9 Assessing Learning

Introduction

In stage one of Backward Design, we identified learning goals that clearly and precisely defined what students would know, understand, and be able to do at the end of our instruction. But how will we know if we have achieved those outcomes? How will we know if our lessons “worked,” or if our students are “getting it”? Assessment, or finding ways to determine whether our students are learning what we intended them to learn, is a crucial part of instruction. Assessment involves developing activities that will allow our learners to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, and abilities and then analyzing those activities for evidence of how well students have achieved the learning outcomes.

No matter how carefully we plan a session, we cannot assume that by the end students have necessarily learned what we intended them to learn. Maybe some part of our lesson was unclear. Maybe we moved through some material too quickly or did not give learners enough time to absorb information and practice skills. By illuminating where students are learning, and where they are not, assessment “provides important feedback that librarians can use to improve their teaching” (Oakleaf & Kaske, 2009, p. 276). We can use assessment data to revise our instruction in order to better meet the goals, leading to both better teaching and better learning.

In addition to measuring achievement of outcomes, “assessments can be tools for learning, and students can learn by completing an assessment” (Oakleaf, 2009, p. 540). Because assessment activities typically require students to apply or reflect on knowledge and skills, Grassian and Kaplowitz (2001, p. 287) assert that a strong assessment activity “benefits the learner and helps to reinforce the material that was taught. Research has indicated that people who become aware of themselves as learners—that is, those who are self-reflective and analytic about their own learning process—become better learners.” Similarly, assessment encourages instructors to reflect on their practice and can lead to better teaching. As we review assessment data, think about what worked well and what did not, and make changes to our practice, our skill as instructors increases (Oakleaf, 2009). Ideally, instruction and assessment should be inseparable.

Assessment, Evaluation, and Grading

The words “assessment” and “evaluation” are often used interchangeably. Although they are related, the terms do not mean exactly the same thing. Assessment is a process of measuring progress toward learning outcomes with a focus on improving teaching and learning. Evaluation seeks to place a value on a service or program, often as part of determining whether to continue that service or program, or how best to allocate resources among programs and services. In their simplest terms, assessments are measures directly tied to learning outcomes, while evaluation focuses on learners’ satisfaction with or perceptions of the session. Evaluation of instruction is explored in more detail in Chapter 13.

Instructors associate assessment with grading but they are not the same, and we must be careful to differentiate the two. Outside of the K-12 school system, librarians are rarely in a position to assign grades, but that does not mean we should not care about assessment. Assessment simply means finding a way to determine if students have achieved the outcomes we set and, as such, is applicable to all instructors, regardless of whether they are assigning grades.

While assessment focuses on progress toward goals and seeks ways to improve learning, grades are used to make an overall determination of a learner’s performance. Grades often address areas such as attendance, effort, or conduct, which are not reflective of whether students learned what they were supposed to learn. For instance, a “B” grade could indicate that students’ work was satisfactory and they participated in class, but that grade might not reflect their ability to recall and apply knowledge and skills in new contexts.

Grades are usually assigned at the end of the learning process, giving an overall picture of student performance. Typical examples include grades on final exams or projects, or end-of-term grades. Assessment can, and should, take place at other points in the lesson, in addition to the end, thereby showing us if learners made progress over the course of the instruction. Overall, assessment is generally a better measure of learning than grades are, and more useful in making decisions for improving teaching and learning.

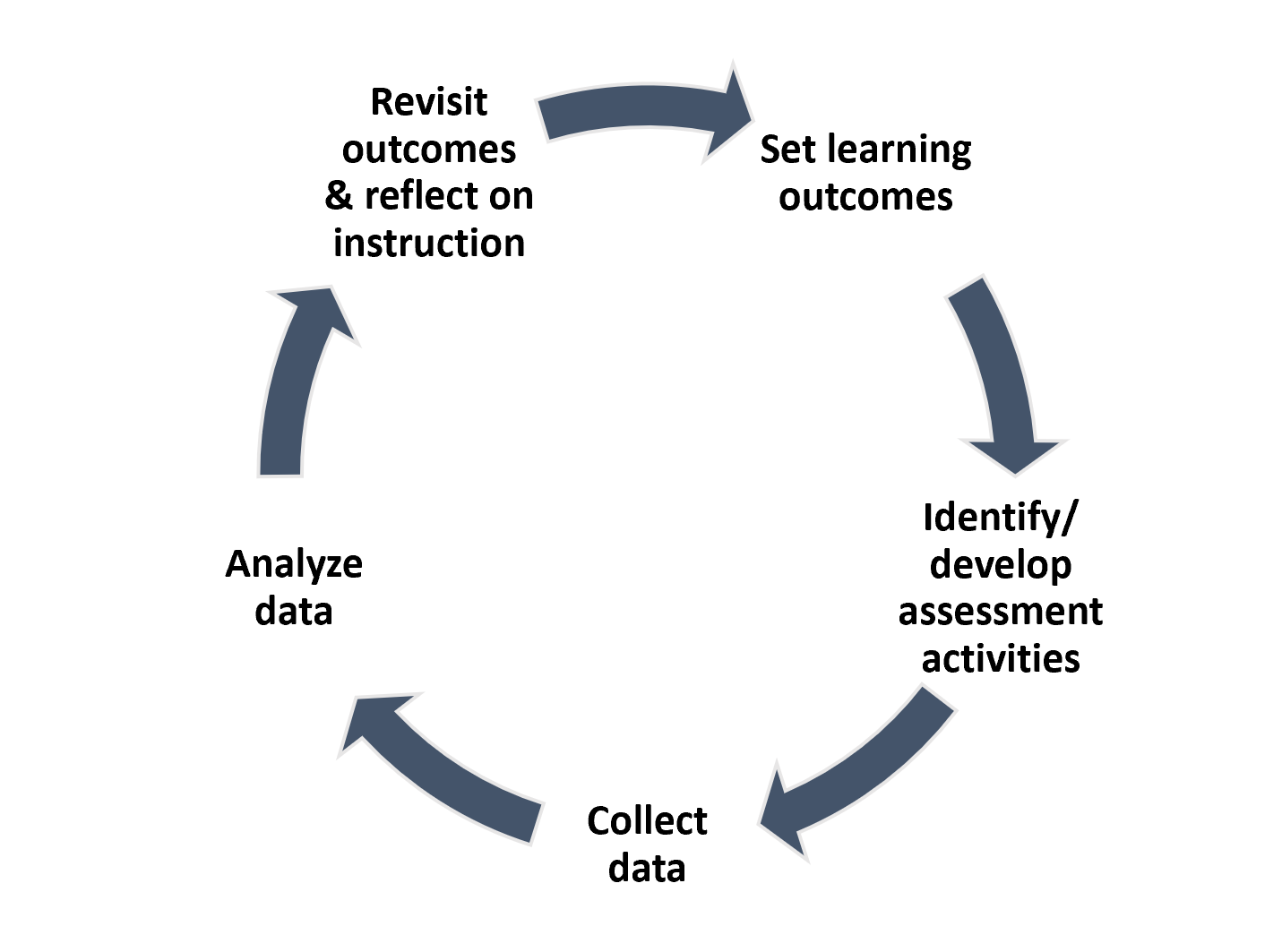

The Assessment Cycle

Assessment is meant to be iterative as we make incremental adjustments and keep improving our practice (Oakleaf, 2009; Oakleaf & Kaske, 2009). We can think of assessment as a cycle having five steps:

- Set learning outcomes. Setting learning outcomes is the first stage of Backward Design and is also the first step of the assessment cycle. These outcomes are the goals against which we will measure progress.

- Identify and/or develop assessment tools and activities. The second step of the assessment cycle, as with Backward Design, is to identify assessment measures. These measures are usually activities that allow learners to demonstrate and reflect on their knowledge, skills, and abilities. Often, we develop our own assessment tools, such as surveys, writing exercises, or worksheets, for assessment. Examples of assessment activities are provided later in this chapter.

- Collect data. The third step is to implement the assessment activities and collect the data they provide.

- Analyze data. Once we have assessment data, we need to analyze it by looking for evidence that learners are achieving the outcomes we set. In cases where students are not fully achieving outcomes, we should try to identify the gaps, misunderstandings, or challenges that are preventing achievement.

- Revisit outcomes and reflect on instruction. Assessment data should inform decision making. Once we know how well learners are meeting outcomes, we can revisit and, if necessary, revise those outcomes. If a large majority of students are consistently achieving an outcome, we might consider tweaking that outcome to make it slightly more challenging. On the other hand, if a large group of students is not meeting the outcome, we might revise the outcome to better align with our learners’ developmental stages and abilities, or review our teaching methods and instructional strategies to see if we could clarify concepts. Naturally, it is unlikely that all learners will successfully achieve all outcomes. In analyzing the data, we can look for patterns where students are consistently hitting roadblocks so we can address those. When we find outliers, or individuals and small groups that are not achieving outcomes, we can reach out to those learners directly to offer extra support. Figure 9.1 illustrates the cycle of assessment.

Figure 9.1: The Assessment Cycle

Types of Assessment

Assessment activities fall into several categories, including summative or formative, direct or indirect, and formal or informal. Each type of assessment serves a purpose, and each has its advantages and disadvantages. When selecting or designing assessment activities, we should consider what types of activities are most appropriate for our audience, content, and time frame.

Summative and Formative Assessment

Summative assessment comes at the end of a session or unit and gives a final overview of whether learners fully achieved the outcomes (you can think of it as “summing up” the session). Summative assessments can take many different forms, but some common examples are a final project, test, or presentation. Summative assessments provide us with a broad overview of student learning and the overall success of the lesson. Depending on their design, they can also give students an opportunity to synthesize the knowledge and skills they learned throughout the session, and to reflect on their learning. However, because summative assessments come at the end of the session, we generally will not have time to address any gaps, questions, or misunderstandings that the assessment reveals. We can use the information to improve our lesson for next time, but that will not benefit the current group of learners.

Formative assessment takes place during the session. Some people refer to formative assessments as “taking the temperature of the class” or as a “dipstick test” because they let us quickly check how students are doing, just as a dipstick can quickly check the level of oil in your car. The purpose of formative assessment is to diagnose issues during the course of the lesson so that you can make incremental adjustments as you go. For instance, during a lesson on plagiarism and citation styles, you might ask students to identify instances of plagiarism from a list of examples or give them a worksheet to format citation styles. As the students answer the questions, you will be able to see if they are understanding the lesson, and, if not, you can review or clarify as necessary.

Formative assessment gives us time to address issues before the session is over and learners move on. It can also ensure that students have mastered a certain concept or “chunk” of a lesson before we try to build on that knowledge or skill. However, by itself, formative assessment might not show us whether students fully achieved the learning goals for the session. Ideally, we should use both formative and summative assessments in our lessons.

Direct and Indirect Assessment

Assessment activities can be either direct or indirect. Direct assessments require students to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, and abilities, while indirect assessments ask students to self-report on their perceptions of what they learned. Direct assessments can include worksheets, tasks, or “performances” such as having students walk us through a search strategy or the evaluation of a resource and explain their reasoning. Indirect assessments are generally more reflective and involve self-assessment by the students. These assessments can include questionnaires or reflective papers that ask students to describe what they have learned, how well they feel they have achieved learning outcomes, or how confident they feel in their knowledge and skills. The important difference is that while students tell us that they have learned something through indirect assessment, they are not showing us what they have learned, and we cannot be certain that students are accurate in their reflections or self-perceptions.

Research suggests that people are not necessarily very good at assessing their own abilities (Brown et al., 2015; Ross, 2006) and that the people with less well-developed skills and knowledge are even more likely to overestimate their abilities (Campbell, 2018). Even though students’ assessments of their own abilities might not be accurate, indirect assessments are still useful tools because they give learners an opportunity to reflect on the lesson which might help them make new connections and recognize areas for improvement. Also, if instructors provide students with feedback on their self-assessments, they can help learners identify areas where their self-perception varies from what the instructor has observed, which can “lead to productive teacher-student conversations about student learning needs” (Ross, 2006, p. 9). After reviewing the literature on student self-assessments, Ross concluded that “there is persuasive evidence, across several grades and subjects, that self-assessment contributes to student learning” (2006, p. 9).

Formal and Informal Assessment

Formal assessments are usually planned in advance and intended to reach all students, and they typically result in hard data. Formal assessments could include worksheets, reflective papers or journals, projects, and quizzes. Informal assessments are usually just quick check-ins meant to give the instructor a sense that the class is on track. For instance, an instructor can take a quick poll of the classroom, pause and check for questions during a lecture, or observe learners engaged in hands-on practice. Academic librarians who have been invited into a classroom could also ask for informal feedback from the faculty member whose class they are visiting. Formal assessments will usually give us more information, but they are also generally more time-consuming. Informal assessments are less reliable, but they are usually quick and can be a good supplement to formal assessment.

Authentic Assessment

Assessments that provide students with opportunities to demonstrate their learning are sometimes called “authentic” assessments and are contrasted with “traditional” assessments. Traditional assessment refers to the closed-ended or forced-choice activities, such as tests, that require students only to select the correct answer form a fixed list of choices (Mueller, 2018). Fixed-choice tests can be reliable data-collection instruments, are quick and easy for instructors to score, and remain popular assessment tools. However, traditional assessments have been criticized because they focus solely on students’ recall of basic facts rather than higher-order thinking skills. Further, the highly controlled, timed environment in which tests are typically given is largely removed from the real-world environments in which learners would employ the knowledge and skills being tested (Oakleaf, 2008). A student could score well on a test but not be able to transfer that knowledge to other situations. To avoid these limitations, we should focus our efforts on authentic assessments whenever possible. Keep in mind that these examples are not mutually exclusive. We could create an assessment that combines both traditional, recall-based questions, along with more authentic activities. For instance, a worksheet could ask learners to list the Boolean operators (traditional), followed by a question asking them to use those operators to create a logical search string or telling us when and how they would use the operators in their own searching (authentic).

Developing Assessment Activities

The first step to developing or selecting assessment activities is to reflect on our learning outcomes. Some assessment tools and activities are better suited than others to certain learning outcomes, and each one will give us somewhat different information. For example, if one of our outcomes is for students to use Boolean operators to broaden and narrow searches, an activity that requires them to create search strings with Boolean operators will tell us more than a quiz that asks them to name the operators or identify which search strings will bring back more or fewer results. A short reflective paper asking learners when and why they would use Boolean operators can help us determine if they are ready to transfer the skills they have learned to other contexts. Our task is to decide exactly what we want to learn from our students and then select or create an activity that will allow us to gather that information.

The range of possible assessment activities is wide. This section provides a brief overview of a variety of assessment activities, with an emphasis on those most likely to be used for library instruction. Some of the activities listed here are duplicated in Chapter 4, but they are repeated here because many active learning techniques work equally well as assessments. Many more examples of assessment activities can be found online and in the Suggested Readings at the end of this chapter.

Worksheets

We can ask learners to complete worksheets with questions or tasks that require them to use the skills they have learned in class. We can ask almost any type of question on a worksheet, including closed-ended questions like multiple choice and true/false, fact-based questions with a single right answer, or short-answer questions that require learners to explain a concept or justify their reasoning. The specific questions should relate to the learning outcomes and session content and focus on what we want to know about our students’ learning.

Completed worksheets will show us how well individual students are performing, and, whenever possible, we should offer students feedback on what they did well and correct errors and misunderstandings. In addition to assessing individual learners, we can look at a set of worksheets as a whole for patterns. If several students perform poorly on a certain section or get the same question wrong, that can be a signal that we need to review that material and perhaps revise our instructional approach. Example 9.1 and Example 9.2 show two worksheets, one from an academic session for undergraduates beginning a research paper and one from a public library session on online security.

Example 9.1: Academic Library Instruction Session Worksheet

This worksheet is an example of an assessment activity for undergraduates beginning a research paper. According to the lesson plan, by the end of the session the students will be able to:

- Identify appropriate keywords relevant to their topic.

- Use Boolean operators appropriately to broaden and narrow searches.

- Find scholarly articles relevant to their topic.

Research Paper Worksheet

- Describe your topic in one sentence, or list your research question here:

- Select the main keywords from your topic, and brainstorm synonyms for each keyword.

- Using your keywords and synonyms, create two to three search strings you can use to search for articles on your topic. List your search strings here:

- Using your search strings in the Academic Search Complete database, find two or three scholarly articles that seem appropriate to use in your paper, and list their citations here:

- For each article, list two or three criteria that show it is a scholarly article.

Example 9.2: Public Library Instruction Session Worksheet

This worksheet example is from a public library workshop on creating an email account. According to the learning outcomes, by the end of this workshop learners should be able to:

- Create a strong password for their accounts.

- Discuss how their data is used online.

- Identify safer/secure browsing options.

Online Security Worksheet

- Name two things you can do to create a strong password.

- Which of the following is the strongest password, and why?

- Password1234

- Lunch@noon

- 10282000 (the date of your birthday or anniversary)

- KXjlm4pz.900my$?

- Many online services such as browsers and social media track your activities and gather your data. Name two things that these companies might do with your data.

- Which of the following internet browsers does NOT track your search activities?

- Chrome

- Safari

- Edge

- TOR

- Some web addresses begin with “https://” instead of “http://.” What does the “s” mean?

- It is a commercial website.

- The site is in high definition.

- It has faster download times.

- The information on the website is encrypted.

Tasks and Demonstrations

Worksheets are useful when learning can be explained clearly through written answers, but sometimes we can gain a better understanding of learning by having our students carry out a task or demonstrate a process. For instance, imagine a public library instruction session on using email in which the outcomes are for learners to be able to send and reply to messages and include attachments with their messages. Asking students to write out the steps to attach an image to an email would be burdensome. Instead, the instructor could have the learners send her a test email with an attachment so that she could see if they are successful or have them demonstrate the steps for her.

Pre- and Post-Tests

Chapter 7 describes pre-assessments, including pre-tests that can probe what learners already know about a topic before the start of a lesson. We can pair pre-tests with a post-test that asks identical or similar questions at the end of the lesson to gauge student learning. Instructors can review question by question to see if learners generally were able to answer questions correctly on the post-test that they did not answer correctly on the pre-test, and can look across sets of tests to see if students scored higher on the post-test. A number of librarians have used pre- and post-tests with varying success to show gains in learning from library instruction (Bryan & Karshmer, 2013; Sobel & Wolf, 2011; Walker & Pierce, 2014). Using the construction of a “test” can be problematic, as learners may not expect to take a test as part of library instruction and may find the experience stressful and off-putting. However, while this assessment approach uses the term “test,” the actual activity does not have to take the form of a graded test but could be presented as a low-stakes worksheet or questionnaire. Keep in mind that tests that focus on recall of facts are not considered authentic forms of assessment.

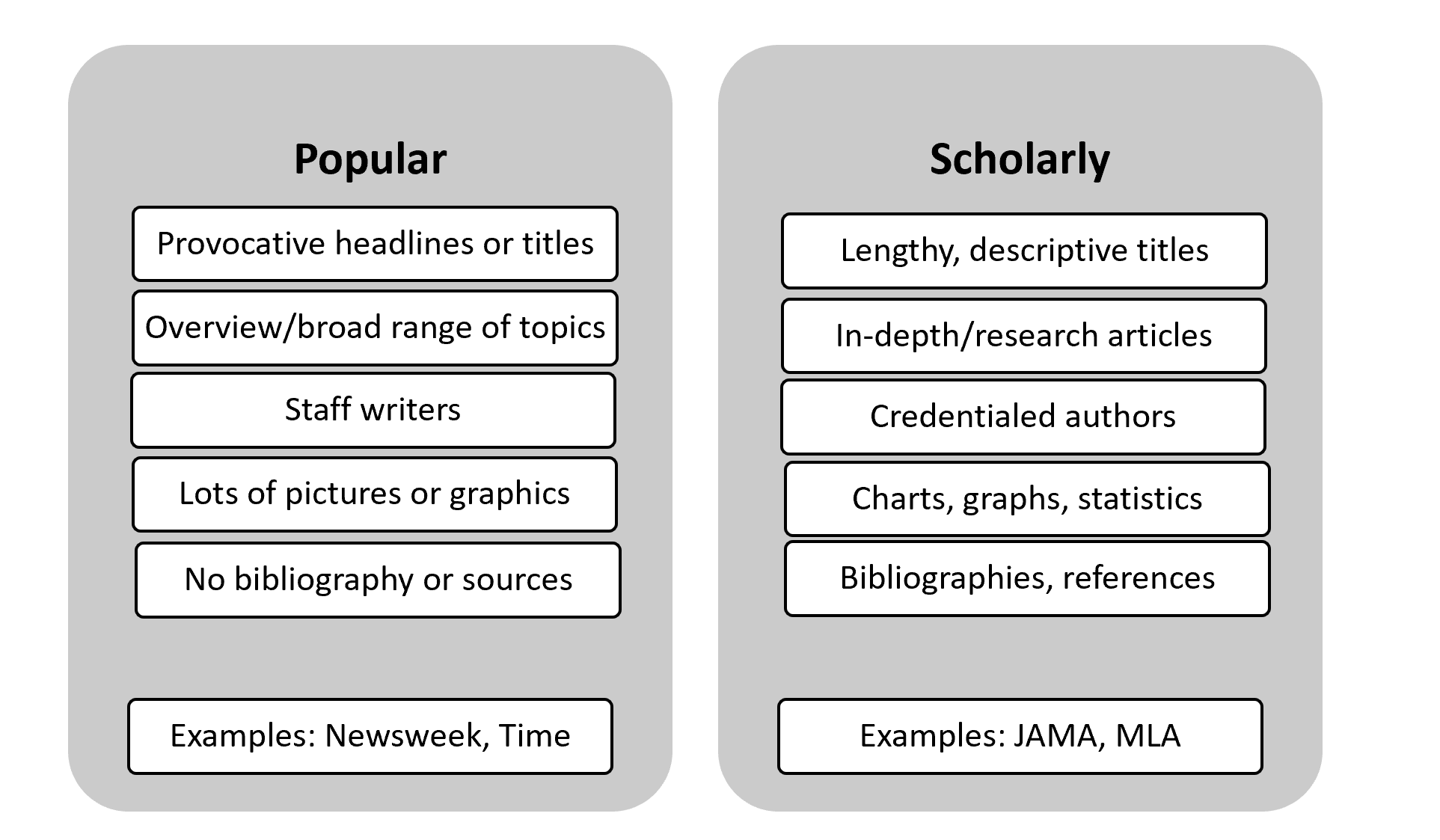

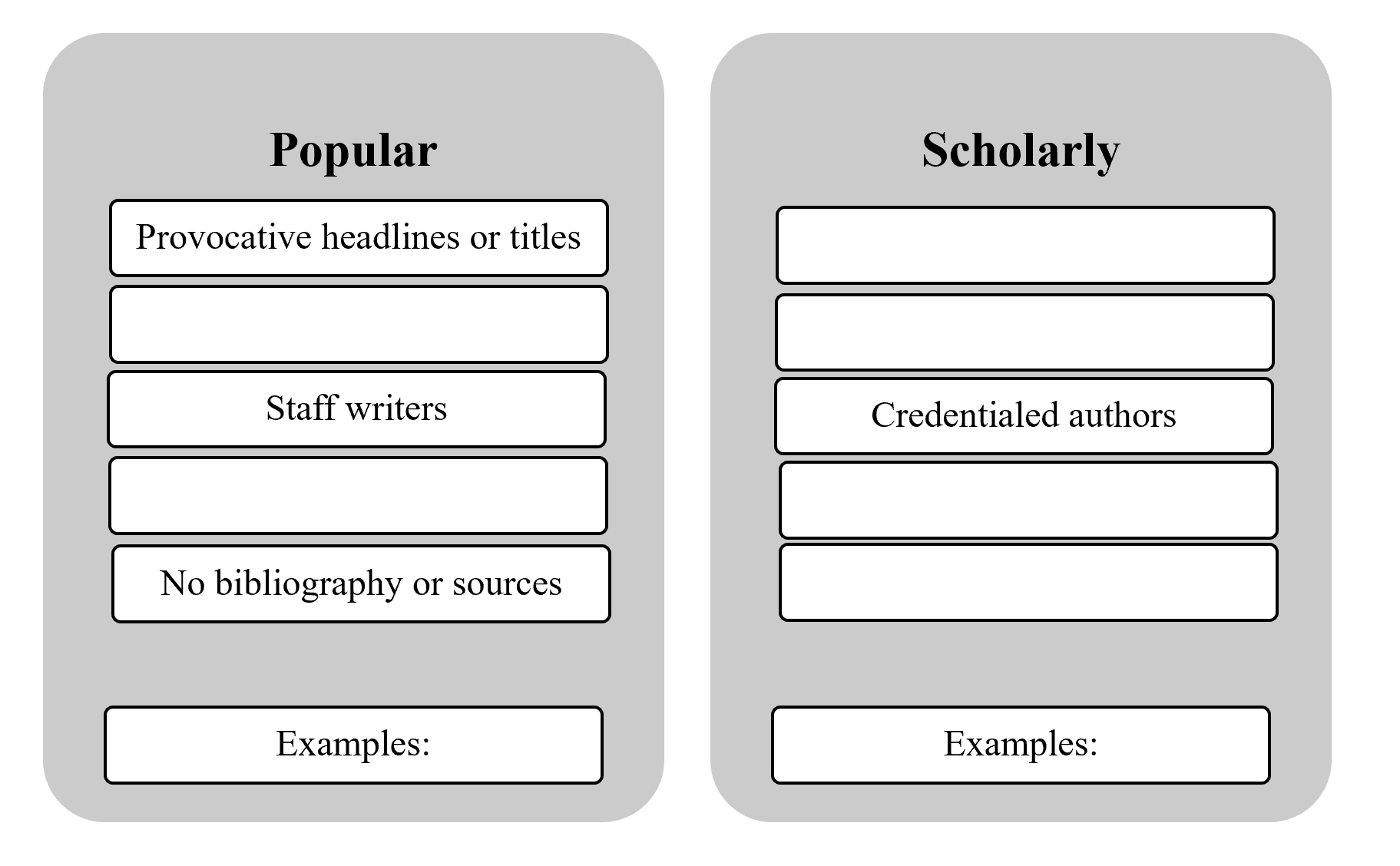

Graphic Representations

Infographics and other graphic representations of information are becoming increasingly popular in teaching, and they can be used as assessment tools as well. Instructors can provide learners with a partially completed graphic representation of a concept or process and ask them to fill in the missing information. A variety of graphic representations could work, including infographics, flowcharts, outlines, and grids. For example, you could use an infographic to outline the steps learners would use to fact-check a news story and assess its reliability. After reviewing each step and offering examples, you could give students a hard copy of the graphic with some parts missing and ask them to fill in the blanks. When using graphic organizers as assessments, you could provide learners with a list of the missing information so they need only put items in the appropriate place, or you could ask them to recall information from memory. See Figure 9.2 for an example and Activity 9.1 for a related exercise.

Figure 9.2: Assessment with Graphic Representations

Activity 9.1: Graphic Assessment

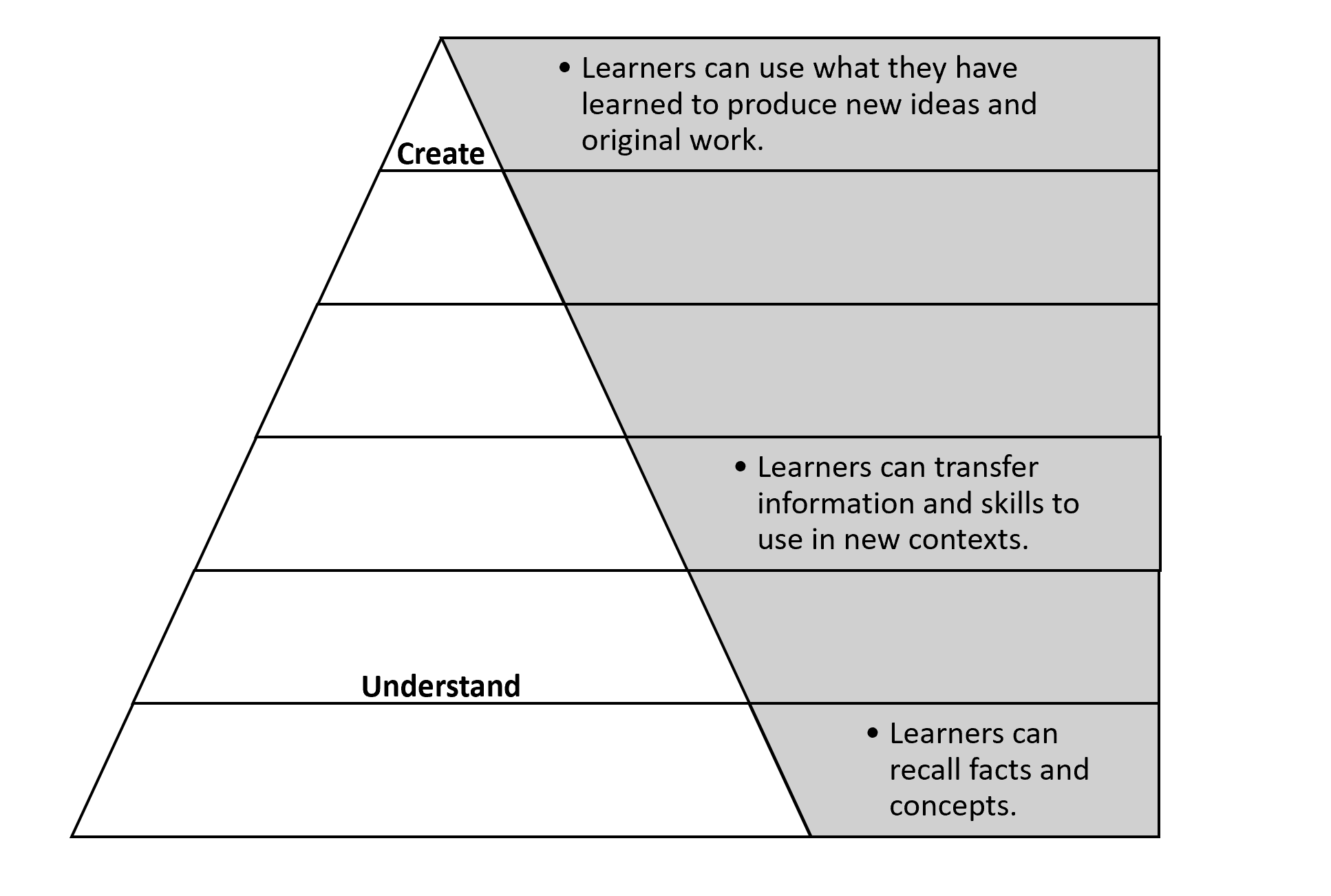

Your turn! In Chapter 8 you were introduced to Bloom’s Taxonomy, including a figure depicting the levels of learning. Figure 9.3 shows the same figure with some of the information missing. See if you can complete it without looking back; then check your answers.

Figure 9.3: Graphic Assessment for Bloom’s Taxonomy

Pro/Con Charts

Many library instruction sessions try to get learners to rethink their search behaviors. We often discuss the relative advantages and disadvantages of keyword versus subject searching, or of searching the general web as opposed to subscription databases for scholarly information. After such a session, we could assess students’ learning by asking them to fill out a chart listing the pros and cons of each of the methods discussed. For example, the ability to use natural language is an advantage of keyword searching, but the greater number of irrelevant results is a disadvantage. Subject searching is more precise, but it requires knowledge of a specialized vocabulary. To push students a little further, after reviewing the pros and cons we might ask learners to choose which method they would use and why. This follow-up question will show that they are not just recalling the advantages and disadvantages but that they understand how to apply the underlying concepts to make a good choice.

Annotated Bibliography

If our session focuses on skills related to evaluating and selecting trustworthy information, including identifying scholarly versus popular articles, assessing “fake news” and other general information, or finding appropriate articles for a research paper, we can have learners create an annotated bibliography to demonstrate their ability to evaluate sources and select quality information. We could give students time to search for their own materials or provide them with a list of resources to review, and ask them to select a certain number of sources that they believe are trustworthy and appropriate for their purpose. For each selection, students would write two to three sentences explaining why they selected that source, including how they evaluated it.

Short Writing Exercises

Brief writing exercises, of which many examples exist, give students an opportunity to reflect on and demonstrate learning. Exit tickets ask students to provide a brief answer to a question, summarize key points, or solve a problem related to the session outcomes and turn it in on their way out of class. Directed paraphrasing asks learners to explain a concept in their own words. Instructors will sometimes ask learners to “explain the idea to me as if I were five years old,” encouraging the learner to use clear and simple language. The learners’ ability to translate a new idea into their own words demonstrates a different level of understanding than simply reiterating a definition, and also suggests an ability to transfer the learning to new contexts. A similar exercise asks students to distill a lesson, idea, or concept into a one-sentence summary, showing not only their recall of the lesson but their ability to extract the most important ideas. An application card asks learners to write down one (or two or three) ways that they can use their new knowledge or skills. This exercise helps with transfer, as it encourages students to consider when and where they would use their knowledge and skills beyond the specific context in which it was learned.

Writing exercises can also be self-reflective. Instructors can ask students to describe one or two new things they learned, consider what questions they still have, or describe how their learning might change their behavior or strategies going forward. While these examples are all described as writing exercises, all of them can be done orally as well. Further, learners could discuss their answers in pairs or groups.

Selecting Assessment Activities

What factors should we consider when deciding which assessment activities to use? We want to choose activities that will be engaging and motivating for the learners. However, we should not choose an activity merely because it sounds fun. The first consideration should be to align the assessment with the session’s learning outcomes. Some assessment tools are better suited for knowledge and some for skills and processes. For instance, a writing exercise is appropriate if we want learners to explain how they would evaluate sources for a paper, but an activity or worksheet might be more appropriate if we want students to demonstrate how they would create search strings to find those sources. We also need to consider what aspects of learning we are most interested in assessing. Do we want to see if students remember information or whether they can apply it? Are we more interested in whether learners can perform a task or whether they know when and why to perform it? For example, in a plagiarism lesson, we could ask students to create a citation for an article or list three situations when a citation is needed. Both of these activities could tell us something about what students learned about citation, but only the former would be an assessment of the outcome “students will be able to create citations using APA style.” These goals are not mutually exclusive. We can create assessments that combine approaches, such as a worksheet that asks learners to format a citation and explain when to use citations. We just have to remember that different assessment activities produce different data and answer different questions.

While gathering the best and most appropriate data to measure learning is the most important factor in choosing an assessment activity, we should also consider our audience and logistics such as materials and time frame. For instance, complicated writing exercises might not be appropriate for younger students, English-language learners, or learners with certain disabilities. A short quiz might be fine for students in a school setting but off-putting to adults attending a workshop at a public library. If the activity is computer-based, such as submitting a web form, we need to be sure that all learners have access to an appropriate device for completing the task. Finally, some activities take more time than others, so we need to consider our time constraints. We probably do not want to plan an assessment activity that will take 15 or 20 minutes out of a 45-minute, one-shot session. See Activity 9.2 for an exercise on creating assessment activities.

Activity 9.2: Creating Assessment Activities

Listed below are sample learning outcomes related to library instruction across various settings. Choose one of these examples and create two activities that you could use to assess student learning for the outcome in your scenario. Try to create one formative and one summative assessment. You can draw from examples in this chapter or search the web for other ideas. Keywords like “classroom assessment,” “learning assessment,” and “assessment techniques” will bring back many results.

- Scenario 1: By the end of a library instruction session for first-year college students, learners should be able to identify and select appropriate articles for a research paper.

- Scenario 2: By the end of a public library session for older adults, learners should be able to search for and download selected titles on Overdrive.

- Scenario 3: By the end of a high school library instruction session, students should be able to identify passages that need citations and cite sources using MLA format.

- Scenario 4: By the end of a public library session on “fake news,” learners should be able to discuss criteria for identifying and evaluating mis- and disinformation.

- Scenario 5: By the end of a session at an academic archive, history students should be able to identify primary and secondary sources and use a finding aid to locate documents on their topic.

- Scenario 6: By the end of a session at a law library, staff should be able to customize their Westlaw interface to highlight preferred resources and use the KeyCite feature to check current status of cases and statutes.

Using Rubrics for Assessment

Assessing learning outcomes can seem ambiguous at times. Think about some of the assessment activities just discussed. The graphic organizer and some of the worksheet questions have clear right answers, so instructors would not find it hard to analyze those activities and decide if learners supplied the correct responses. In fact, provided with an answer key, a person unfamiliar with the lesson could complete the analysis. But other activities are not as clear. Entries in an annotated bibliography are less likely to be completely right or wrong, although some answers might be better than others. But what criteria, exactly, make a better or worse answer? Is a current review of a scientific breakthrough in a popular magazine better than a decades-old journal article on the same topic? Ambiguities like these can be frustrating for both students and instructors. Worse, they can lead to discrepancies in how student learning is assessed, since one instructor might judge the same student work differently from another instructor. The use of rubrics for assessment or “scoring” of student work can help minimize ambiguities and frustrations.

What Are Rubrics?

Rubrics are tools that describe different levels of performance for an activity, task, or assignment, and these descriptions can guide our assessment of student performance. People might use different labels to describe points along the continuum, but commonly, rubrics describe novice, intermediate, and advanced levels of performance. We can use swimming as an example: a novice swimmer might just be able to stay afloat doing the doggie paddle, while an intermediate swimmer can do the crawl, and an expert swimmer can do the breaststroke. To use a library instruction-related example, a novice searcher might use simple keyword searches, while an intermediate searcher can use Boolean operators and quotation marks correctly, and an expert searcher can nest terms and use truncation as well. Example 9.3 gives a simple example of a rubric on plagiarism. As the sample rubric illustrates, rubrics detail successful performances by identifying the various criteria used to judge the knowledge, understanding, and abilities we are examining, and then describing levels of performance for each criterion. Rubrics tell us (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, p. 173):

- By what criteria we should judge performance.

- Where we should look and what we should look for to judge performance success.

- How the different levels of quality, proficiency, or understanding can be described and distinguished from one another.

Example 9.3: Plagiarism Rubric

| Criterion | Novice | Intermediate | Advanced |

| Topical knowledge | Can identify a definition of plagiarism | Can explain plagiarism in own words | Can explain plagiarism in own words and provide examples |

| Application | Cannot identify instances of plagiarism from examples

Cannot identify passages that require citations |

Identifies some instances of plagiarism from examples

Identifies some passages that require citations |

Consistently identifies instances of plagiarism from examples

Consistently identifies passages that require citations |

| Execution | Does not format citations properly | Formats most citations properly | Consistently formats citations properly |

Why Use Rubrics?

Rubrics offer many advantages for both instructors and learners (Oakleaf, 2008). Perhaps most importantly, rubrics reduce ambiguity by defining what successful performance looks like. Too often instructors do not take the time to describe in detail what constitutes an expert performance or an “A” paper. When asked, these instructors often demur and say that “they know it when they see it.” While seasoned instructors probably do know intuitively what makes a good performance or paper, if they do not describe it, others, including students, cannot be sure they understand what is necessary to be successful. By defining measures of quality and proficiency, rubrics act as guides for both students and instructors.

Rubrics give learners “the rules for how their products and performances will be judged,” and, as such, empower students to meet the standards (Oakleaf, 2008, p. 245). These levels of performance might seem especially important when students are receiving grades, but even in one-shot sessions and workshops or for ungraded assignments, rubrics can facilitate learning and self-assessment. Once students understand the criteria and standards in rubrics, they can use them to reflect on their learning and engage in an honest assessment of their own work (Oakleaf, 2008).

For instructors, rubrics encourage reflection and promote standardization. Defining the criteria and describing the levels of performance force instructors to be clear with themselves, and, ultimately, their students and colleagues, about what aspects of the learning really matter. Using the rubric as a guide, instructors can be more consistent in how they assess each piece of student work. In fact, if rubrics are clear and detailed, they “come close to assuring that inadequate, satisfactory, and excellent mean the same thing on the same skill set from one group of students to a similar group regardless of who makes the evaluation” (Callison, 2000, p. 35). In this way, rubrics help standardize assessment and make the process less ambiguous and arbitrary.

Developing Rubrics

Rubrics are often laid out as tables or grids. The columns of the table identify the various levels of proficiency, while the rows identify the criteria by which the performance is assessed. The first step to developing a rubric is to identify the criteria by which we will evaluate performance. What knowledge or understandings should learners have? What skills should they be able to demonstrate? What should we look for in their performances, activities, or assignments that would illustrate the required knowledge, understanding, or skills? Criteria for assessment could relate to Bloom’s Taxonomy, with sections for basic knowledge, application of knowledge, and analysis. We might also focus on steps in a process or task, or evidence of critical thinking. Depending on the assignment and related learning outcomes, written skills or public speaking and presentation skills might be important. One area to generally avoid in rubrics is effort, as it is usually difficult to infer how much effort went into an activity, and effort is rarely related to the learning outcomes.

We can see examples of criteria in the first column of the rubric in Example 9.3. In order to avoid plagiarism, learners must know what plagiarism is and know when and how to cite their sources. Thus, the criteria for evaluating student understanding of plagiarism are topical knowledge (defining plagiarism), application (knowing when to cite sources), and execution (accurately formatting citations). These criteria head the rows of the table.

Once we have the criteria, we can describe the levels of performance. In theory, we can define as many levels of performance as we want, but most instructors limit themselves to three or four levels. Describing the levels of performance in clear and precise terms is both important and often rather challenging. We must provide enough detail that learners can understand the expectations for performance, while leaving some flexibility to accommodate the range of work we are likely to see. One pitfall that novice instructors often make is quantifying criteria. For instance, we might be tempted to separate novice, intermediate, and advanced research papers by the number of scholarly references they include. However, a rubric that indicates a paper with, say, three scholarly references is a novice while one with five is advanced can be overly restrictive and puts the emphasis on quantity over quality. After all, are we more concerned with how many articles students can find, or whether they are selecting articles that are appropriate to their assignment and topic? Since we are probably more concerned with the latter, we should relay that in our delineation of the criteria. Rather than focusing on numbers of articles, we might assess the learners by the types of articles they are citing. Have they found articles that are relevant, timely, and appropriately scholarly?

Vague or ambiguous descriptions are another common pitfall in rubrics. Instructors often have a hard time articulating what distinguishes the different levels of performance and, as a result, default to words like “many,” “some,” “often,” or “sometimes.” For example, an instructor might say that a novice searcher rarely uses Boolean operators, while an intermediate searcher sometimes uses them, and an advanced searcher often does. But what is the difference between rarely, sometimes, and often? If a searcher uses Boolean operators 25 percent of the time, would that be considered novice or intermediate? Avoiding such language is challenging, but we should strive to make our descriptions as precise as possible. See Activity 9.3 for an exercise on developing rubrics.

Activity 9.3: Creating Rubrics

In Activity 9.2 you were given several scenarios of library-related learning outcomes, and you developed two assessment activities to measure one of those outcomes. Review the outcome and assessment activities from that section, and then design a rubric that you could use to assess student performance on one of your activities.

As you create your rubric, consider the following:

- What would a “quality” or “successful” performance of that activity look like?

- What criteria could you use to judge or assess that performance? Try to identify two or three criteria relevant to your outcome and activity.

- What aspects of the performance or activity should you focus on as you assess?

- How would you distinguish different levels of quality or proficiency for this outcome? Try to describe three levels of performance for each criterion.

Providing Feedback

Remember that assessment is not just for the instructor. Students can also benefit from assessments by learning what they are doing well and where there are gaps in their knowledge, skills, or abilities. While students might reflect on their learning and recognize areas for improvement simply by engaging in the assessment, instructor feedback is important for ensuring that students continue to learn and make progress. Whenever feasible, we should provide learners with feedback on their performance on any assessment activity. Feedback should be both positive and constructive. We should tell students what they did well, in addition to identifying areas for improvement. When we do identify gaps, errors, or misconceptions, we should focus on how to improve. For instance, if students choose a problematic resource for a research paper, we should help them understand why that resource is not appropriate, and help them figure out how to make a better choice by discussing appropriate outlets to search and by reviewing the criteria for evaluation.

Rubrics can also be used for feedback. Many instructors will return a copy of the rubric with an assignment or feedback sheet and highlight the learners’ performance along the continuum. Because rubrics already outline performance expectations, instructors can sometimes point to the language on the rubric rather than rewriting comments, thus streamlining the feedback process. Some instructors will add blank columns to the rubric where they can write additional comments to elaborate on the assessment.

This personalized and detailed feedback can be difficult to implement in a one-shot session or workshop where we typically do not have sustained contact with the learners after the class ends. Some librarians develop worksheets as web forms or have learners email their activities so that they can provide feedback after class. In school and academic libraries, we can ask students to write their names on worksheets and writing exercises, and then return the worksheets with feedback via the regular classroom teacher. If individual feedback is not possible, we can offer broad, generalized feedback to the group. For instance, we can circulate as students engage in in-class activities and then address common mistakes or issues that we observed, or we can distribute an answer key of correct answers for learners to review after class.

Conclusion

Assessment is a crucial step in instructional design that can lead to improved teaching and increased learning. Developing a well-designed assessment tool that provides us with accurate evidence of student learning takes time, but the benefits to both students and instructor make that time a worthwhile investment.

The key points of assessment include:

- Assessment activities gather evidence of progress toward learning outcomes. Using the data from assessment activities, we can determine where gaps in learning exist and tweak our lessons to address these gaps, leading to improved instruction.

- Assessment also leads to improved learning in several ways. First, as we adjust our instruction based on assessment data, we can ensure students continue to learn and make progress. Also, students can learn from the assessment activities themselves.

- A variety of assessment activities exist. In selecting assessments, we should look for activities that align closely with the stated learning outcomes of the lesson. We should also be sure that the activities are appropriate for our audience and time frame.

- Feedback helps learners recognize what they are doing well and where they can improve. We should strive to give feedback that is both positive and constructive, and that offers guidance not just on where to improve but how to improve.

- Rubrics are a useful assessment tool that can reduce ambiguity, increase consistency of assessment, and streamline feedback.

Suggested Readings

ACRL Framework for Information Literacy Sandbox. (n.d.). https://sandbox.acrl.org/resources

The Association of College & Research Libraries has compiled this open-access collection of instructional materials focused on The Framework for Information Literacy. Users can search for assessment materials and rubrics on a variety of information-literacy topics. Many of the classroom activities could also function as assessment tools. All materials are licensed through Creative Commons and can be reused and adapted with limited restrictions. All of the materials are designed for a college audience, but many could be adapted for other audiences.

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques. Jossey-Bass.

This classic handbook offers myriad examples of classroom assessment techniques, with concrete advice on how to implement them. The book begins with an introduction to classroom assessment and offers clear guidance on how to integrate assessment into your practice. Although the text was written for higher education instructors, many of the techniques could be adapted to a younger or more general adult audience. A selection of 50 activities from this book is available freely online from the University of San Diego (https://vcsa.ucsd.edu/_files/assessment/resources/50_cats.pdf)

Arcuria, P., & Chaaban, M. (2019, February 8). Best practices for designing effective rubrics. Teach Online. https://teachonline.asu.edu/2019/02/best-practices-for-designing-effective-rubrics/

This brief article offers a clear and concise definition of rubrics, plus a useful guide to creating and using your own rubrics.

Bowles-Terry, M., & Kvenild, C. (2015). Classroom assessment techniques for librarians. ACRL.

This book is a wealth of examples and ideas for a range of assessment activities, tailored specifically for the library classroom. An appendix addresses the use of rubrics and how to create them.

Dobbs, A. W. (2017). The library assessment cookbook. Association of College & Research Libraries.

Although not exclusively focused on instruction, this text compiles a wealth of assessment activities and examples, many of which are targeted to or could be adapted for instruction. Each assessment is presented as a recipe of one to three pages and includes reasons for using the assessment, links to professional standards and frameworks, an overview of how to implement the activity, and suggestions for adapting the activity to different settings.

McCain, L. F., & Dineed, R. (2018). Toward a critical-inclusive assessment practice for library instruction. Litwin Press.

This slim volume provides advice and strategy for assessing library teaching and learning through the lens of critical pedagogy, critical information literacy, and inclusive teaching. The authors provide an overview of critical practice and critical-inclusive assessment, along with examples of assessment in action in real classrooms. Although geared toward librarians teaching credit-bearing courses, many of the strategies could be adapted for other venues.

University of Iowa Libraries. (2018). Library instruction assessment toolkit. https://guides.lib.uiowa.edu/assessment

This LibGuide offers a selection of sample assessment and evaluation tools that can be downloaded and adapted, including minute papers, worksheets, and guidelines for peer review. Additional guides offer advice on providing written feedback and constructive criticism as part of assessment.

References

Brown, G. T. L., Andrade, H. L., & Chen, F. (2015). Accuracy in student self-assessment: directions and caution for research. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy, & Practice, 22(4), 444-457. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.996523

Bryan, J. E., & Karshmer, E. (2013). Assessment in the one-shot session: Using pre- and post-tests to measure innovative instructional strategies among first-year students. College & Research Libraries, 74(6), 574-586. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl12-369

Callison, D. (2000). Rubrics. School Library Media Activities Monthly, 17(2), 34-6.

Campbell, J. (2018). Dunning-Kruger effect. Salem Press Encyclopedia. EBSCO.

Grassian, E., & Kaplowitz, J. (2001). Information literacy instruction: Theory and practice. Neal-Schuman.

Mueller, J. (2018). Authentic assessment toolbox. North Central College. http://jfmueller.faculty.noctrl.edu/toolbox/whatisit.htm

Oakleaf, M. (2008). Dangers and opportunities: A conceptual map of information literacy assessment approaches. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 8(3), 233-253. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0011

Oakleaf, M. (2009). The information literacy assessment cycle: A guide for increasing student learning and improving librarian instructional skills. The Journal of Documentation, 65(4), 539-560. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410910970249

Oakleaf, M., & Kaske, N. (2009). Guiding questions for assessing information literacy in higher education. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 9(2), 273-286.

Room 241 Team. (2013, January 30). Grading vs. assessment: What’s the difference? Concordia University. https://education.cu-portland.edu/blog/classroom-resources/grading-vs-assessment-whats-the-difference/

Ross, J. A. (2006). The reliability, validity, and utility of self-assessment. Practical Assessment: Research & Evaluation, 11(10). https://doi.org/10.7275/9wph-vv65

Sobel, K., & Wolf, K. (2011). Updating your tool belt: Redesigning assessments of learning in the library. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 50(3), 245-258.

Walker, K. W., & Pierce, M. (2014). Student engagement in one-shot library instruction. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(3/4), 281-290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.04.004

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. ASCD.