Bruce Michelson

From the past four hundred years of cultural history in the West, what texts do we have in which the leader of a powerful nation, someone famous and consequential in statecraft or war or other front-page action—President, Prime Minister, monarch, anyone who might qualify for Hegel’s welthistorische roster—writes thoughtfully and at length about the arts? Plausible candidates can be tallied on one hand. From the legendary salons of Frederick the Great, no substantial documents of the sort survive; though Napoleons I and III raided their treasuries to bankroll painting and sculpture, decking out palaces, theaters, and galleries for national and personal glory, what they actually said about the fine arts was scattered and commonplace. From the past few decades, a case might be made for Václav Havel, the polymath who eventually became President of the Czech Republic, a reluctant leader for a small nation. Beyond these, however, we have to scrounge. With so much discourse coming at us from seats of power since the dawn of printing, this paucity is not only stunning but also grimly eloquent for what it signifies: a chronic disconnect between our political elites and the creative spirit of the nations they oversee.

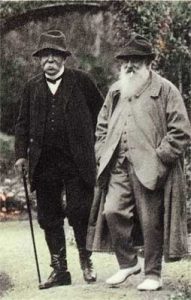

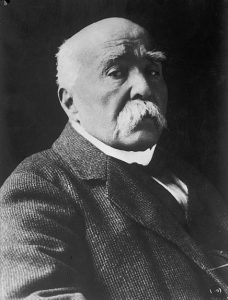

One rare exception is this short book that Georges Clemenceau wrote in the final year of his life, a career of extraordinary action and consequence for France and also for modern Europe. In the middle of May 1928, bothered by bad weather at his seaside cottage in the Vendée, he had come back to his Paris apartment on Rue Benjamin Franklin, across the Seine from Trocadéro; and Jean Martet, his personal secretary and confidant, paid him a visit there in the ground-floor study. Eighty-six years old now, “The Tiger of France,” as he was still being called in the newspapers, was feeling his age, plagued by a stubborn cough and fiery pain in both of his hands. Nonetheless, holding court behind his massive Louis XV desk, he was, as usual, brimming with intentions and resolve. “At present I am writing a kind of monograph on Monet,” he announced. “Yes indeed; does that surprise you? Well, I have felt for a long time it was my duty to write it. And so I am now at it.”[1] He was struggling, he admitted, to fold so many years of his personal experience with Monet into a meditation about his achievement. But two weeks later, Clemenceau sounded playful and buoyant about how things were going; and when he saw in Martet some reservations about precious days and energies getting lost in a book about painting, the old homme d’état offered a tide of confident rationale. “I’m writing this book precisely because it’s different from Au Soir de la Pensée [the two-volume memoir he had finished over the winter]…. With Monet I’m doing something else—something which follows naturally, nevertheless…. I’m taking up a question of which I’ve never spoken but of which I ought to speak—the world’s emotional impulse as expressed in religion or art. Well, I shall take art.” With these lines, as round and sonorous in Clemenceau’s French as they seem in Milton Waldman’s translation, he was only warming up, testing and enjoying prose that would find its way into the new monograph; and keeping quiet, Martet just took it all in. Clemenceau’s Monet book would be about a courageous man’s life-culminating struggle to do the impossible with paint and canvas, to finish one huge and supreme masterpiece before he died: “What I want to tell is the story of that conflict—a conflict which ended in both victory and defeat, a victory because he left behind a vast body of work, including many splendid things, a defeat because in that domain there is no such thing as success. And between us, I shan’t mind giving a lesson to the art critics, whose number is ludicrous.”[2]

Through sixty years of turbulent center-ring public life, Clemenceau was not one to be daunted by anything; and if the spirit moved him now to write about his three decades of intimate friendship with the greatest Impressionist and one of the most famous artists of his time, no phalanx of professional critics would scare him off the track. Jailed at the age of twenty-one as a troublesome hothead by Louis Napoleon, Clemenceau had been Mayor of Montmartre at thirty, struggling to save Parisian lives during the long siege and the bloodbath of the Commune. Thereafter, in the Chamber of Deputies and later in the Senate, as the nation recovered and the belle époque began, he had made himself a standard-bearer for the anti-colonialist radical Left, his polemics bringing him fame as le tombeur des ministères—“the toppler of governments”—and in all seasons, in public office or out, he busied himself with founding, editing, or writing regularly for one combative journal after another. In the dangerous struggle to exonerate Alfred Dreyfus at the end of the century, he and his ally Émile Zola had stood fast at the center of an enormous furor; and throughout those many years in politics and public life there had been scandals and duels, volumes of prose, even a novel and a play. Having skirmished his way up to being a cabinet Minister of this and that, and then Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909, he had served again in that post, and as Minister of War at the same time, during the final year of the bloodiest crisis in European history.

Even with all this—and with his “private” life so packed with affairs and dalliances that his biographers have despaired about chasing them all down—Clemenceau’s involvements with the arts in his own time, and also with the mission and operations of France’s great museums, surpass those of any other leader of a Western republic; and books have been written about the scope and impact of his engagement.[3] There is space here for a few examples. As early as the 1880s, he helped lead the campaign to erect Jean Gautherin’s imposing statue of Diderot, the free-thinking Enlightenment hero, at Place St. Germain des Prés on the Left Bank, to gaze with a bemused defiance at the grand and ancient church across the way. A few years after, when Monet and his fellow Impressionists organized to save Édouard Manet’s Olympia from foreign purchase and conserve it in the national collections, Clemenceau’s advocacy and clout did much to get that accomplished; in the fall of 1906, the opening days of his first term as Prime Minister, he personally ordered this painting’s transfer out of its exile at the Musée de Luxembourg and into the galleries of the Louvre. In the autumn of 1891 he led a similar effort to acquire Whistler’s ever-controversial Arrangement in Gray and Black (“Whistler’s Mother”) with public funds and accord it a similar place of honor; in Rodin’s long wrangle with the Societé des Gens des Lettres over the planned monument to Balzac, Clemenceau intervened repeatedly and combatively on the sculptor’s behalf. In his own journal La Justice, with his friend Gustave Geffroy (one of those genuine art critics, who would later write an important book about Monet, and also a book about Clemenceau himself) he called—successfully—for an experiment with musées du soir, galleries kept open late with free admission, so that the working multitudes of Paris, who commonly had to be at their jobs six days every week, could actually come out and see exhibitions. His personal collection of antique kōgō, exquisitely-carved or sculpted incense boxes from Japan, grew to more than three thousand items; recently they have been the focus for special showings and studies. Along with Monet and Geffroy, Clemenceau was also friends with Manet, with Raffaëlli (who painted him giving a speech in a packed hall near Montmartre), and with Degas, the Goncourt brothers, Cézanne, Octave Mirbeau, Renoir, Zola, Sarah Bernhardt, Daudet, Morisot, Huysmans, Mallarmé—the list of his companions and connections in the arts reads like a checklist of the avant garde from his prime. In 21st century America our A-list politicians keep clear of such company. A public liking for the contemporary arts, for any cultural action that might strike some klatch of potential voters as daring or esoteric, is the kind of behavior that makes a handler cringe.

As he began writing about Monet in the spring of 1928, Clemenceau was setting out on a final voyage into the heart of his own enthusiasm for painting. Monet, whose work he loved so much, was also one of his favorite human beings, though in temperament the two men often seemed a mismatch. Monet could be reclusive, passive, given to extended bouts of self-pity and despair; Clemenceau was notoriously inexhaustible in his energy, convictions, and perseverance. During the Great War, and especially in the early Twenties, Monet’s fugues of reluctance about finishing the Nymphéas panels, these culminating Grandes Decorations that he had promised the nation, drove his old friend to levels of rage and exasperation that nearly brought their friendship to an end. Nonetheless, the long history they had shared, a mutual admiration reaching back to 1886, did much to pull them both through these troubles. It was Geffroy who had introduced them in that year; and though they had met at least once long before, this was the encounter that took hold, growing in strength in the nineties when Monet joined Clemenceau’s side in the battle to bring Alfred Dreyfus back from Devil’s Island and disgrace. After many visits up to Giverny, where Monet was creating his gardens at his final home, Clemenceau chose the nearby village of Bernouville for his own weekend retreat in 1902, buying an old half-timbered house there in 1908 and keeping it until 1922. The surviving correspondence makes clear that in various ways these men completed one another. This was especially true for Clemenceau, for whom these journeys into aesthetic life, this immersion in nuances of the natural world and the mysterious quiet music of garden sunlight, provided solace from the whirl and brawl of his political doings in Paris, and also from the horrors of the Front, the trenches he visited so often during the protracted slaughter less than fifty miles away.

At Giverny, Monet had begun experimenting with paintings of his water-lily pond around 1899,[4] offering a show of about forty canvases at the gallery of Durand-Ruel (his longtime agent in the city) about ten years later. The subject had evolved into a deep commitment, perhaps beyond the point of obsession. By some accounts the artist worked on more than 150 studies of the lilies, the waters, and the play of light between 1904 and 1908; many of these he subsequently destroyed in outbreaks of frustration.[5] As the catastrophe of the Great War broke upon Europe and soon came unnervingly close—on the plains around Giverny one could hear the mauled boom of heavy artillery along the Marne—the two friends began to dream of a capstone œuvre of Impressionist insight, grand in physical dimensions as well as in ambition: a set of enormous panels for the people of France, to celebrate victory if it ever came, or at least to mark an end to the carnage. For such a project Monet’s studio wasn’t nearly big enough; and after Clemenceau won a place on the Senate’s Army Commission, as well as on its Commission on Foreign Affairs in January 1915, plans went forward for an enormous free-standing building east of the family’s rambling pink house. With more than three thousand square feet of floor space, with big skylights fifty feet above, elaborate sun-screens, and central heating, it now serves as the gift-shop for the Foundation that conserves the home and the gardens. Work began in July of that year, and Monet had moved his easels and panels into it by December.[6] On such a large private building, how could construction proceed so quickly when the national effort to supply the poilus and the trench system was urgent and the needed materials were in high demand? By some accounts Clemenceau himself was responsible[7]—and if so, no surprise: ferociously dedicated to winning, The Tiger regarded the old painter and this promised, ultimate work as national treasures in the struggle for survival. France must come through this ordeal as France, with its culture alive and robust; and with his characteristic conviction, Clemenceau had decided that Monet and these unfinished Nymphéas were to be ranked among the assets that mattered most.

In November of 1917, when he became Prime Minister for the second time as well as Minister of War, Clemenceau was seventy-six years old, and the story of his all-out commitment to victory—the numerous treks, with no fanfare and small escort, into the mud with the troops; the wrangling with Foch, Pétain, Haig, and the other clay-footed generals; the long skein of rousing speeches in arenas of power and to the public in the streets; the personal intervention in countless aspects and levels of the effort to triumph—this part of the Clemenceau story has filled many volumes. In those years and afterward, he was also fighting on a second front, coming to Giverny when he could slip away from Paris or the command center at Bombon, or writing to Monet privately and directly, or to the painter’s step-daughter and guardian Blanche Hoschedé-Monet, all in a quest to keep the artist glued together psychologically, and also physically, and committed to their pact. Fat now and a heavy smoker, often awash with wine and losing his eyesight to cataracts, Monet was susceptible to losing heart, fearing that he could no longer muster the drive and the psychological wherewithal to finish these panels well, yet also complaining at times about the planning by others as to where and how the paintings would be displayed, if he ever did get them done. About those matters Clemenceau applied constant pressure in Paris as well as up at Giverny; and as usual he made things happen. In September of 1920, with Geffroy’s support, he secured a firm commitment from Monet to complete at least a dozen of the Nymphéas panels and donate them as a set to the Republic.[8] About two years after, in response to Clemenceau’s urging and also his interactions on the painter’s behalf with leading ophthalmologists, Monet began a three-step sequence of cataract surgery that improved his vision somewhat, as well as his morale[9]—at least for the time being. Meanwhile there were surprises, disappointments, and showdowns about the site for the art: when Clemenceau’s party was voted out of office in 1920, hopes for a new pavilion on the grounds of the Hôtel Biron faded for lack of clout and funding; an architect had to be found to refit the Orangerie as a recourse[10]—and when that work was completed, Monet slid into an emotional tailspin that nearly brought the whole plan and the friendship to a close. In February of 1926, however, Monet assured Clemenceau that twenty-two Nymphéas panels were finally finished, and that they would be ready for shipment to Paris as soon as the paint was dry.[11] Over the course of the summer and fall, lung cancer and other ailments closed in. On December 5, Monet died at Giverny with Clemenceau at his bedside. There are photographs of him in the front rank of the small group of mourners at the churchyard down the road on the day of the burial; and in photos from a day in the following spring, May 17, 1927, The Tiger is out front once again, aged, solemn, serene, proud, at the inaugural ceremonies for the Nymphéas galleries, the Tuileries home where we find them now.

About the translation

Claude Monet was Clemenceau’s second book for the Plon press in a series called Nobles Vies—Grandes Œuvres. In his earlier work, a short appreciation of the Athenian orator Demosthenes, Clemenceau observes that the craft of holding an audience proves to be “… less a matter of fine and careful arguing—an indulgence for commentators and critics—than of giving a sense of one’s whole self as committed to the fight.”[12] That comment says as much about Clemenceau’s own way with language as it might about Demosthenes: throughout his half-century as a writer and orator, Clemenceau crafted his own sentences to resonate in the ear as well as in the mind. Another of his friends from the arts, Stéphane Mallarmé, was famous for describing poetry as a kind of incantation. We can find that value in play throughout French verse and prose of the fin de siècle, and Clemenceau often exemplified it at the rostrum and on the printed page. This strategy wasn’t empty theatrics; from all accounts he was to the core a man of passions, of high enthusiasm in whatever cause or avocation he took up, whatever line of inquiry or reasoning he plunged into. As a statesman, insurgent, adventurer, connoisseur, amorist, novelist, playwright, he put everything on the line—and not surprisingly, his discourse at times can be opulent and orotund beyond the bounds of modern taste. In Claude Monet he has much to tell us, and he does the telling with astounding zeal.

For an English translation, therefore, a basic challenge is to convey that substance and intensity with no sacrifice in clarity, no loss of meaning or tone in sorting out what can seem at times like a wilderness of embellishment and syntax. The only other English version we have, completed more than eighty years ago, keeps faith with the original in a word-by-word sort of way; consequently, it can lose modern readers in fogbanks with regard to Clemenceau’s intention, voice, and nuanced observation. To hear this formidable man breathing as he comments, reminisces, extrapolates, and grieves; to conserve the vividness and drive in the stories he tells of personal experience with his friend; and most important, to open up this rarest of texts in which a great divide between our cultural and political life is challenged, I’ve worked to make this possible. For the sake of clarity, long ceremonious sentences in the original French are sometimes reworked into two or more shorter ones; when superlatives and other modifiers accumulate in ways that hinder a reader’s journey through insights and appreciations that matter, they have here and there been condensed. Veteran translators have reviewed my work to help me ensure that it sustains a proper faithfulness to the original text; I am especially grateful to Jane Kuntz and Douglas Kibbee at the University of Illinois, Anne D. Hedeman at the University of Kansas, and Pierre Michel at the Université de Liège, whose expertise in the ways of the French language runs very deep, for advising me on many spots where the job needed to be done better.

Included here, to enrich a sense of Clemenceau as a longtime, passionate advocate for the arts, are paragraphs that he excised from “La Revolution des Cathédrales” (published in La Justice on May 20, 1895) when he revised that essay to be the seventh chapter of Claude Monet thirty years later. Not translated into English before, these passages make an open challenge to Félix Faure, who had recently become President of France, to step forward on the Republic’s behalf and purchase as many of the Rouen Cathedral series as could possibly be acquired, so that their sequence, and the shifts and progressions they catch in the play of sunlight on the façade, could be comprehended and enjoyed by the French public. These paragraphs appear in note 6 for the translated text. In the Appendix, also to boost our enjoyment of Clemenceau as knowledgeably embroiled in these matters, there are three lively opinion-pieces from the nineties, each of them also from La Justice, about curating and purchasing at the Louvre, and the conservation and accessibility of France’s great collections. “Le Louvre Libre” appeared on March 18, 1894; “Au Louvre” on June 6 of the same year; and “Musées du Soir” on November 21. Clemenceau gathered these essays into his volume Le Grand Pan (1896); they appear here in English for the first time.

Bruce Michelson

Urbana, Illinois

October 2015.

- Jean Martet, Georges Clemenceau. Trans. Milton Waldman (New York: Longman’s, 1930), 121. ↵

- Martet, Georges Clemenceau, 206. ↵

- A recent wide-ranging collection on this subject: Michel Brousset, Béatrice Bougerie, and Mélanie le Gros, eds., Clemenceau et les Artistes Modernes: Manet, Monet, Rodin… (Paris: SOMOGY Éditions d’Art, 2013). ↵

- Karin Sagner-Düchting, Monet at Giverny (New York: Pegasus, 1999), 50. ↵

- In a letter to Paul Durand-Ruel on April 23, 1907, Monet says of the experiment so far: “At the very most I have five or six that are possible; moreover I’ve just destroyed thirty at least and this is entirely to my satisfaction.” See Richard Kendall, ed., Monet by Himself: Paintings, Drawings, Pastels, Letters (London: Little, Brown, 2000), 198. ↵

- Paul Hayes Tucker, “Revolution in the Garden: Monet in the Twentieth Century,” in Tucker et al., Monet in the Twentieth Century (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1998), 66–67. ↵

- See for example Carla Rachman, Monet A&I (Art and Ideas) (New York: Phaidon, 1997), 300. ↵

- Tucker et al., 75. ↵

- From the winter and spring of 1923, Clemenceau’s letters to Monet about the surgery, letters of medical substance as well as encouragement, are collected in Georges Clemenceau: Correspondance 1858–1929, ed. Sylvie Brodziak and Jean-Noël Jeanneny (Paris, BNF, 2008), 641–665. ↵

- Pierre Gorgel, Claude Monet: Waterlilies (Vanves-Cedex: Hazan, 1999), 21. ↵

- Tucker et al., 83. ↵

- Clemenceau, Démosthène (Paris: Librarie Plon, 1926), 50. My translation. ↵