2 Proposal

Jeffrey Kessler

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Understand the rhetorical basis of the proposal genre

- Identify specific ways to appeal to your audience

- Explore a topic in order to plan and propose your research project

- Use metadiscourse in your writing to explain your research plan

I. Introduction

The proposal is perhaps the most common genre you will encounter outside of the composition classroom, and the most varied one. In its simplest definition, a proposal is a suggested plan. Whether you are proposing what to do with a group of friends one night or proposing to build a student center at your college, you need to have a plan. The level of details and specifics may vary, but no matter what, a good proposal will convince your audience that you can follow through and complete your proposed project—even if it needs a few changes along the way.

Proposals vary greatly in their length, scope, and style. On the one hand, an informal proposal might be a short email or conversation that leads to you acting on a plan. There may be no formal review, but just a quick okay from a friend, supervisor, or client. On the other hand, more formal proposals, such as competitions for research grants or construction projects, may ask for very specific information, such as architectural drawings, a timeline for completion, references, or a detailed budget. Some proposals may be highly competitive, with dozens or even hundreds of submissions for a specific grant or project that may be worth millions of dollars.

While proposals may take different forms and require different components, they all have one goal: getting your audience to say “yes.” Think about a marriage proposal. No one proposes marriage to their partner if they don’t want them to say “yes” (unless maybe you’re in a Jane Austen novel or a Shakespeare play, but save that for your literature class). In order to get your audience to say “yes,” you must consider your audience’s needs, whether they are someone you know well or an organization you need to learn more about.

Many large projects and opportunities issue a call for proposals, the CFP. CFPs vary depending on the industry and discipline. They invite people to send proposals that could meet the needs of their project. CFPs will ask for specific details in the proposed plans that will help the organization make an informed decision about which proposal is the best plan for them, or which proposal has the best potential.

Let’s consider an example. Say your university wants to build a new 300-person dorm on campus. Universities don’t have their own construction companies, so they issue a CFP—often called a request for proposals (RFP) in construction—and ask local companies to submit proposals or bids. The university would have a number of requirements, like the building’s size and location. For their RFP, they would want to see things like architectural plans and costs, but what else might they require? What else might a construction company provide to convince the university that they have the best proposed plan?

The best proposals not only follow the specific instructions of a CFP, but also go above and beyond to help convince their audience to say “yes” and approve their plan. A good proposal lays the groundwork for your project and instills confidence that you are capable of completing it, even as you make adjustments to the project along the way.

As you start to work on your own proposal, this chapter will invite you to think widely about this genre and how it is employed in different disciplines and areas of public and professional life.

II. Rhetorical Considerations: Audience

The proposal requires you to lay out a plan for a larger project. Whether it is a formal proposal for a multi-million-dollar grant or a quick email outlining a project for your boss, you want your proposal to appeal to your audience and convince them to approve your plan. In other words, know your audience.

Knowing your audience can mean a few different things. It can mean knowing the person or organization in charge and what they want to hear—does this person care a lot about specific details, or do they want more of the big picture? Does your audience want a specific and narrow result from your plan, or are they interested in a more ambitious but less predictable outcome? In academic and many professional settings, the requirements for a proposal are laid out in detail in CFPs.

CFPs look a lot like assignment sheets you might have for your class. They identify what an organization is looking for and often include the criteria by which the proposals will be judged. Like a classroom assignment sheet, they can specify length, scope, format, and many other details. Unlike a classroom assignment, though, CFPs may have even more at stake than your GPA. This CFP from the Department of Energy for training in high-energy physics awards grants from $200,000 to $5 million.

In addition, the instructions for grants can require a high degree of special consideration, especially when a lot of money is at stake or a specific goal is identified. For example, these guidelines for proposals from The National Science Foundation are 193 pages long. They include everything from proposal types to formatting guidelines to monitoring and reporting the use of existing grant money.

In fact, some organizations will have full-time employees responsible solely for writing grant proposals. Grant and proposal writers need to possess strong writing skills and a keen awareness of their audience. Many professionals often have to write proposals even if grant writing is not their full-time job. Research scientists write grants in order to obtain funding for their labs, some teachers earn grants for their classes or schools, and many people who work in sales write proposals to potential clients. It’s a good genre to know, regardless of your academic and career path.

The textbook you are reading was made possible by a grant from the University of Illinois at Chicago Libraries for faculty to develop free, open electronic resources for students. For this textbook, the editors had to explain and justify what benefit an open electronic textbook would have for students in the composition classroom. When the textbook project was proposed, the book was not written. Instead, the editors offered an outline of the project, a plan to write it, and a plan to evaluate its implementation. Most projects, from large buildings to book-length studies, go through similar proposal processes.

No matter the context of your proposal, you still need to know what your audience wants in order for them to approve your plan. You have heard teachers and professors say this over and over again, but it’s worth repeating more: read the instructions. Even what seem to be the most arbitrary instructions often serve an important purpose. For very competitive proposals, organizations often ask for specific documents in a specific order and even in a specific format. This helps organizations compare different proposals side-by-side with ease.

The easier you make it for your audience to understand what you are proposing, the more receptive they will be to approving it. Think about doing so in all aspects of your proposal:

- Understand what your audience is looking for in an ideal proposal (you might even be able to track down examples of similar proposals that were successful)

- Include all the requested details and components

- Follow the format and order your audience asks for

- Make sure your writing is clear, direct, and proofread

Another important consideration is explaining why your project matters. Some instructors and teachers will call this answering the “so what?” of a project. According to Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein in their book They Say, I Say (2017), when you answer the “so what?” and explain why your project matters, you engage your audience in a meaningful way that keeps their attention. They write, “[N]ot everyone can claim to have a cure for cancer or a solution to end poverty. But writers who fail to show that others should care or already do care about their claims will ultimately lose their audiences’ interest” (p. 93). Keep in mind that part of your job as a writer is to convince your audience that you have something to say.

Remember that your proposal is a plan, and plans can change. You may encounter unforeseen difficulties, or a seemingly easy task may prove more difficult and time-consuming. Some large projects may need to be scaled back. Some research projects need to adjust their inquiry to something more feasible to meet a deadline or due date. This happens more often than you might expect. The best proposals convince their audiences to approve their plan and assure them that the plan can be adjusted should circumstances change.

More Resources 2.1: Audience

Here’s a little more help for Thinking about Your Audience.

You might also check out this lesson about Understanding the Rhetorical Situation.

III. The Proposal Genre Across the Disciplines

Example 2.1: Academic and Professional Examples

The size of a proposal does not always match its impact. In the height of the 2008 financial crisis, U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson submitted a two-and-a-half-page proposal to the federal government requesting $700 billion. According to Paulson, this amount of money was necessary to stabilize the volatile housing market by purchasing home mortgages and other related financial assets. This proposal would become the basis for the Troubled Asset Relief Program, which attempted to steady the unstable economy during the financial crisis.

Want to see what even more of these competitive grants look like? The U.S. federal government runs a full website to centralize all its available grants. You can find different CFPs on topics ranging from national defense contracts to disease research to international aid programs. In addition, you can see how a typical federal grant functions after the proposal stage. People apply for the grants, and if awarded, they then implement their plan. This process can range from a couple of months to several years. After they have completed their plan, they are required to submit additional reporting to help account for how the money was used and what results came from the grant. For grants that are implemented over several years, the government may require updates throughout the grant period to ensure that projects are following their plans.

IV. Research Strategies: Metacognition

In the proposal stage, you are still developing a topic. You haven’t completed all of your research yet, and part of your proposal will include your plan to research your topic more. At this point in the process, the three most important parts of research are

- knowing what you know,

- knowing what you don’t know, and

- knowing what you need to find out.

All of these are related to thinking or cognition—the things you know and the things you don’t know. Whether you are designing a laboratory experiment or writing a historical analysis, you are engaging not only in thinking, but in thinking about the thoughts you have about your topic. In other words, when writing, you spend a lot of time thinking about how to arrange your thoughts—within a sentence, a paragraph, or an entire paper.

This is metacognition. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, metacognition is the “[a]wareness and understanding of one’s own thought processes.” The more aware we are of those processes—what we know and what we don’t know—the easier it can be to organize our thinking in each step of our research project.

Let’s break down the steps from above. First, you need to know what you know. This means understanding the basics of your topic, usually some of the key foundational ideas or facts. They are often the kinds of things that start to spark your interest in the topic. For example, you might be interested in the rise of social media influencers. You might follow a few and know a little bit about them, but likely not enough to write a research paper.

Next, you need to know what you don’t know. This means identifying the unknowns. these can be basic facts and figures you haven’t discovered yet, possible solutions to the issue you are exploring, or larger concepts that help you interpret data. Following the example above, you might not know the different ways in which social media influencers make money, or what kind of additional work they need to do related to the videos and images they post. Once you have a sense of what you don’t know, you can start to think about the last part: knowing what you need to find out.

Knowing what you need to find out is the basis of a good research plan. Based on your exploration of your topic so far, what do you need to learn more about in order to develop your understanding and eventually develop a thesis? Just like a good laboratory experiment, a proposal should know what it wants to find out without already having the answer. Remember, writing is inquiry—the process of writing a proposal will often help you realize all three of these types of knowledge. Just remember to go back and revise your proposal to make your knowledge as clear to your audience as it has become to you!

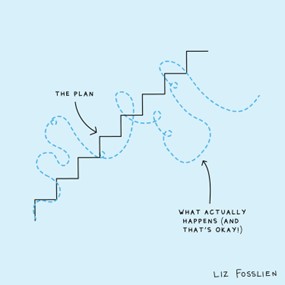

This is called scope. The scope of your project includes its topic and the area of that topic you are looking to explore. Take a look at the image of the funnel. This shows a good way to think about the scope of your topic. You might be interested in climate change, but entire books have been written about that topic. You might need to narrow it down for a research paper, to something like recycling’s effect on climate change. This might be too big of a topic, too, so you might repeat the steps to funnel down your topic to a more manageable scope for your assignment.

In fact, it is often easier to research your topic when the scope of your project is very specific. It allows you to identify research directly related to your ideas.

V. Reading Strategies: Reading with a Purpose

While you draft your proposal, you will want to read selectively in order to get an understanding of your topic and to start planning your project. You might consider some of the following questions as you read:

- What is the purpose of this text?

- Who is the audience?

- What information does it provide?

- With whom is the text in conversation?

- How might you use this text in your project?

- Does the text point to other sources that might prove useful?

To answer questions like these, we don’t always have to read an entire article or chapter. We can read strategically, in this case, reading with a purpose. To read with a purpose means thinking about how you could use that source. As you read, you actively make choices during the reading process to facilitate that purpose without sacrificing understanding. Scholar of reading strategies Tracy Linderholm (2006) claims that this is a necessary transition for college students: “Unfortunately a sizeable number of students do not effectively alter their cognitive processing to meet specific educational goals. For example, many college students are used to reading in order to memorize the material, so they struggle when they are asked to generalize[…]concepts to new situations” (p. 70). Understanding different approaches to reading will help you process information better and put it to use more quickly.

This means that your reading should focus on finding out if a source is useful to you. In this stage of the research process, you will read the abstract first, and maybe the introduction, and then determine whether it is worth reading the rest. Even if you find the article useful, you might flip to a relevant section first, rather than reading the entire thing from beginning to end. This is especially useful for longer sources like books or lengthy reports where you may only need to read the beginning, and then go directly to the relevant section.

As you continue to develop your knowledge of your topic, you will likely find yourself doing this more often. For example, if you are researching issues about free speech in the United States, you might need to read a historical overview of the First Amendment early in your project. You might only need to skim a similar section in an article after you’ve read through several similarly related sources.

Another important part of reading with purpose includes finding sources within a source. An author might cite a study or another article that could be useful to you, even possibly in a way that is different from how the author uses that source. You might see the same source used in multiple articles, and it may be a key part of the conversation around your topic. Look up the citation for the other source and try tracking it down. Sometimes this is as easy as plugging it into Google; other times, you might need to find it through library databases or get some help from a reference librarian.

Library Referral: Staying Organized Means Saving Time

(by Annie R. Armstrong)

Research involves sifting through and managing a lot of information. Ideally, you’ll be gathering more sources than you need, since not all of them will pan out in the end. Things can get out of hand if you don’t have a system for staying organized and efficient. Consider the following strategies for staying on top of your research workflow:

Citation managers such as Zotero and RefWorks help you gather and organize citations for books and articles. They save tons of time by automatically generating bibliographies in any citation style. Ask a librarian about available tools at your school.

Creating a document to track your sources is a more old-school approach, but useful nevertheless. Use the cite button found in library databases and catalogs to copy a citation for each source you’re considering for your research. Copy and paste the permalink for each source as well. A permalink is a permanent, stable link that will help you get back to the source later. You can also take notes on your sources and record where and how you’ve searched for sources on the same document to avoid unnecessarily repeating your steps.

As you read widely and develop your topic, you will want to continue taking notes and keeping track of your sources. Take some time and consider how you manage your notes, sources, and citations. Many researchers use a citation managing app or a note-taking app that stores and saves everything in a central place. These can be easily accessible across multiple devices and can sync to the cloud so you won’t lose all your information if a device is damaged. Other folks may save files to Google Drive or iCloud. No matter what system you adopt, make sure to back up your work.

VI. Writing Strategies: Metadiscourse

We’ve talked about metacognition, or awareness about your thinking. A similar concept called metadiscourse can be applied to writing. Both words have a similar prefix of meta-, which comes from ancient Greek and means something like “beyond,” “above,” or “about.” So, if metacognition could mean something like “thinking about thinking,” metadiscourse means “writing about writing.”

Metadiscourse is writing that tells you about the rest of the piece of writing. Metadiscourse is very effective in proposals. Since you haven’t done the research or completed your project, metadiscourse allows you to talk about what you know so far and what your project will do or will find out.

Example 2.2: Here is an example from a student’s research proposal:

My current research plan centers on investigating restaurant industry policies about tattoos and the experiences of tattooed people in this industry. My initial research has looked into the rules about the display of tattoos and the inconsistent enforcement of them across the restaurant industry. Some of the articles I have read, though, discuss some legal cases about these policies and I need to find out more about the historical impact of such rulings. Ultimately, this project seeks to reconcile society’s changing views about tattoos as a larger part of mainstream culture with the ways the workplace has and hasn’t adapted to them.

This example includes some of the research this student has already done and what he is looking to find out. What do you notice about this language? How does it help you as a reader? While the author might not have a fully formed argument, there is a specific scope and a clear direction. The language of metadiscourse helps bridge what they know with what they are proposing to research further.

Example 2.3: Now take a look at this example of metadiscourse from economist Susan Dynarski’s research paper (2014) about student debt:

In this paper, I provide an economic perspective on policy issues related to student debt in the United States. I lay out the economic rationale for government provision of student loans and summarize time trends in student borrowing. I describe the structure of the US loan market, which is a joint venture of the public and private sectors[…]I close with a discussion of the gaps in the data required to fully analyze and steer student-loan policy.

You often find metadiscourse in the introduction of a longer research paper. Like in the example above, metadiscourse helps to forecast what’s to come. The example above tells you what to expect in the longer paper and how it is organized. It can effectively provide an overview or roadmap of the rest of the paper, direct your reader’s attention, or indicate your stance toward your topic, no matter what genre you are writing. This makes metadiscourse an important tool in all academic writing.

Some students might be hesitant to use metadiscourse. Some feel that they have been told not to use this type of writing in other classes. Some teachers say that students should avoid using the first-person “I” in their writing. Some others suggest that writing should “show and not tell.” In many instances, this is useful advice. If you are writing a summary, you likely don’t want to use the first-person “I” and want to keep it objective. If you’re analyzing a film scene, you want to show your audience significant details, rather than just tell them that the scene is significant without any details.

Check out the following video, which offers additional background on and examples of metadiscourse:

Writing advice is often specific to a genre or situation, instead of being universal. What works in some situations doesn’t work in others. Metadiscourse, when used in the right situations, helps to signal to your reader where a paper or a project is going. It is often used in the beginning of a paper (in the introduction) or the beginning of a project (in the proposal stage). In a proposal, metadiscourse helps connect to your metacognition. It can spell out to your audience what you know and what you intend to find out in your research.

Consider looking back at the examples from different disciplines. Where do you see them employing metadiscourse? How does this language help an audience envision the proposed plan?

Key Takeaways

- Your proposal is a plan. Have a clear direction, even if you need to change some things along the way.

- Keep your audience in mind as you read your assignment sheet or CFP.

- The goal of every proposal is to get your audience to say “yes” to your plan. Always keep that in mind.

References

Dynarksi, Susan. (2014). “An Economist’s Perspective on Student Loans.” ES Working Paper Series, The Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/economist_perspective_student_loans_dynarski.pdf

Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. (2017). They Say, I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing. W. W. Norton and Co..

Fosslien, Liz. (2022). The Plan. https://www.fosslien.com/images

Kessler, Jeffrey. (2015). Funnel for Narrowing Scope. Personal collection.

Kessler, Jeffrey. (2022). Dorm and Classroom Buildings at UIC. Personal collection.

Linderholm, Tracy. (2006). “Reading with Purpose.” Journal of College Reading and Learning, vol. 36, no. 2, 2006, pp. 70–80., https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2006.10850189. p. 70.

“metacognition, n.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2022, www.oed.com/view/Entry/245252. Accessed 27 May 2022.

Nature of Writing. (2018). “Introduction to Metadiscourse.” YouTube. https://youtu.be/4XsNeLF5188.