Chapter 6: Generating Energy (and Occasionally Controversy)

Alongside agriculture, the generation of energy from natural resources has influenced the ongoing evolution of rural Illinois in multiple ways, as the companion exhibitions and programs presented by the Crossroads: Change in Rural America host organizations emphasized. In some instances, resource extraction and energy generation have intersected with economic, social, and cultural tensions, eliciting controversy and conflict.

“If it can’t be grown, it must be mined,” declares a bumper sticker that has been known to appear on vehicles in rural Illinois. Some of the companion exhibitions and programs presented by Crossroads: Change in Rural America host organizations discussed mining or the generation of energy from fuels obtained by that method.

Several coal mines were closed and mine shafts filled in order to construct Shelbyville Dam and form Lake Shelbyville. The impact of coal mining upon not only the economy but also the social fabric of Shelby and surrounding counties during much of the twentieth century is evidenced by Sundown Town, a 2018 novel by Kevin Corley and Douglas E. King, the subject of a well-attended program presented in conjunction with the opening of Crossroads at the Lake Shelbyville Visitors Center.[1] (Sundown Town will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.)

Around the same time that the Army Corps of Engineers dammed the Kaskaskia River near Shelbyville, the Corps also straightened the section of the river from Fayetteville to its confluence with the Mississippi, cutting off twenty-six meanders and reducing its length from fifty-two to thirty-six miles to make it more navigable by barge. Additionally, the Corps constructed a lock and dam less than a mile from the river’s mouth to assist barges in making the transition from the Kaskaskia to the Mississippi.[2]

One of the main reasons why the Kaskaskia River Navigation Project was initiated was that 1.8 billion tons of coal lay within fifteen miles of the river, according to a 1967 estimate,[3] and much of that coal was mined and transported by Peabody Coal Company. For those reasons, the channelized section of the Kaskaskia was colloquially (and derisively) called “Peabody’s Ditch.”[4]

Despite declines in the coal industry, the navigation channel still regularly accommodates barges hauling materials to and from agribusiness and manufacturing facilities along that section of the river.[5] (Although the Kaskaskia River Navigation Project was not among the topics directly addressed by the Crossroads host organizations’ companion exhibitions, its creation, maintenance, management, and use—and controversies surrounding all of the above[6]—fascinatingly illustrate significant changes that have occurred in rural Illinois in the past half century.)

Shelby Electric Cooperative, which began providing electricity to its member-owners in 1939,[7] is still going strong even though there are no longer any coal mines in operation in Shelby County.[8] The cooperative obtains some of its electricity from solar and wind power, but much of it comes from the Prairie State Energy Campus.[9]

Founded by Peabody Energy (which later sold its stake in the facility) and co-owned by multiple public utilities, the Prairie State Energy Campus has been in operation since 2012.[10] It consists of a power plant fueled by coal extracted from an adjacent underground mine located near the juncture of Washington, St. Clair, and Randolph counties (well within fifteen miles of the channelized section of the Kaskaskia River).

The facility incorporates extensive clean-coal technology in an effort to minimize pollution and environmental degradation while maximizing cost efficiency.[11] The extent to which it actually achieves those goals has been a topic of debate and controversy within and beyond the region.[12] Illinois’s “Climate and Equitable Jobs Act,” signed into law by Governor J.B. Pritzker on September 15, 2021, stipulates that the Prairie State Energy Campus must reduce its carbon emissions by at least 45 percent by 2035 and eliminate carbon emissions altogether by 2045 if it is to continue operating.[13]

The Shelbyville-based cooperative contributed a substantial section of the Visitors Center’s companion exhibition. Using photographs and other artifacts from the cooperative’s early years, the segment illustrated the transformative effects of the availability of electricity upon agriculture and farm life. It included promotional cartoons indicating what one kilowatt hour of electricity could do for farmers and farm families: grind a hundred pounds of grain, milk a cow for twenty days, hoist two tons of hay, cut a third of a cord of wood, provide lighting for a whole evening’s reading, power a sewing machine for two months with average use, or wash a large load of laundry.[14]

Shelby Electric Cooperative is affiliated with Prairie Power, Inc., a consortium that also includes the Winchester-based Illinois Rural Electric Cooperative, the subject of a major section of the Old School Museum’s companion exhibition.[15]

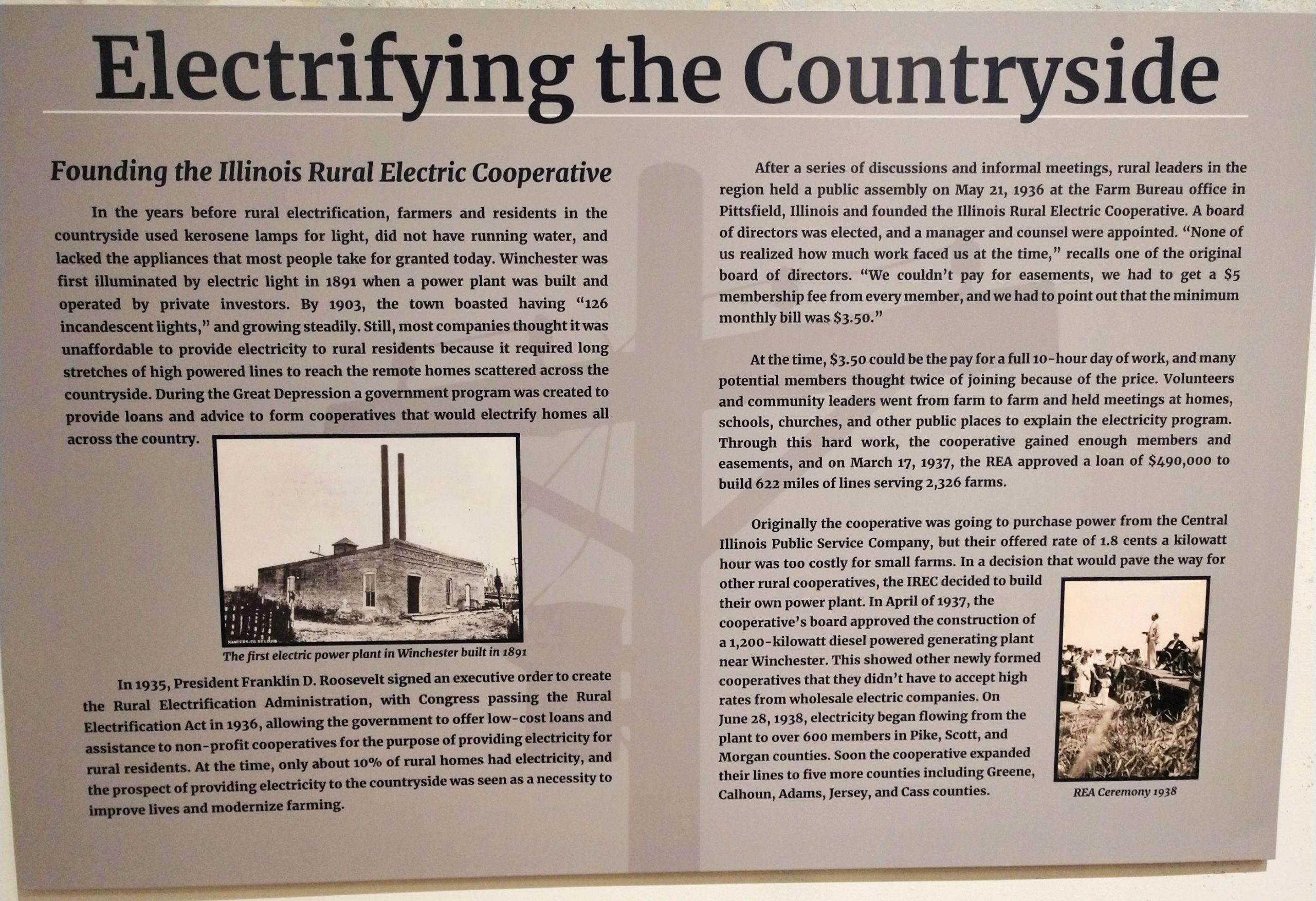

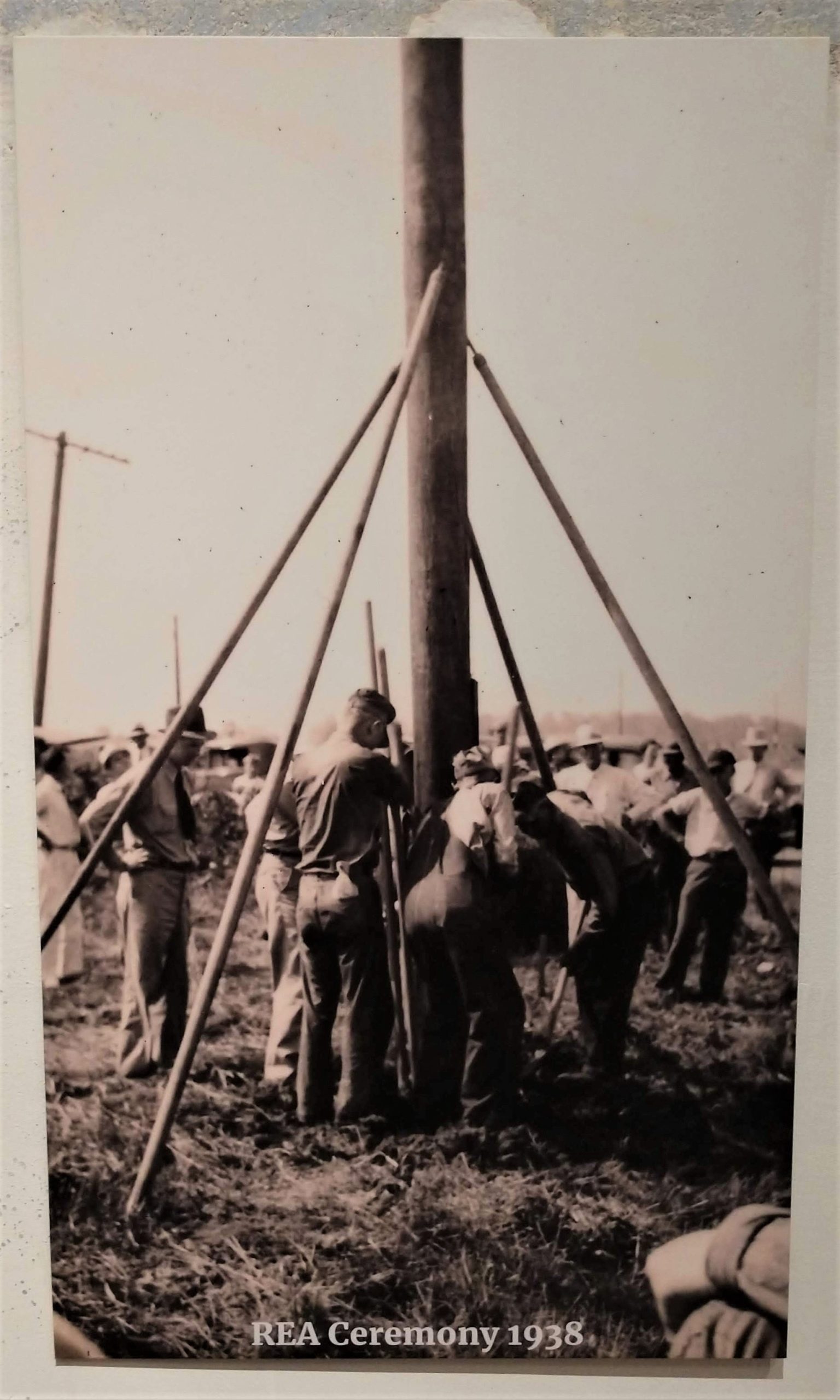

The Illinois Rural Electric Cooperative (IREC), which serves members in Scott, Morgan, Pike, and portions of adjacent counties, has embraced innovation throughout its history. Local leaders founded the cooperative in 1936, shortly after the passage of the Rural Electrification Act, which made federal low-interest loans available for the establishment of nonprofit entities to provide electricity to rural Americans. Over the next year, the founders tenaciously visited farms, churches, and schools throughout the area, eventually recruiting enough dues-paying members and obtaining the easements necessary to qualify for a Rural Electrification Administration loan of $490,000.

They concluded that building their own power plant would be more cost-effective in the long term than purchasing electricity from an existing one, making IREC one of the first such entities to construct generating facilities of their own. Interestingly, the plant was fueled with diesel rather than coal. Electricity began flowing in June 1938, reaching more than six hundred member-customers.[16]

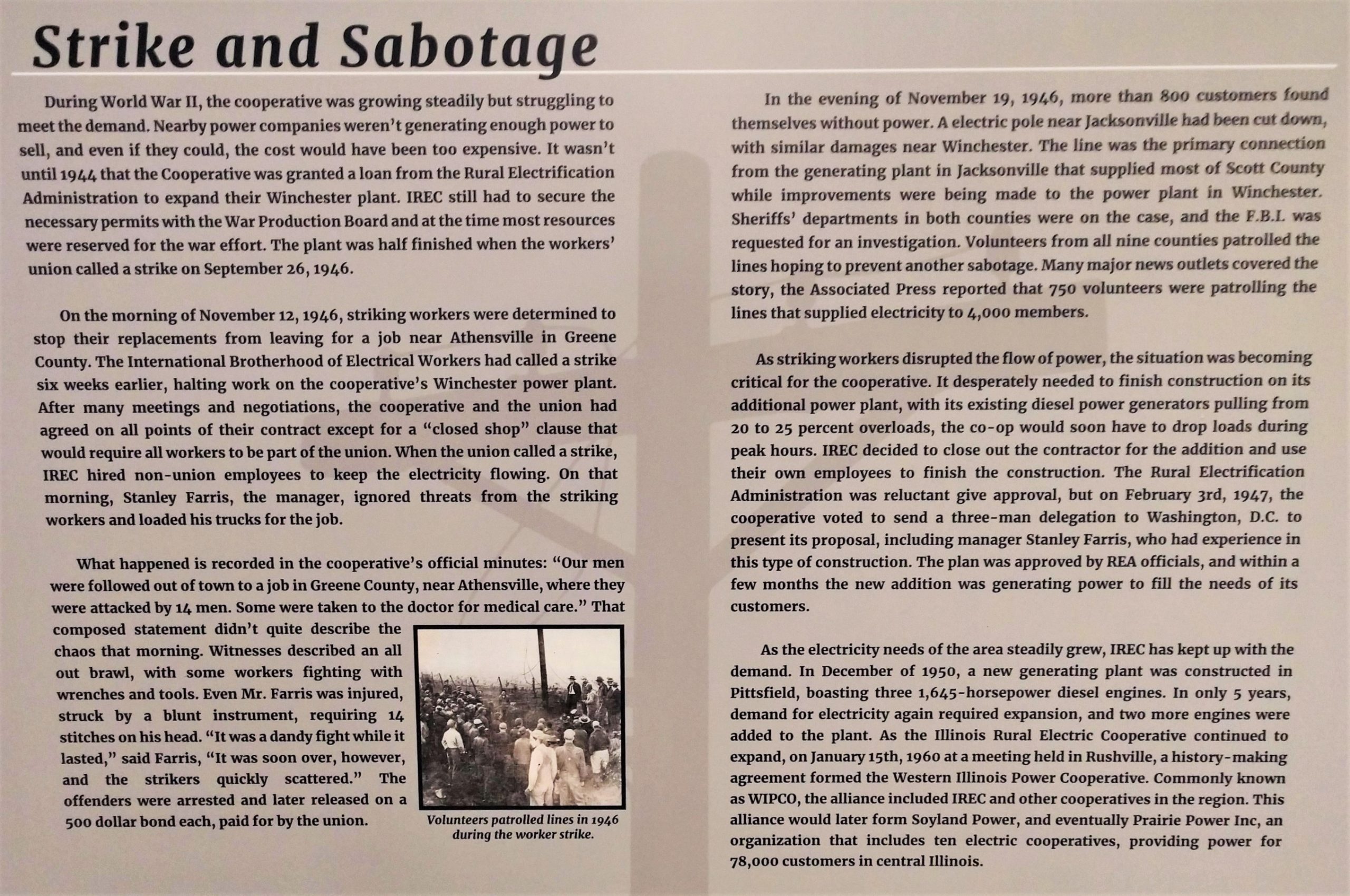

The Illinois Rural Electric Cooperative made national headlines in the fall of 1946, when an International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers strike coincided with the cooperative’s expansion of its Winchester power plant in response to rapidly increasing demand. “After many meetings and negotiations, the cooperative and the union had agreed on all points of their contract except for a ‘closed shop’ clause that would require all workers to be part of the union. When the union called a strike, IREC hired non-union employees to keep the electricity flowing,” said the Old School Museum’s exhibition text, written by local historian Wilson Newman.

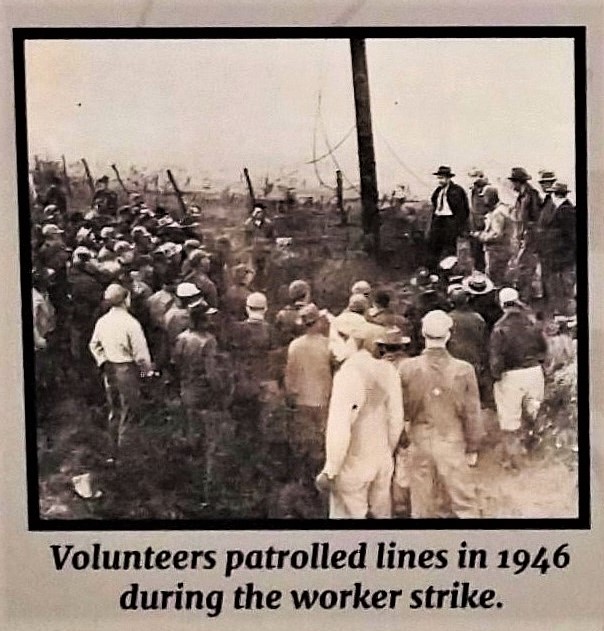

On November 12, 1946, fourteen of the striking workers followed their replacements to a job site near Athensville in Greene County and physically attacked them. “Witnesses described an all-out brawl, with some workers fighting with wrenches and tools,” according to the exhibition text. “The offenders were arrested and later released on a five-hundred-dollar bond each, paid for by the union.”

“In the evening of November 19, 1946, more than eight hundred customers found themselves without power. An electric pole near Jacksonville had been cut down, with similar damages near Winchester. The line was the primary connection from the generating plant in Jacksonville that supplied most of Scott County while improvements were being made to the power plant in Winchester. Sheriffs’ departments in both counties were on the case, and the FBI was requested for an investigation. Volunteers from all nine counties patrolled the lines, hoping to prevent another sabotage. Many major news outlets covered the story. The Associated Press reported that 750 volunteers were patrolling the lines that supplied electricity to four hundred members,” the exhibition explained.

“As striking workers disrupted the flow of power, the situation was becoming critical for the cooperative. It desperately needed to finish construction on its additional power plant. With its existing diesel power generators pulling 20- to 25-percent overloads, the co-op would soon have to drop loads during peak hours. IREC decided to close out the contractor for the addition and use its own employees to finish the construction.” Although the Rural Electrification Administration was reluctant to approve the plan, a delegation from the cooperative traveled to Washington and persuaded the administration to do so. “Within a few months, the new addition was generating power to fill the needs of its customers.”

“In 2006, the cooperative began offering wireless broadband internet,” Newman wrote. “Today, the cooperative operates over forty wireless broadband towers across five counties. In 2016, IREC began installing fiber-optic cable to provide high-speed internet to its cooperative members, providing internet that compares to many major cities’.”[17]

Old School Museum President Tricia Demby Wallace, who has family roots in Winchester and spends considerable time there but makes her primary residence in the Northeast, commented, “I don’t have fiber optic where I live in New Jersey, and we have it in Winchester—in the county in Illinois where there is no stoplight!”[18]

Furthermore, “in 2005, the IREC completed a 1.65-megawatt wind turbine in Pike County, becoming the first co-op in Illinois to complete such a project and winning a US Department of Energy ‘Wind Cooperative of the Year’ award,” Newman’s text explained. The cooperative’s solar power plant, constructed near Winchester in 2014, “features 2,223 solar panels and is able to generate about five hundred kilowatts, reducing $75,000 in electricity costs every year. Along with Prairie Power’s renewable energy plants, IREC is able to provide fourteen percent of its peak demand with renewables.”[19]

A segment of the DeKalb County History Center’s companion exhibition (also available as an online exhibit) that was devoted to renewable energy development within the county had immediate relevance. The county government had enacted a moratorium on construction of solar and wind farms in March 2017 pending passage of ordinances regulating them, which occurred the following year.[20] In the interim, issues related to sustainable-energy generation became the topic of several well-attended public meetings, extensive local media coverage, and considerable debate among DeKalb countians.[21]

“The county’s solar ordinance was passed in March 2018, and the first solar power special-use permit request was for a DeKalb farm,” the exhibition text noted. “As of November 2018, there were forty-plus projects going through the special-permit process ahead of the Illinois project lottery.”[22]

The exhibition continued, “The creation of a wind ordinance was a little more complicated. Driving through central DeKalb County, some people might believe that wind turbines symbolize progress while others might argue they represent the destruction of life in the county. When working on the new county ordinance, the main concerns were residential setbacks, noise, and shadow flicker. Concerned Citizens of DeKalb were very vocal about stopping the wind-farm initiative and posted signs throughout the county. After numerous opportunities for residents to meet and discuss their concerns, a new ordinance was passed on November 21, 2018. Community members were generally in favor of the new requirements, but a potential developer called them unworkable and canceled their project.”[23] Artifacts featured in the exhibition included a solar panel and a “No Wind Farms” sign.

Regarding the controversy over solar- and wind-power development in DeKalb County, History Center Director Michelle Donahoe said, “We addressed it head-on, and there was no pushback, and I think some people were kind of impressed, like, ‘Wow—this isn’t just stuff from a hundred years ago. It’s decisions today that are really going to be shaping the future.’”

That experience convinced the center’s staff and volunteers that they “can push the envelope a little and make it a safe place to have the discussion, and that was really the goal—we’re not presenting pro or con; we’re just saying that this was a big part of our local history for the last year, and this is the story,” Donahoe commented.[24]

- Brenda Elder and Freddie Fry, telephone interview with author, October 1, 2019; Companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, Lake Shelbyville Visitors Center, Shelbyville, IL, December 15, 2018-January 26, 2019. ↵

- “Kaskaskia River Project and Jerry F. Costello Lock and Dam Master Plan,” US Army Corps of Engineers St. Louis District, 2017, https://www.mvs.usace.army.mil/Portals/54/docs/recreation/rend/Kasky%20Master%20Plan%202018%20DRAFT_16OCT2018.pdf?ver=2018-10-16-162924-713, 1-15. ↵

- “History of Jerry F. Costello Lock and Dam,” U.S. Army Corps of Engineers St. Louis District (website), accessed April 1, 2023, https://www.mvs.usace.army.mil/Missions/Recreation/Kaskaskia-River-Project/History/. ↵

- “Kaskaskia Canal–Boom or Bust?,” Decatur Herald (Decatur, IL), August 30, 1978, 39; “No Transformation in Kaskaskia Area,” Southeast Missourian (Cape Girardeau, MO), August 25, 1978, 5; “Times Changed for Public Works and So Did View of Kaskaskia” (editorial), The Southern Illinoisan (Carbondale, IL), August 23, 1978, 4. Note: These are three of several articles and editorials published by newspapers in Illinois and Missouri in August 1978 that draw upon the reporting of Timothy Middleton of the Metro-East Journal in East St. Louis (which no longer exists). ↵

- “Ports and Facilities,” Kaskaskia River Port District (website), accessed April 1, 2023, https://www.kaskaskiaport.com/Facilities.html. ↵

- Throughout its history (which now spans half a century), the Kaskaskia River Navigation Project has had fervent supporters and equally vehement detractors. Their assessments of the project’s impacts upon the environment, the economy, and the quality of life in the region have varied widely, as multiple newspaper articles and editorials, many of which are available on Newspapers.com, attest. ↵

- “About Shelby Electric Cooperative,” Shelby Electric Cooperative (website), accessed April 1, 2023, https://shelbyelectric.coop/shelby-electric-cooperative. ↵

- “Number of Mines for All Coal, Total, Illinois, All Mine Statuses,” U.S. Energy Information Administration (website), https://www.eia.gov/coal/data/browser/#/topic/38?agg=0,2,1&rank=g&mntp=g&geo=0000g&freq=A&datecode=2019&rtype=s&maptype=0&rse=0&pin=<ype=pin&ctype=map&end=2019&start=2001; “Shelby County Coal Data,” Illinois State Geological Survey (website), accessed April 1, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20230425174855/http://isgs.illinois.edu:80/research/coal/maps/county/shelby. ↵

- “Power Supply Portfolio,” Prairie Power, Inc. (website), accessed April 1, 2023, https://www.ppi.coop/about/assets/. ↵

- Michael Hawthorne, “Clean Coal Dream a Costly Nightmare,” Chicago Tribune, July 12, 2010, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-met-coal-plant-20100710-story.html; “Ownership,” Prairie State Energy Campus (website), date accessed or published https://prairiestateenergycampus.com/about/ownership/; “Peabody Energy Sells Interest in Prairie State for $57 million,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 21, 2016, https://www.stltoday.com/business/local/peabody-energy-sells-interest-in-prairie-state-for-57-million/article_16abb4cc-3c18-5b12-989c-a3523c2d92f8.html; Jeffrey Tomich, “Prairie State Fuels Debate,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 5, 2010, https://www.stltoday.com/news/prairie-state-fuels-debate/article_a39b6af9-9446-5750-89c9-4ffce24a00de.html. ↵

- “Environment,” Prairie State Energy Campus (website), accessed April 1, 2023, https://prairiestateenergycampus.com/environment/; “Technology,” Prairie State Energy Campus (website), accessed April 1, 2023, https://prairiestateenergycampus.com/technology/. ↵

- Allysia Finley, “Illinois Democrats Play Politics With the State’s Electricity,” Wall Street Journal, July 16, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/illinois-democrats-unemployment-prairie-state-climate-energy-change-fuel-prices-11626451190; Michael Hawthorne, “Coal-Fired Power Plant in Southern Illinois a Major Obstacle to Biden’s Push for Carbon-Free Electricity by 2035,” Chicago Tribune, January 21, 2021, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/environment/ct-biden-climate-illinois-coal-20210121-27fuo4lzovdejp2lf3ptpt2vqe-story.html; Michael Hawthorne, “Towns Pay a High Price for Power,” Chicago Tribune, September 4, 2013, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-met-costly-coal-plant-20130904-story.html; Kelsey Landis, “Why All Eyes on Marissa Coal Plant? Its Closure Could Leave Customers Billions in Debt,” Belleville News- Democrat, June 3, 2021, https://www.bnd.com/article251844248.html; Jeffrey Tomich, “Prairie State fuels debate,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 5, 2010, https://www.stltoday.com/news/prairie-state-fuels-debate/article_a39b6af9-9446-5750-89c9-4ffce24a00de.html. ↵

- Eric Schmid, “Illinois’ New Energy Plan Promises Massive Shift Away From Fossil Fuels,” St. Louis Public Radio, September 16, 2021, https://news.stlpublicradio.org/government-politics-issues/2021-09-16/illinois-new-energy-plan-promises-massive-shift-away-from-fossil-fuels. ↵

- Shelby Electric Cooperative, section of companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, Lake Shelbyville Visitors Center. ↵

- “Service Territory,” Prairie Power, Inc. (website), accessed April 1, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20201028212804/https://ppi.coop/about/territory/. ↵

- Companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, Old School Museum, Winchester, IL, October 27-December 8, 2018. ↵

- Companion exhibition, Old School Museum. ↵

- Tricia Wallace, telephone interview with author, October 15, 2019. ↵

- Companion exhibition, Old School Museum. ↵

- “The Land,” section of a companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, DeKalb County History Center, May 11-June 22, 2019, content from which is available at https://dchcexhibits.org/crossroads/land/. ↵

- Katie Finlon, “County Plan Committee Hears Residents’ Concerns About Health, Safety of Wind Farms,” Daily Chronicle (DeKalb, IL), May 24, 2018, https://www.shawlocal.com/2018/05/23/county-plan-committee-hears-residents-concerns-about-health-safety-of-wind-farms/ai0izw/; Katie Finlon, “Dozens Air Concerns About Proposed Wind Farms Before County Planning Committee,” Daily Chronicle (DeKalb, IL), April 26, 2018, https://www.shawlocal.com/2018/04/25/dozens-air-concerns-about-proposed-wind-farms-before-county-planning-committee/a5k4l3l/; Keith Hernandez, “Residents Meet to Discuss Plans, Concerns Swirling Around Wind Farms,” Daily Chronicle (DeKalb, IL), March 25, 2018, https://www.shawlocal.com/2018/03/25/residents-meet-to-discuss-plans-concerns-swirling-around-wind-farms/ardh3an/; Stephanie Markham, “DeKalb County Board Approves Moratorium on Wind, Solar Farms,” Daily Chronicle (DeKalb, IL), March 15, 2017, https://www.shawlocal.com/2017/03/15/dekalb-county-board-approves-moratorium-on-wind-solar-farms/alth8w2/; Stephanie Markham, “DeKalb County Board OKs Wind Testing Towers,” Daily Chronicle (DeKalb, IL), June 22, 2017, https://www.shawlocal.com/2017/06/22/dekalb-county-board-oks-wind-testing-towers/aulttp9/; Kevin Solari, “Alternative Energy Talks Continue at County Board Meeting,” Daily Chronicle (DeKalb, IL), July 23, 2018, https://www.shawlocal.com/2018/01/23/alternative-energy-talks-continue-at-county-board-meeting/ayw8ww4/; Kevin Solari, “Discussion on Wind, Solar Farm Moratorium on Docket for Thursday Meeting,” Daily Chronicle (DeKalb, IL), September 28, 2017, https://www.shawlocal.com/2017/09/27/discussion-on-wind-solar-farm-moratorium-on-docket-for-thursday-meeting/aqn6fkl/; Drew Zimmerman, “DeKalb County Committee Recommends 2nd Public Hearing for Wind Testing Towers,” Daily Chronicle (DeKalb, IL), February 22, 2017, https://www.shawlocal.com/2017/02/22/dekalb-county-committee-recommends-2nd-public-hearing-for-wind-testing-towers/awkiq1q/; Drew Zimmerman, “DeKalb County Board to Vote on Solar Ordinance,” Daily Chronicle (DeKalb, IL), March 20, 2018, https://www.shawlocal.com/2018/03/19/dekalb-county-board-to-vote-on-solar-ordinance/ajz6cw6/. ↵

- “The Land,” section of a companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, DeKalb County History Center, May 11-June 22, 2019, content from which is available at https://dchcexhibits.org/crossroads/land/. ↵

- “The Land,” section of a companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, DeKalb County History Center. ↵

- Michelle Donahoe, telephone interview with author, September 27, 2019. ↵