Introduction: What’s Included?

What does “rural America” include?

Crossroads: Change in Rural America examines the ongoing environmental, economic, social, and cultural evolution of rural places within the United States–but what, exactly, makes a place “rural”? As the exhibition itself notes, that adjective is notoriously difficult to define precisely and to everyone’s satisfaction. Its meaning remains a subject of debate among scholars, policymakers, and professionals in a wide variety of fields, as well as residents of places that might (or might not) be described as “rural.”

For instance, as of 2008, more than two dozen definitions of “rural” were officially in use among federal agencies, according to a USDA Economic Research Service publication by John Cromartie and Shawn Bucholtz.[1] Furthermore, in his preface to the first edition of his influential survey, Born in the Country: A History of Rural America (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), David Danbom notes, “While the title promises a study of rural America, what the book delivers is mainly a study of farm people in America,” adding, “I believe that farm living is enough different from small-town living that the two are not easily or valuably integrated into a synthetic treatment.”[2]

At least two reviewers of Born in the Country, however, though generally highly complimentary of the book, criticize Danbom’s decision to focus so predominantly on agricultural life (or to designate what is primarily a history of agricultural life in America as a history of “rural America”). Thus, they imply that rural America encompasses more than agrarian America. Mark Friedberger comments, “Given his analytical talents and broad grasp of the subject matter, it is unfortunate that Danbom decided not to tackle the history of rural America from the perspective of the non-farm population. Although most rural Americans lived on farms in the nineteenth century, enough research has been done to generalize about proto-industrialization, commercial fishing, farm-town relations, the impact of what geographers call ‘agro-industry,’ the importance of a large white mobile laboring underclass in the antebellum South, and the dynamics of the small town and village.”[3] Similarly, Timothy Collins observes, “The problem with Danbom’s approach, with its focus mainly on agriculture, is that it reinforces the old stereotype ‘rural equals agriculture’ that has crippled the evolution of rural development policy for several generations.”[4] The contrast between the conceptions of rurality represented by Danbom on one hand and Friedberger and Collins on the other also manifested itself in conjunction with the Illinois tour of Crossroads: Change in Rural America, especially in relation to this question: Should “rural” be applied exclusively to unincorporated areas, or may small towns located in relatively sparsely populated areas legitimately be considered “rural”?

Kay Rippelmeyer-Tippy, who was then Illinois Humanities’ programmatic field representative in southern Illinois and whom I greatly respect, contributed significantly to the planning and execution of our Crossroads tour. She understood “rural” to apply specifically to unincorporated places.

Rippelmeyer-Tippy was raised on a farm near Valmeyer in Monroe County, Illinois, and has lived most of her adult life on property adjoining the Shawnee National Forest in Jackson County. The author of two books about the Civilian Conservation Corps’ activities in southern Illinois and the experiences of participants in that program,[5] she has written extensively about many facets of the environmental, economic, and social histories of rural mid-America.

Rippelmeyer-Tippy is accustomed to using “rural” to designate unincorporated areas and perhaps very small communities that developed around crossroads, mills, churches, or schoolhouses, for example, but not anything that would ordinarily be considered a town. In her view, the differences between residing in a small town—even one as small as Atlanta, Illinois, population 2,000—and living in the country remain substantial enough to warrant classifying those experiences under separate rubrics. Furthermore, she associates the term “rural” with making a living from the land through activities such as farming, foraging, hunting, and harvesting timber.[6]

I, however, am accustomed to conceptions of “rural America” that encompass small towns in addition to the countryside. I was raised near Chester, a small community in southwestern Illinois that figured prominently in our statewide tour of Crossroads. My interest in rural American culture has influenced much of my professional activity in public humanities, public folklore, and related fields. Although the discourses with which I am familiar usually acknowledge that there are important experiential and social distinctions between residents of small towns and residents of surrounding unincorporated places, most indicate (or at least imply) that both belong within the category called “rural.”[7]

While it remains true that small towns and unincorporated areas represent distinct subcategories within that category, the cultural differences between them arguably have diminished in recent decades because of many of the very changes that Crossroads and its Illinois host organizations’ companion exhibitions examined: school consolidation, agricultural consolidation, and innovations in transportation and communications technology, for example.

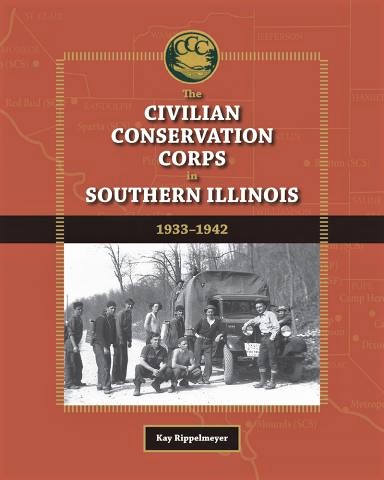

During the early stages of preparation for the Illinois tour of Crossroads: Change in Rural America, the contrast between Rippelmeyer-Tippy’s and my interpretations of the operative adjective occasionally caused confusion and honest misunderstandings, both between the two of us and between us and members of host organizations who were beginning to plan their companion exhibitions and programs. For instance, I remember one conversation in which I described coal mining as a quintessentially rural occupation, while Rippelmeyer-Tippy argued that coal mining is not rural and, in fact, represents a divergence from rural life. In another discussion, I expressed support for a host organization’s preliminary plan to examine the evolution of architectural styles in a small town, but Rippelmeyer-Tippy questioned whether that topic was sufficiently consistent with the theme of rurality to be appropriate for a Crossroads companion exhibition.

Once I realized that the inadvertent miscommunication stemmed from the difference between Rippelmeyer-Tippy’s and my interpretations of “rural,” I invited Rippelmeyer-Tippy to provide her definition of that word and to share it with representatives of the host organizations, along with my own, during the orientation workshop for the tour. Rippelmeyer-Tippy offered this definition of “rural,” resembling the one implied by Danbom: “as substantiated by the Oxford English Dictionary, the American Heritage Dictionary, and the Readers’ Digest Great Encyclopedic Dictionary: pertaining to country life as opposed to town life; engaged in country occupations, especially agricultural or pastoral; of or relating to farming, agricultural; contrasting with urban; applicable to sparsely settled or agricultural country, as distinct from settled communities.”

In contrast, I defined “rural America” as follows, echoing Friedberger and Collins (at least in some respects): “collectively, those places within the United States that are relatively sparsely populated, encompassing both unincorporated areas and small towns, in which local natural features and the use of those features by people contribute directly and significantly to the local economic base and cultural identity, and in which folk culture constitutes a significant proportion of the local culture.” (I added several footnotes in which I qualified or expounded on terms included in my definition.)

During the orientation workshop for the Illinois tour of Crossroads, Rippelmeyer-Tippy gave a presentation in which she encouraged the host organizations to view their participation as a rare opportunity to present companion exhibitions and programs concentrating specifically on aspects of country life and agrarian culture. Drawing upon her impressive knowledge of such subject matter, she discussed a wide variety of potential topics: activities that often involved pooling of labor, such as barn raising, threshing, hay baling, and quilting; the many vital roles of women in farm life; the evolution of agricultural public policy and activism; and social institutions such as 4-H clubs, Farm Bureau chapters, churches, and county fairs, among others.[8]

Although most of the host organizations’ companion exhibitions reflected a broader conception of rurality that encompassed small-town life, several of the host organizations did modify their plans in light of Rippelmeyer-Tippy’s recommendations, focusing more substantially on topics particular to unincorporated places and agrarian culture than they had originally intended.

Similarly, the Smithsonian-produced Crossroads exhibition itself reflects a supposition that “rural America” includes small towns, at least in some instances, but it, too, devotes a large share of its attention specifically to life in the country.

What does Crossroads: Change in Rural America include?

Crossroads: Change in Rural America, which remains on tour in several states as of this writing, consists of six main sections, organized thematically:

Introduction

The exhibition begins by establishing “crossroads” as a metaphor for various facets of rural American life. One is the centrality of place and the influence of a location’s environmental and physical traits upon the character of human activity there. Another is the contestation and, in some instances, the eventual synthesis of contrasting views regarding the essential characteristics of human activity in a given rural place: different ethics of land use and resource allocation; disparate conceptions of community, equity, and liberty. Still another is the intersection of a rural place’s past and its future. How will the former influence the latter? What, and who, will determine the answer to that question? The “crossroads” metaphor might also be applied to the relationship between the identity of rural America and that of America in general.

The introduction to Crossroads invites viewers to ponder how education, access to services, commerce, agriculture, infrastructure, and demographics have contributed to change in rural America and to the evolution of its relationship to the United States as a whole over the past century. “Where people meet, ideas intersect, and change is constant,” the exhibition text observes.[9]

Identity

Myriad factors contribute to the identity of rural America, of which there are myriad variants. In centuries past, some people imagined it to be a frontier where civilization could begin anew, while others regarded it as a frontier that offered refuge from civilization. For some, it has been a place of boundless freedom and unlimited opportunities to pursue self-definition and self-actualization. For others—including Native Americans, enslaved Africans and their descendants, immigrants, and economically disadvantaged residents—it has too often been precisely the opposite.

The “Identity” section of Crossroads examines how the arts have influenced conceptions of rural America in the popular imagination. This portion of the exhibition features paintings, photographs, music, and books that represent rural American artistic traditions or interpret various aspects of rural American culture from a wide range of perspectives. These include images created by Winslow Homer and Currier and Ives; a Navajo blanket and an African American quilt; photographs of Americans at work in rural settings from Georgia to Missouri to Washington; and such place-based songs as “Home on the Range” by Brewster M. Higley and “Nutbush City Limits” by Tina Turner.

The “Identity” section of the exhibition also raises the question of how different individuals and institutions define the terms “rural” and “rural America” and what those words connote in various people’s minds. Additionally, this section considers how rural Americans’ occupations and livelihoods relate to their geographic settings, resource bases, and cultural identities. “It can be a hard life,” the exhibition text remarks. “Why would someone choose to stay? Love of the land. Community spirit. Persistence and commitment. Family and personal relationships. These are just a few of the many motivations that have helped rural and small-town Americans maintain resilience in the face of uneven opportunity.”[10]

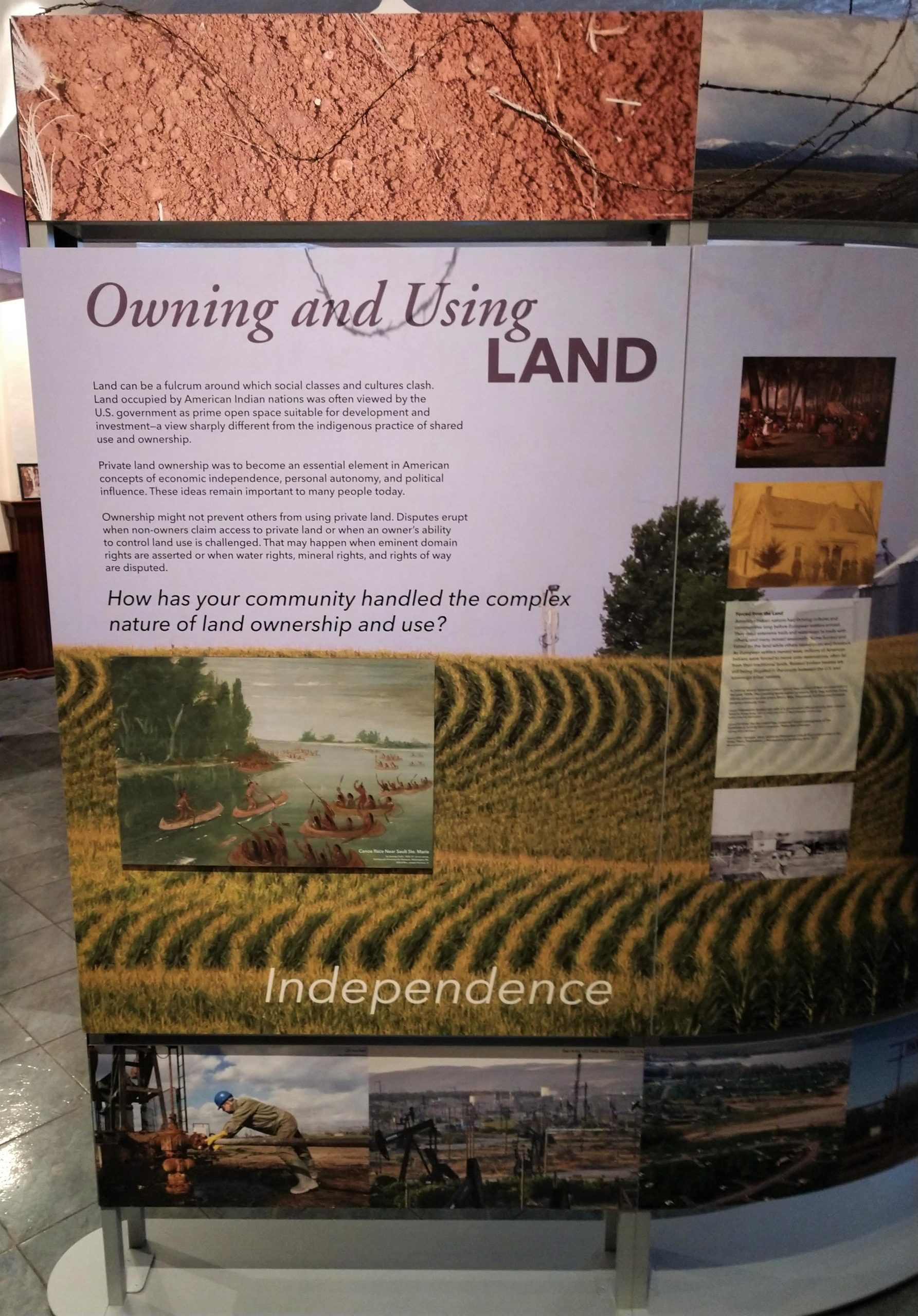

Land

Land is an essential theme in rural American life, past and present, for reasons too numerous to mention. The third main section of Crossroads mentions a good many of them, nevertheless. People who have lived in rural America over the centuries have held widely disparate views as to whether land can be owned and, if so, how ownership should be determined, as well as how land ought to be used and managed and what conscientious stewardship of land requires. The philosophical differences between Native Americans and Europeans about such matters in the decades following the latter’s arrival on these shores were especially pronounced, but disagreements among European Americans also occurred with some frequency (and still do). According to a prominent tradition in American thought, private ownership of land facilitates independence, but not all rural Americans agree. Conversely, many rural Americans value publicly owned land and associate it with such virtues as equity and accessibility, while others consider it a manifestation of governmental intrusion. Conflicts over land ownership, use, stewardship, and access punctuate rural American history. As the exhibition text says, “Nothing stirs passions like different ideas about land and access.”[11]

The terrain and natural features of any given rural landscape contribute significantly to its residents’ sense of place and local identity. The harvesting of animals, vegetables, and minerals from the land has been central to rural American life throughout its history, and land is the medium of agriculture, arguably the quintessential rural American vocation.

The “Land” section of the exhibition provides numerous examples and illustrations of all of these trends and themes. It features recordings of cackling hens and rushing streams; stories of a Hmong immigrant livestock producer in Arkansas and a landscape artist in Wyoming; discussion of the cession of lands in present-day Indiana in the early nineteenth century by Miami, Wea, Potawatomi, Eel River, and Delaware people in response to encroachment and coercion (whether implicit or explicit) by white settlers; and photographs of subjects ranging from a wheat field in Kansas to canoeists in New Hampshire, from coal miners in Pennsylvania to sharecroppers in Mississippi, from a demonstration against Bureau of Land Management policies in Nevada to a demonstration against construction of an oil pipeline near sites sacred to Standing Rock Sioux people in North Dakota.

“A sense of place exerts a powerful, almost spiritual, hold on many rural people. Even if they leave, it draws them back, sometimes to stay,” the exhibition text comments. “But a sense of place is not always a positive feeling. For some, rural life leaves memories of isolation, exclusion, and hard, unsatisfying work.”[12]

Community

The fourth main section of Crossroads examines the development of communities in rural America in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—whether small towns that were intentionally planned and constructed as such or communities that evolved organically as residences and businesses gradually coalesced around a locus of activity such as a stagecoach stop, schoolhouse, courthouse, or crossroads. “They formed around agricultural industries like milling and fishing, extractive industries like mining and logging, or along transportation arteries like railroads,” the exhibition text notes.[13]

This section of the exhibition highlights the bonds of fellowship fostered and sustained by community gatherings such as parades, fairs, sporting events, church services, picnics and homecomings, meetings of civic and fraternal organizations, and conversations at general stores and gas stations. It describes the evolution of local businesses, institutions, main streets, and downtowns in rural communities in locations ranging from Iowa to South Carolina to Arizona. Viewers are invited to contemplate what kinds of services and facilities they would wish to include in a rural community if they could choose only a few: A bank? A hardware store? A hospital? A library? A vegetable stand?

The efforts of rural communities to ensure their long-term viability through infrastructure construction and economic development in the early twentieth century were augmented and, in some cases, transformed by the New Deal programs initiated by the federal government in the 1930s. These included the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Works Progress Administration, and the profoundly influential Rural Electrification Administration. “Sustaining communities in rural America became a national project,” the exhibition text explains. “Efforts worked best when they meshed with the ideas and intentions of rural people, and when rural people were involved in the process.”[14]

In the middle decades of the twentieth century, rural economies changed dramatically and rapidly as highways made transportation easier and faster, benefiting some small communities while bypassing others. Mechanization reduced the need for agricultural labor. Industries and manufacturing of goods ranging from textiles to auto parts boomed, then declined, leaving some rural communities in dire straits during the last quarter of the century. Concurrently, rural America’s social fabric changed as school consolidation, immigration, the Civil Rights Movement, the counterculture of the 1960s, and efforts to reduce inequality and poverty intersected with rural American culture(s) in various ways and elicited a wide variety of responses from rural Americans.

This section of Crossroads features numerous images illustrating the evolution of community life in rural America during the twentieth century: construction of a road in Alabama and of a school in Wisconsin; 4-H members exhibiting livestock in Texas and Civilian Conservation Corps members creating a firebreak in Idaho; telephone-line installation in Tennessee and power-line installation in Wisconsin; a National Farmworkers Association march in California and a march in support of rural hospitals in Washington, DC; a closed furniture store in Nebraska and a shuttered railroad depot in West Virginia; a county convention of the Freedom Democratic Party in Mississippi and a community meeting of Native people in Alaska.

“In many communities, rural people shared ideas, worked toward common goals, and built toward a common future. Events of the twentieth century affected crossroads communities significantly: Some disappeared, many diminished, but some found new ways to thrive,” says the exhibition text.[15]

Persistence

The socioeconomic changes and challenges that have confronted rural America in recent decades have been daunting, but many of its residents and communities have responded with creativity and tenacity. Some farmers have aligned their work more closely with agribusiness and sought to become more efficient through vertical integration or capital intensification, while others have pursued organic, niche-market, or community-supported agriculture of one kind or another. Many rely at least as much on off-farm work as on agricultural work for income. Partnerships involving local business owners, local governments, civic and cultural organizations, and regional planning and development agencies, as well as programs such as the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Main Street America, have helped to sustain activity in rural-community downtowns. Many small towns and rural counties have drawn upon their local histories, folkways, and artistic traditions to generate economic opportunity, enhance their quality of life, and attract visitors and residents. In some cases, such communities have capitalized on the curiosity about rural life that popular culture and the entertainment industry have generated while defying or complicating the stereotypes of rural Americans that they often purvey.

Examples cited in this section of Crossroads include communities in Minnesota and Nebraska where story-collecting initiatives have contributed to festivals, more nuanced interpretations of local history in the public sphere, and better-informed long-range planning, as well as small towns in New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Georgia where activities such as shearing sheep and spinning yarn from the wool, making pottery from locally sourced clay, and producing a play based on regional folk narratives have contributed to tourism and economic development while also sustaining place-based traditions. Some rural communities also sustain themselves by offering amenities to outdoor recreational tourists, such as hunters, fishers, bicyclists, and hikers; by promoting agritourism; and by appealing to people seeking tranquil places to raise their families or to live in retirement. Additional illustrations included in the “Persistence” section depict farmers and food makers at work in Minnesota, Indiana, and Vermont, as well as small-town commerce and tourism in Maine, Virginia, Ohio, and Wyoming.[16]

Managing change

“Core ideals of community, equality, opportunity, civility, and human rights stand side-by-side with American commitment to personal liberty, free markets, innovation, and economic progress. There is inherent tension between all of these values; change can cast those tensions into high relief,” the exhibition text comments.[17]

The last main section of Crossroads examines how twenty-first-century rural Americans endeavor to manage ongoing change in many of the aspects of their culture(s) discussed in preceding portions of the exhibition: identity, land, community, and persistence. This section poses questions such as “What land use and conservation issues are you currently facing in your community?” and “How can residents, different cultural constituencies, local businesses, and governments work together to help communities remain in control of their own development?”[18] This portion of the exhibition features illustrations of agricultural change management from Illinois, Wisconsin, and California; cultural change management from Texas and North Dakota; and infrastructural change management from Kentucky and Oklahoma.

The concluding component of the exhibition invites viewers to use postcards to respond to these questions: “What do you think is your town’s best asset, and how can it help sustain your community? What does your area need most? What would most benefit young people? What do you think is the most important issue facing your town that people need to discuss?”[19] The text encourages the respondents to place their postcards in a mailbox. The local host organization retrieves the cards and can share them with local officials or make them a basis for public discussions.[20]

All six sections of Crossroads: Change in Rural America address themes and topics relevant to rural Illinois. The Illinois host organizations’ companion exhibitions and public programs cogently illustrated both the particularities of life in rural Illinois and its parallels with rural America as a whole.

What does “A Bicentennial Crossroads: 200 Years of Continuity and Change in Rural Illinois” include—and how is it organized?

This commentary on the Illinois tour of Crossroads: Change in Rural America in Pressbooks form consists of two main sections followed by a conclusion. The first main section, which is the longer of the two by a large margin, encompasses chapters 1-11. It discusses and attempts to contextualize topics and issues addressed by the Crossroads host organizations’ companion exhibitions and public programs, emphasizing thematic connections among them. The other principal section, consisting of chapters 12-15, examines, in a quasi-ethnographic way, how the host organizations’ implementation of their Crossroads-related activities illustrated and responded to ongoing change in rural Illinois. Chapter 16, the conclusion, synthesizes and reflects upon the contents of the two main sections.

The two principal sections of “A Bicentennial Crossroads” correspond to two audiences to whom I hope the essay will be useful. One consists of scholars and educators in history and related disciplines who seek examples of local developments and trends in rural Illinois that have reflected or contributed to broader regional and national ones, as well as illustrations of the relationship between continuity and change drawn from the histories of rural places in Illinois. The other audience includes people who are interested in institutional cultural activity in early-twenty-first-century rural Illinois and its relationship to its social contexts, whether as practitioners (e.g., museum and library professionals) or as students of cultural and social dynamics (e.g., anthropologists, folklorists, and sociologists).

- John Cromartie and Shawn Bucholtz, “Defining the ‘Rural’ in Rural America,” Amber Waves, June 1, 2008, https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2008/june/defining-the-rural-in-rural-america/. ↵

- David Danbom, Born in the Country: A History of Rural America, 3rd ed. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017), 17. ↵

- Mark Friedberger, review of Born in the Country: A History of Rural America by David Danbom (1st ed.), H-Rural, H-Net Reviews, September 1996, https://networks.h-net.org/node/16806/reviews/18635/friedberger-danbom-born-country-history-rural-america. ↵

- Timothy Collins, review of Born in the Country: A History of Rural America by David Danbom (2nd ed.), Community Development 40, no. 3 (August 2009): 293-294. ↵

- Kay Rippelmeyer, Civilian Conservation Corps in Southern Illinois, 1933-1942 (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2015) and Kay Rippelmeyer, Giant City State Park and the Civilian Conservation Corps: A History in Words and Pictures (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2010). ↵

- Kay Rippelmeyer-Tippy, informal conversations with author, 2018-19. ↵

- The academic disciplines and professional fields with which Matt Meacham is most engaged include folklore, musicology, journalism, higher education, public humanities, and the activities of cultural and other nonprofit organizations. In current discourses within those fields, “rural” is often used to describe both unincorporated places and small towns in relatively sparsely populated areas, but there are certainly exceptions. ↵

- Kay Rippelmeyer-Tippy, presentation during orientation workshop for participants in the 2018-19 Illinois tour of Crossroads: Change in Rural America, Edwardsville, IL, October 27, 2017. ↵

- Ann McCleary and Debra Reid, script of Crossroads: Change in Rural America (Washington, DC: Museum on Main Street program, Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, 2018). ↵

- McCleary and Reid, script of Crossroads. ↵

- McCleary and Reid, script of Crossroads. ↵

- McCleary and Reid, script of Crossroads. ↵

- McCleary and Reid, script of Crossroads. ↵

- McCleary and Reid, script of Crossroads. ↵

- McCleary and Reid, script of Crossroads ↵

- McCleary and Reid, script of Crossroads ↵

- McCleary and Reid, script of Crossroads ↵

- McCleary and Reid, script of Crossroads ↵

- McCleary and Reid, script of Crossroads ↵

- McCleary and Reid, script of Crossroads ↵