The Call of Public Life: Critique, Repair, and the Humanities

Jessica Harless

If the humanities are to respond to the precarities and the possibilities of our times, we must make use not only of their capacity to provoke and challenge but also their power to create. This was the charge leveled by the presenters of “Humanities and Public Life” who, slotted alongside sister symposia focusing on topics like brain plasticity, epidemiology, and natural resource resilience, sought to make sense of the university’s service to the public good and the promise held by humanities research in particular.

In welcoming participants, Anke Pinkert (University of Illinois, Germanic Languages and Literature) formally introduced the twin imperatives of critique and repair, suggesting that while the former is often what the humanities seem to be for, it’s in fact repair that is greatly needed. Often in humanities research, Pinkert noted, we undertake inventory and analysis of what’s been deranged (referring deftly to the opening keynote address from Amitav Ghosh the night before and perhaps hinting at Elaine Scarry’s imminent nuclear address). In addition, we must work to rearrange and reassemble, to change our states of affairs. Events such as the symposium itself serve as a good start by publicly convening folks for formation and for participation. Pinkert urged for more showing up and more being with others who also want change—it is easy, she assured, to just show up.

Morning keynote lecturer Elaine Scarry (Harvard University, English) also called for us to imagine public formations and participation as a substantial response, in this case to the threat of nuclear armament and the reality of solitary nuclear decision making. She blitzed the room with statistics about the size, scale, and scope of current worldwide arsenals and confirmed that use of even 1% of those stores would result in one billion deaths within the first month. It was stunning to think of the physical and technological architecture required to support such a scheme. Scarry’s real worry, however, reached beyond the magnitude of our armament toward the fact that all of this architecture falls within but a few hands. In the U.S., the use of nuclear weapons revolves around “presidential first use;” that is, without debate, dissent, explanation, or even transparency, the president may unilaterally call for launches and deployments of weapons. The “good news,” as Scarry put it, was that engaged governance has proved time and again to temper nuclear frenzy, and that deliberation and ratified agreements have consistently disarmed and denuked those areas of the world that have engaged them. Her U.S. hope is to engage “intervening layers of humanity”—public formations, dissidence, Congressional oversight, electoral ratification—to buffer and govern us away from a quick trigger.

Yet, Scarry held doubts about the public’s capacity to share such governance. She called out our current sleepwalking complacency as part of nukes’ mental and moral architecture—the commitments, compromises, and silences also necessary for and complicit in the nuclear scheme. Scarry yearned to understand who might hear the threat in her message, who might be listening on her wavelength—who might get it—but feared such strong complacency indicated the loss of our care for justice, our belief that the arsenals cannot be undone, or our hope that sleepwalking will acquit us from culpability. However, after the bright response of Hina Nazar (University of Illinois, English) it seemed that rather than a deafness what we might suffer is a kind of forgetting. Complacency is a signal that it’s actually our ways to publicly form that have been disarmed, that we have been drained of the means of public formation, participation, and shared governance. Remembering the places and roles we could occupy within the architecture would address what Nazar suggested was a rotted social contract. She proposed, for example, that we lean on the interpretation of the Second Amendment and its indication of distributions of action, injury, and consent across the populace to re-ignite visions of socially contracted shared power. If the nuclear risk could be all of our own risk, the harm be harm to each of us, and the power to consent/dissent be a power afforded to all, shared responsibility could perhaps surface in place of such helpless, overwhelmed complacency.

Shared responsibility then emerged as central to Carolyn Rouse’s (Princeton University, Anthropology) keynote call that we reject reparations as repayments of moral debts. During her years developing and building a high school in Ghana, Rouse first discovered the insufficiency of formal juridical processes. The village’s attempts at individual justice and dispute settlement were not reparative; they did not meet the community’s needs for forgiveness and social integration. All formal ways of repaying debt, and reparative discourses, in particular, serve to impose charity and burden upon receivers and to reinforce existing power structures between harmer and harmed. Reparations, Rouse feared, attempt to formally calculate and concretize groups and their pasts, to flatten difference, and to freeze history. Respondent Colleen Murphy (University of Illinois, Law) dubbed such traditional measures attempts at “corrective justice,” in which the aim is to re-achieve a status enjoyed before any infliction of harm. Instead, Murphy proposed an alternative “transitional justice,” a more symbolic acknowledgment of harm. Redemption rather than reparations, Rouse agreed, points the way forward and requires that we rewrite and remix history, rethink and redraw our categories of harmer and harmed, and crucially, reframe all of ourselves as responsible for taking on the consequences together.

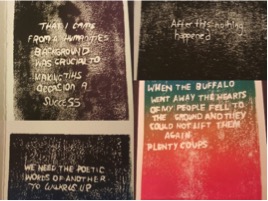

The midday encounters provided to the symposium by Illinois graduate students from the semester’s “Learning Publics” seminar only served to highlight this emerging necessity for shared, intervening, responsible formations. In particular, the collective reading experience designed by Angela Baldus (University of Illinois, Art Education Graduate Student) led the group to participate in and publicly perform an in-the-moment shared expression. As small, multicolored, hand-pressed cards were passed through the audience, participants were each met with the words of Plenty Coups, last chief of the Crow Nation: “When the buffalo went away, the hearts of my people fell to the ground and they could not lift them again” (quoted in Lear, 2006). As a microphone followed closely behind, participants each unfolded their cards and read aloud the series of responses revealed. “After this nothing happened,” lamented a dozen or so Plenty Coups. “That I came from a humanities background was crucial to making this occasion a success,” recited a handful of Jonathan Lears (2014), recounting his dialogue about radical imagination with the Crow people. And throughout the crowd, a range of voices both high and low repeated Lear’s confession of his own shaken complacency: “We need the poetic words of another to wake us up” (Lear, 2014).

Multiple voices also blended into the day via video vignette, as seminar students shared snippets of their unfolding research on public spaces within the city of Champaign, the publicness of religious groups, and the dynamics of public university housing. Later on, a panel of students representing the Public History Research Cluster, Education Justice Project, Spanish in the Community, and the Odyssey Project highlighted the ways in which Illinois currently seeks to connect to the immediate communities of Champaign and Urbana, undertake collaborative research and learning beyond the bounds of campus, and increase the accessibility of the university and its resources.

If Scarry’s question remained hanging in the room about who might be listening, hearing, and compelled, Romand Coles’s (Australian Catholic University, Institute for Social Justice) afternoon keynote indicated that he was dialed in and tuned up to deliver intense listening. He claimed that this capacity, to be receptive and hear the call of calls, is our vocational calling in the humanities; to be ready for and responsive to polyphonic sounds and voices—ecological, economic, political, educational—is to be engaged in a “full-bodied receptivity.” While Coles indicated that such receptivity could be powerful and effective in our cacophonous, dissonant times, respondent Melissa Orlie (University of Illinois, Political Science) made clear that dialing into such wavelengths was, in fact, a necessity for our subsistence. As they are, technological, economic, and political systems cannot muster enough salve or promise enough progress.

For Coles, this meant a much-needed injection of more publicness into the public university, via increased communication, extended communities, and broadened scholarship. To illustrate, he pointed to his time co-leading an action research initiative at Northern Arizona University. First-year undergraduate seminars studied tenets of public narrative and community organizing, then teamed with particular Flagstaff groups and organizations around explicit community needs. Students engaged in intense reflection upon their own selves, communities, places, and stories, which they practiced sharing and hearing with each other in preparation to work receptively and in relation with their community partners. This publicly engaged approach both democratized the institution—by increasing student persistence at NAU, retaining the participating faculty, and increasing community partners over time—and was able to un-fix and re-animate the habits of NAU’s humanities, the ways of thinking, and the modes of address. Coles’s desert mountain example brought together and brought to life all of the day’s attempts to tune into and hear what is around us; to form, share, and undertake together; and to alloy our usual means of interpretation with concrete action.

Discussion about the potential of engaged projects and problem-based collaboration continued into the closing panel, in which one participant asked whether such initiatives could be the practical way to more forcefully center the humanities within universities and to combat the withering and shuttering of humanities departments. Are there ways we should think not about how the humanities are capable of repairing, but how we might need to repair the humanities themselves? Rouse agreed that collaborative work among humanists, social scientists, and natural scientists, if truly collaborative, could lead humanities courses to more vitality and adaptation. But she also re-emphasized the sheer power of our most classic humanist tendencies. All of our current, nasty, intractable problems—the financial crash, climate crisis, and perpetual wars—will not be solved by more, faster, or brawnier technical expertise but rather by the humanities’ stock-in-trade: ethics and imagination. The day delivered plenty of doing and showing public humanities, noted symposium co-director Chris Higgins (University of Illinois, Education Policy, Organization, and Leadership). Calls to act, to act as if, to act with radical hope, and to just show up rung out clearly and bent toward the possibilities of active progress, change, and repair. Yet, Higgins urged, we should also heed the call of the crucial first steps of doing: waking up, noticing, reflecting, asking, and questioning. This tradition, as evidenced throughout the day, is why the humanities are unique, valuable, and ultimately, so practical.

References

Lear, J. (2006). Radical hope: Ethics in the face of cultural devastation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lear, J. (2014). The call of another’s words. In P. Brooks & H. Jewett (Eds.), The humanities and public life. New York: Fordham University Press.