The Negro’s Complaint: A Poem. To Which Is Added, Pity for Poor Africans

Item- Title

- The Negro’s Complaint: A Poem. To Which Is Added, Pity for Poor Africans

- Description

-

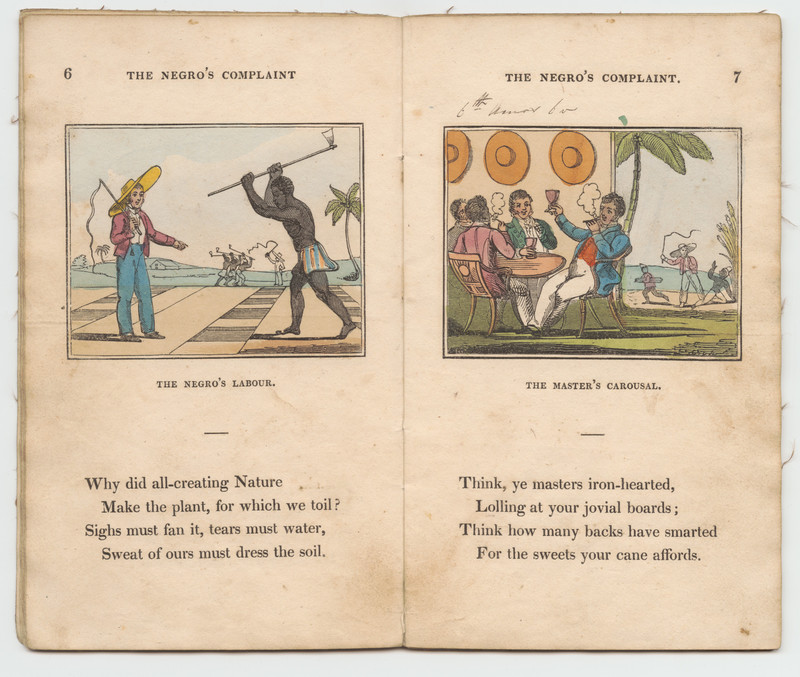

During the initial rise of the sugar boycotts in Britain, Cooper’s two poems were first printed and widely distributed in 1788 by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. They are not production stories. Nevertheless, this reprint edition by children’s publishers Harvey and Darton uses popular generic conventions for teaching children about commodities. “The Negro’s Complaint” uses the same visual layout as contemporaneous production stories by Opie and Wallis, with a titled illustration and poetry stanzas underneath. One spread shows enslaved Africans planting sugar cane in square holes (p. 6), an illustration nearly identical to those of other sugar production stories (e.g. William Newman, A history of a Pound of Sugar, p. 3). Drawing further parallels, Harvey and Darton used the same illustrator as Amelia Alderson Opie’s The Black Man’s Lament; or, How to Make Sugar, a sugar production story they published the same year.

Because of these editorial choices, Cooper’s poem takes on a new meaning for readers familiar with the production story form. Harvey and Darton draw comparisons between production stories and slave autobiographies, two forms that share narrative similarities. The titles of production stories (e.g. The Progress of Cotton; The Story of Sugar) make a commodity into a protagonist (e.g. sugar, cotton, coal), as if children are reading the commodity’s autobiography, and in fact, some fantastical production stories have commodities that come to life and speak their own life histories to human audiences. Autobiographies of former slaves, on the other hand, feature protagonists who were dehumanized as commodities for trade. When Cooper’s narrator, a fictional enslaved African, tells his own story, he follows in this tradition of abolitionist autobiographies. With their editorial choices, Harvey and Darton question why some production stories give agency to personified commodities while dehumanizing the enslaved persons forced to make them.

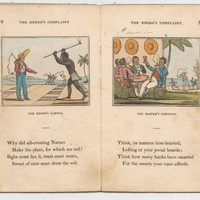

Readers familiar with production story conventions would recognize other places where this book plays with the form. The illustration titled “The Master’s Carousal” positions a standard illustration for the cane harvest in the background, in order to focus, instead, on the “jovial” masters drinking and smoking in the foreground. Readers must confront the “iron-hearted” white men, who drink rum and smoke tobacco, and feel shame that they, too, have enjoyed commodities made by enslaved persons.

The second poem in the collection, “Pity for Poor Africans,” has no illustrations, but its effect relies on familiarity with another popular children’s literature genre: the moral tale. The narrator is an Englishman who justifies eating sugar because a boycott would be ineffective, since others eat sugar anyway. He compares his choice to a boy who steals apples from an orchard, after he fails to convince his friends to abstain. Readers familiar with moral tales that warn boys not to steal apples would immediate recognize the speaker’s sophistry, then reevaluate their own choices on sugar consumption. The selection of both poems together suggests that Harvey and Darton considered how to frame abolitionist messages to speak to children, using literary conventions familiar to them.

- Creator

- Cowper, William

- Date

- 1826

- Subject

- abolitionist literature

- domestic consumption

- sugar

- Harvey and Darton

- Rights

- Public domain

- Obtained permission for digital images

- Courtesy of Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

- Identifier

- Kroch Library Rare & Manuscripts, Call number: Rare Books PR3382 .N3

- Bibliographic Citation

- Cowper, William. (1826). The Negro’s Complaint: A Poem. To which is added, Pity for Poor Africans. London: Harvey and Darton.