Chapter 10: Classrooms, Community, and Change

The evolutionary trajectories of schools in rural Illinois and those of the people and places that they serve intertwine and influence one another. Furthermore, those trajectories manifest and contribute to salient trends in the evolution of rural Illinois. One Crossroads: Change in Rural America host organization produced a substantial companion exhibition examining these interrelationships from its own local vantage point.

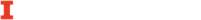

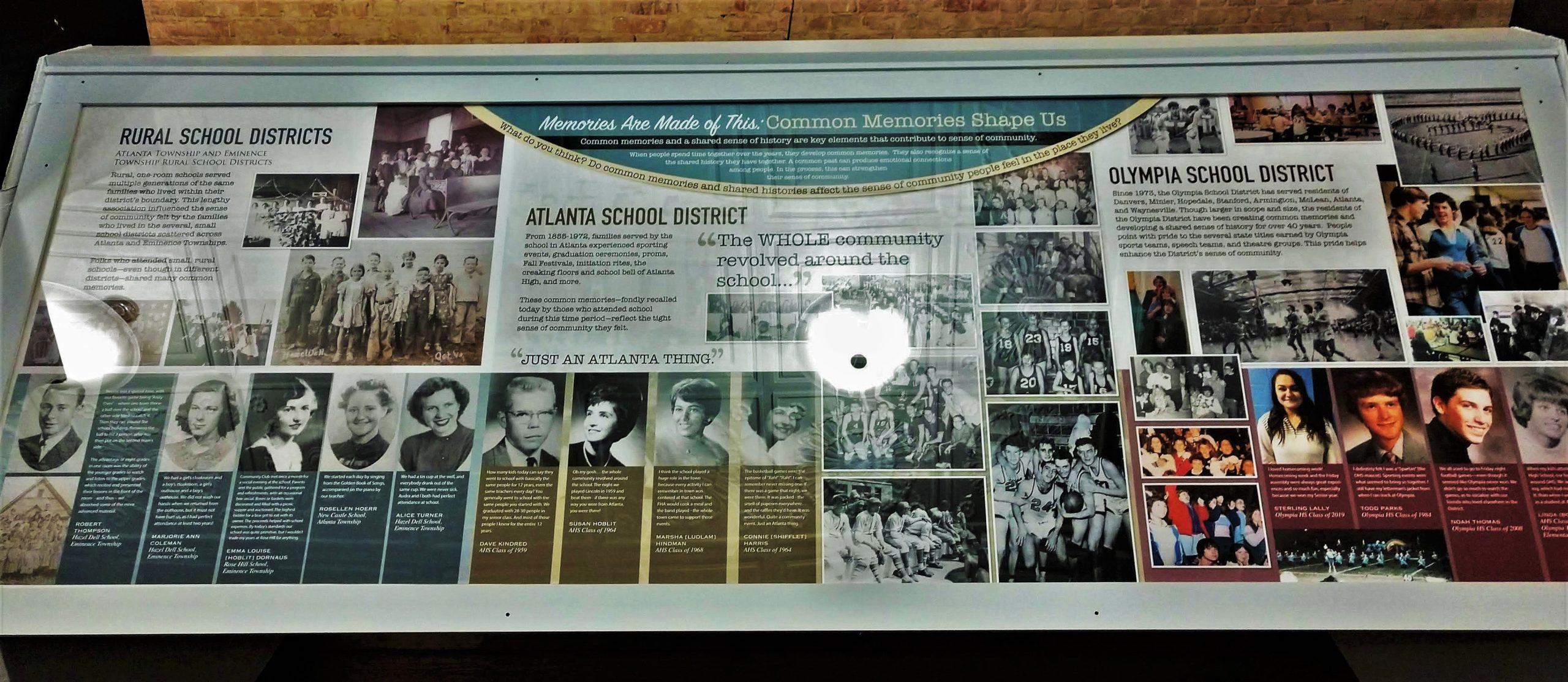

Yet another major factor in the social evolution of many rural Illinois communities has been school consolidation, a trend examined in an ambitious Crossroads companion exhibition produced by the Atlanta Museum. Incorporating the findings of extensive archival and oral-history research, “Classrooms & Community” chronicled the incremental merger of rural schools in northeastern Logan County since the 1940s and its multifaceted impact on local social dynamics and community identity. Bill Thomas, a former teacher and school administrator who serves as the treasurer of the Atlanta Public Library District, which encompasses the museum, curated the companion exhibition with substantial input from Museum Director Rachel Neisler, Library Director Catherine Maciariello, and others. The exhibition invited viewers to assess whether its content substantiated its thesis statement: “A school’s location and the size of the geographic area it serves impact the degree to which it contributes to that area’s sense of community.”[1]

In the mid-nineteenth century, five rural school districts were established within Atlanta Township, and eight were founded within the adjacent Eminence Township. Each had a one-room school. The schools were distributed so that no student had to walk more than two miles to attend. In the late 1940s, as part of a statewide school consolidation trend, those thirteen rural districts merged into the Atlanta School District, and the one-room schools closed. From approximately 1948 until 1972, students from throughout the Atlanta and Eminence townships rode buses to school in Atlanta.

In a second phase of consolidation, the Atlanta School District was absorbed into the newly established 377-square-mile Olympia School District in 1972. The exhibition text explained, “The Olympia district stretches from Atlanta in the south to Danvers in the north, and from Waynesville in the east to Hopedale in the west, making it the second largest geographic school district in Illinois. When the Olympia district was established, each of the eight communities comprising it had its own elementary school. The Olympia district now includes three grade-school attendance centers—in Atlanta, Danvers, and Minier—along with Olympia Middle and High schools located outside Stanford.”

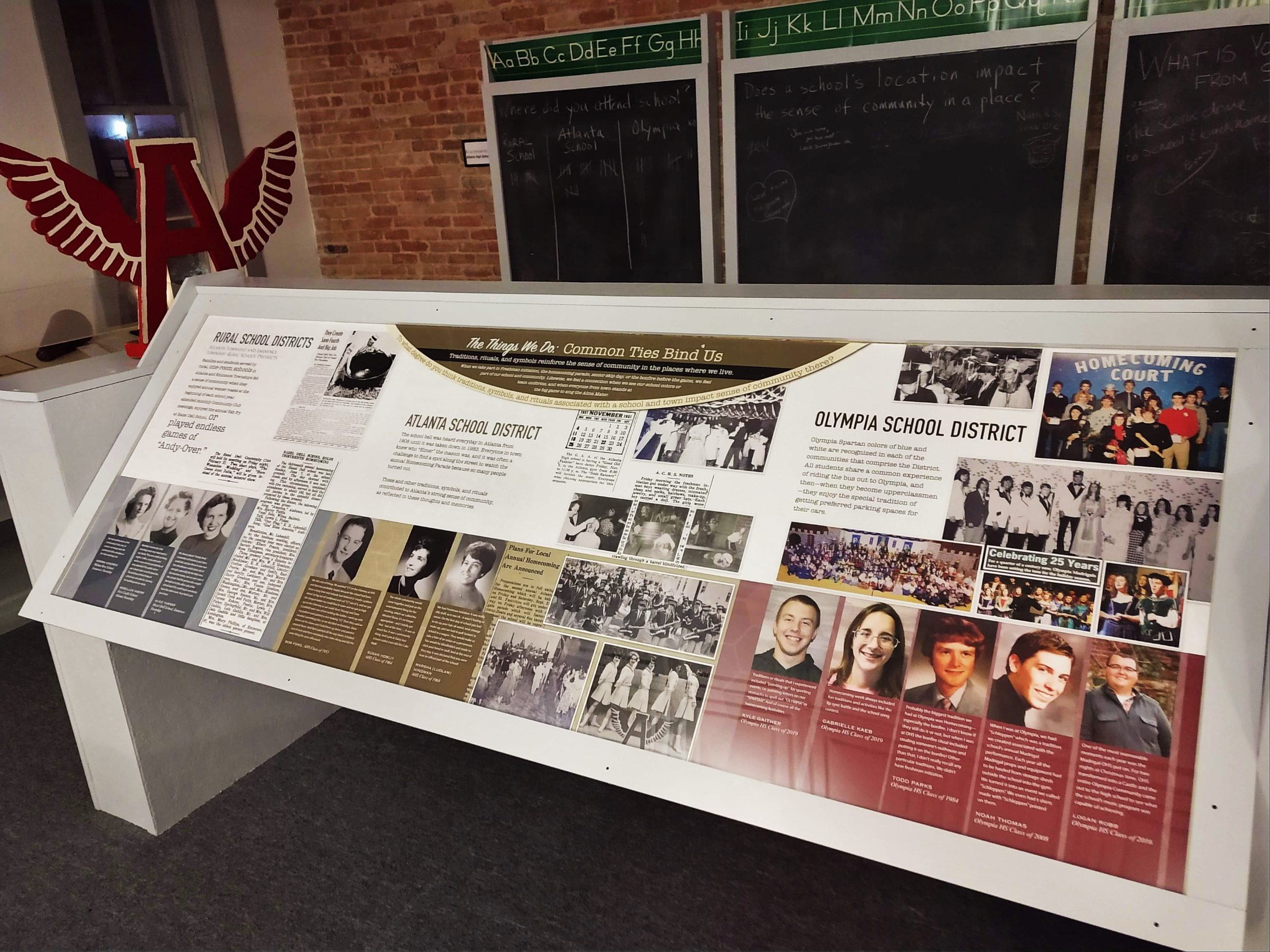

“Classrooms & Community” included four main sections, each of which was introduced by one or more framing questions:

“Places in the Heart—Common Places Define Us”

- Do you think the location and size of the rural school districts around Atlanta and that of the Atlanta CUSD [Community Unit School District] #16 influenced the sense of community felt by the families and students who lived in these places when those districts existed?

- What about the Olympia School District? Does that district’s location and size affect the sense of community felt by the people it serves?

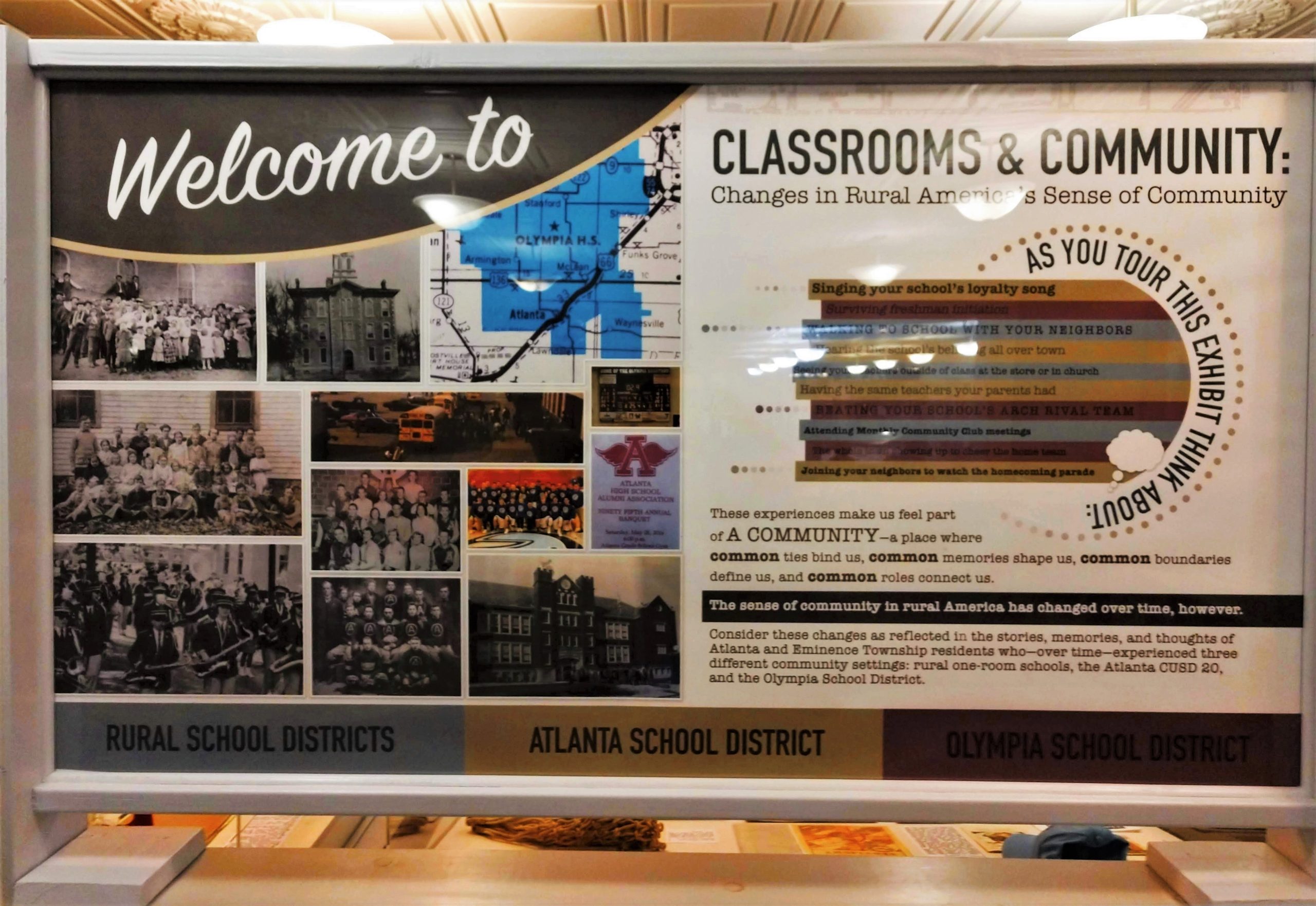

“Memories Are Made of This—Common Memories Shape Us”

- What do you think? Do common memories and shared histories affect the sense of community people feel in the place they live?

“The Things We Do—Common Ties Bind Us”

- To what degree do you think traditions, symbols, and rituals associated with a school and town impact the sense of community there?

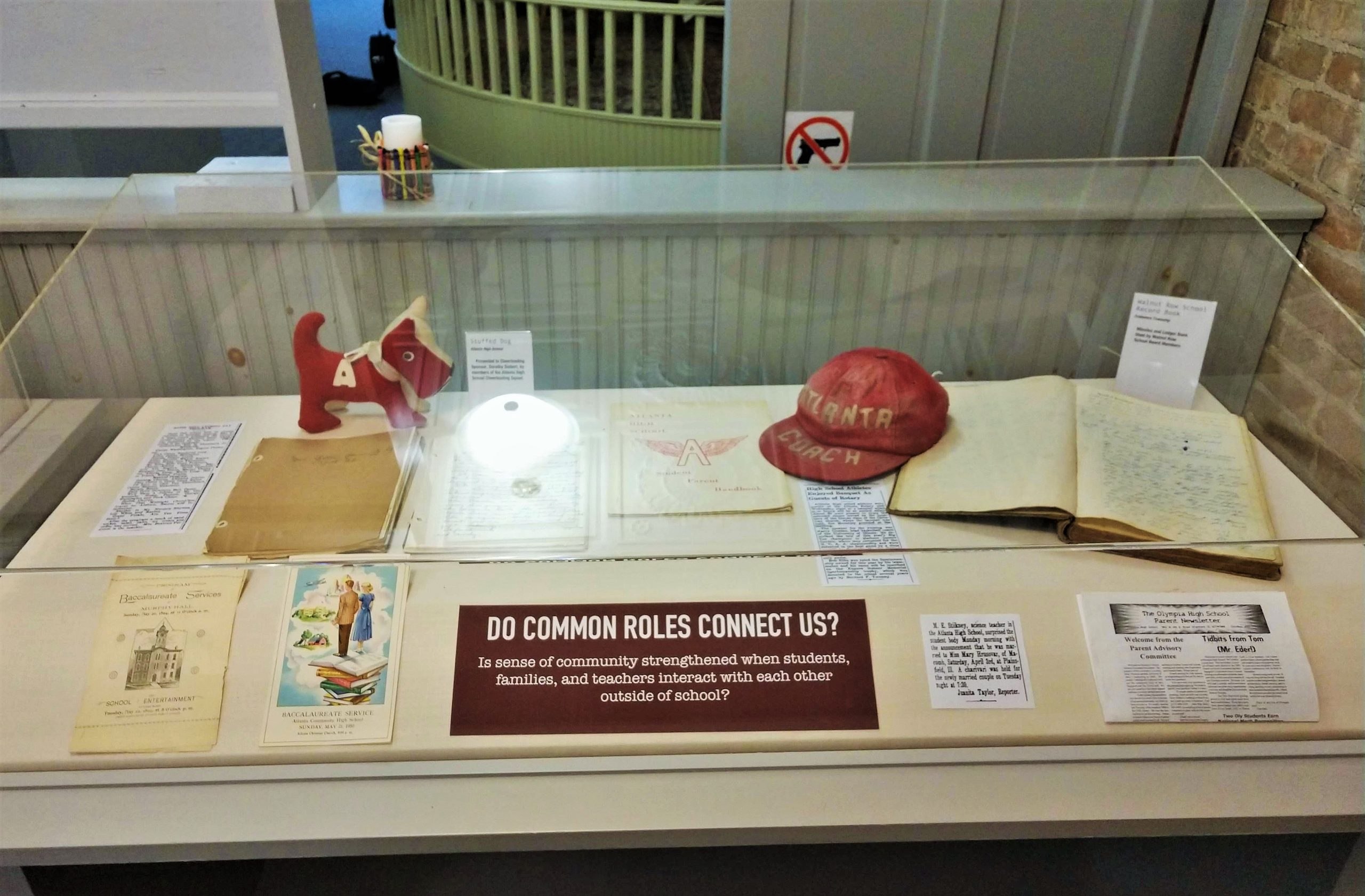

“Where Everybody Knows Your Name—Common Roles Connect Us”

- How much do you think sense of community is strengthened when students, families, and teachers interact with each other outside of school?[2]

The exhibition incorporated quotations from interviews with alumni, students, and teachers from the featured schools. Their comments accentuated the significance of schools as a community nexus and expressed various opinions as to whether consolidation had strengthened or weakened the bonds of fellowship.

Alumni of one-room country schools emphasized the camaraderie that resulted from sharing experiences among a small group of peers over an extended period. “All the little rural school communities were close-knit,” commented one who attended Eminence and Hazel Dell schools. “You felt you belonged to your school.” A graduate of Bloomingdale School recalled, “I was the only first grader in my class. There were ten to twelve kids in the whole school.” The trek to and from school held significance for many of them: “I remember walking to [Pleasant Hill] school through Grandpa Henry Quisenberry’s timber, then across a field or pasture to the Union road, and then on to school, after going through a barbed-wire fence,” said one.

Several shared observations about classroom and breaktime activities that fostered fellowship. According to a Hazel Dell graduate, “The advantage of eight grades in one room was the ability of the younger grades to watch and listen to the upper grades, which recited and presented their lessons in the front of the room, and thus we absorbed some of the more advanced material.” Students at New Castle School “started each day by singing from the Golden Book of Songs, accompanied on the piano by our teacher.” At Hazel Dell, “We had a tin cup at the well, and everybody drank out of the same cup. We were never sick.” “Recess was a special time, with our favorite game being ‘Andy Over,’ where one team threw a ball over the school and the other side tried to catch it. Then they ran around the school building, throwing the ball to hit a person, who was then put on the second team’s side,” explained another Hazel Dell alumnus.

One-room schools elicited a spirit of community not only among the students but also among their families and neighbors. One person commented, “On Christmas Eve, all the country schools brought their program to the Eminence church. That was a big program, followed by Mr. and Mrs. Santa Claus, who handed out sacks of candy, an orange, and nuts to all the kids.”

Several alumni of country schools fondly recalled the monthly Community Club gatherings that took place there. “I remember them being joyous occasions. It was an opportunity for adults in the area to socialize with one another and for the teacher to meet the parents of the students,” a Clear Creek School graduate explained. A proud alumna of Rose Hill School remembered, “Parents and the public gathered for a program and refreshments, with an occasional box social. Boxes or baskets were decorated and filled with a picnic supper and auctioned. The highest bidder for a box got to eat with its owner. The proceeds helped with school expenses.” Students at Walnut Row School “had spelling bees at the Community Clubs and, of course, we always won. We performed skits and plays at the club meetings, too.”[3]

People who attended school in Atlanta between the first and second phases of consolidation also described the school as a central point around which local residents coalesced. The symbiosis between the school and the community seems to have differed somewhat in character from the symbioses between the one-room schools and their districts, however.

One Atlanta High School graduate remarked, “Every activity I can remember in town was centered at that school. The FHA [Future Homemakers of America] would cook a meal, and the band played. The whole town came to support those events.” Another remembered, “The basketball games were the epitome of ‘Rah!’ ‘Rah!’,” adding, “It was packed—the smell of popcorn everywhere—and the raffles they’d have. It was wonderful. Quite a community event.”

One means of generating camaraderie was “freshman initiation. It was really silly stuff, so it was okay—it wasn’t hazing or mean. On the first day of school, you had to do up your hair all weird, wear strange makeup, and we had to pull seniors to school in a wagon. They would make us take a bite of an onion or a persimmon,” an AHS alumnus recalled. “At the end of the day, it was declared that you were now an official part of the school!”

Another link between AHS and the community was the school’s faculty and staff. “There’s this thing about our school and the people who worked there: Most of them lived in town,” one graduate observed. “It was a family atmosphere. Mrs. Pryor lived her whole life here. Mrs. Oldaker went to the same church and lived right down the road from my grandparents.” Another said, “In terms of teachers, we had Phil McCollough for social studies and Dorothy Colaw for math. They taught both my father and me.” He continued, “When you were still in school, it was ‘Mrs. Colaw,’ but when you graduated, she became ‘Dorothy,’ because she lived just a block down from my dad’s shop.”[4]

Comments from Olympia High School (OHS) students and faculty suggest that while there is notable camaraderie within the school, the school is less able to foster a sense of community throughout the geographic area that it serves than its predecessors were. One OHS student remarked, “Overall, I love going to Olympia, because I think it is the perfect size. You get to know most of the people in the school fairly well, and it’s just big enough to blend in if you want to, but just small enough to stand out if you try to. However, with a district that is composed of so many towns, spread out so far apart, it makes trying to hang out with your friends outside of school really inconvenient.” Similarly, an OHS graduate said, “It was fun to meet all these other kids from towns across the district. I felt part of an Olympia group, but I only knew those other kids for the four years I was in high school. The friendships I still have from my high-school days are [with] kids who were from Atlanta, where I grew up.”

Extracurricular activities provide opportunities for connection among Olympia students and between students and other area residents. “One of the most memorable moments each year was the madrigal [concert] OHS put on. For two nights at Christmas time, OHS transformed into a castle, and the entire Olympia community came out to the high school to see what the school’s music program was capable of achieving,” a graduate noted. “We all used to go to Friday night football games,” another remarked. “We didn’t go so much to watch the games as to socialize with our friends who lived elsewhere in the district.” Another alumnus recalled, “Homecoming week always included fun traditions and activities like the lip-sync battle and the school-song contest.” Some of those traditions might have been more fun for some than for others: “When I was at OHS the [homecoming] bonfire ritual included stealing someone’s outhouse and putting it on the bonfire!”

On the other hand, OHS students and faculty seem not to have a sense of belonging to a broader community in which they are mutually invested to the same extent that AHS and one-room school alumni and their teachers did. “I personally never saw my teachers much outside of school. That’s because there weren’t really any teachers that lived in my hometown of McLean. If I did see any of my teachers out and about, though, I always made sure to say hello! It was kind of a novelty to see teachers in the wild in a setting outside of school!” said one recent graduate. A teacher commented, “Except for extracurricular activities, I don’t see students often, as I live outside the district in Normal. Sometimes I run into a student at his or her job. But overall, those interactions are few and far between.”

The consensus among one-room school and Atlanta school alumni seemed to be that the second phase of consolidation precipitated a substantial decline in community cohesion. One remarked, “When school things went on here in Atlanta, most people, like my parents, attended. Like plays—my parents came, ‘cause they always knew somebody in the show. When things are out at Olympia, it’s ‘out of sight—out of mind.’ We don’t know anybody in the activities, so why bother to go?” Another observed, “We had in our high school [Atlanta] probably 150 students, at most, at one time, so you knew everybody in school. You’d see all the same teachers for years. Now, the school is out in the wilderness. I’m sure there’s an economic benefit to it, but I can guarantee you, nobody is going to feel romantic about Olympia High School.”

“Nearly fifty years after Olympia was established, it has taken its toll on this community. I really don’t think there are any Olympia communities that are thriving,” commented another AHS graduate. “All these little communities we combined into this big school district. I think it’s caused the smaller towns to die out because of the consolidation.”[5]

That last observation raises a question with potentially far-reaching significance: If it is true that those small communities have declined, did the decline occur because they lost their local schools, or are both the loss of local schools and the decline of small communities attributable to broader socioeconomic trends? The “Classrooms & Community” exhibition implicitly invited viewers to ponder that question for themselves.

It also presented contrasting perspectives from people with first-hand experience of Olympia High School. An OHS graduate explained, “My ‘community’ was bigger than my hometown of Atlanta. The geography of Olympia sort of forced me to explore other towns. We felt sort of bound to each other because we all went to school out in the middle of a cornfield.” A teacher recalled, “When the Olympia consolidation happened, I’d have to say that students from McLean, Waynesville, and Atlanta didn’t really like each other as their schools had always been rivals. But when they all went out to Olympia Middle School together, they ended up becoming best friends.” Another remarked, “Olympia creates challenges in terms of the feeling of community after the school day ends–thanks to the large size of the district. I think it takes more effort on the part of those involved to make sure that sense of community remains. It’s easy to not be involved, but I think that would mean losing touch with the greater picture.”[6]

In addition to the oral-history content, “Classrooms & Community” featured many artifacts and visual components, including a video incorporating maps and illustrations showing how school mergers occurred, created by a media production graduate student at Illinois State University in Normal.[7] The exhibition earned an award from the Illinois Association of Museums in 2019.[8]

Catherine Maciariello, an AHS graduate who returned to Atlanta after working in arts administration and philanthropy in several cities, said that she and others involved in the Atlanta Museum’s hosting of Crossroads: Change in Rural America learned a great deal from developing their companion exhibition and hearing viewers’ responses to it: “In the early days of the rural schools, community was really defined as the people who lived within about a two-mile radius of the school, and there were very strong bonds that were manifested through activities that took place at those schools. . . . As those more isolated districts were drawn together in the larger high school that was located in Atlanta itself, there were relationships that had to be redefined, and people talked a lot during that period about the differentiation between ‘townies’ and the people who came from the country, and it took a period of time for those two kinds of cultures and populations to merge and to become one, but that happened. . . . The identity of the centralized school became, really, the driving animator of local culture in town.”[9]

Maciariello continued, “As, then, that school went away and the larger consolidated district which encompasses eight towns happened, there was pretty radical redefinition of what community meant in its relationship to education. And what we discovered—which, I think, we didn’t understand so much at the beginning—was that there is an equally strong culture and sense of community within that consolidated district, which encompasses many towns, as there was within the local consolidated high school.”

Nevertheless, she added, “I think there are things about the identity of the local community that have really fluctuated and have been diminished somewhat by the loss of the school. Now, that’s exacerbated by the fact that a lot of people have moved into town who didn’t grow up here. The only experience they know is the consolidated district, and so they are immediately part of that culture and not part of the Atlanta identity and culture that sort of drove the community during that period of the centralized school.”[10]

- Catherine Maciariello, telephone interview with author, October 23, 2019; “Classrooms & Community,” companion exhibition accompanying Crossroads: Change in Rural America, Atlanta Museum, Atlanta, IL, February 2-March 16, 2019. ↵

- “Classrooms & Community,” Atlanta Museum. ↵

- “Classrooms & Community,” Atlanta Museum. ↵

- “Classrooms & Community,” Atlanta Museum. ↵

- “Classrooms & Community,” Atlanta Museum. ↵

- “Classrooms & Community,” Atlanta Museum. ↵

- Catherine Maciariello, telephone interview with author, October 23, 2019. ↵

- Mark Hallett, “IH ‘Forgotten Illinois 200’ Online Gallery Wins IAM Award,” Illinois Humanities, November 2019, https://www.ilhumanities.org/news/2019/11/ih-forgotten-illinois-200-online-gallery-wins-iam-award/. ↵

- Catherine Maciariello, telephone interview with author, October 23, 2019. ↵

- Catherine Maciariello, telephone interview with author, October 23, 2019. ↵