Chapter 1: Beginning “Where Illinois Began”

This chapter of A Bicentennial Crossroads and the ten that follow it describe the companion exhibitions and public programs produced by our state’s Crossroads: Change in Rural America host organizations. Those exhibitions and programs collectively formed a remarkable survey of continuity and change over two hundred years of rural Illinois’s existence, illuminating themes that connect its evolution with that of rural America in general.

Eagerly anticipating Halloween, more than 150 residents of southwestern Illinois crowded into every nook and cranny of Chester Public Library on October 16, 2018, to hear tales of the sinister and the supernatural drawn from their own local lore, accompanied by vivid descriptions of the historical contexts from which those stories emerged. One of the narratives with which local historian Shane Wagner regaled his standing-room-only audience recounts the Curse of Kaskaskia.[1]

Established by Kaskaskia Indians and French Jesuits in 1703 on a narrow peninsula between the Okaw and Mississippi rivers near the confluence of those two waterways, the village of Kaskaskia grew to become the largest and arguably the most important French colonial settlement in central North America, supplying New Orleans with flour ground from the wheat grown on the surrounding fertile farmland.

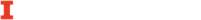

In the early nineteenth century, having been transferred from French to British to American control, Kaskaskia served as the seat of government of the Illinois Territory and subsequently the first capital of the state of Illinois. [2]

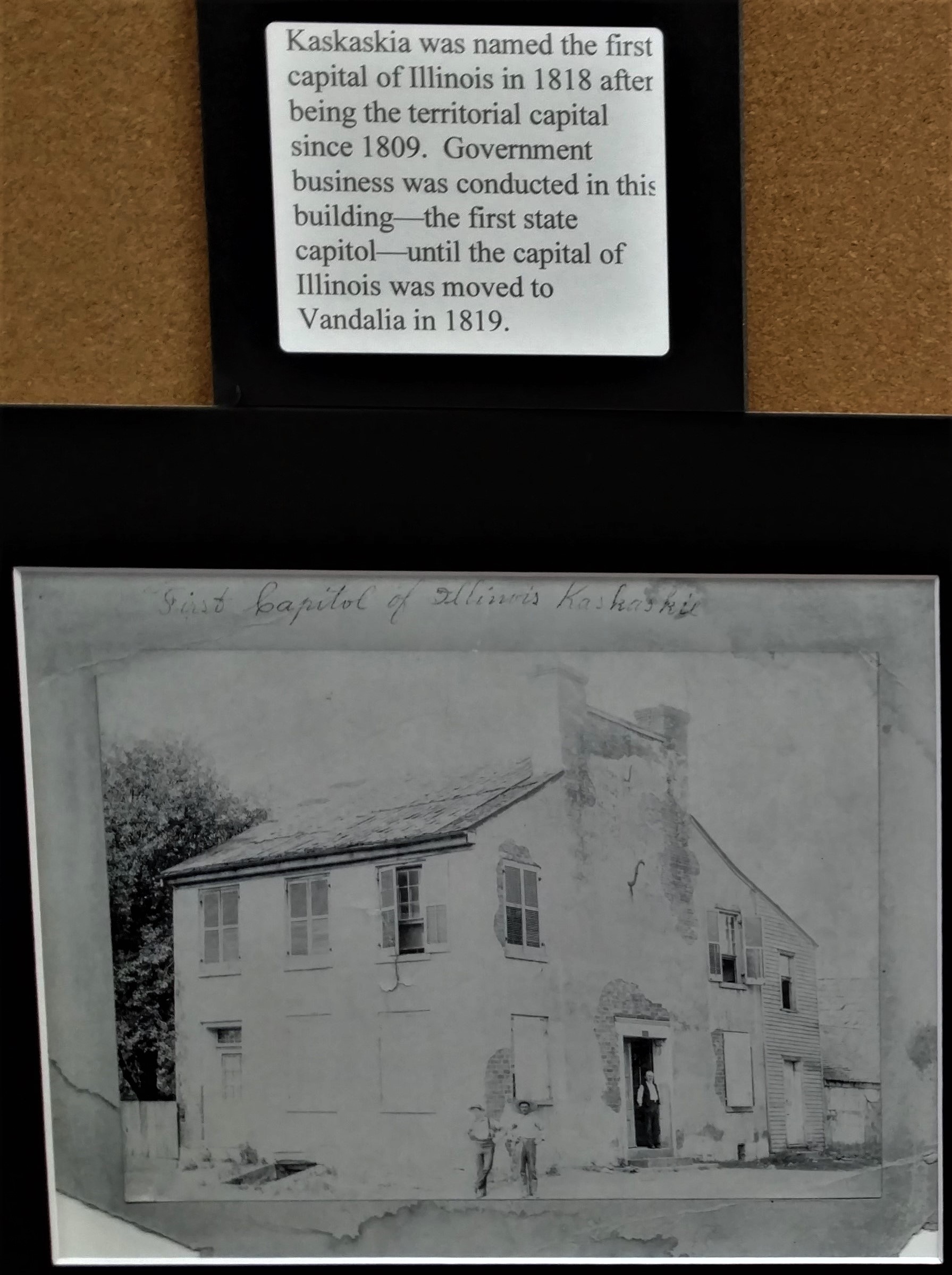

Eventually, however, one of the factors that enabled Kaskaskia to prosper—its proximity to a major river—proved to be its downfall. Flooding, exacerbated by deforestation-induced erosion, increasingly plagued the town. In 1881, the Mississippi, anticipating T.S. Eliot’s subsequent description of it as “a strong brown god–sullen, untamed and intractable,”[3] pummeled through the narrow isthmus at the north end of the peninsula and flowed into the channel previously occupied by the last few miles of the Okaw. The town, now greatly diminished in population and prominence, found itself marooned on an island between the old and new courses of the Father of Waters.[4]

Today, the once bustling village that housed Illinois’s original capitol encompasses fewer than twenty residents. Although the community officially remains within Illinois, it is accessible only by way of Missouri, via a bridge across the old channel of the Mississippi, which forms the island’s western boundary.[5]

To some southwestern Illinoisans, the fact that Kaskaskia, despite its essential role within the state’s history, is now literally so marginalized from Illinois that one must leave the state to go there symbolizes the degree to which such distant cities as Springfield and Chicago have eclipsed their region within the statewide milieu.[6]

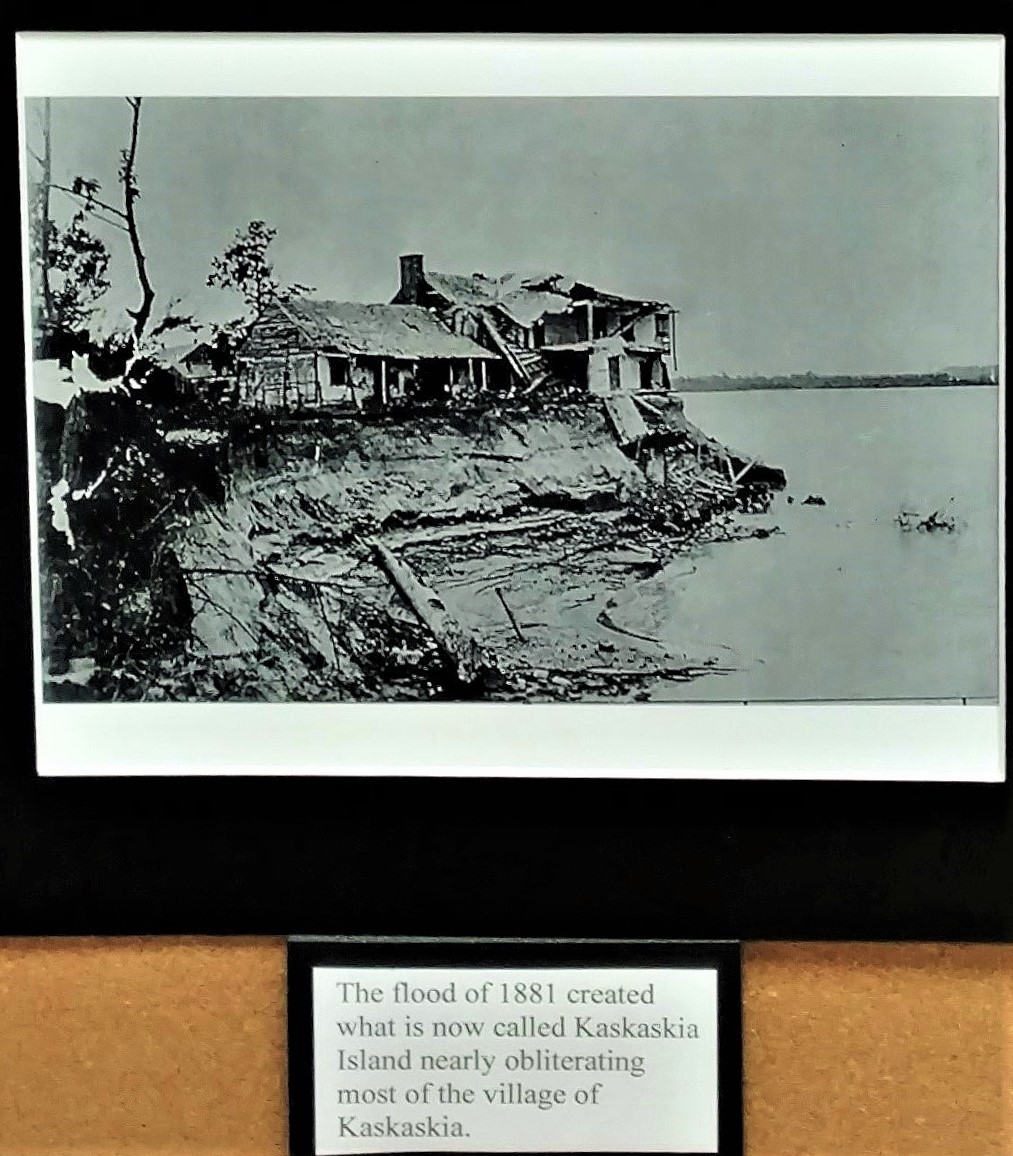

Might Kaskaskia’s reversal of fortune be attributable to a curse? According to Shane Wagner, stories that claim so, incorporating elements from both oral tradition and written sources, have been circulating locally since the 1890s. In one version, a priest exasperated by the residents’ rejection of his attempts to elevate their moral standards, which had deteriorated as the founding Jesuits’ influence waned, invoked divine wrath upon Kaskaskia as he departed it (either voluntarily or by force, depending on the telling). In another rendition, the fateful spell was cast by a Native American man who, despite his reputation as a pious and upstanding member of the community, was forbidden from marrying the young French woman with whom he was in love; her disapproving father tied him to a log and set him afloat in the Mississippi to drown.[7]

Chester Public Library presented Wagner’s program, “History & Mystery: Randolph County Folklore”[8] in conjunction with its hosting of Crossroads: Change in Rural America, a Museum on Main Street exhibition produced by the Smithsonian Institution. The Illinois tour of Crossroads: Change in Rural America coincided with the state’s Bicentennial, facilitating reflection upon the significance of rural life throughout Illinois’s history, as well as Illinois’s contributions to the history of rural America. Illinois Humanities, which administers the Museum on Main Street program in Illinois in cooperation with the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, selected Chester as the first site on the exhibition’s statewide tour for multiple reasons. In addition to the merit of the library’s application, those reasons included the community’s proximity to Kaskaskia, cursed though it supposedly may have been. That proximity offered an opportunity to accentuate the relevance of the subject matter of Crossroads within the state’s two-hundred-year history.

Yet another factor that made Chester especially suitable as the starting point for the exhibition’s journey through Illinois—one of the first three states to host Crossroads, in addition to South Carolina and Florida—is that Debra Reid, co-curator of the exhibition along with Ann McCleary, was raised on a nearby farm and graduated from Chester High School. An accomplished museum practitioner and historian of the rural Midwest and South, Reid is curator of agriculture and the environment at The Henry Ford in Michigan and professor emerita at Eastern Illinois University.[9] Her visit to Chester Public Library during the opening of Crossroads on September 12, 2018, had the character of a homecoming and drew an audience comparable in size to the one for Wagner’s program the following month. Her presentation illuminated connections between her local roots and her scholarly career and between her life experience and the content of the exhibition.[10]

“We were in the unique position here to have one of the curators of the exhibit come back home and speak on an exhibit that she helped create for the Smithsonian. How can you open an exhibit any better than that? We were thrilled,” said administrative librarian Tammy Grah.[11]

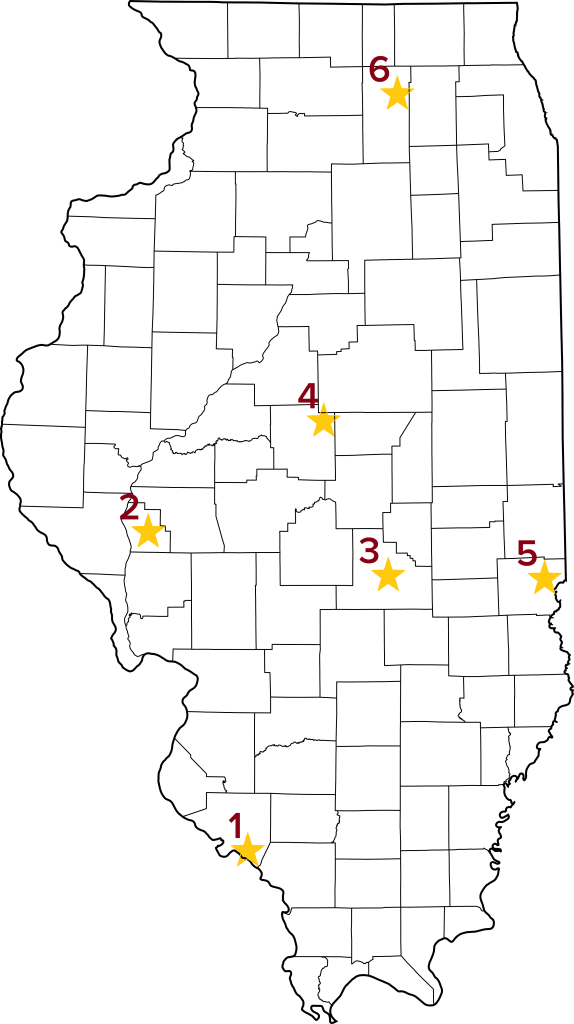

Crossroads: Change in Rural America remained in Chester for six weeks, then proceeded to five other small-town cultural institutions in Illinois: the Old School Museum in Winchester, the Lake Shelbyville Visitors Center, the Atlanta Museum, Marshall Public Library, and the DeKalb County History Center in Sycamore, where the tour concluded in June 2019.

1. Chester Public Library, Chester (Randolph County)—September 8-October 20, 2018

2. Old School Museum, Winchester (Scott County)—October 27-December 8, 2018

3. Lake Shelbyville Visitors Center, Shelbyville (Shelby County)—December 15, 2018-January 26, 2019

4. Atlanta Museum, Atlanta (Logan County)—February 2-March 16, 2019

5. Marshall Public Library, Marshall (Clark County)—March 23-May 4, 2019

6. DeKalb County History Center, Sycamore (DeKalb County)—May 11-June 22, 2019.

The locally focused companion exhibitions and public programs that the six host organizations produced to supplement Crossroads compellingly addressed many of the most significant themes in the life of rural Illinois, past and present. Collectively, they formed a remarkable survey of continuity and change over two hundred years of rural Illinois’s existence. Additionally, the ways in which the host organizations conducted their work reflected and responded to ongoing change in rural Illinois, contributing to their communities’ and regions’ efforts to sustain and enhance their cultural vitality.

- Gwendy Garner, “Overflow Crowd Enjoys Library’s ‘Haunted’ Talk,” Randolph County Herald-Tribune, October 23, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20181024183429/https://www.randolphcountyheraldtribune.com/news/20181023/overflow-crowd-enjoys-librarys-haunted-talk; Tammy Grah, Brenda Owen, and Carolyn Schwent, telephone interview with author, October 22, 2019. ↵

- Companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, Chester Public Library, Chester, IL, September 8-October 20, 2018; David MacDonald and Raine Waters, Kaskaskia: The Lost Capital of Illinois (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2019), 1-71. ↵

- T.S. Eliot, “The Dry Salvages” (London: Faber and Faber, 1941), 1-2. ↵

- Companion exhibition, Chester Public Library, 2018; MacDonald and Waters, Kaskaskia: The Lost Capital of Illinois, 72-114. ↵

- Patrick M. O’Connell, “Illinois’ First Capital is an Island That’s Home to Just 18 People. Recent Flooding Has Made it Even More Isolated,” Chicago Tribune, July 3, 2019, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/environment/ct-kaskaskia-illinois-first-capital-floodwaters-20190703-kxw42avvzvgrlpooev2ccrw73a-kxw42avvzvgrlpooev2ccrw73a-story.html. ↵

- The author bases this observation on numerous informal conversations that he has heard in southwestern Illinois, where he has lived for much of his life. ↵

- Shane Wagner, Ghosts by the Riverside: The Haunted History of Chester and Old Kaskaskia (Chester, IL: Chester Public Library, 2019), 27-33; MacDonald and Waters, Kaskaskia: The Lost Capital of Illinois, 155-166. ↵

- A subsequent version of Wagner’s presentation, delivered online on October 29, 2020, is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W80KqnqnIh8. ↵

- “Dr. Debra A. Reid, Professor Emerita,” Department of History (website), Eastern Illinois University, https://www.eiu.edu/history/faculty.php?id=debra_reid&subcat=. ↵

- Gwendy Garner, “Smithsonian Exhibit Opening Draws Crowds,” Randolph County Herald-Tribune (Chester, IL), September 19, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20180919200555/https://www.randolphcountyheraldtribune.com/news/20180919/smithsonian-exhibit-opening-draws-crowds. ↵

- Tammy Grah, Brenda Owen, and Carolyn Schwent, telephone interview with author, October 22, 2019. ↵