3 Ruins and Resilience: Preserving the Legacy of the Kyrgyz Soviet Era

Kateřina Zäch

Buildings are not merely physical structures; they serve as tangible embodiments of social and economic power, and many have a rich and complex history. The essence of everyday life lies within their walls, intricately connected to the local landscape. That a profound interplay exists between everyday activities and buildings calls for a fresh perspective on buildings as infrastructure, which this paper aims to do, drawing on insights from James Anderson, Ashley Carse, and others, to understand the lasting impact of past Soviet policies on the buildings and people of Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.[1]

While heritage studies often overlook how buildings intersect with people’s working lives and leisure activities, we can, by figuratively journeying into the past and observing buildings in their decaying state, encourage a greater interest in preserving them as cultural heritage. These excursions offer valuable opportunities for contemplating their present condition and help to raise awareness of their significance even as they deteriorate. Indeed, comprehending the historical roles of these structures often yields insights into modern construction challenges and smooths their transition to the future.[2]

According to Chiara Ronchini, heritage is not a fixed and unchanging entity but rather a socially constructed and continuously evolving concept, closely intertwined with the everyday needs of people.[3] Similarly, Sybille Frank highlights the political dimension of heritage, whose buildings are often manipulated for political and ideological ends.[4] While infrastructure has traditionally been governed by state bureaucracies,[5] envisioning its future trajectory now requires understanding the emerging interplay between people, buildings, and the dynamics of everyday politics. These interactions shed light on the economic processes that often prioritize commercialization over all other factors, neglecting the cultural and social aspects that link them to the past.

The evolution of daily life and the distribution of societal development constitute a multifaceted process. Political motives can sometimes disconnect local actors from actively preserving their living spaces, giving rise to political debates concerning the ordinary aspects of individual lives and the social and cultural expectations entwined with them.[6] Nevertheless, examining infrastructure can enhance our understanding of the impact on people of “shared infrastructural poverty,”[7] which is shaped by prevailing political and economic dominance in both urban and rural settings.[8] During the Soviet era, institutions in Kyrgyzstan held significant control over the people, influencing their participation and shaping their experiences,[9] but while both Soviet and post-Soviet governments presented citizens with specific infrastructure choices, leading to diverse claims of local citizenship,[10] the post-socialist transition towards a market-based system ushered in additional processes, including fragmentation, consumerism, and social disparities.[11]

Caroline Humphrey’s research highlights how public perceptions of infrastructure can change when the extent of state control over its use becomes evident.[12] In many regions of Kyrgyzstan during its socialist years, infrastructure development was barely adequate for its intended purposes, and this deficiency became more apparent in the post-socialist period.[13] As a result, a decline in prioritizing social interaction and cultural support within city politics led to pivotal moments of political change, which, in turn, introduced new forms of infrastructure that fostered novel interactions, emotions, and feelings of estrangement.[14] Since the fall of the Soviet Union, a considerable number of buildings in Bishkek have lost their original purpose and fallen into decay, with many now awaiting demolition. However, there is a growing recognition of the importance of preserving these structures as social and cultural trends continue to evolve.

This article explores several critical aspects of infrastructure to highlight the significance of preservation efforts in Bishkek. First, it considers a building’s temporal dimension as a social construct, as discussed by Nikita Besedovsky et al.[15] This perspective underscores the importance of understanding how societal attitudes towards time influence decisions about preservation and development. Second, it explores the influence of political structures on the fate of these buildings, as discussed by Colin McFarlane and Jonathan Rutherford.[16] Political decisions and policies can significantly impact the preservation of historical architecture and influence the choices made about their future use. Finally, the article considers the transformation of daily practices and processes in the context of changing urban landscapes, drawing on research by Hillary Angelo and David Calhoun, and Susan Star and Karen Ruhleder.[17]

The evolution of the city of Bishkek involved changes in the interactions between people and their structures and spaces. Consequently, preservation strategies must adapt and consider the changing cultural and social dynamics of the city. Because a built environment plays a pivotal role in shaping how individuals navigate and experience the city, emphasizing the need to comprehend how the preservation or removal of specific structures often influences the overall urban fabric. In this context, infrastructure assumes a significant role in shaping everyday life, as Jennifer Robinson argues.[18] Here, however, only a few buildings in Bishkek are highlighted, with a reassessment of their nature and the underlying motives and incentives that drove their construction, use, and maintenance to cater to the requirements of the city’s inhabitants.

Preserving Everyday Infrastructure

Preservation practices have always been important for safeguarding land that holds the essence of history, language, culture, and identity, and evolved in harmony with human communities. Among the various aspects of cultural heritage, buildings stand as powerful reflections of their time and place, offering profound insights into the functioning and adaptability of local politics. Consequently, political action should prioritize their preservation above most, if not all, other considerations.[19] After all, once gone, they are gone forever, and with them a part of a people’s heritage. Only by recognizing and preserving their historical, social, and cultural significance, can we ensure that they continue to serve as living testaments to the past while enriching the present and shaping the future of the communities to which they belong.

David Harvey stresses the importance of recognizing the diverse and intricate spatial practices within societies and the necessity of representing and generalizing them in preservation efforts.[20] Indeed, social change is intricately interwoven with the historical dimensions of time and place, carrying profound ideological implications with it. Embracing Harvey’s perspective leads us to recognize the influence of past possibilities on the present, which underscores the significance of social interactions, human actions, and engagement in overcoming any reluctance to preserve our buildings. Tauri Tuvikene et al. likewise highlight the significance of the past, whose neglect can lead to people failing to recognize the profound bond they have with their buildings and infrastructure.[21]

Although it may be unfashionable to say so, many of Bishkek’s Soviet buildings were designed to facilitate cultural and leisure activities, emphasizing the significant role of heritage in shaping everyday life through human practices. By understanding and appreciating the thoughtful design and historical context of these buildings, we can truly grasp their value in fostering social interactions, cultural expression, and a sense of belonging within the urban fabric. Preserving and comprehending their historical connections not only fosters a deeper appreciation of the city’s identity but also strengthens the bond between its residents and their living spaces. In culturally diverse contexts such as Central Asia, the preservation of cultural sites, including material objects and places, holds immense importance; as Rodney Harrison’s concept of “absent heritage” reminds us, a building’s cultural or historical elements are often excluded or neglected in official narratives and representations of a place or community.[22]

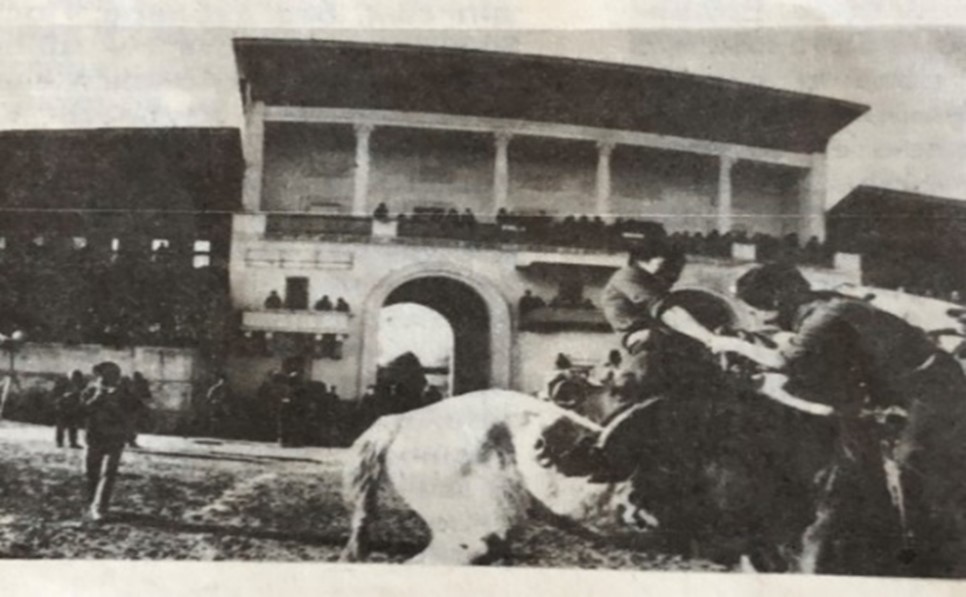

To initiate the preservation process in Bishkek, it is essential to consider its historical landscape, which includes a diverse array of ceremonial, commemorative, and recreational buildings that evolved with the development of human settlements. The everyday use of these structures has profoundly influenced social and institutional practices that improved the quality of life while maintaining their intrinsic significance. These buildings not only represent the identities of individual people and groups but also embody modernist architectural concepts while preserving local cultural expressions. A compelling illustration of this rich cultural heritage is Bishkek’s Ak-Kula Hippodrome, which not only hosted traditional equine races but also served as a poignant reminder of the country’s nomadic past. Similarly, the Bishkek Planetarium offers a platform for exploring the cosmos while reflecting the city’s commitment to education and knowledge.

Recognizing the historical, cultural, and architectural value of Bishkek’s buildings is crucial for setting the stage for comprehensive preservation efforts that safeguard the city’s identity and heritage. Through the preservation of these cultural sites, we pay homage to the past, enrich the present, and establish an enduring legacy for future generations to cherish and learn from. What is more, such preservation endeavors go far beyond the physical structures themselves, playing a pivotal role in fostering a deep sense of pride, belonging, and unity in Bishkek’s diverse communities.

Preservation offers additional benefits, playing a pivotal role in boosting tourism, education, and the overall well-being of a community. By maintaining a strong link to its origins, Bishkek provides tourists with a distinctive travel experience, while its residents deepen their appreciation and knowledge of its historical and cultural heritage. This conservation not only protects the tangible remnants of the city’s past but also fosters intangible aspects such as collective memory and local identity. As a result, such endeavors should contribute to a tighter social fabric and cultivate a profound sense of community and belonging among the inhabitants of Bishkek who call the city their home.

Preserving the Tapestry of Heritage: Everyday Life in Kyrgyz and Contemporary Development

Both the present writer and K. Anne Pyburn, whose “Authentic Kyrgyzstan” provides invaluable insights into archeological reconstructions,[23] spent time in Kyrgyzstan, and this experience significantly informs and strengthens both of our perspectives. Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize the difficulty in being certain or even confident about the daily lives of Bishkek residents,[24] who encounter and inhabit their city without theoretical interventions.[25] While both Pyburn and I endeavor to approach the subject impartially and recognize the diverse relationships that Bishkek residents have with their heritage, we can experience and appreciate that heritage only as outsiders. In my case, I want only to respect and understand the perspectives and experiences of the Bishkek people while shedding light on the importance of heritage preservation and its impact on their lives and cultural identity.

Although my observations in Bishkek led to the recognition that specific buildings serve as a form of human infrastructure, it is essential to clarify that my intention is not to impose predetermined needs or solutions on local actors. Instead, I aim to use my encounters with them as a starting point to stimulate deeper reflections on how people value their everyday buildings. For me, this approach is important to investigate whether the impact of hidden political agendas is inadvertently overlooked and influences people’s lives and positions them for specific roles.[26]

To address these dynamics, it is, I believe, necessary to consider new approaches, which may prove more effective in countering the control exerted by state bureaucracies.[27] The heritage of everyday life is deeply interwoven into the fabric of cultural variations and diversity, making it imperative to engage in nuanced and context-sensitive explorations that respect the perspectives and agency of local communities. Only by acknowledging the complexities and subtleties of people, buildings and political forces, and their interactions, can we better appreciate the significance of everyday heritage and its potential for empowering communities.

Still, the question remains whether this cultural richness can be fully experienced if free activities are reduced, say, to visits to the local cinema or shopping mall. Because the way people live is deeply influenced by the presence and impact of infrastructural sites, when one infrastructure disappears, we must move on to others, which can evoke both pleasant surprises and bitter disappointments. Although many people enjoy strolling through shopping malls, this can give the impression that buildings such as the Ak-Kula Hippodrome or the Bishkek Planetarium are unwanted. This may even accelerate their closure, as it can with other important cultural institutions such as museums and galleries. In short, we cannot quarantine past practices from the influence of contemporary culture.

What is also true is that actions and experiences are undeniably influenced by the spaces and places people inhabit. The distinction between outside and inside environments assumes that all indoor activities take place within buildings, but local exterior landscapes are dotted with places that hold deep symbolic meanings for local actors.[28] For example, the Kyrgyz yurts (of which there are many) hold immense significance in Kyrgyz culture and identity, particularly in rural areas, or the now-closed Café Ulitka in Bishkek, which embodies the unique charm of the city and offers a serene green setting. Understanding Ulitka in this context can provide valuable insights into a specific place, as it represents the harmonious blend of nature and architecture and mirrors the essence of Ulitka itself.

What is more, the preservation of buildings in Kyrgyzstan requires their re-evaluation, especially in light of the evolving social dynamics influenced by new forms of living, consumerism, and economic challenges. These factors significantly impact how the past is managed and how heritage preservation is approached. Additionally, the governance of daily life at the local level is continually influenced by the political regimes,[29] further shaping decisions related to heritage and infrastructure. To be effective, infrastructure must not only be physically sound but also incorporate social rules as integral components.[30] The use and management of buildings should align with the needs and values of the local communities they serve.

Certainly, everyday life and heritage are deeply rooted in the social reality of how people live and interact with their environment.[31] As part of the built environment, infrastructure plays a crucial role in supporting and enhancing local culture. Therefore, it is essential to consider the impact of infrastructure decisions on the preservation and promotion of local cultural practices, traditions, and identities. Striking a balance between modernization and heritage preservation is never easy, requiring thoughtful consideration and involvement of the community to ensure that the built environment reflects and contributes to the richness of local culture, but there is no better way to preserve the past for present and future generations to enjoy.

Oral Heritage

Kyrgyzstan’s folklore has a deep connection to its rural areas, and the oral heritage sites hold invaluable insights into the development of Islam that has profoundly influenced the identity, culture, and life paths of communities in Central Asia. The interplay of tradition and religion has woven a rich tapestry of narratives that resonate throughout the region, shaping the collective consciousness of its people. The Soviet era similarly left an indelible mark on Kyrgyz heritage. In Bishkek and beyond, Soviet monuments, statues, and buildings stand as poignant reminders of that period in history, each structure serving as a time capsule preserving the architectural and artistic styles prevalent at that time. The remnants of the Soviet era stand as a testament to the country’s complex history and the enduring impact of that era on its cultural and built environment.

Particularly noteworthy are the intricate patterns adorning the facades of buildings that depict motifs echoing the nation’s history and cultural heritage. These patterns often feature representations of plants, animals, and geometric shapes, each carrying layers of significance and meaning. They also serve as visual representations of the cultural tapestry woven into Kyrgyzstan’s architectural landscape, reflecting the creativity, craftsmanship, and artistic sensibilities of its people. This wide array of cultural treasures contributes to a multifaceted identity that beautifully mirrors the country’s evolution and cultural richness.

Bridging Past and Present: The Historical Landscape of Everyday Buildings in Kyrgyzstan

The decline in interest in visiting cultural sites in Kyrgyzstan and the increasing dominance of large malls as public entertainment spaces reflect broader global trends related to consumerism and changing societal preferences. This shift has several implications for the preservation of cultural heritage and the social significance of architectural spaces. The rise of consumerism and modern entertainment options have led to changes in how people spend their leisure time. Large malls offer a wide range of amenities, including shopping, dining, cinemas, and other recreational activities, all under one roof, and this convenience and variety attract a larger audience compared to traditional cultural venues with more specific experiences. The decline in interest in cultural sites also raises concerns about the preservation and promotion of Kyrgyzstan’s cultural heritage. Cultural venues, museums, and historic sites are essential for preserving a nation’s history, traditions, and identity, and when they are overshadowed by commercial spaces, there is a risk of losing touch with the country’s heritage and identity.

However, by considering the historical significance of these buildings and understanding their role in shaping everyday life, we can better appreciate their value as part of Bishkek’s cultural heritage. This understanding allows us to redefine their current relevance in the present context and explore ways to revitalize them as meaningful social spaces in contemporary society. It also helps to bridge the gap between past and present, fostering a renewed appreciation for Bishkek’s cultural sites and their role in enriching the lives of its residents.

One such building is the Bishkek Planetarium, which has a rich history as a hub for human curiosity and education, particularly during the Soviet era. Although it has been closed and abandoned for the past two decades—facing legal battles and a lack of state support and sponsorships that hinder its restoration and preservation—its cultural value is undeniable. Preserving this historic gem goes beyond preserving a physical structure; it will safeguard the collective memory of the city and foster a sense of continuity between generations. Reviving the Bishkek Planetarium will enable future residents to connect with the aspirations and achievements of their predecessors, with insights into Bishkek’s scientific and cultural heritage as a center for education, science, and community engagement.

Similarly, the neglected state of the Ak-Kula Hippodrome underscores the urgency for effective heritage preservation strategies. Originally built in 1947 as a venue for national equine games and sports competitions, the building was thoughtfully designed to reflect the essence of Kyrgyz culture. However, over time, the building has fallen into disrepair and currently fails to meet safety regulations. Its uncertain future has sparked heated debates, with some proposing to demolish it in favor of a football stadium and others hoping to restore it to its original state. While the building’s deterioration raises legitimate concerns about the cost of preservation, it also represents the principal issue: the neglect of cultural heritage and the prioritization of commercial over preservation efforts.

The historical context of the Soviet era in Kyrgyzstan meant a time when the government played a significant role in organizing leisure activities and promoting cultural engagement among the population. During this period, many buildings and venues were constructed to foster a sense of community, promote education, and celebrate the achievements of the Soviet system. However, as Kyrgyzstan transitioned to an independent republic, it faced many challenges in maintaining and revitalizing these historic buildings. Financial constraints have had a significant impact on the government’s ability to plan and transform the city while preserving and using these buildings to their full potential.

The example of the Ak-Kula Hippodrome underscores the difficulties in preserving historical sites and implementing revitalization projects. Limited financial resources may lead to compromises in the design and construction processes, potentially affecting the integrity of the historical site and its cultural significance. Additionally, the lack of participation from local communities and heritage organizations can result in decisions that do not align with the community’s values or needs.

The emphasis on the historical significance and cultural value of these buildings by groups advocating for their preservation is crucial for recognizing the tangible heritage they represent. Such buildings hold symbolic as well as historical meaning for the people of Kyrgyzstan, reflecting the nation’s unique culture and identity, and demolishing them will lead to the loss of a tangible heritage and sever the connection between the people and their history.

To address these challenges, a collaborative approach involving various stakeholders, including the government, local communities, heritage organizations, and the private sector, is vital. By pooling resources and expertise, viable preservation and revitalization strategies can be formulated to ensure the sustainable conservation of culturally significant buildings. Finding a balanced approach that considers historical significance, cultural value, and present financial realities will not be easy, but it is necessary for determining the future of these buildings.

The example of Café Ulitka and the demolition of the once-grand Issyk-Kul Hotel both underscore the importance of strategic planning and collaboration in preserving a city’s cultural spaces and heritage. While balancing economic development with cultural heritage preservation is a delicate task requiring thoughtful consideration and the involvement of various stakeholders, a collaborative approach to urban planning can balance economic development with cultural heritage preservation, ensuring that a city respects its past while embracing the future. By considering the historical, cultural, and social value of buildings, cities can evolve in a manner that respects their heritage and ensures sustainable and inclusive development of urban spaces. Prioritizing cultural heritage preservation enriches a city’s character and fosters a deeper connection between its residents and their surroundings. Furthermore, incorporating historical landmarks into urban planning contributes to a more vibrant and meaningful urban environment that treasures the past while embracing the future.

Nor should private subsidies for funding restoration projects be overlooked. Private contributions can play a vital role in preserving historical landmarks and cultural heritage sites that have significant importance for the community. However, it is essential to recognize that not all buildings have access to such funding, leading to challenges in securing resources for restoration efforts. When private subsidies are not available, buildings may face economic constraints from state budgets. As a result, some may be financially unviable or declared terminally unsafe. These dynamics underscore the complexities at the intersection of political decisions, limited resources, and the preservation of historical and culturally important structures.

Therefore, the only practical solution is a balanced approach that involves various stakeholders. Government support, public-private partnerships, and community engagement can collectively contribute to safeguarding and celebrating the cultural heritage embodied by many buildings. Collaboration between the government and the private sector can create opportunities to fund restoration projects, with incentives such as tax benefits or heritage preservation grants to encourage private entities to invest in the preservation of historical landmarks. Moreover, fostering community involvement is vital for generating public support. Awareness-building campaigns that highlight the cultural and historic value of these buildings can instill a sense of ownership and pride within the community, and by engaging the public, there is a greater likelihood of garnering collective responsibility for cultural heritage preservation.

Unveiling the Extraordinary: The Rise of Meaning in the Mundane Through Appreciation

The pursuit of new developments and commercial interests, driven by neoliberal economics, has often resulted in the demolition of buildings with a rich cultural heritage. These decisions are influenced by rigid organizational practices and powerful actors who sometimes disregard the social values and relationships tied to these buildings. To understand the value and significance of buildings, we must value their history, cultural importance, and social use because buildings embody traditions, ideas, actions, religious beliefs, and cultural practices, as highlighted by Michael Herzfeld. Preservation efforts must aim to sustain and revitalize the social values and relationships associated with the past, connecting the materiality of these structures to their social functions.[32]

The criteria for preservation must also include the experiences and ways of living tied to a building’s history. However, recent trends in heritage preservation have, in some cases, led to undervaluing them and even to their demolition because few recognized their significance. A new approach is needed that recognizes the importance of buildings to people’s lives and that takes into account past experiences and local histories that influence the emergence of new material and cultural sites in the present and future. Harrison’s argument that heritage values are ascribed rather than intrinsic prompts a re-evaluation of the value of malleability and changes over time in conservation efforts. This approach allows us to appreciate the cultural significance embedded within buildings such as the Bishkek Planetarium or the Ak-Kula Hippodrome, recognizing their evolving nature and meaning.

Recognizing the privilege and importance of everyday buildings, from houses to public structures, is crucial. Such buildings provide the essential infrastructure for fulfilling daily needs and shape life’s landscape. As Harvey says, their relationship with the surrounding environment encompasses social, symbolic, psychological, biological, and physical dimensions; they are not static structures but dynamic entities deeply intertwined with social life, carrying the values, aspirations, and narratives of the community of which they are a part.[33] Buildings are places where human life unfolds, witnessing the struggles, joys, political actions, and educational experiences of the people who inhabit them, and preserving them is not just about conserving the physical structure but about preserving the stories, traditions, and connections that give them meaning.

Unveiling the Hidden Potential: The Educational Dimensions of Economic Rationalization

Visiting cultural institutions such as museums and theatres not only gives pleasure but also contributes to personal development and cultural sensitivity. These experiences create lasting memories and can strengthen family bonds. However, contemporary cultural buildings may be perceived differently from their predecessors, and some buildings may not receive the necessary support for their cultural activities if they are not seen in their original context.

As Johann Arnason highlights, communist regimes prioritized the modernization of education, with Soviet ideology influencing the natural sciences and the humanities differently than many modern schools do.[34] The ideological lens was even more prominent in the humanities, leading to the delegitimization of certain disciplines and the prohibition of “subversive” inquiries. The communist ideology permeated society, shaping social life under close supervision. Indeed, the Communist Party invested heavily in cultural and educational infrastructure, in buildings such as the Bishkek Planetarium, to encourage family participation in government-approved programs.

Martin Heidegger’s argument about technology’s destruction of authenticity and rootedness, rationalism, mass production, and mass value is relevant to this debate. The preference for consumerism and commercial activities, along with the rise of malls, has led to the neglect of Bishkek’s everyday buildings that carry historical and cultural value. There appears to be a regression in the understanding of the importance of education, culture, and leisure activities, particularly among the younger generation. Voices advocating for cultural activities have become less critical, and governance may not prioritize the cultivation of such activities. This social phenomenon raises concerns about different interests prevailing over the support for cultural preservation.[35]

It bears repeating that preserving cultural heritage is not simply about protecting physical structures; it is about safeguarding intangible values, memories, and experiences tied to these buildings, now detached from their initial function or ideology. We can rekindle, retell, and even recover the past through buildings and infrastructure without necessarily revering it.

Conclusion

The city of Bishkek has seen a remarkable transformation in its urban landscape, signifying a profound shift towards modernity and consumer culture. The proliferation of multi-story malls and the emergence of new lifestyles are clear indications of the city’s increasing emphasis on business development and consumerism. This transition, while emblematic of progress, also raises questions about preserving the city’s architectural heritage.

Amidst sweeping changes in Bishkek, there exists a unique opportunity to breathe new life and purpose into existing buildings through preservation initiatives. As the city evolves, it is crucial to strike a balance between development and safeguarding the historical fabric that defines the city’s identity. This vision of preserving Bishkek’s architectural heritage faces significant challenges, not least limited budgets and resources for restoration and conservation projects, and the neglect and decay of some historically significant buildings may have passed a point of no return.

Still, appreciating the intrinsic value of historic buildings is a necessary perspective that extends beyond Bishkek to every city in every country. These buildings are not mere lifeless entities but rather dynamic structures: they serve as important gathering places, cultural landmarks, and historical touchstones, connecting past and present. By identifying and prioritizing the renovation or preservation of buildings with profound cultural significance to the community, its people and policymakers can signal their commitment to preserving the city’s unique identity. This will mean not just financial investment but also fostering a sense of pride and ownership among citizens for their shared heritage. Finding a balance between limited resources and the preservation of cultural landmarks will demand meticulous planning, active community engagement, and long-term commitment.

Like many venerable towns and cities, Bishkek stands at a crossroads of progress and heritage, offering a chance to embrace its evolving identity while retaining the spirit of its past. By treading carefully and acknowledging the value of its cultural heritage, Bishkek can forge a path that ensures sustainable growth, community pride, and a vibrant, harmonious blend of the past and the future.

Acknowledgment

This article is part of a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 823961.

Bibliography

Allen, John. “Economics of Power and Space.” In Geographies of Economies, edited by R. Lee and J. Wills. London: Arnold, 1997.

Anderson, James E. Public Policymaking: An Introduction. 5th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Angelo, Hillary, and Craig Calhoun. “Infrastructures of the Social: An Invitation to Infrastructural Sociology.” April 2013. TS. NYLON Group, Berlin.

Angelo, Hillary, and Christine Hentschel. “Interactions with Infrastructure as Windows into Social Worlds: A Method for Critical Urban Studies: Introduction.” City 19, no. 2–3 (2015): 306–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1015275.

Arnason, Johann P. “Introduction.” Thesis Eleven 60, no. 1 (2000): v–vii. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513600060000001.

Besedovsky, Nikita, Fritz-Julius Grafe, Hanna Hilbrandt, and Hannes Langguth. “Time as Infrastructure.” City 23, no. 4–5 (2019): 580–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2019.1689726.

Carse, Ashley. “The Year 2013 in Sociocultural Anthropology: Cultures of Circulation and Anthropological Facts.” American Anthropologist 116, no. 2 (2014): 390–403.

Chelcea, Liviu, and Gergő Pulay. “Networked Infrastructures and the ‘Local’: Flows and Connectivity in a Post-Socialist City.” City 19, no. 2–3 (2015): 344–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1019231.

Feld, Steven, and Keith H. Basso, eds. Senses of Place. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 1996.

Frank, Sybille. Wall Memorials and Heritage: The Heritage Industry of Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie. New York/ London: Routledge, 2016.

Frunze. Entsiklopediia. The main editorial office of the Kyrgyz Soviet Encyclopedia. 1984.

Gandy, Matthew. “Landscape and Infrastructure in the Late-modern Metropolis.” In The New Blackwell Companion to the City, 58–65. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2011.

Geertz, Clifford. “Religious Belief and Economic Behavior in a Central Javanese Town.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 4, no. 2 (1956): 134–158.

Graham, Steven. “Switching Cities Off.” City 9, no. 2 (2005): 169–194.

Griffiths, Melanie. “Out of Time: The Temporal Uncertainties of Refused Asylum Seekers and Immigration Detainees.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40, no. 12 (2014): 1991–2009.

Harvey, David. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Cambridge, MA and Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1990.

Harvey, David. “Debates and Developments. The Right to the City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27, no. 4 (2003): 939–941.

Harrison, Rodney. Heritage: Critical Approaches. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

Harrison, Rodney. “Forgetting to Remember, Remembering to Forget: Late Modern Heritage Practices, Sustainability, and the ‘Crisis’ of Accumulation of the Past.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 19, no. 6 (2023): 579–595.

Herzfeld, Michael. “Heritage and the Right to the City: When Securing the Past Creates Insecurity in the Present.” Heritage & Society 8, no. 1 (2015): 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1179/2159032X15Z.00000000035.

Humphrey, Caroline. “Ideology in Infrastructure: Architecture and Soviet Imagination.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 11, no. 1 (2005): 39–58.

Law, John, and John Urry. “Enacting the Social Economy and Society.” 2004. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/resources/sociology-online-papers/papers/law-urry-enacting-the-social.pdf.

McFarlane, Colin, and Jon Rutherford. “Political Infrastructures: Governing and Experiencing the Fabric of the City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32, no. 2 (2008): 363–374.

Miller, Daniel. Material Culture and Mass Consumption. Oxford: Blackwell, 1987.

Miller, Daniel. “Why Some Things Matter.” In Material Cultures: Why Some Things Matter, edited by Daniel Miller. London: UCL Press, 1998.

Pyburn, Anne-Kristin. “Authentic Kyrgyzstan: Top-down Politics Meet Bottom-up Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24, no. 7 (2018): 709–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1390489.

Robinson, Jennifer. “Global and World Cities: A View from off the Map.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 26, no. 3 (2012): 531–554.

Ronchini, Chiara. “Cultural Paradigm Inertia and Urban Tourism.” In The Future of Tourism. Innovation and Sustainability, edited by E. Fayos-Solà and C. Cooper. Cham: Springer, 2019.

Star, Susan Leigh, and Karen Ruhleder. “Steps Toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces.” Information Systems Research 7, no. 1 (1996): 111–134.

Steinmüller, Wolfgang. Riskante Netze. Informations- und Kommunikationstechnik zwischen Technologieabschätzung und Technik-Gestaltung. Wien/München: Oldenbourg, 1990.

Taylor, Charles. “Modern Social Imaginaries.” Public Culture 14, no. 1 (2002): 91–94.

Tuvikene, Tauri, Sgibnev, Wladimir, Zupan, Dejan, Jovanović, Dušan, Neugebauer, Claudia S., and Jovano. “Post‐Socialist Infrastructuring.” Area 52, no. 3 (2020): 575–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12590.

Wacquant, Loïc. Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2008.

- See: James E. Anderson, Public Policymaking: An Introduction. 5th ed. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003); and Ashley Carse, “The Year 2013 in Sociocultural Anthropology: Cultures of Circulation and Anthropological Facts,” American Anthropologist 116, no. 2 (2014): 390–403. ↵

- Mathew Gandy, “Landscape and Infrastructure in the Late-modern Metropolis,” in The New Blackwell Companion to the City (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2011), 58–65. ↵

- Chiara Ronchini, “Cultural Paradigm Inertia and Urban Tourism,” in The Future of Tourism. Innovation and Sustainability, eds. E. Fayos-Solà and C. Cooper (Cham: Springer, 2019), 179–194. ↵

- Sybille Frank, Wall Memorials and Heritage: The Heritage Industry of Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie (New York/London: Routledge, 2016). ↵

- Melanie Griffiths, “Out of Time: The Temporal Uncertainties of Refused Asylum Seekers and Immigration Detainees,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40, no. 12 (2014): 1991–2009. ↵

- Charles Taylor, “Modern Social Imaginaries,” Public Culture 14, no. 1 (2002): 91–94. ↵

- Clifford Geertz, “Religious Belief and Economic Behavior in a Central Javanese Town,” Economic Development and Cultural Change 4, no. 2 (1956): 134–158. ↵

- Geertz, “Religious Belief.” ↵

- Griffiths, “Out of Time,” 1994. ↵

- Liviu Chelcea and Gergő Pulay, “Networked Infrastructures and the ‘Local’: Flows and Connectivity in a Post-Socialist City,” City 19, no. 2–3 (2015): 344–355, https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1019231. ↵

- Steven Graham, “Switching Cities Off,” City 9, no. 2 (2005): 169–194. ↵

- Caroline Humphrey, “Ideology in Infrastructure: Architecture and Soviet Imagination,” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 11, no. 1 (2005): 39–58. ↵

- Loïc Wacquant, Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2008). ↵

- Hillary Angelo and Christine Hentschel, “Interactions with Infrastructure as Windows into Social Worlds: A Method for Critical Urban Studies: Introduction,” City 19, no. 2–3 (2015): 306–312, https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1015275. ↵

- Nikita Besedovsky et al., “Time as Infrastructure,” City 23, no. 4–5 (2019): 580–588, https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2019.1689726. ↵

- Colin McFarlane and Jon Rutherford, “Political Infrastructures: Governing and Experiencing the Fabric of the City,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32, no. 2 (2008): 363–374. ↵

- Hillary Angelo and Craig Calhoun, “Infrastructures of the Social: An Invitation to Infrastructural Sociology,” April 2013. TS. NYLON Group, Berlin; Susan Leigh Star and Karen Ruhleder, “Steps Toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces,” Information Systems Research 7, no. 1 (1996): 111–134. ↵

- Jennifer Robinson, “Global and World Cities: A View from off the Map,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 26, no. 3 (2012): 531–554. ↵

- David Harvey, “Debates and Developments. The Right to the City,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27, no. 4 (2003): 939–941. ↵

- Harvey, “Debates and Developments,” 939–941. ↵

- Tauri Tuvikene et al., “Post‐Socialist Infrastructuring,” Area 52, no. 3 (2020): 575–582, https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12590. ↵

- Rodney Harrison, “Forgetting to Remember, Remembering to Forget: Late Modern Heritage Practices, Sustainability, and the ‘Crisis’ of Accumulation of the Past,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 19, no. 6 (2023): 579–595. ↵

- Anne-Kristin Pyburn, “Authentic Kyrgyzstan: Top-down Politics Meet Bottom-up Heritage,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24, no. 7 (2018): 709–722, https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1390489. ↵

- Michael Herzfeld, “Heritage and the Right to the City: When Securing the Past Creates Insecurity in the Present,” Heritage & Society 8, no. 1 (2015): 3–23, https://doi.org/10.1179/2159032X15Z.00000000035. ↵

- Charles Taylor, “Modern Social Imaginaries,” Public Culture 14, no. 1 (2002): 91–94. ↵

- John Allen, “Economics of Power and Space,” in Geographies of Economies, eds. R. Lee and J. Wills (London: Arnold, 1997), 143–165. ↵

- Griffiths, “Out of Time,” 1995. ↵

- Steven Feld and Keith H. Basso, eds., Senses of Place (Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 1996). ↵

- Griffiths, “Out of Time,” 1997. ↵

- Wolfgang Steinmüller, Riskante Netze: Informations- und Kommunikationstechnik zwischen Technologieabschätzung und Technik-Gestaltung (Wien/München: Oldenbourg, 1990). ↵

- Daniel Miller, Material Culture and Mass Consumption (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997); Daniel Miller, “Why Some Things Matter,” in Material Cultures: Why Some Things Matter, ed. Daniel Miller (London: UCL Press, 1998), 3–21. ↵

- Herzfeld, “Heritage and the Right to the City.” ↵

- Harvey, “Debates and Developments,” 939–941. ↵

- Johann P. Arnason, “Introduction,” Thesis Eleven 60, no. 1 (2000): v–vii, https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513600060000001. ↵

- Martin Heidegger, “The Question Concerning Technology,” from Basic Writings, rev. ed. (New York: HarperCollins, [1993] 2008), 311–341. ↵