Chapter 11: Gathering around Sports, Entertainment, and Arts, Then and Now

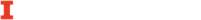

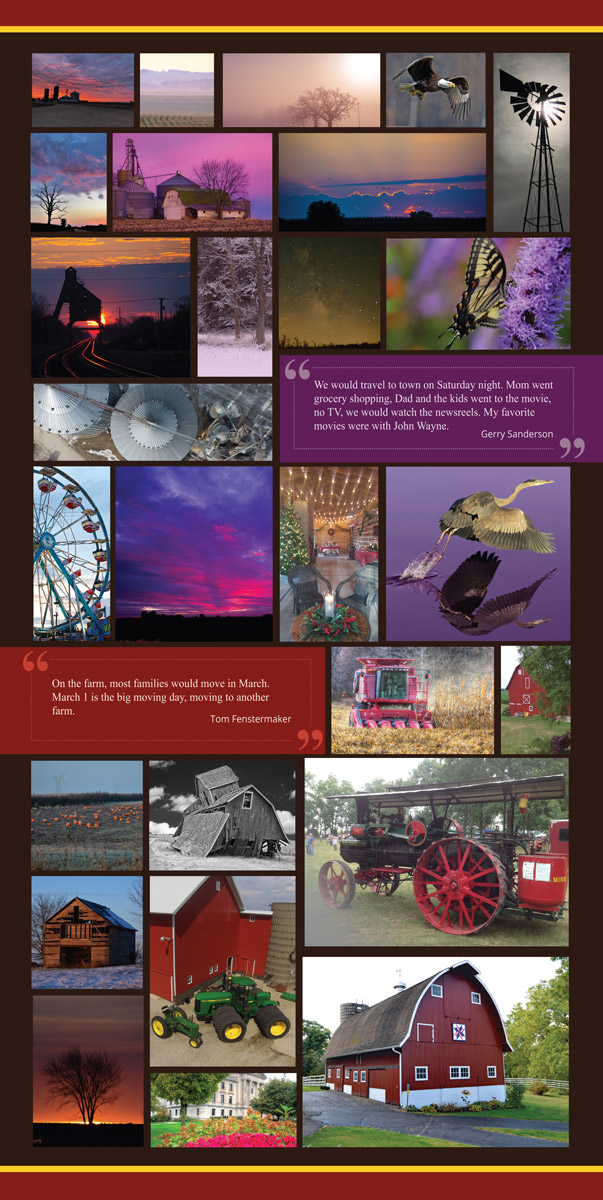

Expressive and recreational culture formed both the subject matter and the experiential content of companion exhibitions and programs presented by Illinois’s Crossroads: Change in Rural America host organizations, highlighting the cultural interconnectedness of the local, the statewide, and the national.

In conjunction with its “Classrooms & Community” exhibition, the Atlanta Museum presented a program entitled “Sports and Community.” It featured panelists who had been athletes and coaches at one-room schools, Atlanta High School, and Olympia High School. They discussed changes in the role of sports in school and community life, including the impact of Title IX and the development of competitive sports opportunities for girls. The event highlighted the Olympia High School girls’ softball team, which has been very successful and won several championships in recent years. It also included a screening of a video documenting the 1959 Atlanta High School basketball team’s victory in a sectional tournament. The program was well attended and enthusiastically received.[1]

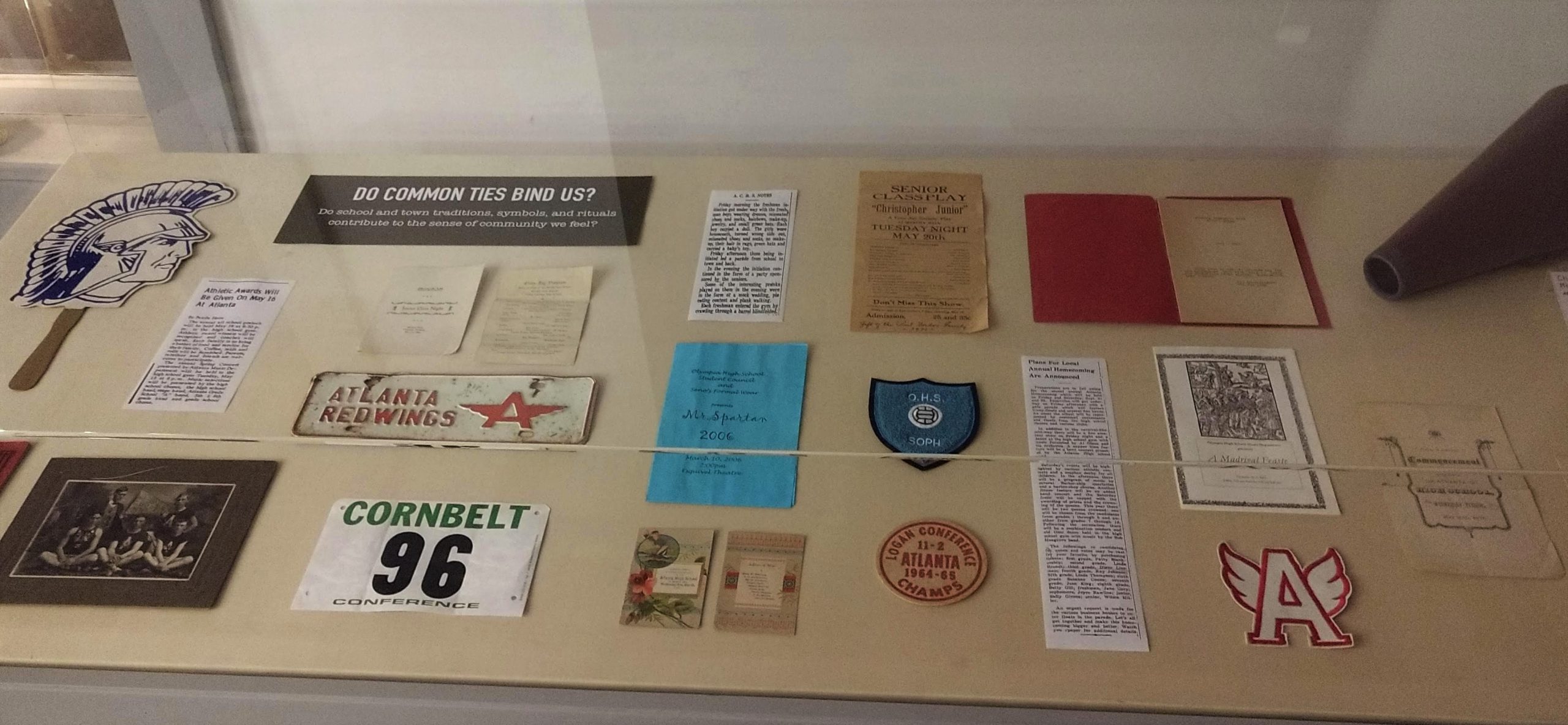

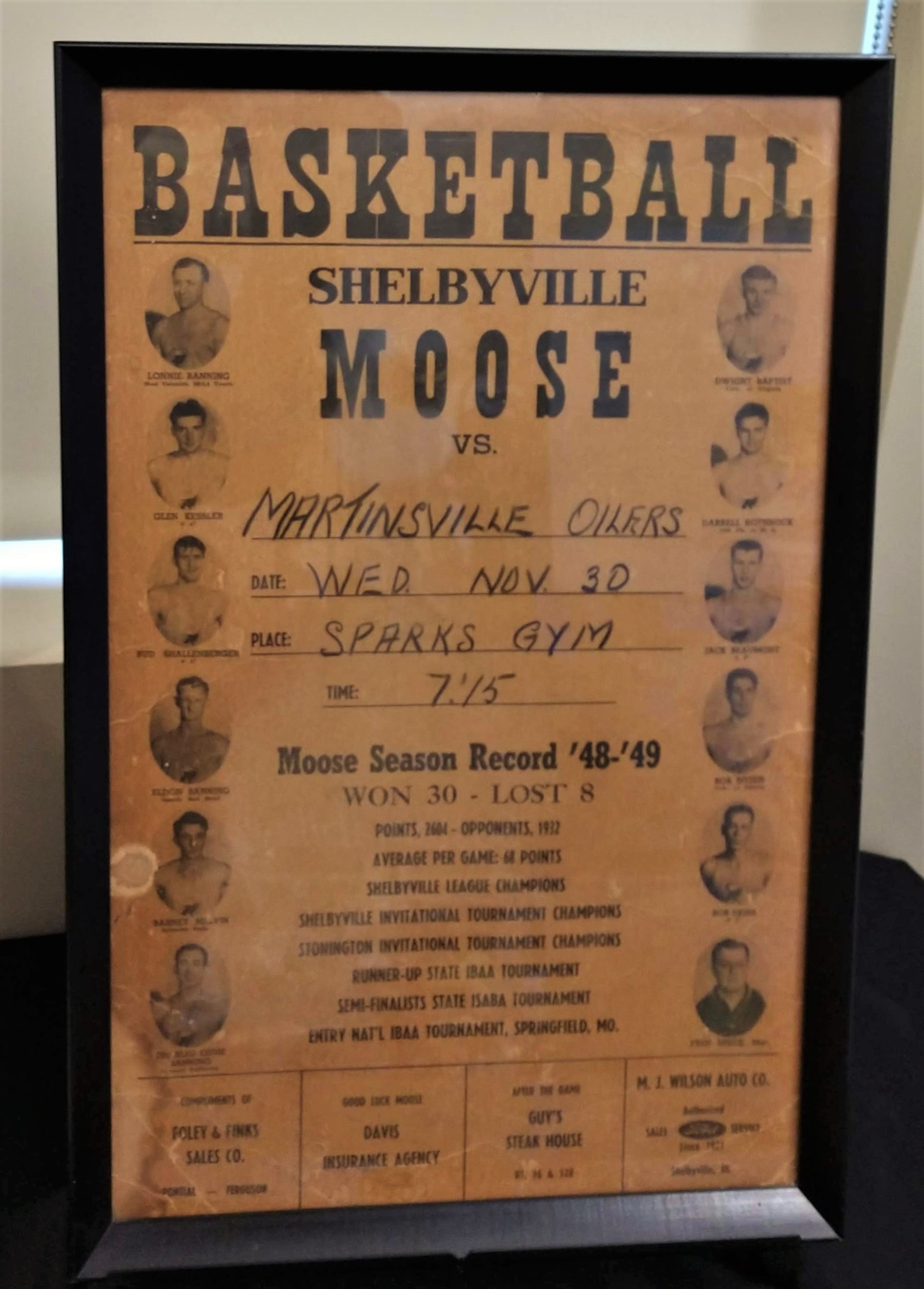

Similarly, the Lake Shelbyville Visitors Center’s companion exhibition featured a segment discussing the evolution of sports and other organized recreational and cultural activity in Shelby County. It featured a poster advertising a 1949 basketball game between the Shelbyville Moose and the Martinsville Oilers, as well as one from the Shelbyville Drive-In promoting movies released in 1956-57, including The Brave One, starring Michel Ray, and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt, starring Dana Andrews.[2]

As much as half a century before Ray and Andrews appeared on the Shelbyville Drive-In screen, dozens of renowned entertainers and speakers appeared–in person–on the stage of the Shelbyville Chautauqua Auditorium, to which another segment of the exhibition was devoted. They included national political figures William Howard Taft and William Jennings Bryan, temperance advocate Carry Nation, and evangelists Billy Sunday and Sam Jones, as well as performers such as the Jubilee Singers, the Goodman Band, the Davies Light Opera Singers, and the Shakespearian Players.[3]

Civic leaders commissioned local bridge builder H.B. Trout to construct the Chautauqua Auditorium in Shelbyville’s Forest Park in 1903 to serve as a venue for Chautauqua assemblies, festival-like gatherings consisting of a wide variety of educational and cultural presentations. Named for the Chautauqua Institution in New York, which pioneered the format, such assemblies were popular throughout rural America, including much of Illinois, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[4] (The Chautauqua movement of that period is not to be confused with present-day Chautauquas, which are similar in format but feature actors portraying historical figures.)

A twenty-sided polygonal (quasi-circular) wooden structure with a diameter of 150 feet, the Shelbyville Chautauqua Auditorium is architecturally distinctive and significant. It was patterned after the Rock River Assembly tabernacle (no longer in existence), which the initiators of the project had visited. Located in the northern Illinois community of Dixon, the tabernacle was designed by architect Morrison Vail.

The Shelbyville Chautauqua Auditorium’s unusual ceiling support system consists of radial trusses that converge in the center, eliminating any need for vertical pillars that might block the audience’s view of the stage. The apex of the proscenium is adorned by a neoclassical sculpture of three muse-like figures representing art, music, and drama, created by Robert Marshall Root, a regionally significant artist from Shelbyville who was also featured in the Visitors Center’s Crossroads companion exhibition.[5]

The Chautauqua Auditorium remained in use to varying degrees after the decline of the Chautauqua movement in the 1930s and ’40s, but it gradually fell into disrepair. As of late 2018 and early 2019, when Shelbyville hosted Crossroads, the auditorium faced an uncertain future. It was unclear whether either the city of Shelbyville, which owns the building, or the residents of the community, acting on their own behalf, would be able or willing to invest the hundreds of thousands of dollars necessary to restore the building to a safe condition rather than demolish it. An organization called Save Our Chautauqua raised funds and campaigned vigorously for the preservation of the auditorium.[6]

On March 17, 2020, Shelbyville residents voted “yes,” by a considerable margin, on a referendum asking whether the city should expend the funds necessary to maintain the building. Extensive restoration occurred during spring 2021.[7] During an appearance on the City Spotlight program produced by WEIU, a public television station based in Charleston, Mark Shanks, commissioner of public properties for the city of Shelbyville and a leader of the Save Our Chautauqua organization, said that he expected the auditorium to be ready to host events by summer 2021. (It has, in fact, begun hosting events.) He noted that in the months preceding the referendum, many residents emphasized that they want the building to be used frequently to make their investment in its preservation worthwhile, and he said that their request would be honored.[8]

A program presented by the Atlanta Museum featured an art form that was contemporaneous with the Chautauqua movement and reflected much the same spirit: mandolin ensemble music. Though it initially took hold in medium-sized and larger towns and cities throughout the United States, it subsequently influenced rural music making significantly.

The Orpheus Mandolin Orchestra, based in nearby Bloomington-Normal, performed at the Atlanta Museum on March 22, 2019. (The concert occurred shortly after the closing of Crossroads in Atlanta as a follow-up to the exhibition.) Though the ensemble plays recently composed repertoire in addition to older music, it closely resembles the mandolin orchestras that were prominent in college towns and small cities across the country a century or more prior and, in fact, is named after just such an ensemble that was active in Bloomington-Normal around that time.[9] During the concert, Matt Meacham of Illinois Humanities gave a presentation about the evolution of the mandolin within the United States, describing how it eventually became associated with rural America. (A member of the orchestra subsequently told Meacham that she often shares much of the same information with audiences during performances.)

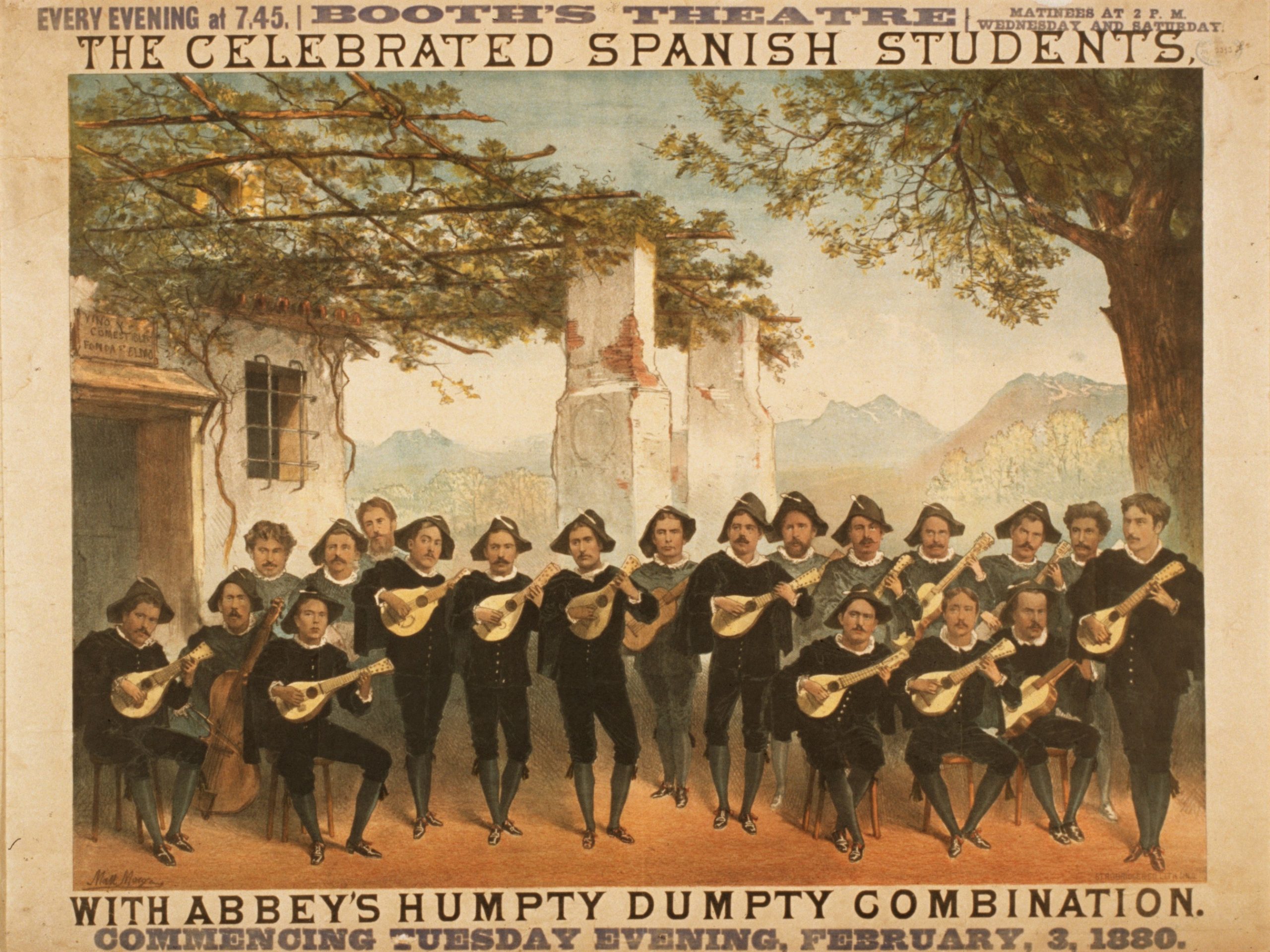

The mandolin was introduced to the United States by Italian and other European immigrants in the mid- to late nineteenth century, but its use was limited mostly to traditional music making within their cultural communities. In 1880, however, a Madrid-based string ensemble called the Spanish Students, specializing in formalized, stylized versions of music representing Spanish folk traditions, performed in Boston and New York to great acclaim. A newspaper article misidentified the bandurrias that several members of the group were playing as mandolins, sparking interest in the latter instrument among young people in the cities of the Northeast. Two groups bolstered the mandolin’s burgeoning popularity. One, an American group that was founded as an imitation of the Spanish Students but used actual mandolins rather than bandurrias, called itself, deceptively, the Original Spanish Students. The other, a band called the Boston Ideal, was somewhat similar in concept and consisted of highly proficient guitarists, banjoists, and mandolinists.[10]

A “mandolin craze” swept the nation over the next two decades as part of an amateur music-making trend among middle-class college students and townspeople. The vogue also encompassed brass bands, glee clubs, and barbershop quartets, and sheet-music arrangements of popular songs for piano or harmonium. Much like the Chautauqua movement, this variety of musical activity aimed to foster community fellowship, healthy recreation, and cultural enrichment. Mandolin ensembles’ repertoire, like those of many similarly oriented groups, typically included arrangements of light classical and operatic works, ballroom dances, marches, popular songs, and hymnody, as well as stylistically similar original compositions.

Responding to the demand, American musical-instrument manufacturers, including Chicago’s Lyon & Healy, began producing or increasing production of mandolins and other instruments in the mandolin family that were often used in mandolin orchestras, such as mandolas, mandocellos, and mandobasses. (The mandolin’s strings are tuned to the same pitches as those of a violin. Similarly, the mandola corresponds in its tuning to the viola, the mandocello to the violoncello, and the mandobass to the contrabass.)[11]

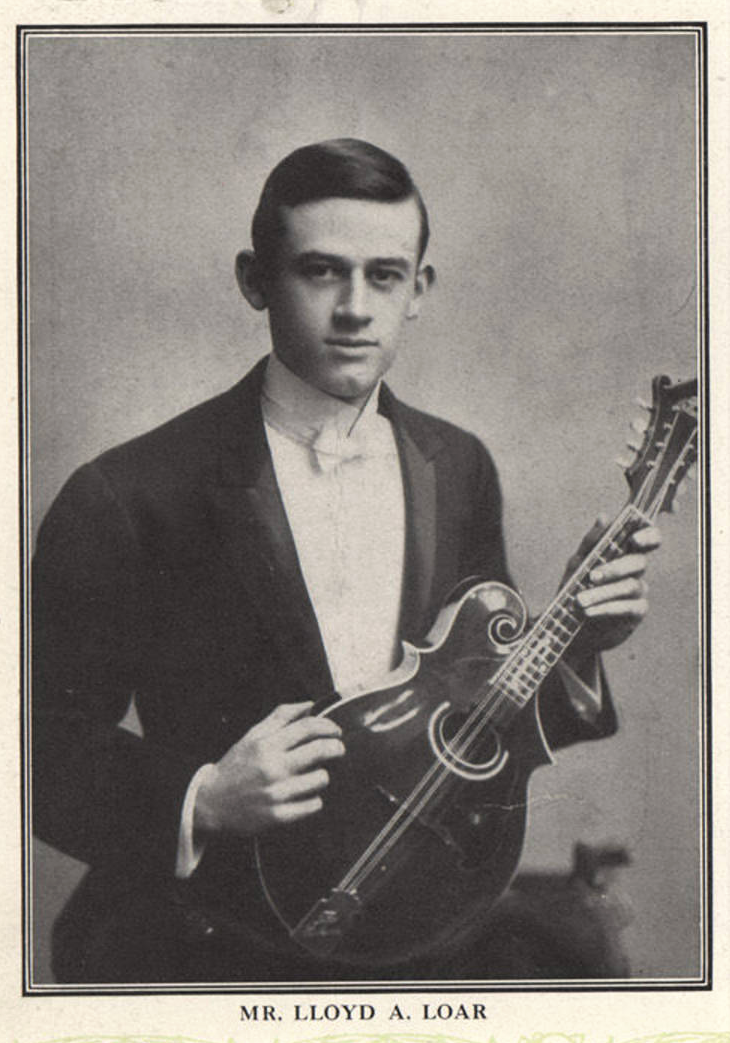

One such manufacturer was Gibson, then based in Kalamazoo, Michigan. An accomplished musician and engineer who worked for the Gibson company, Lloyd Loar, experimented with mandolin construction. His innovations resulted in mandolins that were louder and brighter in tone than most of their predecessors. The Gibson mandolin models designed by Loar became widely popular, influenced the work of other designers and manufacturers, and are still highly prized today. Loar was originally from the rural community of Cropsey in McLean County, Illinois, only about thirty miles northeast of Bloomington-Normal, and lived during his teenage years in Lewistown in western Illinois’s Fulton County (where renowned poet Edgar Lee Masters also lived and on which the setting of his Spoon River Anthology is partly based).[12] The Orpheus Mandolin Orchestra often pays tribute to Loar during its concerts and received an Illinois Humanities grant to prepare a presentation on Loar and his Illinois roots for a national conference of mandolin ensembles held in Bloomington-Normal in 2019.[13]

The “mandolin craze” waned in towns and cities in the 1920s, but mail-order catalogs introduced affordable mandolins to rural America, where their popularity grew and they were incorporated into existing vernacular musical traditions. Once mandolins became common in rural regions, people began building their own, patterning them after those sold through catalogs. In the 1930s and ‘40s, Bill Monroe, a mandolinist who was raised in rural west-central Kentucky and often played a Gibson mandolin incorporating Loar’s design innovations, made the instrument an essential component of his distinctive idiom of country string-band music, which came to be called “bluegrass.” The mandolin remains closely associated with that musical genre at present.[14]

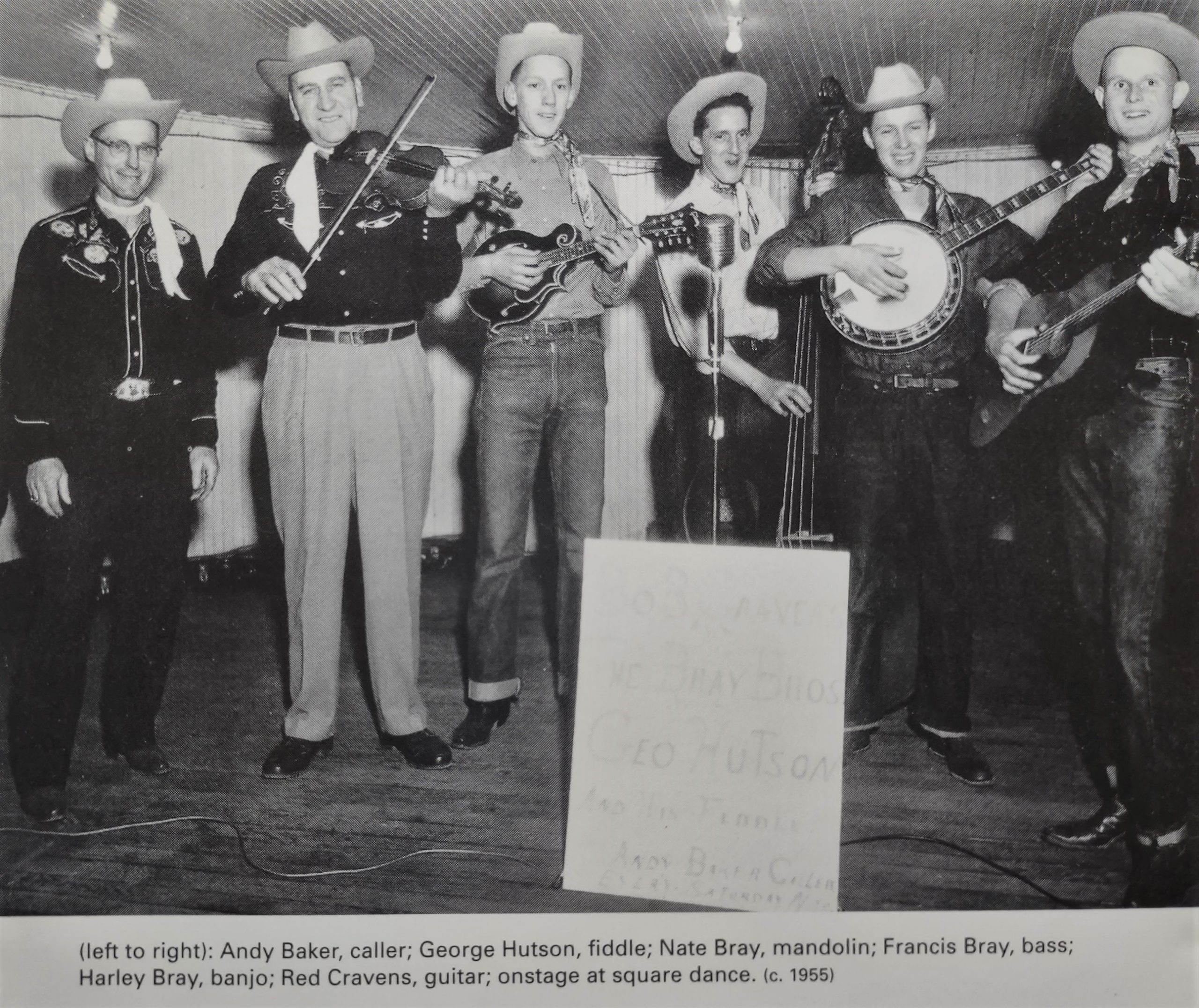

One bluegrass mandolinist whose technical fluency and creativity earned Monroe’s respect was Nate Bray, a member of a band known as either The Blue Grass Gentlemen or The Bray Brothers, depending on the context.

The group was based in Champaign-Urbana and performed regularly on the Cornbelt Country Style program on WHOW radio in Clinton, Illinois, during much of the 1960s. Recordings of the band’s music are available on the Liberty and Rounder labels.[15]

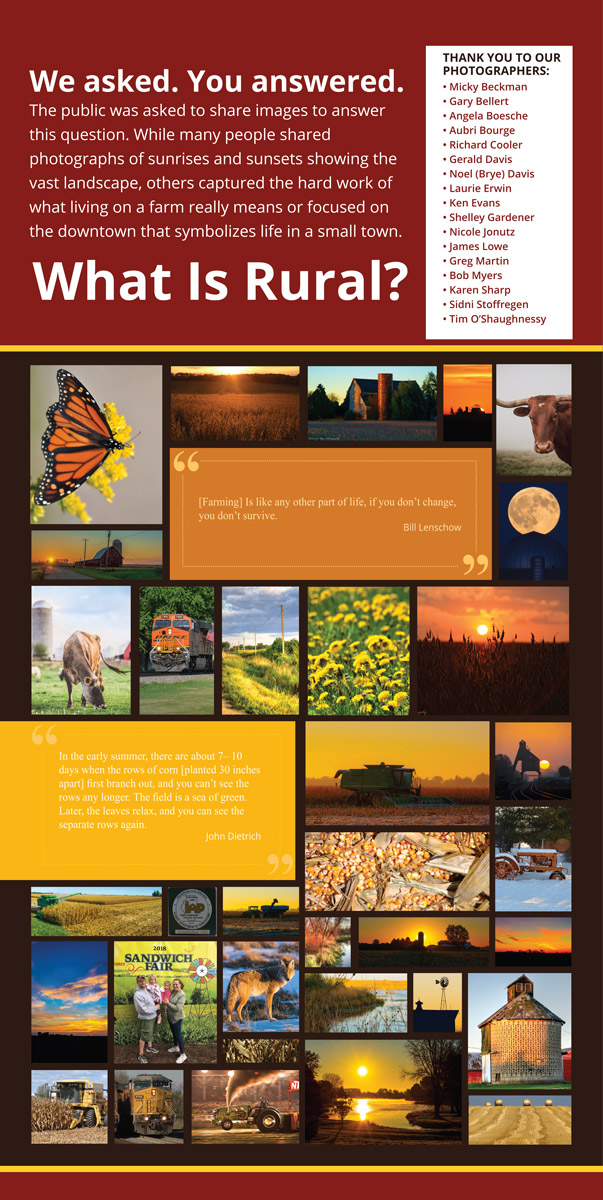

In addition to the Orpheus Mandolin Orchestra performance and the “Prairie Pathways” community mural project, the Atlanta Museum’s Crossroads-related artistic activities included an exhibition of paintings and photographs by local artists.[16] Similarly, the DeKalb County History Center held a photography contest and exhibition. The entries responded visually to the question, “What is rural?”[17]

Community-based cultural activity also figured significantly in the DeKalb County History Center’s companion exhibition. One segment was devoted to the many community festivals and gatherings that occur annually throughout the county, including the Cortland Summer Fest, the DeKalb Corn Fest, the Kirkland Fourth of July Celebration, the Waterman Lions Summerfest and Antique Tractor and Truck Show, the Pumpkin Fest in Sycamore, the DeKalb County Barn Tour, and the remarkable Sandwich Fair, which, since 1858, has showcased agricultural achievements and offered activities such as harness racing, baseball, truck and tractor pulls, antique car shows, carnival rides, and live music.[18]

The DeKalb County History Center and several of the other Crossroads host organizations presented a program by musician Chris Vallillo called The Farmer Is the Man: Songs from the Farm. Vallillo, a guitarist, singer, and songwriter who specializes in music that draws upon Midwestern folk traditions and reflects the region’s history and culture, lives in Macomb and has worked with Illinois Humanities in many capacities over the past three decades. Incorporating both music and contextual commentary, The Farmer Is the Man features traditional songs that speak of the challenges, rewards, tribulations, and triumphs of a life in agriculture, as well as original compositions such as “The Final Harvest,” based on the true story of a group of farmers in northern Illinois who cooperated to reap the crops planted by a fellow farmer who had since died in a tractor accident.[19]

Music also contributed to programming associated with Crossroads at the Lake Shelbyville Visitors Center, which hosted performances by several regional bluegrass and gospel groups.[20] The Old School Museum in Winchester also incorporated music into its activities. Winchester native Stuart Smith, a regionally prominent neo-traditional songwriter, singer, and guitarist, organized a concert featuring local musicians performing familiar selections from various traditions and genres with audience participation.[21] The closing weekend of Crossroads at the Old School Museum coincided with Christmas on the Square in Winchester, and a community choir sang carols as the last visitors perused the exhibition.[22]

- Catherine Maciariello, telephone interview with author, October 23, 2019. ↵

- Companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, Lake Shelbyville Visitors Center, Shelbyville, IL, December 15, 2018-January 26, 2019. ↵

- Brenda Elder, “The history of Forest Park and the early days of the Shelbyville Chautauqua, part 1 of 2,” posted on the “Around the County Past, Present and Future” Facebook page, March 3, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/Around-the-County-Past-Present-and-Future-109663313978838/. ↵

- Charles Joseph Pell Architects, Inc., “Shelbyville Chautauqua Auditorium,” 2015, https://www.cjparchitects.com/shelbyville-chautauqua-auditorium.html; Brenda Elder, “The history of Forest Park;” Shelbyville Daily Union staff, “Chautauqua Auditorium among Most Endangered Historic Places,” Effingham Daily News (Effingham, IL), April 26, 2018, https://www.effinghamdailynews.com/news/local_news/chautauqua-auditorium-among-most-endangered-historic-places/article_4b20b718-d261-5ba2-a2c5-7f82d89ad025.html. ↵

- Charles Joseph Pell Architects, Inc., “Shelbyville Chautauqua Auditorium,” Companion exhibition, Lake Shelbyville Visitors Center; Brenda Elder, “The history of Forest Park”; Shelbyville Daily Union staff, “Chautauqua Auditorium among Most Endangered Historic Places.” ↵

- Donnette Beckett, “Watch Now: How Shelbyville Saved its Iconic Chautauqua,” Herald & Review (Decatur, IL), October 22, 2021, updated November 6, 2021, https://herald-review.com/news/local/history/watch-now-how-shelbyville-saved-its-iconic-chautauqua/article_af9ec073-91eb-5465-b3e3-2efe5612eda0.html; Companion exhibition, Lake Shelbyville Visitors Center; Brenda Elder and Freddie Fry, telephone interview with author, October 1, 2019. ↵

- Donnette Beckett, “Watch Now: How Shelbyville Saved its Iconic Chautauqua,”; Herald & Review staff, “Shelbyville Chautauqua Renovation Plan Gets Support,” Herald & Review (Decatur, IL), March 18, 2020, https://herald-review.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/shelbyville-chautauqua-renovation-plan-gets-support/article_82bac0a9-aae1-5ac1-9bd6-648de262dd24.html. ↵

- City Spotlight, “Shelbyville,” WEIU TV (Charleston, IL), PBS, March 10, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/video/shelbyville-ybpk3p/. ↵

- “About Orpheus Mandolin Orchestra,” Orpheus Mandolin Orchestra Facebook page, accessed April 1, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100057324105355&sk=about_details. ↵

- Walter Carter, The Mandolin in America: The Full Story from Orchestras to Bluegrass to the Modern Revival (Lanham, MD: Backbeat Books, 2016), 8-44; Lindsay Conway, “From Baroque to Bluegrass, a Globe-Trotting Instrument,” NLS Music Notes, Library of Congress, August 20, 2020, https://blogs.loc.gov/nls-music-notes/2020/08/from-baroque-to-bluegrass-a-globe-trotting-instrument/; Kara Kundert, “50 States of Folk: The Mandolin’s Ellis Island Journey to the All-American Sound,” No Depression: The Journal of Roots Music, January 15, 2020, https://www.nodepression.com/50-states-of-folk-the-mandolins-ellis-island-journey-to-the-all-american-sound/; Paul Ruppa, “Mandolin,” Grove Music Online (online edition of The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians), 2013, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2250132. ↵

- Carter, The Mandolin in America, 8-44; Conway, “From Baroque to Bluegrass”; Kundert, “50 States of Folk”; Ruppa, “Mandolin.” ↵

- Kundert, “50 States of Folk”; Roger Siminoff, “Lloyd Allayre Loar,” Siminoff Banjo and Mandolin, accessed April 1, 2023, https://www.siminoff.net/lloyd-loar; James Stanlaw, “The Central Illinois Roots of Lloyd Loar and the Growth and Development of the Mandolin Orchestra Tradition in America,” Illinois State Museum, Springfield, February 5, 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20200929073713/http://www.illinoisstatemuseum.org/content/central-illinois-roots-lloyd-loar-and-growth-and-development-mandolin-orchestra-tradition. In “Lloyd Loar: An Alternative View,” George Gruhn and Joe Spann propose that Lloyd Loar’s contributions to the Gibson company’s design innovations might not have been as substantial as is generally believed. They present evidence suggesting that the Gibson company might have exaggerated Loar’s role for marketing purposes. George Gruhn and Joe Spann, “Lloyd Loar: An Alternative View,” Vintage Guitar Magazine, January 2018, https://www.vintageguitar.com/33029/lloyd-loar/. ↵

- Melcher + Tucker Consultants, “Arts in the Cemetery, Midwest Women Artists Conference, Mexico-Chicago Literature Festival and Podcasts by Men of Color Among Statewide Projects Selected for Illinois Humanities Funding,” Illinois Humanities, September 5, 2019, https://www.ilhumanities.org/news/2019/09/arts-in-the-cemetery-midwest-women-artists-conference-mexico-chicago-literature-festival-and-podcasts-by-men-of-color-among-statewide-projects-selected-for-illinois-humanities-funding/. ↵

- Carter, The Mandolin in America, 81-100; Conway, “From Baroque to Bluegrass”; Kundert, “50 States of Folk”; Ruppa, “Mandolin.” ↵

- Matt Fink, “Biography: Bray Brothers,” AllMusic, accessed April 1, 2023, https://www.allmusic.com/artist/bray-brothers-mn0001201809/biography; John Hartford, liner notes in 419 W. Main by the Bray Brothers, Rounder Records 0015 (1972) and CD 0015 (1997); “Red Cravens & The Bray Brothers–419 West Main,” No Depression: The Journal of Roots Music, May 1, 1998, https://www.nodepression.com/album-reviews/red-cravens-the-bray-brothers-419-west-main/. ↵

- Exhibition of work by local artists accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, Atlanta Museum, Atlanta, IL, February 2-March 16, 2019. ↵

- “What Is Rural?,” segment of “Identity,” section of a companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, DeKalb County History Center, Sycamore, IL, May 11-June 22, 2019, content from which is available at https://dchcexhibits.org/crossroads/identity/. ↵

- “Persistence,” section of a companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, DeKalb County History Center, Sycamore, IL, May 11-June 22, 2019, content from which is available at https://dchcexhibits.org/crossroads/persistence/. ↵

- “Chris Vallillo Performs: ‘Farmer is the Man, Songs from the Farm’,” DeKalb County History Center, May 19, 2019, https://www.dekalbcountyhistory.org/events/chris-vallillo-performs-farmer-is-the-man-songs-from-the-farm/; Chris Vallillo, various informal conversations with author and performances attended by author, 2018 and following. ↵

- Brenda Elder and Freddie Fry, telephone interview with author, October 1, 2019. ↵

- Tricia Wallace, telephone interview with author, October 15, 2019. ↵

- Matt Meacham, visit to the Old School Museum, Winchester, IL, December 8, 2018. ↵