To say straight off what I’m thinking: now in the Tuileries, the Nymphéas panels are still a mystery to most Parisians. I am not so naïve as to find that surprising: the public will gravitate first to whatever they can easily understand. It has taken quite a while to attract them into our museums to see masterworks; and even now, if you ask a taxi driver to take you to the Louvre, you’ll be driven instead to the department store with that name.[1] We need to remember that the Orangerie museum wasn’t built to impress the masses; but I fail to see why the tastes of discount-store magnates are won by the kind of art featured at our big auction houses, while ordinary French citizens ignore Monet.

In fact, a conspiracy of silence has been at work here, unintentionally bolstered by administrative neglect. On a low wall of the Tuileries terrace, when I visited not long ago, there was one small gray signboard, about as big as my hat-brim, telling visitors that there is something here to see; a few paces farther on there was a gigantic sign advertising a dog show. Passersby had no problem taking the hint. Is this really how we want to acknowledge such a display of art, the likes of which have not been seen in the civilized world for so long a time?

The Beaux-Arts leadership and Monsieur Camille Lefèvre, an excellent architect, have done a masterful job of presenting these panels, befitting the work itself and also the nation that it was meant to honor. What we need to do now is tell our routine-besotted public that they will find here an experience to thrill them. In my own wanderings there I have seen that visitors who come once will come back again without hesitation. Parisians have to know that there is more to be looked at, in the heart of their city, than an answer to a technical problem in painting; for the whole world is here to be seen afresh, scrutinized, apprehended. We need a guidebook for this, a user’s manual, and I am glad to hear that such a document is being created.

But through this doorway we have now passed already, and with our first steps into the gallery the enchantment begins. Where do we go now? How should we pass along these walls, which seem like portals to Neverland?

Well, at the outset, what greets us? An expanse of water, alive with blooms and foliage amid a tempest of fiery sunshine, with the vault of the sky and the mirror of the pond reverberating together, giving rise to those delicate perceptions by which one comes closer, step by step, to knowing the natural world as it truly is. All the radiant energy of sky and earth overwhelm us at once, an intoxication beyond the reach of words, the ecstasy of dream commingled with sensuous encounter, primordial and fresh. A yearning for the Infinite, subtended by an experience of tangible truth, from one reflection to the next and the next on a journey to the last nuance of discrimination.

Such is the essence of these panels, made possible by a twofold miracle, an eye so refined as to see in this way, and the artistic skill to achieve this translation of light, this adventure in color. A valiant brush is so important, aquiver in motion yet steady in purpose, as this artist reveals, working as if guided by some incredible microscope, elemental depths which we would never see without his help. Doesn’t such work come close to representing “Brownian motion”?[2] Well, science is one thing and art another, after all; yet even so, this art brings us face to face with the essential unity of the cosmos, interpreted by our guide and culminating in a rapturous experience of sheer beauty, a supreme awareness achieved in a lifetime of hard observation.

As the Nymphéas sweep us up from watery surfaces into these clouds that seem to wander in infinite space, we leave earth behind and even the sky as well, to revel in harmonies far beyond our own little planet of ordinary emotional experience. Science has not only revealed the eternal motions that subtend the universe; it has taught us to apprehend this knowledge, assimilate it, and act upon it, to live in a new kind of “Nature,” leaving to us the challenge of reifying it in art, provided the tools can be found to evoke and express that awareness. We don’t have to choose between the scientist and the artist; to be completely human we need them both.

Upon the surface of the waters, these lilies, each borne upon a firm palette of leaves, seem to wait in peace for the coming of their own destiny. A fitting subject for deep thought: with no boundaries here, no beginning or end, we encounter this sight in one instant of presentation, on the way to metamorphosis in one panel after another. We need to know at the outset that the sequence of these pictures was stipulated by Monet himself; but what the thinking was that guided him in this arrangement he never told me. So I walk from the main door along the route that any visitor would likely follow, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Monet’s plan was simply to condition our eyes, in this sudden encounter with these tides of light, direct from the sun and also in reflection.

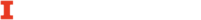

This jardin d’eau which we come upon first is seen quite clearly in the panel that Monet has set up as the start of the series. We can think of it as a tableau témoin, a strictly conventional exposition of a subject, with no special effort required from ordinary visitors accustomed to art museums. No sky, no clouds, no complications—lots of tranquil sunlight with not much reflected from anything we see, heavy limpid water illuminated in a classic sort of way—it’s late afternoon, around five o’clock, and benign Providence has laid out these flower-beds very nicely, with lots of big greenery providing contrast with these lovely blooms like little flames of rose and white. Monet knew how to present the tranquility of such ordinary light, enfolding these flowers like a rich offering to heaven from the earth. What we see here couldn’t be any easier to understand. The poetry is so simple and clear, though also so lofty, than anyone with an ordinary education can be readily enthralled by it.

I have called this a tableau témoin: a conventional experience of gallery-style light, our baseline for visual experience in museums, as this is the kind of interpretation we have grown up with. Yet here the sky is overcast. Two big masses of darkness—one of them a mix of night with day—roll into the scene, perhaps to collide in a few minutes and unleash a rainstorm. But for this moment the sun still dominates, enlivening the waters, throwing thick slivers of cloud through a portal of blue sky; hints of an unseen and distant combat, while as if in response to danger, a stricken water lily trembles, as a portent of some catastrophe to come.

But these turn out to be only the usual conflict of light with dark, the inevitable contrasts of a day in a garden. If there are hints here of an impending storm, the panels that follow take us into a magnificent pageant of light, a celebration of solar fire. Like dazzling symphonic variations, four additional panels explore this theme. In peaceful sunshine, the water lilies are arrayed beneath a companion willow through whose fronds bolts of sun-fire are allowed to pass, arrows of light whose vitality seems to spread over sky and water alike, reflected again and again and again, an indescribable ecstasy for the human observer. The lilies themselves, encompassed by a cloudscape mirrored on the pond surface, seem carried into the air by the power of the water; they shimmer as if in a surf, where fluid, commingled energies of earth and sky respond to the will of these great blossoms, heady with sensual life.

So it is that art reveals to us the joyful energy in an expanse of water, the vault of the sky, the clouds, the flowers, all with so much to say to us, yet powerless to do so without Monet. Ethereal moments in a timeless drama, the natural world in performance for itself, with mankind as participant and observer.

Now and then I have gone to sit for a while on the bench where Monet observed so much in his jardin d’eau. With my untrained eyes, I had to work hard to follow, from that distance, Monet’s artistic journey to the limits of his own insights. The antithesis of that monkey in Florian’s fable,[3] Monet pours torrents of light into his own “magic lantern”—too much, one might say, if it were possible to complain about this abundance of luminous energy, like a Milky Way in layer upon layer, beguiling us with visions of the Infinite.

For its own place in all this—whatever that place might be—the water-lily only bears witness to the motions of the universe, these spectacles of sheer color that carry us away in our own thoughts and imaginings. Also, to finish the story: here in sanctuaries of foliage we encounter spent passions in pools of still water, presented to emphasize this water-garden as a place of contrasts, as storms of light from the blinding sky seem to set this world ablaze, and as the sky itself draws light from the glowing earth.

Whether it be for life or death, in a contest between flower and sun, eternal fire will always overwhelm the tender foliage. Protected by the willows, these sprays of water-lilies can savor a moment of triumphant bloom; but the clouds, like an exquisite coverlet burned through by the brilliance of the sky, overspread the flowers in the mirror of the pond, sweeping them away like rare prizes into the heights of the blazing sky, while touches of darker greenery, perceived through melodies of mist, mauve, blue, and rose, tell of the combat between ephemeral life and incandescent space. And all across this field the struggle is life itself, a primordial struggle for each successive instant of being, translated here into a contest of luminescence. The drama of Nymphéas thus becomes a universal truth, apprehended by human beings whose own lifelong struggles with mastery and submission are the plot at the core of this unending story. In these oceans of space and time, where torrents of light overwhelm our capacity to see, rainbows collide and converge, shatter into softness like fireworks, melt, disperse, and take shape again, all heightening the intensity which we feel within. Words fail in the presence; it takes an artist’s magic to open our bewildered eyes to the shock of the universe, the inexpressible enigma of the world. Even those with no awareness will take a step here towards comprehension. Over time, it will happen.

Something more: an entirely new experience in seeing. This triumph of sunlight throws us into a quandary of response, this iridescent transparency, this soft light with no definite hue, where sky and earth gently embrace amid scattering flowers and joyous clouds. A fragile, irresistible masterpiece, a moment of complete ecstasy transcending all harsh experience, the sublime omega-point in the artistic quest to which Monet abandoned himself happily, the sensual peace in the final stroke of the brush. And because we have learned recently that there truly is a “music of the spheres,” we have clearance to dream of new concerts, of hearing and of seeing alike, conjoined in a universal music.[4]

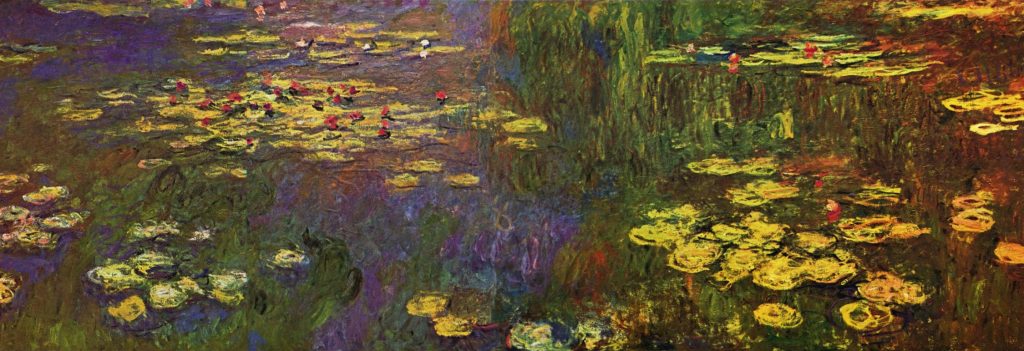

Yet as we return to the panels, we find here a somber blue evening, where ghostly greenery stands in now for all the triumphant, climactic flourishing we saw earlier. And finally, as we come to the close of the series, a culminating sight: through a forest of reeds, fading water lilies, spectral in a brilliant sunset, embody a provisional end to one more cycle in a vast and interlinked array.

So it is that Monet, at the height of his powers, brings us into a world seen afresh, an experience that fosters a natural maturing of our own capacity to see, so that we too can partake of this broader awareness. This succession of images teaches us to see the world as through a glass brightly, in diffusions of transmogrified light, in reflection upon reflection: deeper harmonies encountered in adventures of disorientation. An incomparable light-show contest between sky and earth, culminating in exultation, a communion with the world that also fulfills and completes our own capacity to feel.

I wish I could still hear that friendly voice, gentle and magisterial, as we stood together amid the natural wonders of his jardin d’eau. “While you chase after the world in itself, as philosophically as you can” he said with his genial smile, “I put my own work into seeing every sight possible in connection with hidden realities. When we reach the level of deep relationships among the things that we see, we cannot be far from truth, or at least not far from what we can know of it. I have looked only at what the world can reveal to us, trying to bear witness through my painting. Does that count for nothing? Your problem is that you try to reduce the world down to your own scale; but by broadening your awareness of nature you will learn more about yourself. Let’s join hands, and help each other see things better.”

- As one of the massive “arcades” structures erected in the Haussmann era, Les Grands Magasins du Louvre opened in the Rue de Rivoli in 1855 and remained in business until 1974. ↵

- Though the discovery of Brownian motion dates from 1827, it came into mainstream news in the early 20th century, thanks to work by Einstein and the French physicist Jean Perrin. In 1926, shortly before the Nymphéas were installed in the Orangerie, Perrin had received a Nobel Prize for his work with this phenomenon. ↵

- An author of fables in the tradition of Aesop and La Fontaine, Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian was active in the later decades of the 18th century. Of noble lineage, he died in prison during the Revolution. ↵

- [Clemenceau’s note] Monsieur George Grappe has written that “Claude Monet treats waves of light as musicians treat waves of sound. These two sorts of vibration correspond: their harmonies answer to the same ineluctable laws, and in painting hues are juxtaposed according to rules as firm as those governing two notes in musical harmony. Even more: in a single series, different episodes link together like different movements in a symphony. Pictorial drama unfolds according to the same principles as musical drama.” ↵