Chapter 16: Conclusion—Blessings, Curses, or Both?

Crossroads: Change in Rural America prompted critical reflection on rural Illinois’s past, present, and future.

The Atlanta Museum’s capacity to realize its worthy aspirations has benefited in recent years from a dramatic increase in visits to Atlanta by individuals and tour groups enamored of Route 66 and the lore surrounding it.

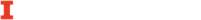

Similarly, Mississippi riverboat tourism has made a significant impact on Chester lately. Increasingly, excursion boats dock there, and passengers visit restaurants, businesses, sites, and institutions in the community.

Consequently, river travel once again contributes significantly to local economic and cultural activity, much as it did a century or two ago. “That was our main source of transportation early on for goods, and now we’ve sort of come full circle and have people from all over the world stopping in Chester as a result of riverboat transportation and tourism,” noted Chester Public Library volunteer Brenda Owen.[1]

Many such tourists visited Chester Public Library while Crossroads: Change in Rural America was there. If they viewed the library’s original documentary film about three local farming families, they saw a striking image involving river transportation of a different kind: a ferry hauling a gargantuan, technologically sophisticated agricultural implement from the eastern bank of the Mississippi River to Kaskaskia Island.

“The Vasquezes, with their huge technology and so forth, now farm a portion of Kaskaskia, so you have these modern farming techniques being used in our first state capital, which is all basically a rural farming area now,” noted Tammy Grah, administrative librarian. “We had an image of a thousands-of-dollars piece of equipment crossing the river on this very small ferry, but that’s the easiest way for them to get there.”[2]

That scene seems to encapsulate much of what the companion exhibitions and programs produced by Crossroads host organizations indicate about continuity and change in rural Illinois over the state’s two-hundred-year history. Kaskaskia remains a center of agricultural productivity, thanks to the same fertile soil and Mississippi River access that made it the breadbasket of French Colonial America three centuries ago. That agricultural productivity and the commerce that it generated drew thousands of people to that place—some not of their own choosing—and enabled it to become the gateway to a promising new state.

Today, however, Kaskaskia lies in the midst of the Mississippi, nearer its western bank, inhabited by an infinitesimal fraction of the number of people who called it home when Illinois was young, and most state-level governmental decisions now are made in cities 150 to 350 miles away. Furthermore, the agricultural production is executed by mechanical behemoths that surely would have startled even the most imaginative residents of Kaskaskia circa 1818.

How would the signatories of the state’s first constitution and other people involved in the pursuit of statehood status for Illinois—of whom David Joens, director of the Illinois State Archives, spoke during a presentation at Chester Public Library on September 23, 2018—evaluate the evolution of rural Illinois since their own era if they were to visit ours?

How would those architects of Illinois’s statehood respond to the innovations in agricultural technology and the changes in farming practices to which Illinoisans have both contributed and adapted? How would they interpret the impacts of internal combustion engines and of electricity, telecommunications, and the Internet, as well as the generation of energy from both fossil fuels and renewable resources and its many environmental, economic, and social ramifications?

What would they have to say about the manifold ethnic and immigrant communities that now reside in rural Illinois, the reasons why they arrived here, the systemic discrimination that many of them have endured, and the flawed, yet significant, progress that has been made toward overcoming it? The labyrinthine networks of railroads and roads that traverse the state, having long since supplanted the river routes so familiar to them, as well as renewed interest in river travel for purposes of both tourism and environmentally friendly transportation of goods? Advances in medicine and access to health care? The development of educational institutions and of their roles within their communities? Changing relationships between small towns and the unincorporated areas surrounding them? The ongoing evolution of the athletic and artistic pursuits around which communities gather?

Would they view those developments as blessings? As indications that the legendary Curse of Kaskaskia was all too real and remains in effect? A combination of both?

Although Rural Worlds Lost: The American South, 1920-1960 by Jack Temple Kirby (Louisiana State University Press, 1987) examines another (albeit adjacent) geographic region and a different (though partly concurrent) period of time, one could replace “New South” with “rural Illinois” in its concluding sentence with little or no reduction in veracity: “A new New South had appeared, but whether it was better than the old one was a question not easily and fairly answered.”[3]

If the founders of our state could project themselves forward two centuries, perhaps they, along with more than a few present-day rural Illinoisans, would concur with this passage from The Transformation of Rural Life: Southern Illinois, 1890-1990 by Jane Adams (University of North Carolina Press, 1994): “Farm families and people who have grown up in rural areas seem caught on the horns of a dilemma: The old way was materially impoverished but far richer socially than the present. Must one quality be lost in order to have the other?”[4]

The six Illinois organizations that hosted Crossroads: Change in Rural America in 2018-19 are doing their best to make the answer to that question “no.” To a heartening extent, they are succeeding even as they face daunting challenges. They and others like them demonstrate remarkable dedication to the ongoing cultural vitality of their communities, and they act upon that dedication with equally remarkable ingenuity, industriousness, and perseverance. If current and future generations of rural Illinoisans learn from their examples and apply what they learn, then perhaps there is at least a chance that the social fabric of our state will remain intact or even grow sturdier amid whatever changes the next two centuries bring.

- Tammy Grah, Brenda Owen, and Carolyn Schwent, telephone interview with author, October 22, 2019. ↵

- Tammy Grah, Brenda Owen, and Carolyn Schwent, telephone interview with author, October 22, 2019. ↵

- Jack Temple Kirby, Rural Worlds Lost: The American South, 1920-1960 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987), 360. ↵

- Jane Adams, The Transformation of Rural Life: Southern Illinois, 1890-1990 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), xviii. ↵