1 Annotated Bibliography

Virginia Costello

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Understand the rhetorical basis of the annotated bibliography genre

- Conduct academic research drawing from multiple sources in multiple media

- Write paragraphs that describe, evaluate, and/or summarize sources

- Choose discipline-appropriate citation styles and citation managers

I. Introduction

The annotated bibliography comes in various forms and serves a variety of purposes. Thus, authors might include an annotated bibliography at the end of their text to offer further reading. Advanced students might be required to produce an extended annotated bibliography before they begin their dissertation. Professionals, such as those from the Bureau of International Labor Affairs and the U.S. Department of Labor, for example, might create an annotated bibliography to inform other scholars, policy-makers, and the general public: Addressing Labor Rights in Colombia. Or, more importantly for the purposes of this chapter, students might create an annotated bibliography at the preliminary stage of their research, as it serves as a foundation for a larger project, like a college-level research paper.

Writing an annotated bibliography helps researchers organize their sources and gain perspective on the larger conversation about their topic. It is a list of sources (or a bibliography) divided into two parts: The first part, the citation, contains basic information about the source, such as the author’s name, the title of the work, and the date of publication. The second part contains individual paragraphs that describe, evaluate, or summarize each source.

As you will notice in the examples in this chapter, the number and type of sources (e.g., books, scholarly articles, government websites) required for an annotated bibliography vary, as do the requirements for each paragraph. If your wider goal is to create an annotated bibliography for your dissertation committee, you may need eighty scholarly sources (e.g., peer-reviewed articles, books on theory related to your topic, or recent studies that evaluate data), each followed by an evaluative paragraph. If, however, you are a first-year college student enrolled in an introductory research class, your instructor may require you to find, say, seven specific types of sources: four scholarly articles, two primary sources, and a chapter in a book. Your instructor might ask you to write a simple summary paragraph for each source and then add a sentence about how you plan to use the source in a final research paper.

If you have written a research paper before, then, in all likelihood, you have also created a list of the sources you referenced in the paper. Depending on the style of citation required (e.g., MLA, APA, CMS), that list might have been called Works Cited, References, Endnotes, or, perhaps, Bibliography. Similar to these pages, citations in the annotated bibliography are often listed in alphabetical order according to the author’s last name. Although the order of the information about the source varies depending on which citation style you use, most of the basic information required, such as the author’s name, the title of work, and the date of publication, does not. Unlike those pages that only list sources, in the annotated bibliography, each citation is followed by a paragraph.

Example 1.1: Selection from a student paper in MLA format (8th Edition)

Prison Reform: Annotated Bibliography

Høidal, Are. “Prisoners’ Association as an Alternative to Solitary Confinement—Lessons Learned from a Norwegian High-Security Prison.” Solitary Confinement. Effects, Practices, and Pathways toward Reform, Eds. Jules Lobel and Peter S. Smith. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2020, pp. 297–309.

In his piece about the effects of solitary confinement, Høidal draws attention to the 17th Section of the Norwegian Penal Code. This section of the code states that all inmates should be allowed to work with others during daytime hours. Norway, the inspiration for many modern-day prison reformations, is globally recognized for taking excellent care of its prisoners, as opposed to other countries, such as the United States. In this chapter, Høidal discusses and evaluates Norway’s idea that prisoners should have access to the community both within and outside the prison system during daytime hours. He mentions that Norway offers educational programs for prisoners because it aligns with what Norway views as the purpose of prisons and Section 17 of the Norwegian Penal Code: to rehabilitate. Inmates are nourished both physically and mentally so that upon their release, they can return as functioning members of society. This nourishment, Høidal concludes, also lessens the likelihood of re-conviction.

Tønseth, Christin, and Ragnhild Bergsland. “Prison Education in Norway – the Importance for Work and Life After Release.” Cogent Education. vol. 6, no. 1, 2019, pp. 1-13, https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1628408

Tønseth and Bergsland delve into the complexity of Norway’s prison education system. Norwegian prisons have introduced a transformative learning theory, one that argues that providing education can promote change in the learner. After enabling inmates to obtain an education, researchers noticed an increase in self-determination, an increase in self-esteem, and several social benefits. Tønseth and Bergsland show that learning, especially in the prison system, is more than merely obtaining knowledge. A new, mentally stimulating environment is associated with learning in prisons, which promotes self-growth, something that is very important to the people running the Norwegian Prison System. Research on the effects of different methods of rehabilitation on inmates is still being conducted; however, according to the authors, there is already a promising trajectory.

In the example above, the student’s paragraphs include each source’s main points, some context, and an occasional evaluative adjective or sentence. Before you begin your assignment, carefully read or reread the assignment prompt from your instructor. If your assignment calls for descriptive and evaluative paragraphs, that means that you should discuss the strengths and weaknesses of your sources’ arguments. You might also complete basic background information on the author and then discuss the author’s credibility. Some assignments may ask you to discuss the source’s relevance in the larger conversation of that particular discipline and/or to discuss the types of sources the author references.

If your assignment calls for summary paragraphs, you should identify the main points of each source and write those points in your own words, employing transitions to help create a unified paragraph (rather than a list of ideas). Summary paragraphs do not include your own opinion or quotations from the text. Whether you are writing descriptive, evaluative, or summary paragraphs, the main purpose is to provide enough information about the source so that readers can determine if they want to read the original. After reading and annotating your sources and writing your paragraphs, you will have a clearer understanding of the arguments other scholars are making about your topic. This understanding will help you situate or contextualize your own argument in your research paper. (See section VI. Writing Strategies in this chapter for detailed examples.)

Many students think that research is a linear process: choose a topic, research the topic, write the research paper. But it can be more helpful and productive to think of the process in a much less linear and restrictive way. The sources you include in your annotated bibliography, the first stage of your research, may not be the same as those you include in your final paper. In fact, as you narrow your focus, read more sources and allow your ideas to change, you will find yourself eliminating sources that are too broad, too narrow, or tangential to your focus. Your search for new sources should continue throughout the writing process. In other words, as mentioned in the introduction, and as you will see in this and other chapters of this text, the research process is complicated (and interesting) and, at some stages, nearly cyclical: the research you do informs the research you are going to do and re-situates the research you have completed.

Practical Guidelines and Considerations

Once you have a general understanding of the purpose and format of the final product, the annotated bibliography, you should thoughtfully choose your topic within the parameters of your assignment; choosing your topic is the beginning of your research.

Here is a simplified list of steps for developing your annotated bibliography, with names of sections in this chapter that provide more detail.

- Choose a topic and, if your instructor requires it at this stage, develop a research question. (In this section, below)

- Briefly consider the purpose and style of the assignment (II. Rhetorical Considerations)

- Create keywords and plug them into library databases or other search engines. (IV. Research Strategies)

- Choose appropriate sources from the database/search engine results. Read and annotate those sources. (IV. Research Strategies and V. Reading Strategies)

- Use your annotations on your sources to write evaluative, descriptive, or summary paragraphs. (VI. Writing Strategies)

- Choose a citation manager, identify an appropriate citation style, and alphabetize citations and paragraphs. (III. The Annotated Bibliography Genre Across Disciplines)

Introductory research classes often offer a theme and require students to narrow their focus by choosing a topic within that theme. If your class offers a theme, you might narrow your focus by thinking about the topic through the lens of your major. Thus, for example, if your class has a theme such as prison reform and your major is architecture, you may wonder what architects consider as they build new prisons, or you might compare prison architecture in different countries, like the U.S. and Norway.

North Carolina State University Libraries offers this video, which might help you choose a topic.

Library Referral: Topic Development and Your Personal Angle

(by Annie R. Armstrong)

It might be tempting to ask someone, “What’s a good research topic?” While discussing possible topics with your classmates is a good idea, in the end, you should be the one providing that answer. Your personal investment in a topic can propel you through the thorniness of the research process. If your course has a set theme (e.g., sustainability, stand-up comedy, censorship, prison reform), consider your personal angle: what passions, interests, or causes excite you, and how might they be related to this theme?

Even if you say “cats,” or “video games,” you’ll be able to make a connection to the course theme that intrigues both you and your reader. There are always larger questions you can ask about these interests. For example, if you love cats: are you more broadly concerned with animal welfare? If your passion is video games: to what degree do you think they help or hinder the social lives of teens? Think about how you can “zoom in” or “zoom out,” to focus on both broad and narrow aspects of your topic.

Discuss your topic with a librarian to unearth new ideas and connections, and watch the video One Perfect Source? for an explanation of how to find sources for a topic.

Developing a Research Question

Some instructors may ask you to develop a research question before you begin your annotated bibliography. Others may instruct you to develop it in the proposal stage (see Chapter 3). In either case, at some point in the early stages of research, you will need to write a question that guides your research. It should be one that is focused, complex, and genuinely interests you. Writing the research question will help you narrow your focus and create keywords. The more time and thought you put into creating this question now, the easier it will be to complete your research and write the paper later.

Example 1.2 Here are a few student examples of research questions.

- In what ways might the U.S. look to the Norwegian prison system as a model for prisoner rehabilitation?

- To what extent can the U.S. incarceration system be reformed to be more cost-effective while at the same time helping prisoners undergo significant rehabilitation?

- How has the reintroduction of wolves into the Yellowstone region affected the livelihood of cattle ranchers in the region?

Notice that these questions avoid a simple either/or binary (e.g., either we look to Norway for answers or we don’t). Language such as “in what ways” and “to what extent” open up the possibility of a range of answers.

While the answers to these questions will include factual, verifiable evidence (e.g., the kinds of rehabilitation programs the U.S. offers, the number of prisons in the U.S.), the questions themselves do not for ask for simple, factual answers. A factual question does not make a solid research question because it doesn’t present information upon which reasonable people might disagree, and it is easily answered. (Here is an example of a factual question, not a research question: How much does it cost to maintain the U.S. prison system? The question asks for a number, not a thoughtful argument.)

One way to begin writing the research question is with a timed writing exercise like the one below.

Write or type your topic at the top of a piece of paper or document. Set a timer for exactly six minutes. Once the timer begins, allow yourself to write every question that comes to mind about your topic, even if it might seem somewhat off-topic, mundane or simplistic. In other words, don’t censor yourself, and don’t worry about spelling or typos. When you think about your topic, what aspect of it makes you curious? You might start with how or why questions. Turn whatever comes into your head into a question. Continue writing for the entire time, even when your mind wanders and gives you a sentence like, “I don’t know what to write.” Turn it into a question: “I don’t know what to write?” Doing so keeps your mind moving and your handwriting. More importantly, it often helps you move on to a new idea.

When the time is up, read and categorize your questions. First, underline the factual questions. You may want to find the answers to those questions, but they are not research questions. Second, strike through the mind-wandering questions. Examine what you have left. Any question strike you? Can you develop a research question by combining the simple questions and adding, “to what extent,” or, “in what ways”? Remember that this is a draft research question and that you may revise it as you find more information about your topic.

In general, your research question should guide your exploration of your topic rather than lead you to a preconceived answer or a belief you already hold. For example, if your topic is prison reform and you think private prisons are morally or ethically problematic, consider sources that take a variety of positions, not simply ones that point to what you already believe. Leave your mind open to finding sources that explain the complexities of the prison system, including reasons that states have relied on private prisons (such as relieving overcrowding issues). In other words, don’t avoid sources that seem to contradict or complicate your current position. When you read arguments that you find problematic and consider evidence that might not support your original ideas, you develop a wider understanding of your topic. Grappling with arguments that challenge your own ideas expands your ability to understand, address, and perhaps refute points and shows that you understand the larger conversation about your topic.

In short, let the research inform your position.

Note that this doesn’t mean you should suddenly change your position. It does mean that just as you do in a reasonable conversation, you should consider views and values other than your own. Then you reevaluate, modify, and/or fortify your original position.

More Resources 1.1: Research Questions

Here’s a link with more tips about How to Write a Research Question.

II. Rhetorical Considerations: Purpose and Style

Whether you are writing an annotated bibliography for a biology or anthropology class, a grant application, or a section at the end of a book, you will want to consider the purpose and style of your work. If you are writing your annotated bibliography for a class, identify the parameters of the assignment and consider a few questions:

- Who is the intended audience?

- How many and what kind of sources do you need? (e.g., scholarly articles, books, government websites)

- What citation style will you use? (e.g., AMA, APA, CMS, MLA)

- What types of paragraphs should you write? (e.g., evaluative, descriptive, summary, or some combination)

In answering the last question, remember that some instructors will ask you to simply summarize each source. Others may want a summary and a sentence about how you will use each source, or a sentence that explains how each source will help you answer your research question. Still other instructors will ask for descriptive or evaluative information about your sources. You can find examples and further discussion of these types of paragraphs in the VI. Writing Strategies section of this chapter.

III. The Annotated Bibliography Genre Across Disciplines

Briefly examine the following annotated bibliographies written by academics and other professionals. These examples will provide you with a greater understanding of how your work in the classroom translates to the work in the profession. The first example, written by Professor Sue C. Patrick and published on the American Historical Association website, centers on primary sources and is part of a larger project: Annotated Bibliography of Primary Sources | AHA.

Primary sources, which will be discussed in greater detail in the IV. Research Strategies section of this chapter, are those from a first-person perspective or a direct piece of evidence (e.g., constitutions, eyewitness accounts, diaries, letters, raw data). After each citation, Patrick provides an explanation of how she used the source as a part of a writing project for her students. If you navigate to the contents page of Patrick’s original project, you will see that this annotated bibliography is one small part of her project. The larger project offers a wide range of information for history instructors: Teaching Difficult Legal or Political Concepts: Using Online Primary Sources in Writing Assignments | AHA.

The second example, Parental Incarceration and Child Wellbeing: An Annotated Bibliography, focuses on quantitative research, which means that it centers around secondary sources. The author, Christopher Wildeman, professor of Policy Analysis and Management (and Sociology) at Cornell University, categorizes and summarizes studies that address the effects of paternal and maternal incarceration on children. In his summary paragraphs, Wildeman includes the data and final results of each study. Notice that he does not evaluate the information. Notice, too, that rather than listing all sources in alphabetical order, as students are generally required to do for their annotated bibliography, this author divides his annotated bibliography into sections, and each of those sections are in alphabetical order.

Example 1.3: Academic and Professional Examples

In order to provide context and to help you make connections between the work you complete in your classes and the work professionals do, examine a few more annotated bibliographies in this Box Folder. You will notice these annotated bibliographies include a wide range of citation styles, sources, and summary, description, or evaluation paragraphs.

These examples are meant to show you how this genre looks in other disciplines and professions. Make sure to follow the requirements for your own class, or seek out specific examples from your instructor in order to address the needs of your own assignment.

Citation Styles

You may have noticed that in the annotated bibliographies linked above, the authors organized their source citations differently. The following video offers an introduction to citation styles.

Academic disciplines use different conventions for the style, placement, and format of their citations. You will find a few examples in the purple box below. It’s a good idea to become familiar with the citation style that professionals in your discipline use. For example, if you are premed, you may want to read the American Medical Association or AMA style guidelines. (Note that in-text citations which appear in the text of a research paper itself—rather than as a list—will be covered in Chapter 4.)

Example 1.4: Examine the following examples of two sources cited in four different styles. What do you notice about the similarities and difference between these styles? What does your comparison tell you about the priorities of those who developed these styles?

AMA (American Medical Association)

Black B. The character of the self in ancient India : Priests, kings, and women in the early Upanisads. Ithaca: State University of New York Press; 2007. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uic/detail.action?docID=3407543.

Costello JF & Fisher SJ. The Placenta – Fast, Loose, and in Control. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385(1):87-89. doi:10.1056/NEJMcibr2106321

APA (American Psychological Association)

Black, B. (2007). The character of the self in ancient India : Priests, kings, and women in the early Upanisads. Ithaca: State University of New York Press. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uic/detail.action?docID=3407543

Costello, J. F., & Fisher, S. J. (2021). The placenta — fast, loose, and in control. The New England Journal of Medicine, 385(1), 87-89. doi:10.1056/NEJMcibr2106321

CMS (Chicago Manual of Style)

Black, Brian. 2007. The Character of the Self in Ancient India : Priests, Kings, and Women in the Early Upanisads. Ithaca: State University of New York Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uic/detail.action?docID=3407543.

Costello, Joseph F., and Susan J. Fisher. 2021. “The Placenta — Fast, Loose, and in Control.” The New England Journal of Medicine 385 (1): 87-89. doi:10.1056/NEJMcibr2106321

MLA (Modern Language Association)

Black, Brian. The Character of the Self in Ancient India : Priests, Kings, and Women in the Early Upanisads. State University of New York Press, Ithaca, 2007, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uic/detail.action?docID=3407543.

Costello, Joseph F., and Susan J. Fisher. “The Placenta — Fast, Loose, and in Control.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 385, no. 1, 2021, pp. 87-89, doi:10.1056/NEJMcibr2106321.

Behind each style of citation is a logic that is connected to the discipline. Professional groups from each discipline create these styles that reflect the values of that discipline.

AMA, for example, emphasizes collaboration among researchers, and so articles are often discussed with and written by more than one scholar. The titles of the journals are abbreviated, as readers are expected to know those names. Here are general guidelines for AMA General Style.

APA style citation begins with the author’s last name and first initial, followed by the year of publication in parenthesis. APA professionals are social scientists, and thus emphasize the date of publication because it is more important when something is published than, say, where it was published. When readers skim a list of citations in APA style, they can quickly see how the focus of the research has changed over the years. Here are general guidelines for APA General Format.

CMS incorporates two systems. Purdue OWL describes these as “the Notes-Bibliography System (NB), which is used by those working in literature, history, and the arts. The other documentation style, the Author-Date System, is nearly identical in content but slightly different in form and is preferred by those working in the social sciences.” Here are general guidelines for CMS General Format.

MLA is more often used in the humanities; it emphasizes the full name of the author and thus the creativity or individuality of the writer. The date of publication appears toward the end of the citation. Here are general guidelines for MLA Format and Style.

Although we are only addressing styles of citations for the purpose of creating an annotated bibliography, these styles also require a specific document format. So, for example, if you are writing a research paper in APA style, you may use section headings, place page numbers in the upper righthand corner of every page, and title your citations page “References.” MLA style requires a header with your last name, a space and the page number on every page (except the first), and the citation page is called “Works Cited.”

Citation Management Tools

Citation management tools help keep your research organized and create individual citations as well as bibliographies in the proper style for your discipline. Your library may offer programs such as RefWorks or EndNote or provide links to open-source programs such as Zotero. If you want help deciding which tool is best for your project, click here: How to Choose a Citation Manager.

These tools are useful, but you will still want to understand the basic conventions of the citation style that you are using so that you can spot errors. Proofread carefully. Stick to one style of citation and do your best not to confuse it with another style—something that is easy to do if, for example, you are reading articles that use APA style, but you are writing in MLA style. Note also that the styles change with each new handbook edition. So for example, the most recent MLA Handbook (9th edition) was updated in 2021. Fortunately, Zotero and other citation mangers will offer you an option of not only style, but also edition (e.g., MLA 8th or 9th edition).

IV. Research Strategies: Finding, Identifying, and Using Sources

Before you begin your library research, list at least seven keywords or phrases. These are words that describe your topic. Your list might begin with the most basic nouns (e.g., prison, mental health) and then become more personalized and specific (e.g., mass incarceration, schizophrenia). If you have written a research question, identify the keywords in that question. List the nouns and verbs and then find synonyms.

More Resources 1.2: Search Strategies

The following video offers suggestions on how to use keywords in your research question to create more keywords: Savvy Search Strategy

Here’s another short video on searching databases using Boolean logic: How Should I Search in a Database?

Types of Sources

Your instructor might require you to find sources from general categories, like primary or secondary sources. Alternatively, she might outline something more specific, such as peer-reviewed articles, ebooks, interviews, or book reviews. A few categories worth recognizing at the onset of your research include primary vs. secondary sources, popular vs. scholarly sources, and peer-reviewed journals and articles. Whatever your requirements, you should be choosy about your sources; do not simply settle for the first ones you find. Skim or read the sources before you count on them to help you develop your argument. Don’t be afraid to reject a few. Research is a process, and not every search will yield good results. Furthermore, if you simply accept all the sources you find on your first keyword search, you may have problems tying things together later.

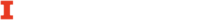

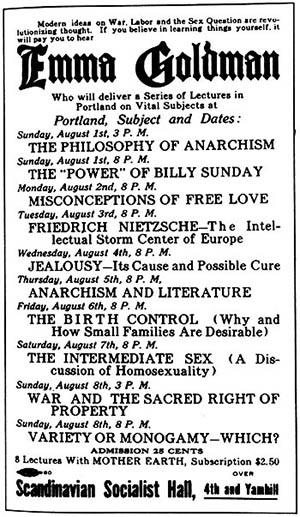

Primary sources are those that offer firsthand accounts, like witness statements from an accident or crime, diaries, personal letters, interviews, photographs like the one of Ida B. Wells-Barnett and her son Charles, or flyers like the one that lists lectures Emma Goldman gave in Portland in 1915 (see Figure 1.2 and Figure 1.3 below).

A secondary source analyzes a primary source or other secondary sources. The image of the campaign card in Figure 1.4 is a primary source, but when a scholar writes and publishes an analysis of this source and refers to other sources that, say, describe the Republican Party principles as outlined in 1928 and why Wells-Barnett wanted to be a part of the party, then that analysis (the scholar’s work) becomes a secondary source.

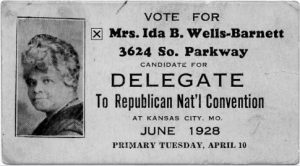

When you are trying to determine if a source is primary or secondary, pay attention to the author’s language. For example, examine Jessica Dillard-Wright’s abstract below.

Here’s the text for the entire abstract:

In the middle of the paragraph, she states, “I draw on anarchist, abolitionist, posthuman, Black feminist, new materialist and other big ideas to plant seeds of generative insurrection and creative resistance.” In this sentence, the writer points out how she builds her argument and analysis on the work of others, meaning that it is a secondary source. Another clear indication that this is a secondary source lies in the bibliography. Here’s a selection from the first page of Dillard-Wright’s citations.

Ashley, J. A. (1980). Power in structured misogyny: Implications for the politics of care. Advances in Nursing Science, 2(3), 2–22.

Benjamin, R. (2018). Black afterlives matter: Cultivating kinfulness as reproductive justice. In A. Clarke, & D. Haraway (Eds.), Making kin not population (pp. 41–66). Prickly

Paradigm Press.

Benjamin, R. (2020). Black skin, white masks: Racism, vulnerability, and refuting blackpathology. Department of African American Studies. https://aas.princeton.edu/news/black-skin-white-masks-racism-vulnerability-refuting-black-pathology

Braidotti, R. (2020). “We” are in this together, but we are not one and the same. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 17(4), 465–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10017-8

Butler, J. (2002). Is kinship always already heterosexual? Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 13(1), 14–44.

Chinn, P. (2020, May 21). Nursing in the Anthropocene. Advances in Nursing Science Blog. https://ansjournalblog.com/2020/05/21/nursing-in-the-anthropocene

Choy, C. (2003). Empire of care: Nursing and migration in Filipino American history. Duke University Press.

Connolly, C. A. (2010). “I am a trained nurse”: The nursing identity of anarchist and radical Emma Goldman. Nursing History Review, 18, 84–99.

Davis, A. Y. (2020, October 6). Why arguments against abolition inevitably fail. Medium. https://level.medium.com/why-arguments-against-abolition-inevitably-fail-991342b8d042

Although the difference between primary and secondary sources may seem obvious now, consider this complication. On one hand, a recent article from a newspaper may be considered a secondary source, as the reporter might have talked to witnesses or other people involved. On the other hand, a newspaper article from 1920 might be considered a primary source because it provides a historical perspective.

Popular vs. Scholarly Sources

A scholarly source employs technical or discipline-specific language, is written for a narrow audience (specific scholars), and always includes a bibliography or list of sources. A popular source is one that employs more accessible language, appeals to a wider audience, and often includes photos or images.

Most instructors will require you to use library databases to find sources, but may allow you to use search engines such as Google or Google Scholar later in the course, when you have a clearer understanding of the wider conversation around your topic and how you might use these sources. Academics (and the greater educated world) consider sources found in the library databases or through the library search box as reliable and credible. They also recognize that rather than a simple line between reliable and unreliable sources, there is a spectrum, which simply means that some sources are more credible than others.

For example, some academics consider peer-reviewed journals such as The Prison Journal more credible than popular sources such as Psychology Today, both of which are available through many academic library databases. Articles published in The Prison Journal undergo a rigorous peer review process, which means that a variety of experts in the field read and comment on a draft of the article. Often, the writer has to revise and resubmit the draft before the editor approves it and the final article is published. Articles published in Psychology Today are written by authorities on a particular subject but do not go through a peer-review process. Generally, editors are the only ones that read submissions to determine if they are worthy of publication. Although the process of publication is different, both types of articles offer valuable and useful research.

In general, we accept that sources found through library search engines and databases are reliable; they are worthy of thoughtful consideration and analysis. There are many sources found outside the library that are reliable, too, but determining the reliability of the source becomes more of a challenge. Here are questions to consider when evaluating the reliability of a source:

- What’s the writer’s purpose in creating the source? Is the source meant to entertain, provide news, or both? Is it meant to educate, persuade, scandalize, or sell a product or service, or does it have a different purpose altogether?

- Is the source built on credible sources? (Check the credibility of the sources in the bibliography.)

- Is the author an authority on the subject? Does the author refer to other authorities? (Check the author’s background and experience.)

- Does the source provide verifiable evidence and facts to support claims?

More Resources 1.3: Questions for Analyzing Sources

Library Referral: Searching is Experimental

(by Annie R. Armstrong)

Think of searching library databases and catalogs as an experiment rather than a linear process. It may get messy and lead you in unexpected directions. The databases can’t interpret natural language, so you’ll need to boil your topic down to a few keywords. See the Choosing Keywords video for a full illustration of this process.

Your first search won’t be your last! Experiment with different keywords and gather more sources than you think you’ll actually need. Once you start reading and learning more about your topic, you may discover that some of your sources are only tangentially connected to the direction in which you want to take your topic.

The focus of your research changes as you become more knowledgeable about the topic.

Searching a variety of research databases and catalogs will open the door to a broader range of viewpoints from different academic disciplines and publication types (think books, book chapters, scholarly/peer-reviewed journals, newspapers, and popular/mainstream magazines).

Library Databases

Once you know what kind of sources you need for your assignment (e.g., primary or secondary, popular or scholarly) and you have a list of keywords, examine library databases. Libraries buy subscriptions to two basic types of databases: general or multidisciplinary (e.g., JSTOR, Academic Search Complete, ProQuest) and subject-specific (e.g., Psycinfo, AccessAnesthesiology, Embase, Excerpta Medica). Unlike Web-based searches, library databases offer quality controls. Articles have been reviewed by professional editors and fact-checked before they are published in academic journals. Database companies, like JSTOR, buy subscriptions to these journals, organize, and categorize them.

For introductory research courses, you will want to start with the general and multidisciplinary databases. Plug your keywords into the database search box. Skim the titles for appropriate sources. As you progress and find more information on your topic, you may want to use the subject-specific databases.

As you are researching your topic, pay attention to the types of sources you find. If your source is from the New York Times, for example, is it a news story or an opinion piece? If it’s a video, is it a documentary or a TED Talk? What difference does the type of source make? The answer to this question depends, in part, on how you will use the source. Will you use a source as background information or evidence to support your argument? Will you use the source to present a claim that opposes your argument and then refute that claim by providing factual or authoritative evidence? You may not know how you will use a source when you first find it, but it’s worth thinking about the different ways a source can be put to use. See Chapter 4 for more about how to use sources once you start writing your research essay.

Finding More Keywords

After you type the keywords in library search boxes or databases, you may need to narrow or expand your search, depending on your results. If your topic is prison reform, for example, you will need to choose an angle. Start by asking questions about your topic, and think about choosing a lens through which to view your topic. Even if it seems obvious, start with the basics: What do you know about your topic? Can you use something you already know about or have an intense interest in as a lens through which to view your topic?

For example, if architecture students are interested in this topic, they might ask questions about what the architecture of U.S. prisons tells us about how we understand punishment and rehabilitation. When you find a scholarly article worth reading, examine the list of words under the headings Keywords, Subject, or Author’s Key Terms and look for more words to add to your own list.

In the example above, the list of keywords appears below the abstract: “ethical prison architecture, prison design, carceral geography, environmental psychology, prisoner wellbeing, prison climate.” While architecture students may have searched databases with keywords like “prison architecture” or “prison design,” they may not have thought of “carceral geography,” a phrase worthy of another database search.

Beyond the Library: Sources on the Web

Thus far, we focused on finding sources through academic or public library databases. For a wider search that includes reliable sources which may not be available through the library, such as an organization’s website (e.g., The Marshall Project which collects articles published about the prison system), use common search engines such as Google, Yahoo!, or Bing. These search engines use algorithms based on popularity, previous searches, commercial investment, location, and relevance, rather than on keywords and combinations of keywords, like library databases. This means that you will want to approach these sources with a healthy dose of skepticism: Double-check facts (see links to fact checkers in the last part of this section) and ask questions about the people, organizations, corporations, or businesses behind the sources you find using common search engines.

Generally, .com or commercial sites do not consistently offer information suitable in length, breadth, or reliability to be referenced in a research paper. The major exception to this rule is reliable newspapers like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Guardian. Reliable news outlets may report on a groundbreaking discovery from NASA and will explain that discovery in terms a non-expert will understand, but they will also provide a link to the study so that an expert (or a researcher like you) can examine the original.

If you want to save yourself the frustration of sifting through many .com sites, try searching domains that end in .edu. In the Google search box, type Site:edu and then add a keyword or phrase, like “prison reform.” Thus, you would write, Site:edu prison reform. You can also use this formula for sites ending in .gov or .org. These three domains tend to offer more credible information than .com, but, again, you should critically analyze the websites rather than simply accepting the information as accurate. Evaluate the source by asking questions like those listed in the previous section.

If you want to go in a different direction, search for websites that professionals in your discipline use and search the bibliographies posted there. For example, professionals in the life sciences use bioRxiv, a free online archive and distribution service for unpublished manuscripts. It’s a place where professionals deposit their papers for comments before they submit them to journals for publication.

Social Media

While you would not want to use information on social media to support an argument you are making in an academic research paper, the effect and use of these outlets might be worthy of note. Thus, for example, you might ask about the patterns of use of social media like Twitter. Tweets offer fragments of ideas, and they are not particularly useful when you are writing a research paper, but if social scientists collect these primary sources, they might notice patterns that tell us something about politics and culture. More generally, they might study tweets and their influence on how and what people think. The Pew Research Center (https://www.pewresearch.org), a nonpartisan, non-advocacy group, collects and analyzes tweets.

Checking for Accuracy: Here’s the Principle

That Beyoncé tweeted something in particular is easily certifiable by finding the tweet in which she made the claim. However, consider a separate question: Is what Beyoncé said true? This is the more difficult question to answer, as you need to find verifiable evidence. You will need to look for evidence that is an authoritative confirmation of a claim. Authoritative confirmation means that someone, or better yet several someones, in authority on the subject support the claim and perhaps offer data, statistics, or facts.

Beyoncé may have millions of followers, and thus what she tweets influences what her followers think, but does that make what she says accurate or factual? No, of course not. She may be an expert in making music, but she is not an expert in all things. She clearly influences people, and that is worthy of note if your research question asks something about how social media influencers gain popularity.

If you come across information that you are not sure is accurate, whether you found it in a scholarly source or on a website, use a reliable fact checker, like the ones listed below, and find out what the experts say.

More Resources 1.4: Assessing Sources

V. Reading Strategies: Skim, Annotate, Summarize, and Evaluate

When you find a source that looks interesting, skim, don’t read it (yet). Because we are wary of the message it sends to students, some instructors hesitate to admit that skimming is a valid reading and research tool. Skimming allows you to search through many resources in a short amount of time and is a generally acceptable method of determining whether a source is appropriate for your project.

When you are searching for sources on the library databases, skim article abstracts, as they offer a short summary of the argument in the paper. Also skim introductions, headings, conclusions, and citation pages. Skimming is not, of course, a substitute for thoughtfully reading your sources before you begin writing your final paper. Here’s a helpful video on how to read a scholarly article:

More Resources 1.5: Reading Scholarly Articles

Notice that the scholars interviewed in “How to Read a Scholarly Article” all start by skimming the abstract and then, if the source seems appealing and appropriate, they read the abstract but also still skim (or skip altogether) other sections of the article.

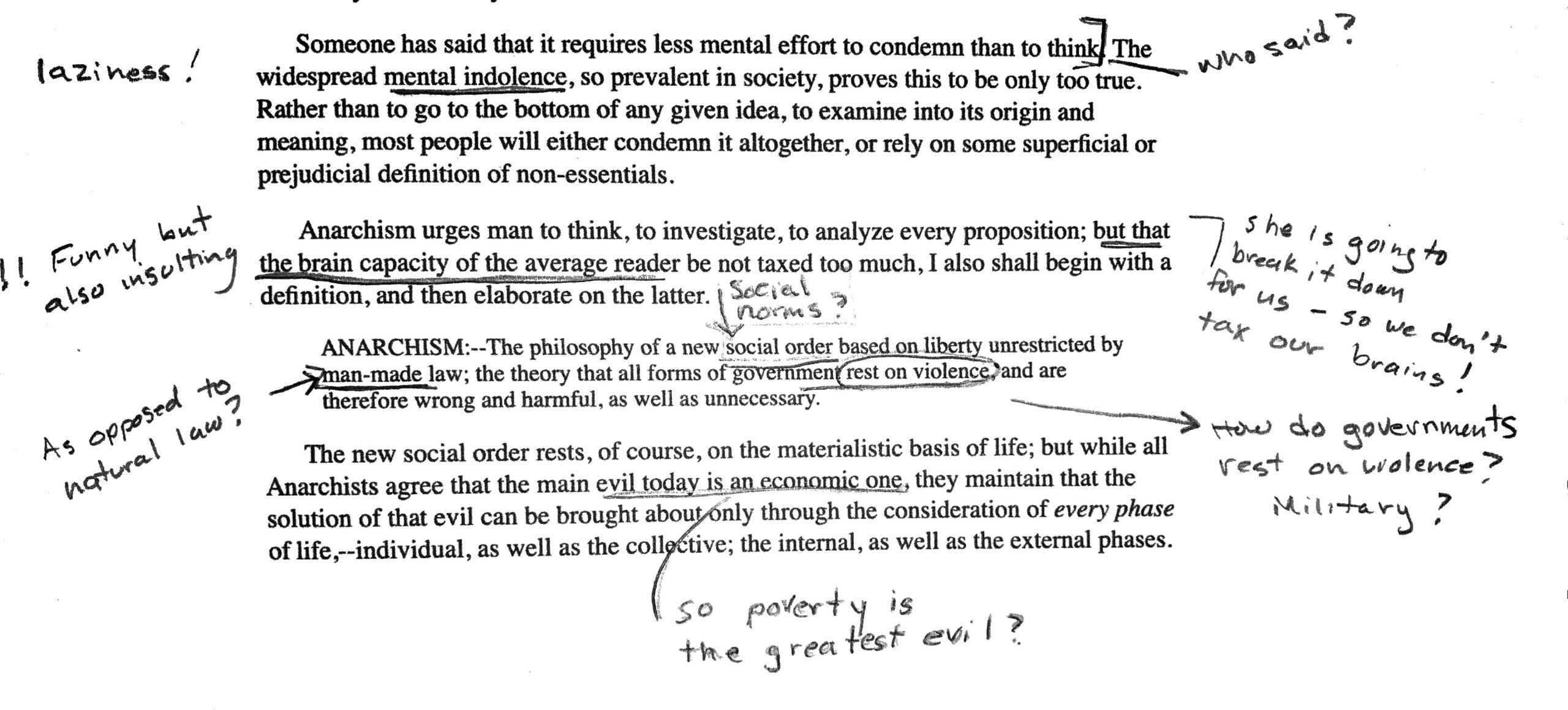

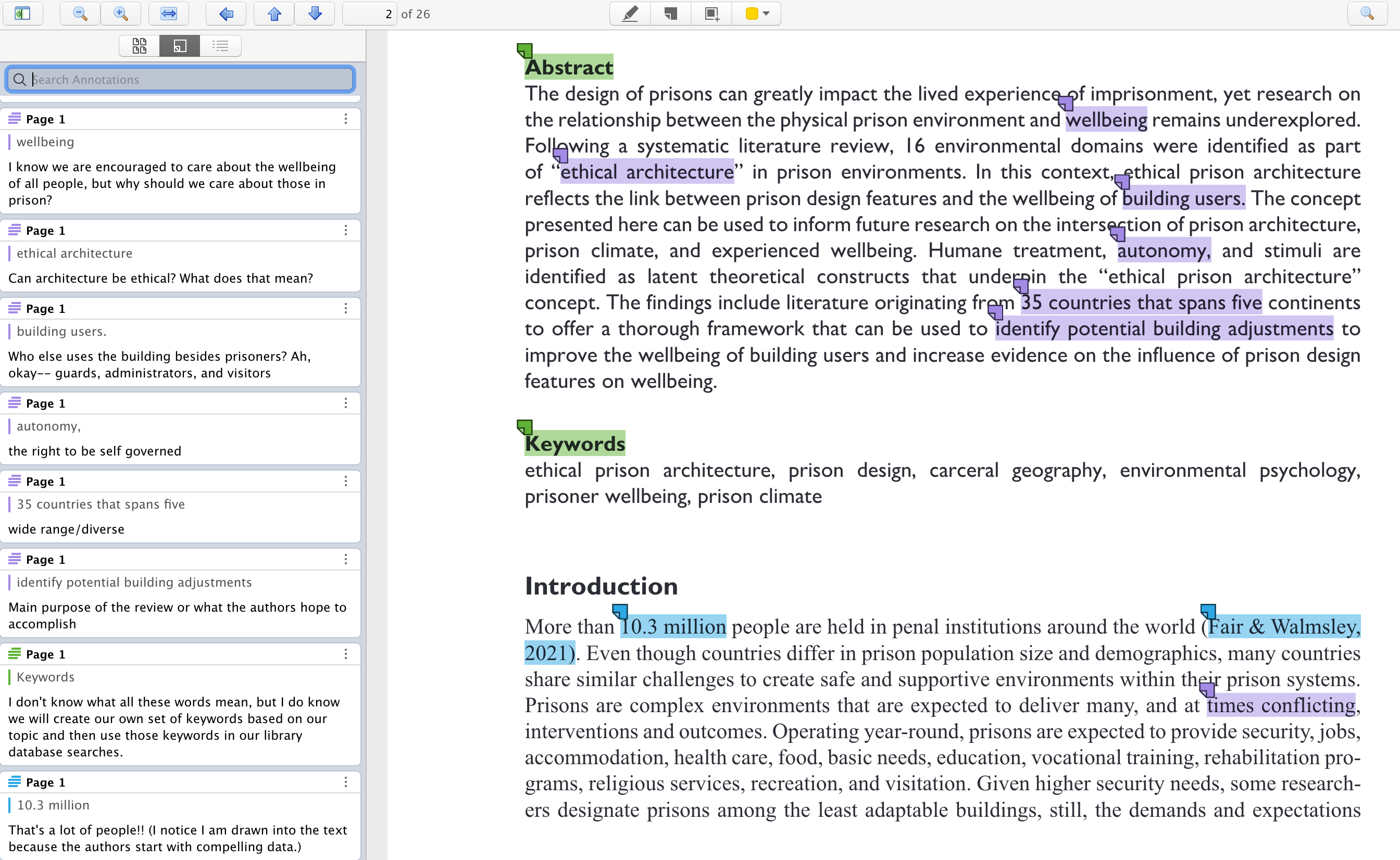

Some instructors will expect you to have read and annotated all of your sources before you draft your annotated bibliography assignment. Annotating, in this context, means marking up the text by underlining or paraphrasing important points, commenting on claims the author makes, or asking questions of the text. The word “annotated” that modifies the word “bibliography” refers to the paragraphs that are written based on the comments or annotations you made on each source.

Examine the annotations below. You may want to use the standard pen-and-paper method and write on the text itself (Figure 1.7), or you may want to use programs or apps such as Adobe, Diigo, or Notability to annotate a text electronically (Figure 1.8).

Annotating Video and Visual Sources

Traditionally, students annotate documentaries by simply taking notes with pen and paper. They keep track of important points and the times when those points occur. So, for example, in the video Anatomy of a Scholarly Article | NC State University Libraries mentioned in the previous section, you might pause the video and note the time that the important point occurs. For example, at 1:32 (one minute and thirty-two seconds from the beginning of the video), the speaker defines an abstract of article, so your notes might look like this:

1:32: An abstract is a summary of the article, usually under 150 words

More recent and sophisticated ways of annotating videos include downloading software programs that allow you to take notes directly on a video—a TED Talk video posted on YouTube, for example. Some programs allow you to use a split screen to watch the video, take notes on a document, and link those notes to specific parts of the video. Others, like YiNote and Transnote, allow you to take time-stamped notes while watching videos.

VI. Writing Strategies: Turning Annotations into an Annotated Bibliography

The annotations you have written on your sources become the fodder for the descriptive, evaluative, or summative paragraphs you need to write after each citation in your annotated bibliography.

Let’s look at a few specific examples and explore the style and tone of each. The descriptive and evaluative (also called “annotated”) are probably the most common, so we will start here. This paragraph might provide some background information on the author, place the author’s argument in the context of the field or discipline, and evaluate the claims and evidence provided in the source.

Example 1.5: Here’s an annotated example with an MLA style citation from The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign library guide.

The first sentence in italics and yellow highlight summarizes the argument. The bolded and blue highlighted phrases offer an evaluation, and the underlined and orange highlighted phrase identifies the larger conversation in that discipline.

Gilbert, Pam. “From Voice to Text: Reconsidering Writing and Reading in the English Classroom.” English Education, vol. 23, no. 4, 1991, pp. 195-211.

Gilbert provides some insight into the concept of “voice” in textual interpretation, and points to a need to move away from the search for voice in reading. Her reasons stem from a growing danger of “social and critical illiteracy,” which might be better dealt with through a move toward different textual understandings. Gilbert suggests that theories of language as a social practice can be more useful in teaching. Her ideas seem to disagree with those who believe in a dominant voice in writing, but she presents an interesting perspective.

Example 1.6: Here’s an example of an APA style (7th edition, 2019) citation and a slightly different evaluative paragraph from the Cornell Libraries.

The first sentence offers a little background information on the authors. The bulk of the paragraph is italicized and highlighted yellow to show where it summarizes the authors’ hypothesis and the results of their findings. The last line in this paragraph is underlined and highlighted orange to show where it makes a comparison to another study. This sentence shows that the writer is aware of the larger conversation happening in this discipline. Other paragraphs might focus more on the author’s credentials (degree, employment, experience), author’s reliability, and main points of the source.

Waite, L., Goldschneider, F., & Witsberger, C. (1986). Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review, 51, 541-554.

The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living.

Example 1.7: For comparison, here’s the same citation in MLA style, 8th edition.

Waite, Linda J., et al. “Nonfamily Living and the Erosion of Traditional Family Orientations Among Young Adults.” American Sociological Review, vol. 51, no. 4, 1986, pp. 541-554.

Example 1.8: Finally, here’s an example of a paragraph that primarily summarizes and then indicates how the student plans to use the source in the final paper.

The first sentence is underlined and highlighted orange to show the conversation and what the author is arguing against. The middle sentences are italicized and highlighted yellow to show where the author summarizes the main points of the chapter, and the final sentence is bolded and highlighted blue to show how the student will use this source in the final paper.

Thorp, Thomas. “Thinking Wolves.” The Philosophy of the Midwest. Eds. Josh Hayes, Gerard Kuperus, and Brian Treanor. Routledge, 2020. pp. 71-89.

Thorp claims that philosophers and scientists, motivated by a desire to increase our care and respect for non-human animals, have begun to question all of the traditional distinctions between humans and other animals. Beginning with a political analysis of the attitudes of western ranchers toward the return of wolves to the Yellowstone region, Thorp argues that our human reasoning is importantly and essentially different from animal cognition, for example, what wolves do when they hunt. He concludes that only humans have the capacity to be truly responsible for our choices, including our choices about how to care for the natural world. This source offers a foundation on which I will build my argument about the cognitive differences between animals and humans.

Example 1.9: More Samples

Whatever your discipline or particular assignment, remember that the best annotated bibliographies build their own credibility by referring to the credibility of their sources.

Key Takeaways

- Before you dive into the research, identify the parameters of your assignment and examine a model or example.

- Use the lens of your interests or academic discipline to choose a relevant topic.

- Create keywords and plug them into library databases or other search engines.

- Sift through the results and allocate time to read (or skim) and annotate sources.

- Use your annotations to write paragraphs that evaluate, describe, or summarize each source.

- Choose a citation manager and identify an appropriate citation style.

- Alphabetize and/or categorize citations and paragraphs.

References

Chicago Manual of Style 17th Edition. Chicago Manual of Style 17th Edition – Purdue OWL® – Purdue University. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2022, from https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/chicago_manual_17th_edition/cmos_formatting_and_style_guide/chicago_manual_of_style_17th_edition.html?edu_mode=on

Dillard-Wright, J. (2021). A radical imagination for nursing: Generative insurrection, creative resistance. Nursing Philosophy, 23, e12371. https://doi-org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1111/nup.12371

Davis, B. W. (2021). Zen pathways : An introduction to the philosophy and practice of Zen Buddhism. Oxford University Press, Incorporated.

“Emma Goldman Lectures in Portland, Oregon, August 1, 1915.” Jewish Women’s Archive. https://jwa.org/media/handbill-advertising-group-of-lectures-by-goldman-in-portland-oregon

Fosslien, Liz. (2022). What We Think. https://www.fosslien.com/

Mueller, S. (2005). “Documentation styles and discipline-specific values,” The Writing Lab Newsletter. Vol. 29, No. 6, pp. 6-9.

Patrick, S. C. “Annotated Bibliography of Primary Sources. Teaching Difficult Legal or Political Concepts: Using Online Primary Sources in Writing Assignments.” American Historical Association. https://www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/teaching-resources-for-historians/teaching-and-learning-in-the-digital-age/the-history-of-the-americas/teaching-difficult-legal-or-political-concepts/annotated-bibliography-of-primary-sources

Wells, I. B. Campaign card of anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett to be a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1928. Credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-08621, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.