Why Manga Matters after Fukushima

Main Article Content

Abstract

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster of 2011 has created an alternative space for reportage and journalism. While much research has investigated how mainstream news media reported the Fukushima disaster in Japan and elsewhere, virtually absent is a scholarly investigation of the role of new media artworks in shaping what it means to be the Fukushima nuclear crisis. This study thus focuses on the role of Japanese manga among various new media artworks, and investigates how the disaster was represented in comics form.

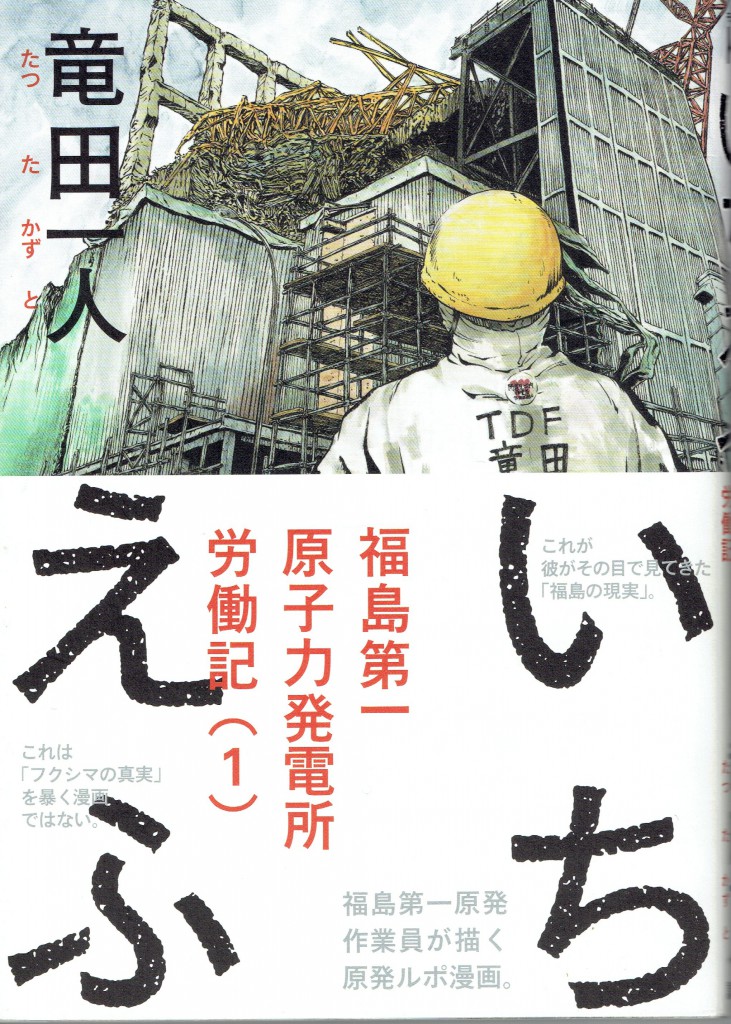

Among various Japanese manga on the Fukushima disaster, this paper focuses on examining a Japanese manga titled as Ichi Efu: Fukushima Daiichi genshiryoku hatsudensho rōdōki or 1F: A cleanup worker’s account of Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant (thereafter, 1F) written by Kazuto Tatsuta, one of the Japanese cleanup workers at the wrecked power plant. Originally published in Morning, a Japanese weekly manga magazine in 2013, 1F illuminates what the consequences of the Fukushima disaster looked like from the perspectives of a cleanup worker, providing an uncommon view of Fukushima for a wide variety of audiences including comic fans in Japan and elsewhere.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

References

Akira Fujitake, Nihon no Media (Tokyo: NHK Books, 2012).

Dirk Vanderbeke, “In the Art of the Beholder: Comics as Political Journalism,” in Comics as a Nexus of Cultures: Essays on the Interplay of Media, Disciplines and International Perspectives, eds. Mark Berninger, Jochen Ecke, and Gideon Haberkorn (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2010), 79–80.

“Dai 34 kai manga OPEN, Saishū Senkō Kekka Happyō!,” Morning, last modified October, 2013, accessed July 15, 2016, http://morning.moae.jp/news/475.

Duncan, Taylor and Stoddard, Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir, and Nonfiction, 1.

Elaine Lies, “Comic books champion debate on Fukushima disaster: Cartoonists broach sensitive topics by media but avoid politics,” Japan Times, June 29, 2014, accessed July 15, 2016, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/06/29/national/social-issues/comic-books-champion-debate-fukushima-disaster/.

For example, see Kazuhiro Sekine, “Purometeusu no wana: Manga Ichi Efu 7 mitamama kakou,” Asahi Shimbun, November 12, 2014, 3.

For media framing analysis, see, for example, Robert M. Entman, “Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm,” Journal of Communication 43, no. 4 (1993): 51–58; William A. Gamson and Andre Modigliani, “Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach,” American Journal of Sociology 95,no. 1 (1989): 1–37; and Todd Gitlin, The Whole World is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the News Left (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980): and others.

For the scholarship of nonfiction comics, see, for example, Randy Duncan, Michael Ray Taylor, and David Stoddard, Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir, and Nonfiction(New York: Routledge, 2016); Amy Kiste Nyberg, “Comics Journalism: Drawing on Words to Picture the Past in Safe Area Goražde” in Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods, eds. Matthew J. Smith, and Rundy Duncan (New York: Routledge, 2012), 116–128; Benjamin Woo, “Reconsidering Comics Journalism: Information and Experience in Joe Sacco’s Palestine” in The Rise and Reason of Comics and Graphic Literature: Critical Essays on the Form, eds. Joyce Goggin and Dan Hassler-Forest (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2010), 166– 177; and Kristian Williams, “The Case for comics journalism,” Columbia Journalism Review 43, no. 6 (2005): 51–55: and others.

Gennifer Weisenfeld, Imagining Disaster: Tokyo and Visual Culture of Japan’s Great Earthquake of 1923 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 217.

Hiroshi Kainuma, “Ichi Efu: Fukushima Daiichi genshiryoku hatsudensho rōdōki (1) Tatsuta Kazuto cho,” Yomiuri Shimbun, June 1, 2014, 6.

Ian Condry, The Soul of Anime: Collaborative Creativity and Japan’s Media Success Story (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 107–108.

Ibid.

“Ima Fukushima o egaku koto: Mangakatachi no mosaku,” NHK, last modified June, 2014, accessed July 15, 2016, http://www.nhk.or.jp/gendai/articles/3506/index.html: Shōji Nomura, “300 nenkan kiezu, 100 baichō no noushuku gempatsu jiko kara 4 nen: Shokuhin no hōshanō osen wa ima,” AERA, March 9, 2015, 26.

Julia Round, “’Be Vewy, Vewy Quiet. We’re hunting wippers’: A Barthesian Analysis of the Construction of Fact and Fiction in Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell,” in the Rise and Reason of Comics and Graphic Literature: Critical Essays on the Form, eds. Joyce Goggin and Dan Hassler-Forest (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2010), 200.

Kazuhiro Sekine, “Purometeusu no wana: Manga Ichi Efu 12 ‘Dakara nani?’ hihan mo,” Asahi Shimbun, November 17, 2014, 3.

Kazuhiro Sekine, “Purometeusu no wana: Manga Ichi Efu 14 kasetsu ni hibiku shōwa kayō,” Asahi Shimbun, November 19, 2014, 3.

Ken Aoshima, “Gempatsu sagyōin ga manga rensai ‘mitamono o kiroku ni nokoshitai,’” Manichi Shimbun, April 28, 2014, 6.

Kensuke Nonami, “Sagyōin ga egaku ‘Ichi Efu’ Fukushima Daiichi gempatsu no nichijō, manga ni,” Asahi Shimbun (evening edition), April 26, 2014, 8.

“Mangaka wa naze Fukushima o egakunoka,” Mainichi Shimbun, June 13, 2014, 25.

Miso Suzuki, 3.11: Boku to Nihon ga Furueta Hi (Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten, 2012).

My analysis of Don’t Follow the Wind is based on a wide variety of online and offline materials on the exhibition. For the concept of the exhibition in more detail, see Noi Sawaragi, Chim↑Pom and Don’t Follow the Wind Jikkō Iinkai, eds., Don’t Follow the Wind: Tenrankai Kōshiki Katarogu 2015 (Tokyo: Kawade Shobō Shinsha, 2015).

Nyberg, “Comics Journalism: Drawing on Words to Picture the Past in Safe Area Goražde,” 116.

Peter Gutierrez, “Peter Gutierrez on Scott McCloud,” in Exploring the Roots of Digital and Media Literacy through Personal Narrative, ed. Renee Hobbs (Pennsylvania: Temple University Press, 2016), 217.

Raymond Williams, Culture and Society: 1780−1950 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1958), 299–300.

Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1993).

See Howard S. Becker, Art Worlds (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984).

See, for example, Barbara Geilhorn and Kristina Iwata-Weickgenannt, Fukushima and the Arts: Negotiating Nuclear Disaster (New York: Routledge, 2016) and Ferilli Guido et al., eds., 3.11 e no Bunka kara no Ōto: Commitment to 3.11 24 nin no Kurieitā Bunkajin e no Intabyū (Kyoto: Akaakasha, 2016).

See, for example, Elaine Lies, “Comic books champion debate on Fukushima disaster: Cartoonists broach sensitive topics by media but avoid politics”; Arnaud Vaulerin, “Au Japon, un mystérieux dessinateur raconte le quotidien des travailleurs de la centrale,” Libération, April, 21, 2014, accessed July 15, 2016, http://next.liberation.fr/livres/2014/04/21/fukushima-cases-catastrophes_1001809: Mami Toya, “‘Hibaku de hakketsubyō’ wa dema. Yokunatta bubum mo tsutaete. Rupo manga ‘Ichi Efu’ sakusha no Tatsuta Kazuto san, gempatsu hōdō ni gigi,” Sankei Shimbun, November 9, 2015, accessed July 15, 2016, http://www.sankei.com/premium/news/151109/prm1511090004-n1.html.

See, for example, Kenichi Nakazawa, Barefoot Gen vol.1: A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima(San Francisco: Last Gasp of San Francisco, 2004); Osamu Tezuka, Ken 1 Tanteichō(Tokyo: Kodansha, 2011); and Yoshihiro Saegusa, Cherunobuiri no Shōnen tachi(Tokyo: Kodansha, 1992).

See, for example, Thierry Groensteen, “Definitions” in the French Comics Theory Reader, eds. Jeet Heer, and Kent Worcester (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2014), 93–114.

Shōji Nomura, “300 nenkan kiezu, 100 baichō no noushuku gempatsu jiko kara 4 nen: Shokuhin no hōshano osen wa ima,” AERA, March 9, 2015, 26.

Tatsuta, Ichi Efu: Fukushima Daiichi Genshiryoku Hatsudensho Rōdōki 1, 33.

Tetsu Kariya, Oishimbo 111: Fukushima no Shinjitsu 2 (Tokyo: Shōgakukan, 2014).

The page number of the manga Ichi Efu in this study is based on Kazuto Tatsuta, Ichi Efu: Fukushima Daiichi Genshiryoku Hatsudensho Rōdōki 1.

Thierry Groensteen, “The Impossible Definition” in A Comics Studies Reader, eds. Ann Miller, and Bart Beaty (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014), 128.

Tokyo Art Beat’s Website, “Switch x Tab Tokubetsu Kikaku Hirihiri suru Āto: Dialogue Ushiro Ryūta (Chim↑Pom) x Kubota Kenji (Kyureitā),” Tokyo Art Beat, last modified September 29, 2015, accessed July 15, 2016, http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/tablog/entries.ja/2015/09/switch-tab-dontfollowthewind-chimpom-ryutaushiro-kenjikubota.html.

Vanderbeke, “In the Art of the Beholder: Comics as Political Journalism,” 80.

Watari-Um’s Official Website, “Don’t Follow the Wind: Non Visitor Center,” Watari-um, last modified September, 2015, accessed July 15, 2016, http://www.watarium.co.jp/exhibition/1509DFW_NVC/index2.html.

Woo, “Reconsidering Comics Journalism: Information and Experience in Joe Sacco’s Palestine,” 172–173.

Yuki Inamura and Tatsuya Hoshino, “Hairo no gemba 5: Sagyō no genjitsu manga de rupo,” Yomiuri Shimbun, June 5, 2015, 37.