning.aspx

Media Insight Project. (2017). Associated Press & NORC. http://www.mediainsight.org/Pages/default.aspx

Michalak, R. & Rysavy, M. D. T. (2019). Learning what they want: Chinese students’ perceptions of electronic library services. In D. Mueller (Ed.), ACRL 2019: Recasting the Narrative (pp. 176-182). Association of College & Research Libraries. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2019/LearningWhatTheyWant.pdf

Pattee, A. (2008). What do you know? Applying the K-W-L method to the reference transaction with children. Children & Libraries: The Journal of the Association for Library Service to Children, 6(1), 30-39.

Pendergrass, E. (2013/2014). Differentiation: It starts with pre-assessment. Educational Leadership, 71(4). http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational_leadership/dec13/vol71/num04/Differentiation@_It_Starts_with_Pre-Assessment.aspx

United States Department of Education. (2015). Demographic and enrollment characteristics of nontraditional undergraduates: 2011-12. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2015/2015025.pdf

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Wineburg, S., McGrew, S., Breakstone, J., & Ortega, T. (2016). Evaluating information: The cornerstone of civic online reasoning. The Stanford History Education Group. https://purl.stanford.edu/fv751yt5934