Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar

Item

- Title

- Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar

- Description

-

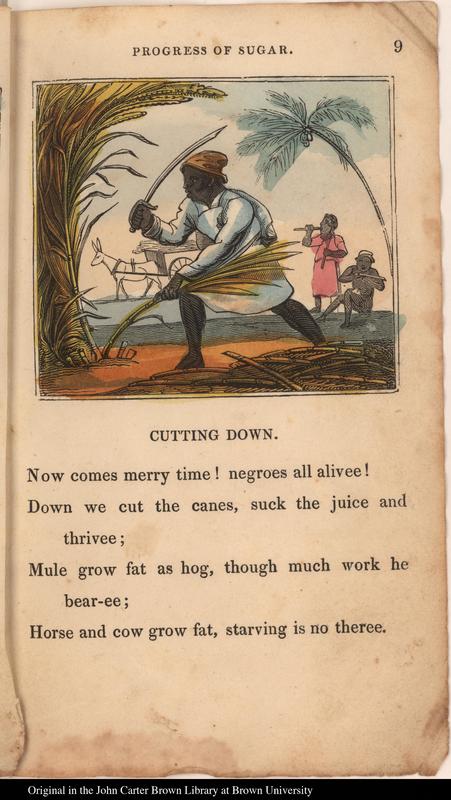

Each page of this chapbook features a single illustration depicting one part in the process of making sugar. Readers follow sugar production from slave labor in West Indies plantation cane fields to sugar refineries in British port cities, and finally, to confectioners shops where children purchase sugary treats. John Wallis printed a series of three such production stories for children on coffee, sugar, and cotton, each narrated in contrived dialect and doggerel poetry by the fictional character called Cuffy. Formerly enslaved in the West Indies and recently arrived in London, Cuffy promises to tell audiences what he knows about making these commodities in exchange for coin. The lighthearted account dismisses the cruelties endured by enslaved persons. Without explicitly supporting slavery, the book effectively defends slavery by depicting work on sugar plantations as so enjoyable that Cuffy regrets leaving. Cane harvesting is a “merry time!” when enslaved persons (denigrated here as livestock) “cut the canes, suck the juice and thrive; / Mule grow fat as hog, though much work he bear-ee; / Horse and cow grow far, starving is no there” (p9). In fact, many enslaved persons starved at harvest time because of the relentless pace of work. The later stages of sugar production in England are shown performed by free white persons. At the conclusion, Cuffy thanks the reader for “kind relief,” or money given to tell his story, directly involving readers in the slave-sugar economy as consumers.

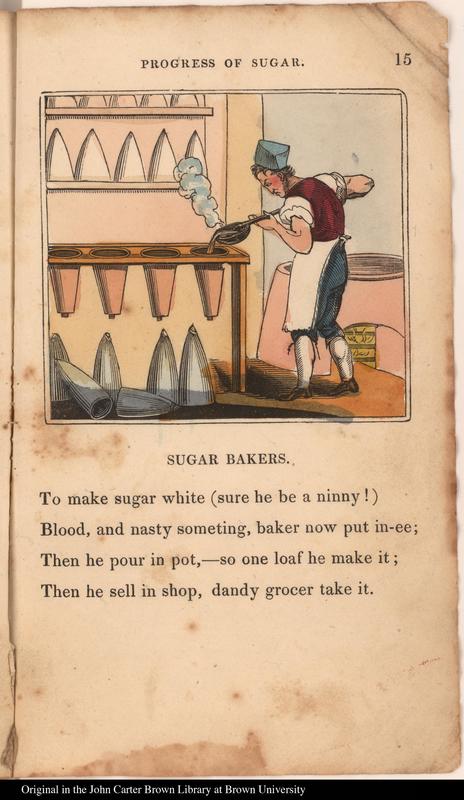

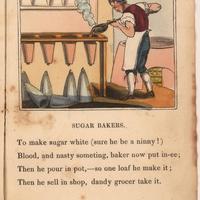

The chapbook is a literal account of the material process of growing, harvesting, refining, and packaging sugar. Yet the racial context of sugar production makes this process take on metaphorical meanings at every turn. Enslaved Africans created brown sugar, which was shipped to England, where free, predominantly white workers, refined the sugar to make it white. Sugar production stories used this language of brown, white, and refined, to continually remind readers of constructed racial hierarchies. Moreover, the process of refining sugar required animal blood, or as Cuffy describes: “To make sugar white (sure he be a ninny!) / Blood, and nasty something, baker now put in-ee” (p.15). Beginning in the 1790s, many abolitionist politicians and poets alluded to this fact to make eating slave sugar disgusting. People should boycott sugar, they argued, because slavery is a cannibalistic institution. Since harvesting cane causes the death of overworked, starved enslaved persons, sugar is essentially refined in human blood (See also Sandiford, 2000, p. 124; Sheller, 2003, pp. 88-97).

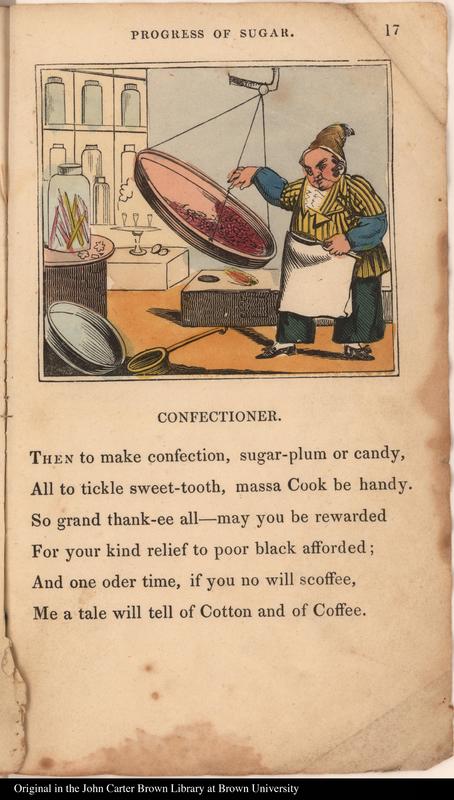

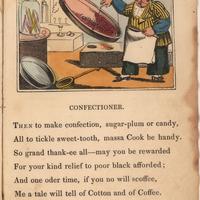

This abolitionist interpretation of the material process—what Timothy Morton calls the “blood sugar topos” (1998, p. 88)—was disseminated so widely that Wallis’s readers may recall this message while reading Cuffy’s account. The image of the “Confectioner,” for instance, shows a plump white man boiling a purple-red liquid in a large pan, suspended over an open stove flame. Although the text describes the liquid as “sugar-plum or candy,” the purple-red coloring may remind readers of human blood. Production stories that condone slavery, such as this one, tend to double-down on the literal, material process of refining sugar, as a way to avoid alluding to the blood sugar topos. This strategy is another example of how production stories can use scientific language to try to avoid addressing social conflict.

- Creator

- anonymous (author); Wallis, John (printer)

- Date

- 1823

- Subject

- proslavery literature

- production story

- John Wallis

- sugar

- Rights

- Public domain

- Obtained permission for digital images

- Courtesy of The John Carter Brown Library

- Source

- Read the full book at the Internet Archive

- Read the full book at the John Carter Brown Library exhibit

- Identifier

- Internet Archive External-identifier: urn:oclc:record:1042915382; John Carter Brown Library Call Number: D823 .C965t

- Bibliographic Citation

- [Wallis, John (publisher)]. Cuffy’s Description of the Progress of Sugar. London: E. Wallis, [1840].

- Site pages

- Chewing Cane