Chapter 5: Fertile Ground for Agricultural Change, Part 3

The types of agricultural activity that have occurred in our state, the agricultural innovations that have occurred here, and the intersections between the two are manifold. So are the intersections between the evolution of agriculture in Illinois and the evolution of agriculture on the national and international levels, as our state’s Crossroads: Change in America host organizations made apparent.

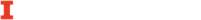

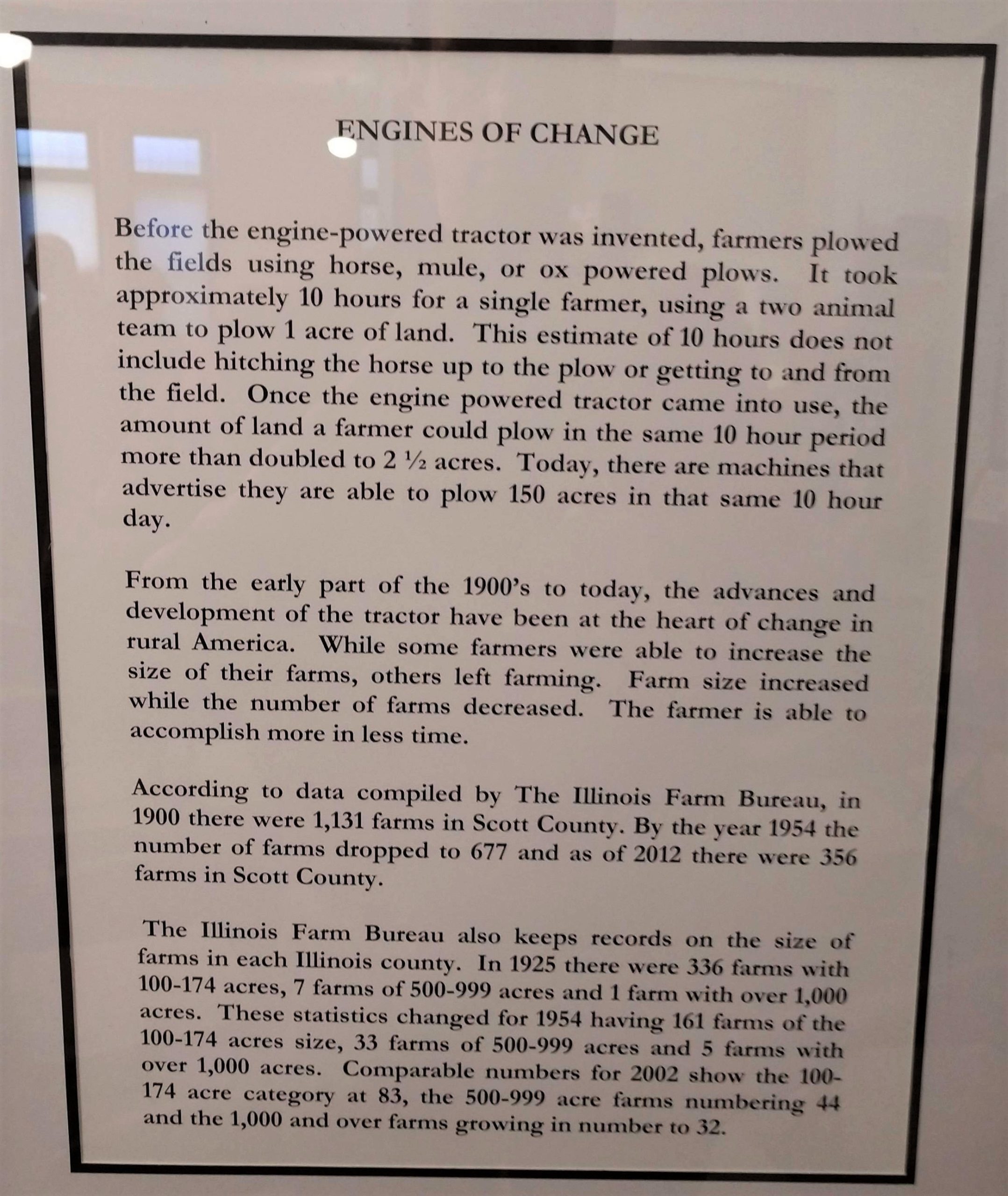

Around the same time that the Guinnip family farm in Clark County adopted gasoline-fueled tractors, so did many farmers in Scott County in west-central Illinois. The Old School Museum in Winchester examined the impact of that mid-twentieth-century trend in a section of its companion exhibition called “Engines of Change.” The text of the exhibition noted that it took approximately ten hours for one farmer to plow one acre of land with a team of two horses, mules, or oxen. With an early engine-powered tractor, the amount of land that a farmer could plow in ten hours more than doubled to two and a half acres.[1]

Consequently, “While some farmers were able to increase the size of their farms, others left farming,” the exhibition noted. “Farm size increased while the number of farms decreased. The farmer is able to accomplish more in less time. According to data compiled by the Illinois Farm Bureau, in 1900, there were 1,131 farms in Scott County. By the year 1954, the number of farms dropped to 677, and as of 2012, there were 356 farms in Scott County.”

The Old School Museum’s exhibition continued, “In 1925, there were 336 farms with 100-174 acres; seven farms of 500-999 acres; and one farm with over 1,000 acres. These statistics changed for 1954, having 161 farms of the 100-174-acre size; 33 farms of 500-999 acres; and five farms with over 1,000 acres. Comparable numbers for 2002 show the 100-174-acre category at 83; the 500-999-acre farms numbering 44; and the 1,000-acres-and-over farms growing in number to 32.”[2]

An Illinoisan whose name appeared on many of the tractors that contributed to such extensive changes visited the Old School Museum on October 28, 2018, to lead a conversation about the ongoing evolution of farming and its implications for rural communities. John Deere, portrayed by acclaimed storyteller and longtime Illinois Humanities Road Scholar Brian “Fox” Ellis, addressed the board of directors of the corporation that he founded, represented by the audience, upon the occasion of his retirement. Deere reflected on milestones in his career and their ramifications.

Those included his move from his native Vermont to the small northern Illinois community of Grand Detour in 1836 and, soon afterward, the invention and mass production of a self-scouring steel plow, which arguably made as significant an impact in the mid-1800s as the gasoline-powered tractor would a century later. Known as “The Plow that Broke the Plains,” it facilitated the cultivation of densely packed prairie soils and greatly accelerated agricultural expansion west of the Mississippi.[3]

Deere (Ellis) then encouraged the audience members to gather in small groups to discuss how current trends and potential future developments in agriculture might affect the environment, the economy, and society in rural mid-America. Those factors included many of the same ones addressed, directly or indirectly, by other Crossroads host organizations: trends toward economies of scale, capital-intensive farming, and consolidation in the agribusiness industry; innovations in agricultural technology and methods; and prospects for organic, sustainable, and niche-market farming. Participants civilly expressed a range of views as to which potential paths into the future would be most beneficial for both nature and culture in places such as Scott County.[4]

Still another place where agriculture and community life are thoroughly intertwined is the small town of Atlanta in central Illinois, where the Atlanta Museum hosted Crossroads: Change in Rural America in February and March 2018. The significance of agriculture as a component of the community’s identity is a prominent theme in “Prairie Pathways,” a mural that Atlanta-area residents collaboratively created. Designed by Regan King, an artist based in Bloomington, Illinois, with substantial community input, the mural features depictions of the expansive corn and soybean fields that surround Atlanta. It also includes references to the Atlanta Fair, an agricultural celebration and antecedent of the present-day Atlanta Fall Festival, as well as the J.H. Hawes Elevator, a former commercial grain storage facility.[5] The only fully restored wooden grain elevator in Illinois, it serves as an interpretive center, enabling visitors to learn about not only the mechanics of the facility but also the role of agricultural commerce in local culture in the early twentieth century.[6]

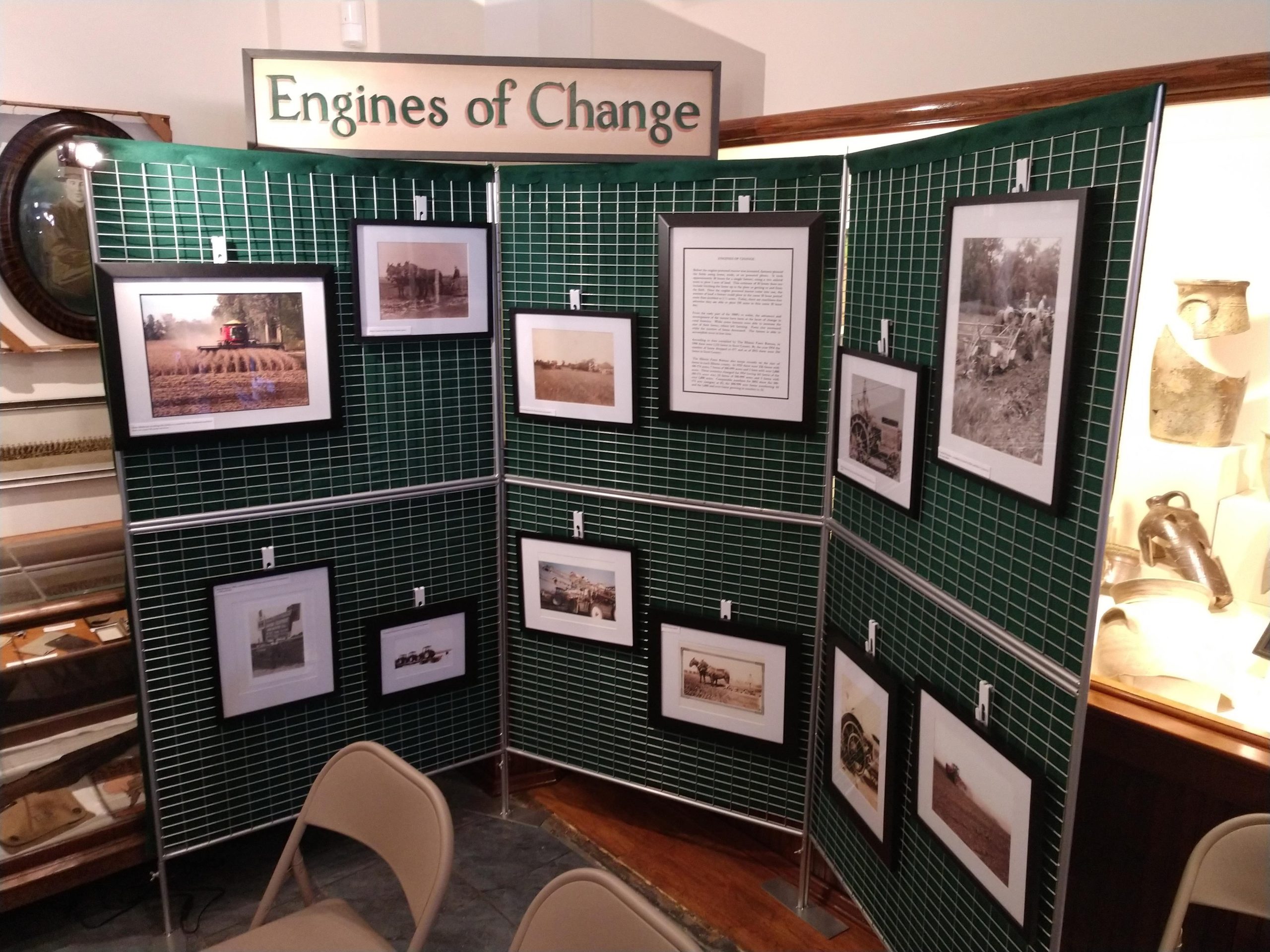

Food-production practices of yesteryear and the social contexts surrounding them were also the topic of a section of Chester Public Library’s companion exhibition that was contributed by Les Amis du Fort de Chartres (The Friends of Fort de Chartres), an organization that supports activity at Fort de Chartres State Historic Site.[7] The exhibition segment described how habitants of Chartres, a French colonial village established in 1722 approximately twenty miles up the Mississippi from Kaskaskia, grew crops and raised livestock for both local consumption and commercial sale.[8]

Much of the content was drawn from Tom Willcockson’s French Colonial Fort de Chartres: A Journey in Time, an illustrated book written with middle school-age readers in mind; it was commissioned and published by Les Amis du Fort de Chartres in 2018 with support from an Illinois Humanities “Forgotten Illinois 200” grant. The book and the exhibition segment noted that many of the village’s houses stood on lots that were enclosed by stockade fences and contained vegetable gardens, small fruit-tree orchards, wells, bread ovens, stables, and pens for chickens and pigs.

Willcockson’s text explains, “To the north of the village was a large enclosed common field of long-lot strips running back towards the bluff line. Here, habitant men and their slaves cultivated oats and hay and corn, but the main crop was wheat. The climate in the Middle Mississippi Valley was perfect for wheat, and the habitants grew enormous quantities. In spring, beginning on a date set by the village meeting, each habitant was required to repair a portion of the long fence that enclosed the common field, and then any stray animals were driven out. The fields were prepared with medieval-style wheeled plows, and once the wheat was planted, it didn’t require much care until it was harvested later in the summer using hand scythes. Harvested wheat could be ground into flour at one of the local mills in the parish of Ste. Anne.”[9]

Willcockson continues, “Scrubland outside the village was used as a commons to keep livestock, including many hogs which freely roamed the streets and had to be kept out of the enclosures and the common field. Besides flour, the Illinois country shipped great quantities of salted pork to New Orleans.”[10]

Transporting flour milled from locally grown wheat southward via the Mississippi River and subsequently other routes has been an important economic activity in Randolph County throughout much of its history. The H.C. Cole Milling Company in Chester and its multifaceted legacy were featured in a portion of Chester Public Library’s companion exhibition. One of the most prominent families in the region during much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Coles migrated from the Finger Lakes region of New York to St. Louis and then to Randolph County, where they purchased a large amount of land and established a sawmill with a corn-grinding attachment in 1837, followed by a wheat flour mill along the Mississippi in 1839.[11] According to an article published in Modern Miller in 1906, “The Coles were pioneers in the milling trade of the west, and the milling industry established by the first generation has thrived and continues one of the most successful in Illinois.”[12]

Charles Briggs Cole, who was a partner in the mill and involved in its management for several decades beginning in 1868, often receives credit for much of its success. During his tenure, the mill purchased one of the first electricity generators in the region and used the surplus power to provide electric streetlights for Chester before most other communities in the United States, even many major cities, had them. The generator is now owned by The Henry Ford in Michigan, where, coincidentally, Debra Reid, a native of the Chester area and one of the two curators of Crossroads, is employed.

Charles Briggs Cole was also a railroad entrepreneur, a state legislator affiliated with the economically conservative wing of the Democratic party, and an influential civic leader. He was E.C. Segar’s inspiration for the character of Cole Oyl in the Popeye comics. He funded the construction of Chester Public Library and died almost immediately after it was completed in 1928. His funeral was the first public event held in the library.[13]

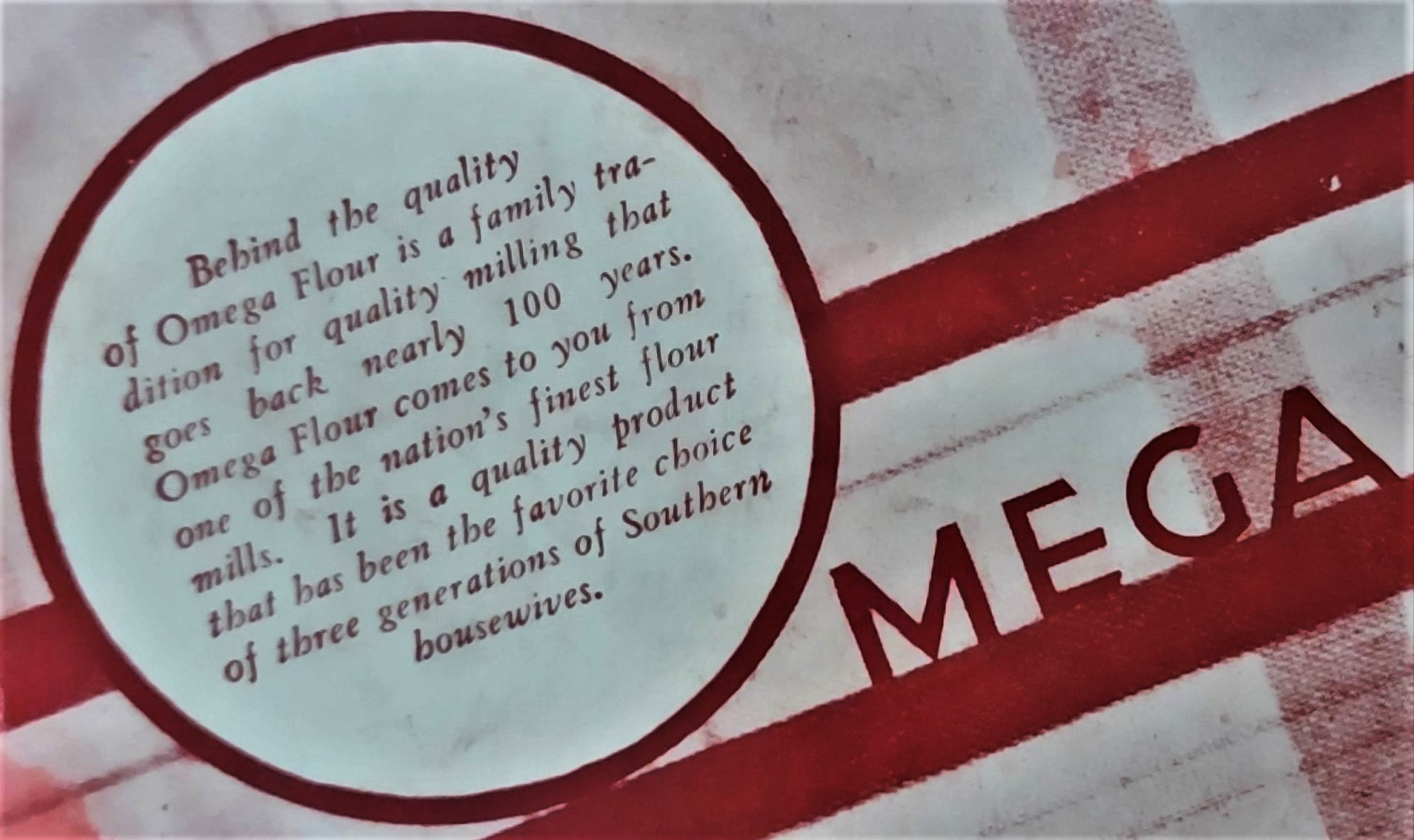

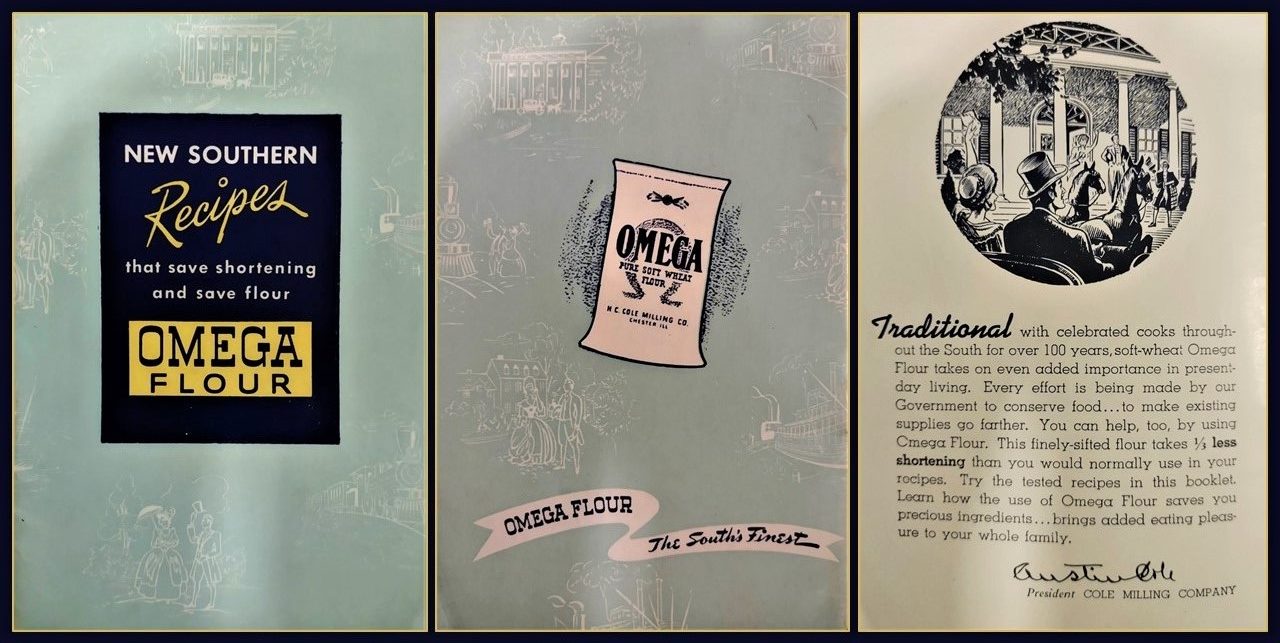

The H.C. Cole Milling Company remained in the family for four more decades, producing flour under several brand names, notably including Omega. Distributed mostly (though not exclusively) to locations south of its point of origin, Omega was marketed as “The South’s Finest Flour,” and its packaging and promotional materials often featured Southern iconography (sometimes including plantation imagery that would be considered racially insensitive today).[14]

In 1970, Tennessee-based Martha White Foods purchased the mill,[15] which was acquired two years later by ConAgra, then based in Nebraska.[16] Still in operation as of 2021, the facility is owned by Ardent Mills, a ConAgra affiliate.[17]

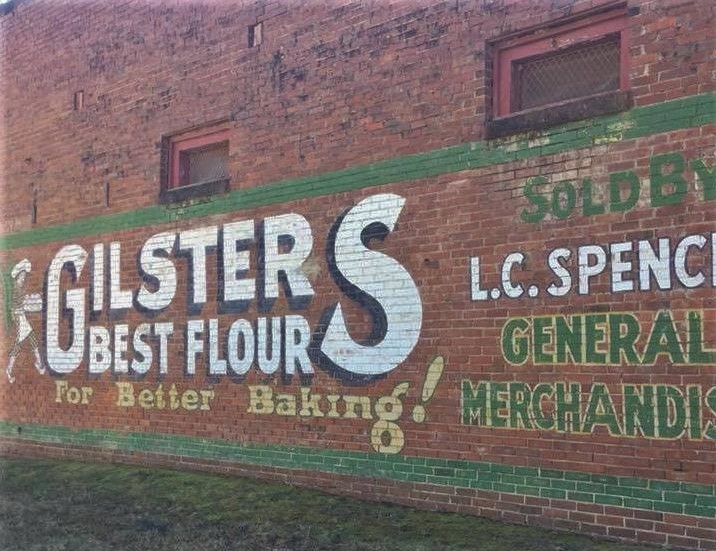

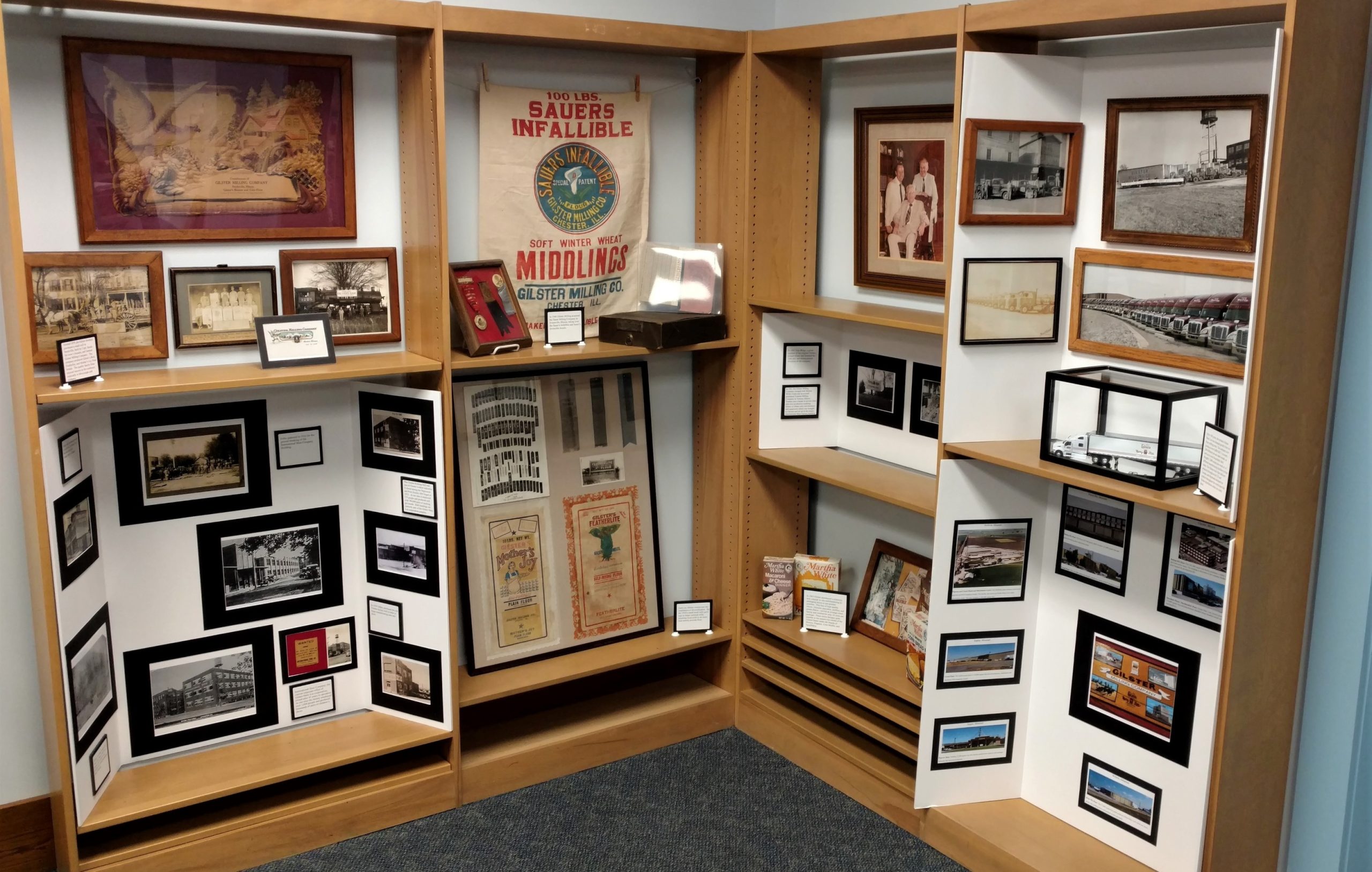

Like the Cole family’s enterprise, the Gilster-Mary Lee Corporation began as a family-owned flour mill. Originally called the Gilster Milling Company, it began operation in 1895 in nearby Steeleville. Also like the Coles, the Gilsters marketed their flour predominantly in the Southern states.[18] (Painted advertisements for Gilster’s Best Flour still appear on the sides of general store buildings in the rural Mississippi communities of McCarley[19] and Morgan City.[20])

In the mid-twentieth century, the company began manufacturing items such as private-label cake mixes, drink mixes, and potato products and expanded its operations to Chester. During much of the 1960s, Gilster was affiliated with Martha White Foods. In the following decade, Gilster merged with Mary Lee Packaging, a company that had broken away from Gilster several years prior.

Gilster-Mary Lee has since expanded significantly, constructing or acquiring plants in several communities throughout Illinois, Missouri, and other states.[21] It is now a nationally consequential processor of private-label packaged foods and a major employer in southwestern Illinois.[22] The company contributed funding and supplies for Chester Public Library’s companion exhibition and was featured in it. (Sadly, a year and a half after the library hosted Crossroads, longtime Gilster-Mary Lee President Don Welge became the first Randolph County resident to die of COVID-19.)[23]

The agricultural content of Chester Public Library’s companion exhibition also included an original documentary film about three families whose farming practices illustrate the breadth of current agricultural activity in Randolph County: the Vasquezes, who are among the largest landowners in the region and practice capital-intensive row-crop farming; the Stallmans, who produce wheat, corn, soybeans, and beef cattle on their centennial farm and are active in the Illinois Farm Bureau; and the Schoenbecks, who grow pumpkins and host agritourism activities, including horseback riding, corn mazes, and fall festivals.[24]

Although some characteristics of agriculture in Illinois have persisted since the French colonial era, the magnitude of the changes that have occurred between then and now seems astounding, even when one considers that they manifested themselves over a period of three centuries. Many of those developments resulted, at least in part, from technological innovations that emerged from places such as Shelby and DeKalb counties, and many are evident in the stories of the Guinnips, Millers, Vasquezes, Stallmans, Schoenbecks, and countless other farming families from Scott County, Logan County, and other locations throughout our state. Of course, those changes did not happen in a vacuum.

- Companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, Old School Museum, Winchester, IL, October 27-December 8, 2018. ↵

- Companion exhibition, Old School Museum. ↵

- “John Deere,” John Deere (Deere & Company), https://www.deere.com/en/our-company/history/john-deere/, accessed April 1, 2023; “John Deere, Vermont Blacksmith, Breaks the Plains,” New England Historical Society (website), https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/john-deere-flees-vermont-make-fortune-prairie/, accessed April 1, 2023. ↵

- Brian “Fox” Ellis, presentation and discussion, Old School Museum, Winchester, IL, October 28, 2018. ↵

- Catherine Maciariello, telephone interview with author, October 23, 2019. ↵

- “J.H. Hawes Grain Elevator & Museum,” Destination Logan County, Logan County Tourism Bureau (website), https://destinationlogancountyil.com/grain-elevator-museum, accessed April 1, 2023. ↵

- “Les Amis du Fort de Chartres,” Fort de Chartres State Historic Site (website), http://www.fortdechartres.us/les-amis-du-fort-de-chartres/, accessed April 1, 2023. ↵

- Tom Willcockson, French Colonial Fort de Chartres: A Journey in Time (Prairie du Rocher, IL: Les Amis du Fort de Chartres, 2018), 12-15. ↵

- Willcockson, French Colonial Fort de Chartres, 13. ↵

- Willcockson, French Colonial Fort de Chartres, 13. ↵

- “Charles B. Cole and Alice E. Cole,” The Randolph Society (website), https://randolphsociety.org/charles-b-cole-and-alice-e-cole/, accessed April 1, 2023; “History of Chester,” City of Chester, Illinois (website), http://chesterill.com/about/history-of-chester/, accessed April 1, 2023; George Washington Smith, A History of Southern Illinois: A Narrative Account of its Historical Progress, its People, and its Principal Interests, Volume 3 (Chicago and New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1912), 1248-1250. ↵

- “Pioneer Millers of Illinois,” Modern Miller 32, no. 9 (March 3, 1906): 16. ↵

- “Charles B. Cole and Alice E. Cole,” The Randolph Society; “History of Chester,” City of Chester, Illinois; Smith, A History of Southern Illinois, 1248-1250. ↵

- “32 Tested and Approved Recipes Especially Prepared for Omega Flour,” (Chester, IL: H.C. Cole Milling Company, publication date not indicated); “Charles B. Cole and Alice E. Cole,” The Randolph Society website; “Omega Flour: Tested Recipes for Cakes, Pastries and Hot Breads” (Chester, IL: Omega Flour, publication date not indicated); a search on “Omega Flour” on the “Newspapers.com” website indicates that the product was marketed predominantly in Southern states. ↵

- “Martha White Foods Acquires Cole Milling,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 16, 1970, 5C. ↵

- “Chester Mill Sold,” The Southern Illinoisan (Carbondale, IL), February 2, 1972, 1. ↵

- “Chester Mill,” Ardent Mills (website), date accessed or published https://www.ardentmills.com/our-facilities/illinois/chester-mill/. ↵

- “Our History,” Gilster-Mary Lee Corporation (website), http://www.gilstermarylee.com/about-us/our-history, accessed April 1, 2023. ↵

- “McCarley, MS,” Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/McCarley-MS-213988985281962/, accessed April 1, 2023. ↵

- Andrew Morang, “The Mississippi Delta 23: Morgan City,” Urban Decay (blog), August 19, 2017, https://worldofdecay.blogspot.com/2017/08/the-mississippi-delta-23-morgan-city.html. ↵

- “Our History,” Gilster-Mary Lee Corporation. ↵

- “Top 150 2017: No. 29t Gilster-Mary Lee Corp.,” St. Louis Business Journal, March 24, 2017, https://www.bizjournals.com/stlouis/news/2017/03/24/top-150-2017-no-29t-gilster-mary-lee-corp.html. ↵

- Pan Demetrakakes, “Gilster Mary-Lee CEO Dies of COVID-19,” Food Processing: The Information Source for Food and Beverage Manufacturers, April 21, 2020, https://www.foodprocessing.com/industrynews/2020/gilster-mary-lee-ceo-dies-of-covid-19/. ↵

- Documentary video, companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, Chester Public Library, Chester, IL, September 8-October 20, 2018. ↵