Chapter 4: Fertile Ground for Agricultural Change, Part 2

One participant in the Illinois tour of Crossroads: Change in Rural America compellingly demonstrated how changes in the lives and livelihoods of local farming families have exemplified and perhaps contributed to regional, statewide, and national trends in agriculture and rural life.

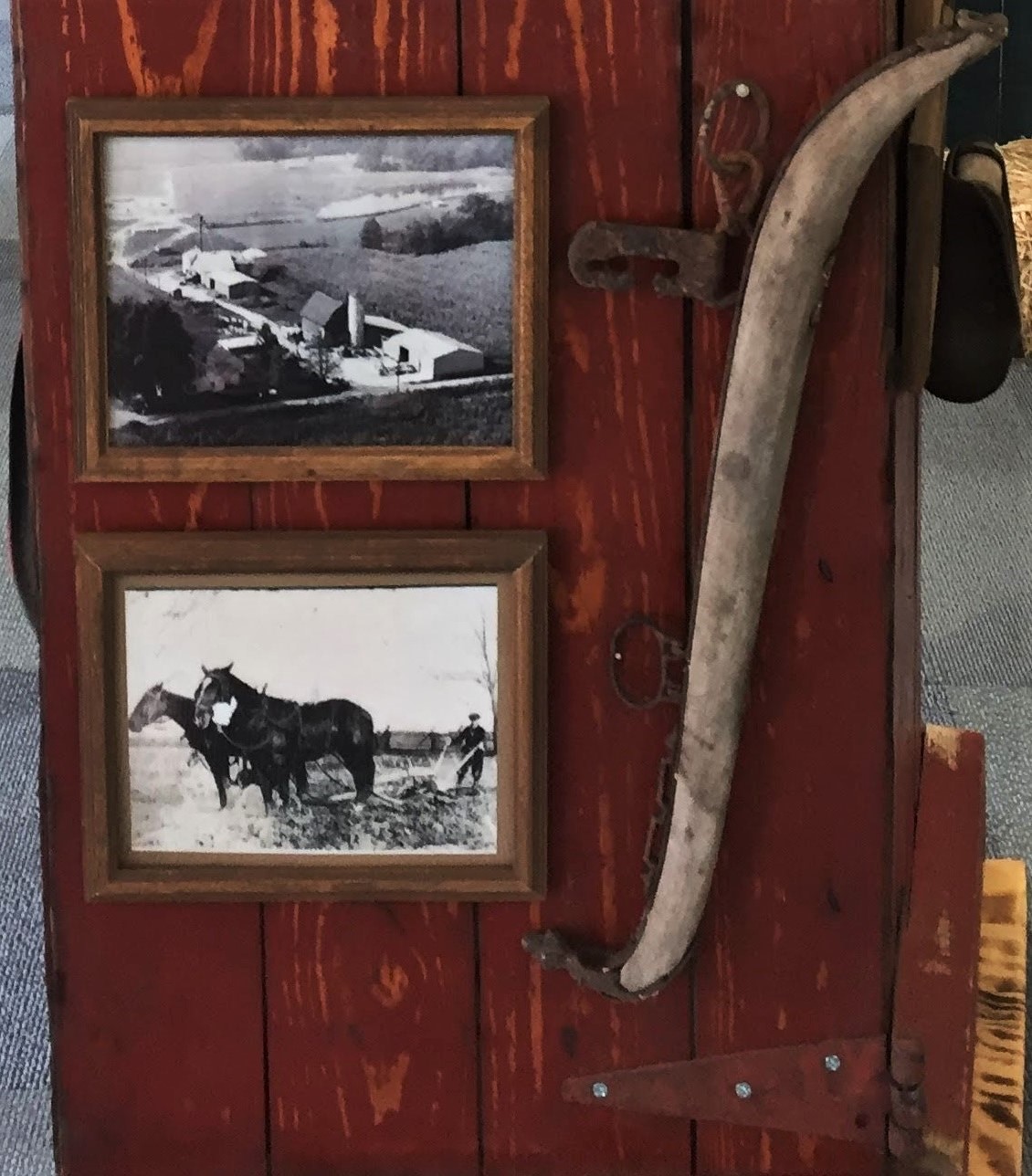

Like the DeKalb County History Center, Marshall Public Library in east-central Illinois, which hosted Crossroads: Change in Rural America from late March through early May 2019, prominently featured centennial farms in its programming, as well as its companion exhibition. One of the two main sections of the library’s locally focused exhibition examined the histories of two long-established farms—those belonging to the Guinnip family and the Miller family—as microcosms of the evolution of agriculture in Clark County.

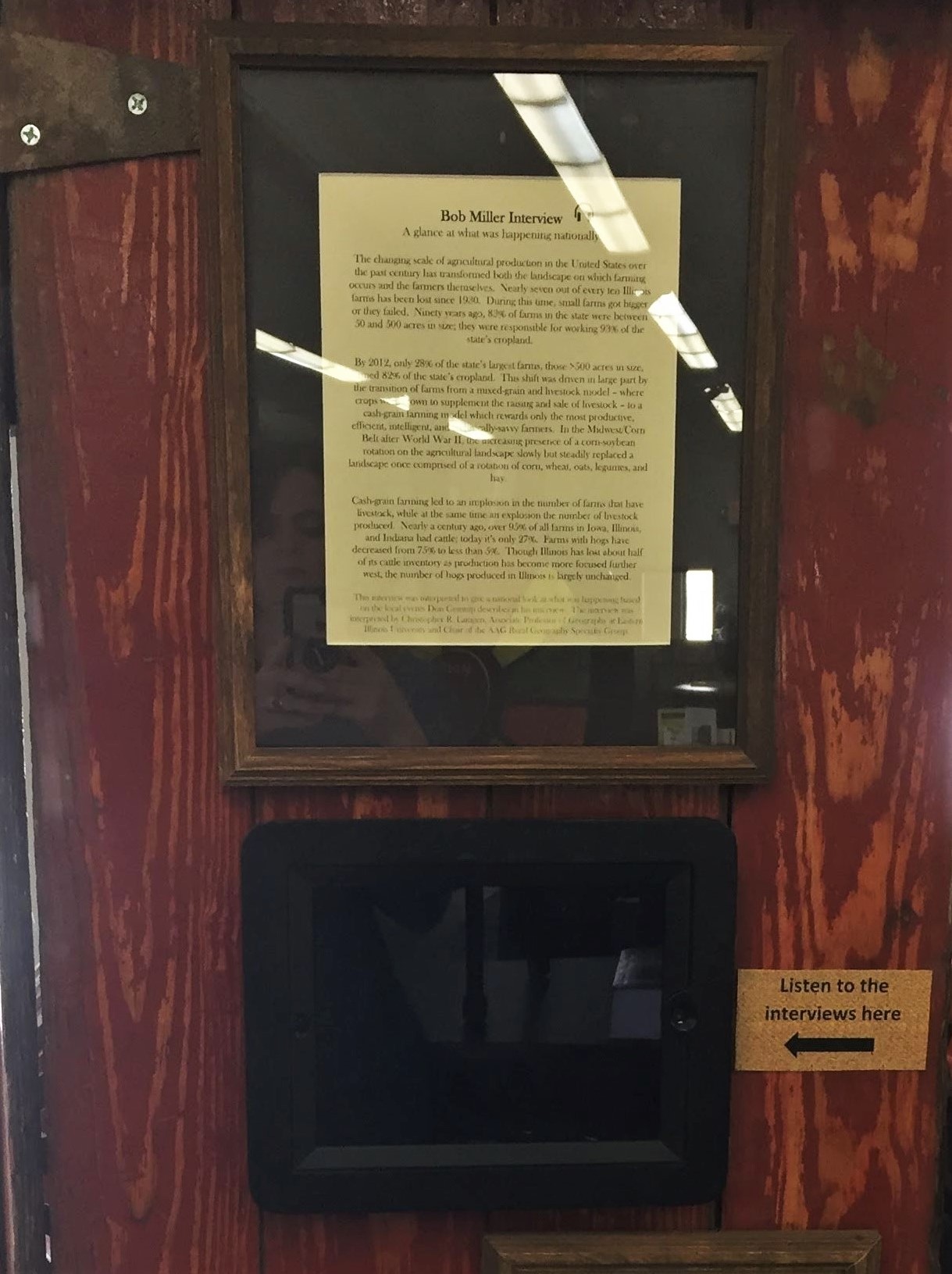

Marshall Public Library and Illinois Humanities co-hosted a workshop about documentation of rural mid-American culture in May 2018, almost a year before Crossroads visited Marshall. During that workshop, library staff and volunteers interviewed local farmers Bob Miller and Don Guinnip. Their interviews provided much of the content of the library’s companion exhibition and were added to its extensive collection of local oral histories. Audio recordings and written transcripts are available on a page devoted to Crossroads-related content on the library’s website. The exhibition also featured contextual commentaries by agricultural geographer Christopher Laingen of Eastern Illinois University that situated the histories of the Miller and Guinnip family farms in relation to broader regional and national trends.

Guinnip, age 65 at the time,[1] and Miller, then 64,[2] described the dramatic changes that have occurred on their farms from their early childhood years to the present, which are indicative of developments in agriculture that have occurred in recent decades in many parts of the lower Midwest.

“Both of the oral histories addressed how it used to be that every person they knew grew up on a farm. Every person they knew had some sort of farm animal, had a larger family,” noted Alyson Thompson, director of the library. “But as they got older, and as technology advanced and urban America grew, they began seeing these shifts from small farms that were operated by the entire family to larger farms operated by less people in the family, and that’s credited to technology, mostly, which also pushed some of those family members into urban America.”[3]

Bob Miller, whose German American ancestors arrived in Clark County by way of southwestern Indiana in the late nineteenth century, observed, “As I grew up, we always had the garden and the milk cow and the chickens and things like that, but as our farm changed with labor and began to change with technology and the new way of doing things came along, a lot of those aspects were gone.”[4]

“One of the big changes is that agriculture went to a business mindset, rather than a lifestyle. Everybody’s always envisioned that farming is a lifestyle, and it has been up to now, [to] a certain point, but now it has to be run as a business if you want it to grow and succeed,” he continued. “There’s still a place for those small family farms, but we’ve become very industrialized, and so we’ve had to change those things.” Miller explained that many of those changes relate to economies of scale: “When I got started, they would have a 100-, 150-acre, or a 200-acre farm, and they’d raise their families. Today, it just takes hundreds, if not thousands, of acres, and instead of just hundreds of heads of animals, it takes thousands, because of the margin on each one of those, and our lifestyles have changed.”[5]

“I have gone through, in my lifetime, a very much hand-labor [approach to] raising livestock to the early modernization of confinement systems, until now, my brothers and I are exiting the livestock business, because our facilities have been up for forty years, and they’re literally deteriorating,” said Miller. “My niece and nephew, they are going to come back in, and they are going to put up a huge barn that will hold about four thousand animals, and it will be a contract barn,” he added. “They are going to sell their labor to somebody else, and I think that’s the option that is going to be most feasible for them right now.”[6]

Miller began his crop-growing career with a 30-horsepower tractor and a two-bottom plow. Now, however, “the tractor that I do the planting the crops with is a 340-horsepower tractor with leather interior and air conditioning and a $3,000 light package, so late at night, when I’m out there working, it’s like there’s a little town moving through the field. We’ve also adapted all the GPS technology that not only steers the tractor, but it also runs my planter, gives me my planting population. I can increase it; I can slow it down—just so many things. Matter of fact, I’ve gone to the point, I use an iPad that the GPS signal goes to a cell-phone tower, and the cell-phone tower beams to my iPad, my iPad Bluetooths it to my tractor, and that’s how it steers itself through the field,” he explained.[7]

“It also allows me to check e-mails, text messages. I can watch the markets; I can communicate with other people; I can multitask a whole lot of things, because I’m not physically having to drive that tractor.” Miller continued, “They always said years ago, if a good corn husker could husk a hundred bushel of corn in a day by hand, he was doing really good. There’s days last fall that I harvested thirty to thirty-five thousand bushel of corn in a day.”[8]

As challenging as the raising of livestock and the growing and harvesting of crops can be, “the difficult aspect of agriculture is the business side of it, making the right decision at the right time,” Miller observed.[9]

“I’m thankful that as I started in agriculture in the early to mid-‘70s, agriculture was really good. It was still, ‘Work hard, more animals, more acres, and you do okay.’ Then, as we got into the late ‘70s, early ‘80s, interest rates come up, there was an embargo thrown on, the agriculture scene changed in a hurry, and all of a sudden, that aspect of ‘just grow, grow, grow, grow’ began to stop,” he commented. “Farmers of the next generation coming on, they probably borrowed too much, and all of a sudden, we also know what happened is, interest rates went up, and that’s where—it’s based on your cash flow, and when interest rates went up, there were a lot of young guys exited the agriculture business.”[10]

“In the last ten to twenty years, we became more of a profit-oriented center, where margins began to become squeezed more, and so you had to operate on more volume, and agriculture, like any business, is very capital-oriented, and so that kind of limits a lot of people,” Miller noted. “It’s hard to go out and just jump into agriculture on your own anymore, if not impossible to do. You have got to have a start either from a family that’s in the business, or from a gentleman that is retiring, has no offspring, and is willing to step up and to not let his lifetime of work go away and help a young person get started.”

Likewise, Don Guinnip observed, “As a twenty-five-year-old young person, to say, ‘I want to farm,’ you’ve really got a chore ahead of you, because accumulating the capital: a new combine is $250,000; a tractor is $150,000; a grain bin’s $50,000. Land has gone from four or five dollars an acre, you know, [around the year] 1900 to—the highest we got in this county is $10,000 an acre.” Guinnip added, “The university will tell you, you need twelve hundred acres, minimum, of corn and beans to support just a—that’s the minimum economic farm.”

That scenario is a far cry from the one experienced by Guinnip’s ancestors when they arrived in Clark County in 1837, having traveled from western New York by way of central Indiana. “The land office for this area was in Palestine, Illinois, and all the land was public land, so if you wanted to buy a farm or land, you had to go to Palestine,” said Guinnip. “They were subsistence farmers. They just raised enough to live on. They came here–the farm, the center part of our farm, by today’s standards, is a terrible farm. It’s just not good farm at all. It’s only half-tillable; it’s hills; it’s creek bottoms.”[11]

“They wanted good timber, free-flowing water, a lot of game, and good drainage, and where they built the log cabin was on top of a sand rock ridge, and it’s sixty feet down to the creek, and there’s two springs there, but it was heavy white oak and ash and hickory and poplar trees,” he continued. “Marshall was just being founded about the time they got here, and [they] bought a lot of land and then logged it off and sold the timber. They had a sawmill for the early buildings here in town.”[12]

The terrain of Clark County, which adjoins the Wabash River, is somewhat hillier, rockier, and more wooded than the vast, flat, fertile prairies just to the north and therefore was not as readily conducive to large-scale agriculture. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Clark County belonged more to the “general farming” region that encompassed much of southern Illinois and adjacent parts of the lower Midwest and upper South, characterized by smaller farms and a wider variety of crops and livestock, than to the Corn Belt. Consequently, commercial agricultural infrastructure did not develop quite as rapidly or extensively there as it did farther upstate.

Nonetheless, many of the developments—good, bad, or otherwise—that the Guinnips experienced seem typical of those that affected farm families throughout Illinois and beyond during that period. A member of the family sustained a debilitating injury, prompting a modification of farming practices that proved largely successful. Sadly, the family also endured several premature deaths. Dramatic price fluctuations occurred—some detrimental to the Guinnips, others beneficial.

The history of the Guinnips’ farm in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries includes participation in threshing of wheat and oats using steam-powered machinery in cooperation with other local farmers. That history highlights the crucial contributions of women, both in carrying out farm tasks and in supplementing the family’s income through off-farm work. It also reflects the influences of university extension education and the introduction of practices such as enhancing soil with lime and rock phosphate.

New Deal-era policies called for destruction of crops and livestock to counteract overproduction and price reductions. To some members of the family, those initiatives seemed disturbingly counterintuitive in light of the food shortages afflicting many cities. Consequently, the hitherto William Jennings Bryan-admiring Democrats began to gravitate toward the Republican Party. Rural electrification had myriad implications for the Guinnips, as did the advent of gasoline-powered tractors.

“Musgrave International Harvester at Gordon Junction, which is Route 1 and Route 133, they had tractors, so 1948, Grandpa went down there, and he bought an H, an M, and a C, and all the machinery to go with it,” Don Guinnip recalled. “We kept the teams of horses they used. Grandpa would harness them and tie them up at the barn there up into the mid-‘50s and parade them around. He just wouldn’t get rid of them, but they quit [using the horses in] farming. I’d say the last year they farmed with horses was ‘48. And it was all mechanized in Dad’s time.”[13]

- Don Guinnip, interview with Damian Macey, Marshall, IL, May 15, 2018, transcript available at https://www.marshallillibrary.com/media/images/pdf/oralhistory/donguinnip2.pdf. ↵

- Bob Miller, interview with Alyson Thompson, Marshall, IL, May 15, 2018, transcript available at https://www.marshallillibrary.com/media/images/pdf/oralhistory/bobmiller2.pdf. ↵

- Alyson Thompson, telephone interview with author, October 16, 2019. ↵

- Bob Miller, interview with Alyson Thompson, May 15, 2018. ↵

- Bob Miller, interview with Alyson Thompson, May 15, 2018. ↵

- Bob Miller, interview with Alyson Thompson, May 15, 2018. ↵

- Bob Miller, interview with Alyson Thompson, May 15, 2018. ↵

- Bob Miller, interview with Alyson Thompson, May 15, 2018. ↵

- Bob Miller, interview with Alyson Thompson, May 15, 2018. ↵

- Bob Miller, interview with Alyson Thompson, May 15, 2018. ↵

- Don Guinnip, interview with Damian Macey, May 15, 2018. ↵

- Don Guinnip, interview with Damian Macey, May 15, 2018. ↵

- Don Guinnip, interview with Damian Macey, May 15, 2018. ↵